Des huguenots en Provence orientale (1558-1594)

Abstract

If the involvement of higher nobles (the Guise, Bourbon, Montmorency, Coligny and Condé) in the religious wars is told in history books, the part played by the lower nobles is less well known ; and historians largely ignore the great lords of eastern Provence who joined the Reformation. Among the latter, in south-eastern France, and notably among those who owned manorial estates in what is now Alpes-Maritimes, Var and Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, one finds members of the Castellane, Oraison, Grasse, Grimaldi de Beuil, and Villeneuve families ; they are the topic of this study. Is early as 1550, bishopics were weakened by simony, money issues, and the trials for maintaining their temporal rights. The abbey de Lérins whose influence declined due to really poor management when it was held in commendam, became a Calvinist hotbed. Monks were driven out. Some bishops renounced their faith publicly, others became more or less openly Huguenot sympathisers. But the Reformation movement really took root within the noble class only from 1559 onwards, with the return of barons to their estates at the end of the Italian wars. Some had been in touch with German Lutherans and returned as converts of the “new faith”. Protected by the Governor of Provence, Claude de Tende, the Grasse, Lascaris and Villeneuve families prevailed upon their kin, local squires and notables to found small communities in which pastors from Geneva were welcome. Parties were created, which jeopardized the legendary aristocratic solidarity. Guerrilla warfare put the whole country to fire and the sword. In 1569, Claude de Villeneuve (the Lord of Vence), his brother Honoré de Villeneuve-Tourrettes-lès-Vence, and his uncle Jean de Villeneuve-Thorenc bought estates (and their associated rights) put up for auction by Bishop Louis Grimaldi de Beuil to pay for the tax increases imposed by the king so he could wage his religious wars. It seems that their ulterior motive was to rebuild their fiefdom, which, through an alliance with the Grasse and the Villeneuve-les-Fayence families, would have constituted a huge Protestant area. During the war that took place specifically in Provence between the Carcistes (the Catholic supporters of the Count of Carcès) and the Razats (Protestants who supported the Count of Retz), they made Saint-Martin-la-Pelote, Saint-Laurent-la-Bastide, and especially le Canadel into strongholds where their coreligionists and their troops could be accommodated. These wars took a heavy toll among local lords. Many died on the battlefield, others were ruined and were not able to pay for a Reformed minister anymore. When in 1589 Henri IV became King of France, many barons rallied round him to obtain royal pardon. As they no longer had any support, abjurations began. The end of religious wars in southeast Provence also marked that of the Provençal spirit of patriotism and that of political and military feudalism, while Tridentine bishops tried to recover the estates sold to the Villeneuve by their predecessors. Nevertheless, part of the population had embraced the Reformation. In the seventeenth century, the bishops from the dioceses of Vence and Grasse, during their visitations, made a point of identifying Protestants and of making priests and curates put the precepts of the Counter Reformation into practice.

How to Cite

More Citation Formats

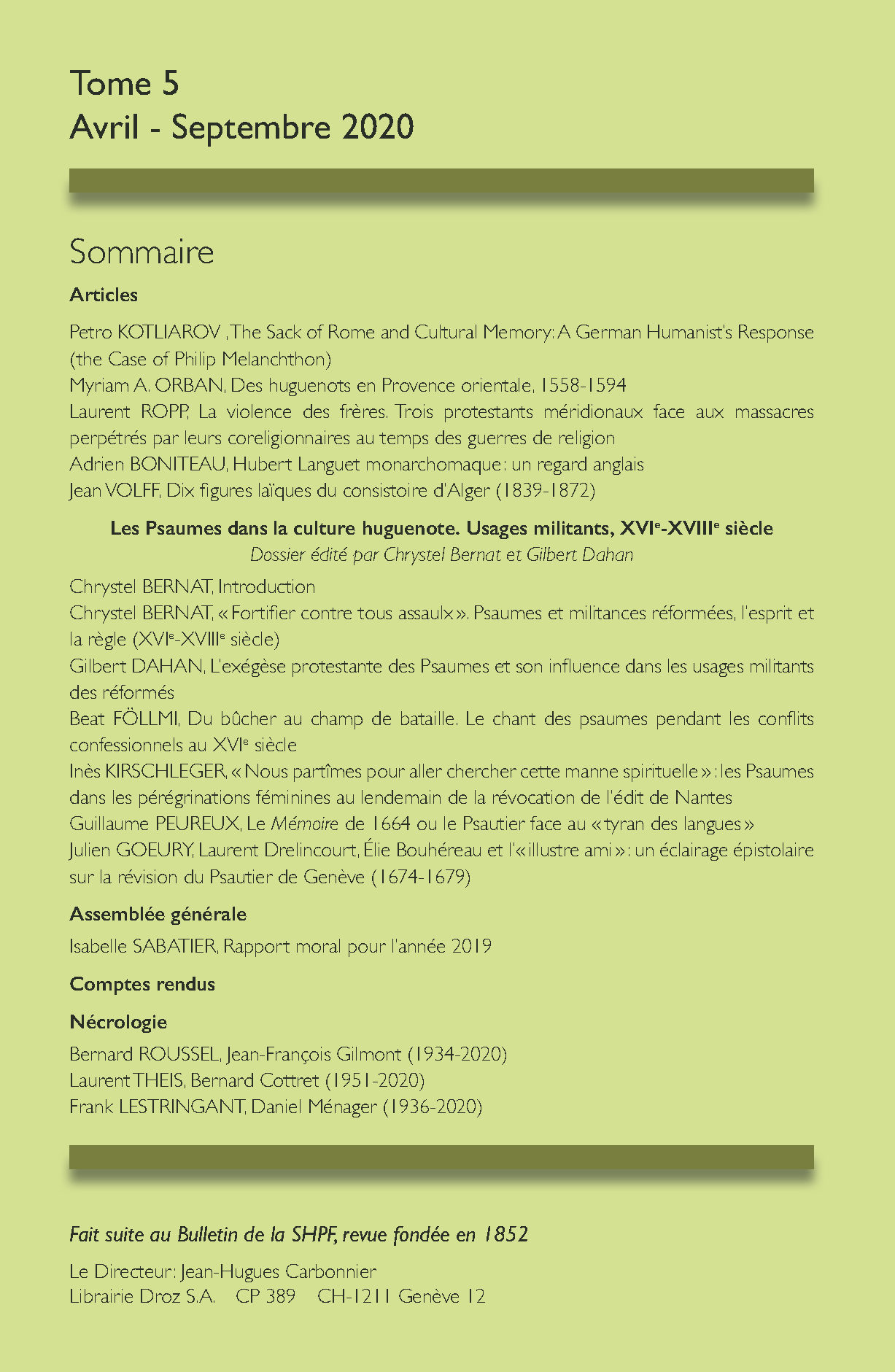

Issue