The archaeological survey of the Valley of the Muses and its significance for Boeotian History

In the 1980’s the Bradford-Cambridge Boeotia Project (Bintliff, 1991; Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1985; Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1988a; Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1988b), extended its intensive archaeological field survey programme within the chora of ancient Thespiae city and that of Haliartos into the Valley of the Muses (Figure 1). As is probably known to all participants, our total field by field surface survey relied on the counting of surface densities of ceramics to separate «occupation sites» and cemeteries from offsite pottery — here very numerous — which represents intensive manuring in antiquity (Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1988c).

When I composed my abstract in the spring of 1994, I stated that the Valley of the Muses is virtually empty of people for much of the year, being farmed extensively in olives and cereals together with — chiefly at its eastern end — vineyards, from the modem villages of Panayia/Askra and Neochori which are situated on the outer hilly rim at the entry to the enclosed basin. However, as my friend Friedrich Sauerwein has pointed out in his study (Sauerwein, 1991) of demographic change in Boeotia since 1879, Boeotian agriculture and population have shown a sequence of unpredictable changes in focus and location over the last 100-150 years. I was made very aware of this during that summer whilst revisiting a number of our archaeological sites in the Valley of the Muses, since it was clear that commercial irrigation farming has begun to spread into the Valley, bringing with it far more human activity even in high summer. This should not suprise us, as the photographs taken by the French School in the 1880’s-90s showing the landscape around Thespiae and the Sanctuary of the Muses bear witness to yet another land-use: a virtually treeless one dominated by cereal and fallow fields and open hill grazing for large flocks of sheep and goat.

Nonetheless, at the time of carrying out our survey of the Valley of the Muses in the early to mid 1980s, there was a remarkable contrast between the absence of any contemporary settlement and the rarity of cultivators met with in the extensive interior of that basin, and the extraordinary number of archaeological sites which fieldwalking produced.

Previous to the survey, traditional knowledge of the Valley had focussed on the Sanctuary itself in the inner and upper recesses, just below the limit of cultivation, and the two notable landmark towers of Pyrgaki summit (Fourth Century BC) and the less dominating but equally extreme hilltop location of the Frankish tower (our site VM4) (Figure 2). In the vicinity of these towers was presumed to lie the only known ancient settlement of the Valley, the village of Askra, home of the poet Hesiod.

At the conclusion of our several seasons in the Valley we succeeded in identifying a minimum of 53 archaeological sites of all periods (Figure 2: sites in the south-west survey area marked «VM» and «Neo»). We would certainly now suspect that this figure deserves multiplying up, to represent the likely original number of sites. For the dominant majority of sites, occupied in Greco-Roman and Medieval times, at least multiplication by a factor of two seems appropriate, whilst on theoretical considerations the small figure for prehistoric sites deserves multiplication by a considerably larger factor to encompass the probable original complement of prehistoric settlements (Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1985).

These daims require explanation. The representativity of those ancient and medieval sites found by the original field survey has been clarified by our habit of regular revisiting of locations in later years. This has shown — as in Italian field survey experience — that surface sites appear and disappear with the various stages of the annual cultivation cycle, and on a longer-term and more discontinuously with the effects of deep-ploughing and other forms of more drastic disturbance of the subsoil. Our suggestion that there probably once existed twice as many ancient and medieval sites as recorded, is a working model that at least sets into scale the known distribution and its density. As for the prehistoric sites, our thoughts on the «taphonomic» problems of prehistoric surface sites in Greece echo those voiced some years ago by Jerry Rutter (Rutter, 1983) and for Italian survey by Stoddart and Di Gennaro (Di Gennaro and Stoddart, 1982). The generally low level of technical skill exhibited by typical Boeotian prehistoric ceramics, the high proportion of coarse wares, and above all, the progressive destruction by mechanical and Chemical processes of surface potsherds in a semi-arid environment (Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1988c) calibrated against time, have led us to the inevitable conclusion of gross underrepresentation of the characteristic small prehistoric rural sites in the Greek landscape even within intensive surveys. This hypothesis can we believe be verified in the following fashion: a typical small Classical farmstead with a scatter of say 30m diameter may yield several hundred to several thousand surface potsherds and tiles; the equivalent farm for one or two families in the Bronze Age may yield some tens of sherds over a similar size of spread.

