Tipografi- librai alle origini della Riforma in Italia

Abstract

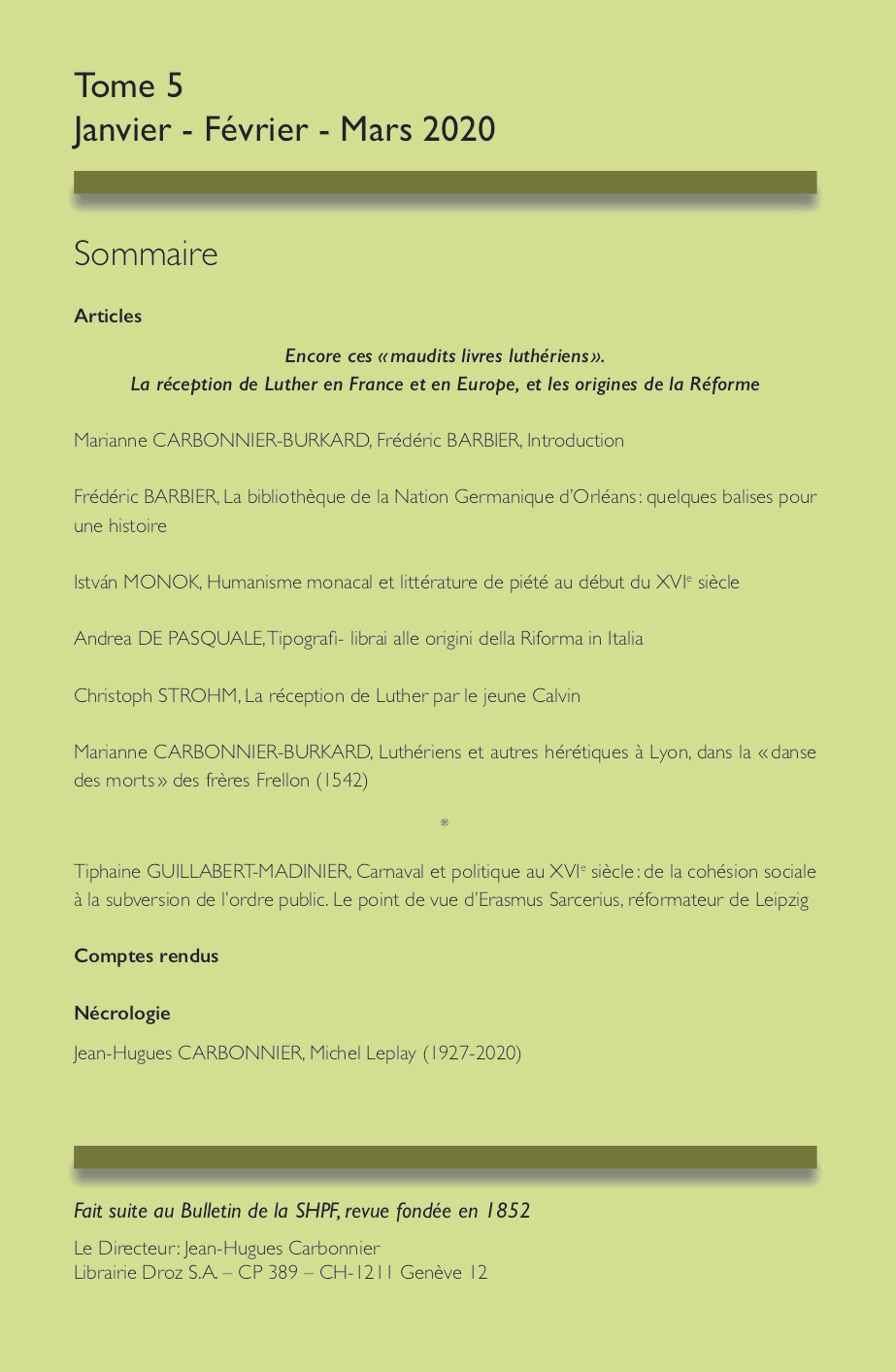

On 14 February 1519, the Basel publisher and printer Johann Fröben sent Martin Luther an update on the dissemination of editions of his printed works in Basel, and on the success of the Reformation in Europe. Noting developments in France, Spain, and England, Fröben also described the situation in Italy, in the course of which he mentioned a certain bookseller he calls Calvus. According to Fröben, this Calvus was active in Pavia, and certainly also in Milan, and often traveled beyond the Alps, especially in Basel and Nuremberg, attended trade fairs and was in contact with German booksellers, and was a proponent of the Reformation to the point of importing Lutheran works into Italy. Critics have generally identified this Calvus as Francesco Calvi, a bookseller in Pavia and Milan, active in the trade of Latin codices, which prompted him to make various trips throughout Europe, and brought him into contact with Erasmus and with the leading intellectuals and transalpine humanists of the time. Among them numbered Amerbach, Beatus Renanus, and Fröben himself, all largely sympathetic to Lutheran ideas. However, there are no concrete elements that lead one to believe that Francesco Calvo, also known by the epithet Minitius or Minucius (Minicio), was a Lutheran activist. There are no known complaints against him, and, on the contrary, it would seem that he opposed the Reformed ideas, as he edited the anti-Lutheran work entitled Oratio in Martinum Lutherum by Luigi Marliani. Moreover, he had moved to Rome as early as 1520, which evidently suggests that he entertained no doubts with respect to Catholic doctrine. The fact of the matter is that there was at that time not just one bookseller with the surname Calvus, but two, as Francesco had a brother named Andrea, like him a bookseller in Milan and in Pavia, as well as a publisher, who similarly entertained close contacts with intellectuals from across the Alps, in particular the Swiss territories and Lombardy, and was sympathetic to the Reformation. Indeed, when one examines Andrea’s his life, it becomes clear that he must be the Calvus of whom Fröben was speaking. When the Duke of Milan, Francesco II Sforza, on 23 March 1523 issued a first announcement against the owners of Reformed books, Andrea was even forced to abandon the city and to settle on the other side of the Alps, maintaining his profession as a bookseller. He returned to Milan in 1530, resumed the bookseller trade, but then his Lutheran ideas resurfaced, and in 1538, following new Milanese rumours, he was once again accused of trading in heretical books and ordered to appear before the Inquisition of Milan. It was not until 1541 that he wrote a plea admitting his mistakes, and recognizing that he had not divulged that his bookseller in Pavia was selling heretical books. He proclaimed himself a Catholic, and obtained grace. In any case, it seems certain that at the origin of the spread of the Reformation in Italy, there were booksellers who, for reasons of conviction and above all for trade, imported Protestant works printed across the Alps, even before Zoppino printed the first Italian edition of a catechetical text from Luther in 1525 in Venice.

How to Cite

More Citation Formats

Issue

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Andrea De Pasquale, La formazione della Regia Biblioteca di Parma, Histoire et civilisation du livre: Vol. 5 (2009): Une capitale internationale du livre: Paris, XVIIe-XXe siècles

- Andrea De Pasquale, Gloire à Gutenberg, Histoire et civilisation du livre: Vol. 11 (2015): Strasbourg, le livre et l’Europe, XVe-XXIe siècle

- Andrea de Pasquale, Des musées dans les bibliothèques : le cas des bibliothèques d’État en Italie, XIXe-XXe siècle, Histoire et civilisation du livre: Vol. 10 (2014): Où en est l’histoire des bibliothèques ?