At the present time we are restudying all the ceramic data from the Valley of the Muses for computerisation, so as to produce a definitive map of known sites within a G.I.S. (Geographical Information Systems) framework. That process will produce minor changes in the distribution of historic sites, and essentially such revisions affect small sites rather than the larger settlements where sampling problems are less likely to occur. If we decide, however, as is likely, that the presence of two or three prehistoric sherds together on a single location should represent a vestigial small rural site, then our previously-published distribution of prehistoric sites will be considerably increased. Moreover, since these tiny collections are usually a side-effect of intensive collection on historic sites, or casual finds in offsite fieldwalking, they may well represent the «tip of the iceberg» of surviving prehistoric activity foci in the Valley. A resurvey of the area concentrating entirely on prehistoric surface material would be advisable — far slower and more difficult than our completed survey — to investigate this «hidden» distribution. At the moment we can merely repeat our considered opinion, that even the updated prehistoric site distribution is a minimum one. This should come as no surprise, since the dense patterns of historic period maps presented by Greek field surveys usually represent periods of around 400 years; for Bronze Age and even more for Neolithic phases, a single map will represent from 600-2000 years or longer, with the expectation of far greater densities of sites if we make allowance for a series of relocation and abandonment phenomena coming into play.

On the other hand, as noted above, all these caveats are focussed on small sites, since the larger prehistoric sites have a far greater chance through numerical survival rates of catching the attention of surface survey. We would draw attention in the Valley to three sites in this substantial settlement group: the two tower sites (Pyrgaki and VM4) and their associated hillslopes, and the site of Askra — all are important Bronze Age foci. As our restudy of their surface finds continues, we may be able to comment on their possible role in the search for «Keressos», a secure refuge of the ancient Thespians with putative (earlier?) Bronze Age associations from its name. At present Askra appears to be a very extensive Early Bronze Age settlement and the Frankish tower/VM 4 site complementary with Middle to Late Bronze Age settlement; Pyrgaki hill has Mycenaean but probably also earlier Bronze Age material and perhaps Early Iron Age as well. At the outer exit from the Valley, we may also note that the Diaskepasi location of Palaeoneochori (site NEO 3), above the modem village of Neochori, is a rich site for most periods of the Bronze Age. Not surprisingly, the natural Siedlungskammer of the inner Valley itself seems always to have had at least one major community from earliest Bronze Age times to the 17th century AD, generally oscillating in location between the valley-floor Askra locality and the Frankish tower hill (VM4) above it.

As noted earlier, although we can only represent a very minimal map of small prehistoric rural sites, we can be much more confident that the larger, village-sized sites are all found. In the context of our wider survey of the Thespian chora we can suggest that the Askra/Frankish tower settlement complex forms one end of a chain of regularly, and closely-spaced, hamlets and villages of Bronze Age date spanning out from the Valley of the Muses towards Eutresis (cf. Figure 1), surrounded by a largely-hidden constellation of prehistoric farmsites. We may however need to exercise caution in estimating how large these Bronze Age villages were in population terms: Askra yielded Early Bronze Age material from many sectors of its 11ha maximal surface, yet it may be more appropriate to consider Kostas Kotsakis’s model (Andreou and Kotsakis, 1994) of sprawling, settlementdrift villages with houses separated by fields, than postulate a large, densely-built proto-urban community.

Evidence for post-Mycenaean activity in the Valley of the Muses, apart from intriguing recent finds on the lower, eastern slopes of Pyrgaki hill, is focussed unsurprisingly on the later historic village site of Askra, with limited finds of both Protogeometric and Geometric date. Once this location had been identified as the key ancient nucleated community in the Valley and therefore obviously Hesiod’s Askra (Snodgrass, 1985), we carried out a careful multi-level sampling exercise across the site to record the expansion and contraction of the occupied area over time (Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1988b). It was of course an important test of field survey sampling procedures that we recovered evidence appropriate to traditional chronology for Hesiod’s village, c.700 BC, and if we can go further and take the spread of finds as an indication of site size, then it must have been a very small community at the dawn of the Archaic age.

During Archaic times and certainly by high Classical times Askra can be seen to have expanded to its maximum size of 11ha (larger than a number of contemporary Boeotian small poleis), and we would suggest that a population of around 1300 people might be a reasonable figure (Bintliff, In prep.). My colleague Anthony Snodgrass has suggested that there may be traces of a stone defence wall of Archaic-Early Classical style, and if correct we might seek some correlation, either with the ancient tradition of conflict between Askra and its dominant neighbour Thespiae in Archaic times, or with threats to Thespiae and its satellites from Thebes. In any case, Hesiod’s account seems to indicate that already by the close of the Geometric era Askra was a dependent village of the polis of Thespiae with its corrupt nobles or basileis.

This maximal expansion at Askra, whether or not accompanied by resettlement by the Thespians after their semi-legendary expulsion of its original population, coincides not only with the much more extravagant expansion of Thespiae city itself to c.100 hectares (perhaps 13,000 people), but also with the infilling of the Thespian and Askraean countryside by small farmsteads and less frequently hamlets or large estate centres, accompanied occasionally by appropriately small (family?) cemeteries (Figure 3). The resultant picture obtainable throughout the Thespian and Haliartian chorai in high Classical times, and that now ciear from our work in recent years within the Hyettos chora far away in N.E.Boeotia, is a period of land use and population at a level never before and never again reached in Boeotia, with evidence of farms and land-use stretching well beyond recent cultivation limits. The habit of rural farm-dwelling, and the extraordinary density of manuring scatters also point to agricultural intensification, if not stress on resources, entirely predictable from independent estimates of 4th century BC Boeotian population at 150-200,000 people.

That general demographic and economic malaise that is seen in almost all regions of mainland Southern Greece during Late Hellenistic to Mid-Roman times (c.200 BC-400 AD) (cf. Alcock, 1993), finds its correspondence in the Valley of the Muses, at Askra and in the evidence from Thespiae city and its wider chora (Figure 4). Indeed it was here that the material to support Polybius’ gloomy comments was first presented in archaeological terms. It is worth offering, however, an interesting up-date on our previously-published discussion of rural and urban site abandonments and contractions for this period (Bintliff, 1991; Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1985). During the late 1980s and early 1990s the Cambridge team surveyed a district south of Thespiae city (not mapped in Figure 4), where it found much greater rural site continuity over this 600 year era, showing that although the town of Thespiae and the village of Askra shrank dramatically, accompanied by largescale loss of rural sites in the Thespiae chora as a whole, there were localised districts little affected by the general trend. This of course reminds us of the statement of Pausanias that Tanagra and Thespiae stood out as relatively prosperous in his time in comparison to the parlous state of the rest of Boeotia. It can now also be linked to Susan Alcock’s (Alcock, 1993) observation from other intensive surveys in Greece, that localised clusters of rural sites surviving into Roman times tend to be found immediately in the vicinity of urban foci.

In the subsequent Late Roman period (c.400-600 + AD), a general recovery of population and economy is found throughout Southern Greece, although locally there is much variability in its intensity. The Haliartos chora remains without an urban focus and correspondingly its rural recovery is subdued. In contrast the territory of Thespiae revives in both town and country (Figure 5). It is noticeable and indeed intriguing that whilst Askra recovers its full Classical extent of occupation and the associated Valley of the Muses rural network is extremely dense, Thespiae town registers only minor re-expansion on its confined Early Roman size and never begins to approach its Classical maximum, whilst its rural landscape has a less dense pattern of farm sites compared to that around Askra.

The average size of the Late Roman rural site is several times that of a typical Classical farm and merits the term «villa», whilst a number of these sites are large enough to be either substantial estate centres or small villages (eg VM 21 immediately west of modem Panayia village). Although therefore rural populations could well have exceeded Classical figures, if we bear in mind the likelihood that only 20-30 % of Classical Boeotian polis population resided outside of the city proper and the larger villages or komopoleis such as Askra (Bintliff, In prep.), then the failure of most Late Roman urban sites to revive to their earlier proportions forces us to acknowledge much lower overall population densities for the Late Roman era, whilst drawing attention to an apparent shift of emphasis to the countryside.

Askra’s unusual flourishing, especially around the large, ruined Medieval church in its south-central locality called Episkopi, seems to indicate that it has grown in status vis-à-vis Thespiae. A striking ceramic product may have been manufactured here — «Askra Ware» — a very hard grey-black pot, characteristically in flat shallow plates and dishes with distinctive stamped designs including Christian crosses. On the other hand, beyond the arguably mid-Roman small enceinte of spolia at Thespiae, (about the total area of the contemporary Askra settlement), there is an extramural community of size and importance too, not just indicated by abundant surface ceramics but the upstanding stumps of several brick structures of large proportions (basilican churches?).

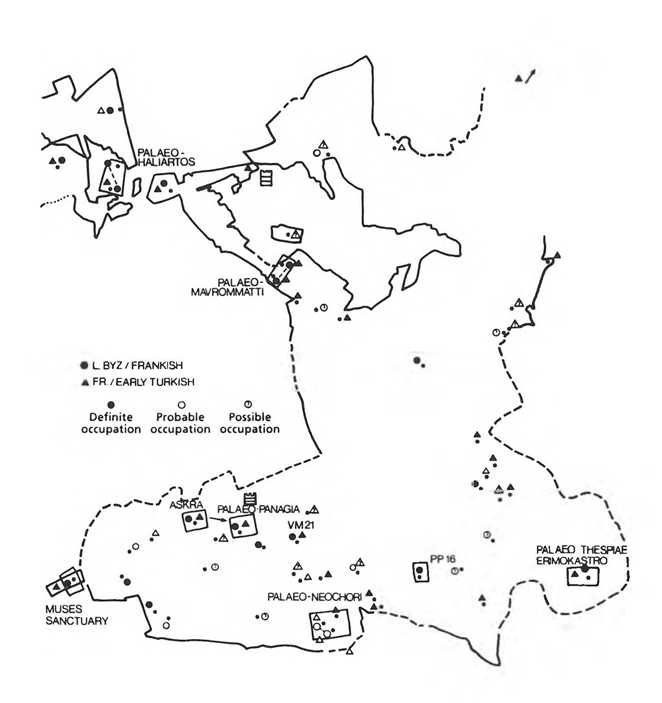

The Medieval periods from our survey data (Figures 6-7) are characterised by a pronounced emphasis on a small number of settlements that would seem to be of nucleated, hamlet-village nature, although genuine farmsites, if uncommon, seem to occur in most phases. This dominance of nucleated sites on the archaeological map already sets the Medieval settlement network apart from the ancient periods, and provides the model of recent traditional settlement in Boeotia with its almost exclusive emphasis on widely-spaced village settlement. On the other hand, as we have seen, Greco-Roman populations were mainly town-village based as well, so it is rather the fluctuations in a minority small rural site population component that we can highlight here.

We are currently conducting a major sub-project of the Boeotia Survey to establish a ceramic seriation for regional pottery from Late Roman to early 20th century, and this involves restudy of all our Medieval and Post-Medieval collections. Some provisional points can be made however as this work continues. We believe that in the immediate post-Roman period of the 7th-8th centuries AD (Early Byzantine), Boeotian populations survived in or beside ancient town and village sites, rather than fleeing to the mountains. Following the 6th century Black Death and politico-military breakdown in the provinces in the 7th century, local populations had already sunk to very low levels, allowing incoming Slav settlers to occupy abandoned land and in our view merge directly into local communities through intermarriage and eventual Hellenization. The latter hypothesis can be supported by the existence of a local «Archon of the Slavs» around 700 AD (pers.comm. from our Project Byzantinist, Archie Dunn), and by the Slav names of many «Greek» villages and of their occupants in 15th-16th century AD Ottoman tax records.

In the Thespiae chora, both the city site itself and Askra may well represent this pattern of survival as small villages throughout this troubled period, significantly providing surface ceramics of Medieval phases over those sectors particularly the focus of their Late Roman occupation. Thespiae is now essentially confined to the extramural village location east of the abandoned mid-Roman enceinte and hence understandably acquires the name Erimokastro; a Byzantine village appears in 13th century Frankish sources under that name when it is handed over as a fief to a Latin military order. In the late 17th century the English traveller Wheler (Wheler, 1682) records the population of Erimokastro as Greek and Albanian (with a few Turks), which in the context of the European travellers’ accounts is unusual amongst the predominantly Albanian villages elsewhere in lowland Boeotia. There are indeed reasons, which will be explained below, for viewing this ethnic mixture as a product of Wheler’s mode of description, in which a Greek Thespiae community derived from the ancient population (perhaps with Slav incomers) is treated together with a younger, close neighbouring village of pure Albanian origin (Leondari, formerly Kaskaveli/Zogra Kobili).

Askra seems to lose its ancient name and our Project Frankish specialist Peter Lock (pers.comm.) has suggested that it appears as the seat of a suffragan bishop of Thebes in Middle Byzantine and Frankish sources under the name Zaratoba/Zaratoriensis. By the 17th century the name Panayia is in use for this community and as this seems also to be the dedication of the large ruined medieval church in the heart of medieval Askra (Lolling, 1989)(1876)1, we might tentatively indicate a renaming under Slav influence by Middle Byzantine times (Zaratoba), then a second name change focussing on the village’s religious identification with the Virgin (Panayia). If Lock’s case is correct then Askra may have been a focus of Slav settlement amidst surviving Greek population. The reasons for the second change of name can be sought in the known later fate of this community in Frankish times, as we shall see below.

Aside from the two postulated, continuously-occupied nucleated sites of Thespiae and Askra, there are other early medieval sites in their district with less extensive occupational traces. Palaeoneochori — the predecessor of modem Neochori village — lying between those two ancient foci and at the outer entry to the Valley of the Muses, is not an important ancient site and seems to develop as a separate village from later Middle Byzantine times, perhaps a symptom of growing population and the recovery of imperial Byzantine control over the Central Greek countryside. There are indeed other small rural sites that appear to evidence growth and resettlement in the 11th-12th centuries AD (eg PP16 between Thespiae and Neochori, and an unexpected discovery — a small hamlet on the edge of the ancient Sanctuary of the Muses). All this is consonant with the signs of prosperity and security that allowed the construction at rural lowland Skripou (Orchomenos) across Lake Copais of its famous 9th century AD church, and later, just out of ancient Boeotian territory, the double churches of Osios Loukas in the 10th-11th centuries AD.

But there may also be signs of continuity from antiquity at smaller rural sites outside of the two urban Late Roman foci: a hamlet south of Thespiae (Thespiae South 14, south of the mapped survey area in our figures) has an unusual ceramic collection that could include Early Byzantine material alongside Late Roman and Middle Byzantine.

Despite the signs of growth and economic prosperity in S.W. Boeotia in the final Middle Byzantine centuries, a rising regime of great landowners and the decline of a free peasantry, such as has been documented throughout the Byzantine empire, seems to be locally evidenced through sources such as the 11th century AD Cadaster of Thebes (Harvey, 1983; Svoronos, 1959). The transition to an undeniably feudal regime in the early 13th century with the Frankish conquest may have made little obvious difference to Boeotian villages as they passed from a Byzantine secular/clerical landlord to some Latin equivalent.

One change of archaeological significance with the Frankish occupation was an apparent dispersai of landowners into the villages from which they drew their income. Peter Lock (Lock, 1986) has argued that the Duchy of Athens and Thebes had a different structure from the Principality of Achaea in the Peloponnese in lacking middle-status fiefholders. Below the ducal families resident in palaces on the Athens Acropolis and the Thebes Cadmeia there is rarely mention of named noble families, and this suits the archaeological picture with a notable gap between these urban castles and the isolated and usually smallscale feudal towers which arguably formerly coated the Boeotian and Attic countryside. There may have been some alteration in this pattern with the aggressive arrivai of the Catalans in the 14th century, when Livadhia castle become a significant new focus and we have a named lord in Chaeronea «castle» (Koder and Hild, 1976), but the general model of Latin minor knights or even lowlier, armed estate-managers occupying tower-residences for every one or two Greek villages seems to remain valid.

In the Thespiae chora the Erimokastro village is granted to the military religious order of the Premonstratians, perhaps to be connected to a substantial medieval church in the medieval sectors of the ancient city. Frankish ceramics are more plentiful than Middle Byzantine from our urban survey and seem to indicate continued growth in the settlement.

At Askra a complex situation is suggested from purely archaeological considerations, but this suits rather well the historic source material that has been attached to the site. As noted earlier, one of the five new suffragan bishops of Thebes which are created in later Middle Byzantine times as a clear sign of regional growth, is called the Bishop of Zaratoba. He is also cited as «of Zaratoba or Thespiae» and is certainly based near Thebes. Since Thespiae itself is known as Erimokastro and the core of medieval Askra has a toponym «Episkopi» it is reasonable to suggest that ancient Askra was the seat of this bishopric, and a connection to the very large medieval church whose ruins dominate the Episkopi locality can be sought. This being accepted at least provisionally, we can now introduce the important medieval village site which lies a mere half a kilometre above ancient Askra, our site VM4, on a sloping rocky hillslope dominated by the well-known Frankish tower. Our survey here shows a very consistent surface collection pointing to a 13th century foundation and 17th century abandonment.

Now «as it happens» there is a fascinating correspondence concerning the Latin bishop of Zaratoba (Lock, pers.comm.). Firstly he is very poor and needs bailing out by higher authorities; secondly he complains to the bishop of Thebes about the outrageous behaviour of a local «miles» or low-status military figure, who has been beating him up and burning his crops. With the knowledge that Byzantine Askra continues in use from its surface pottery through the Frankish era, parallel to the newly-founded and much more extensive village at VM4, we could suggest the following scenario: the village of ancient Askra (now called Zaratoba from Slav incomers to its community), is given as a fief to a non-noble Latin soldier of fortune, who erects a tower residence on a very defensible rock and resettles his new serfs closer to his keep. Meanwhile the Orthodox bishop has been replaced by a Latin bishop, who resides at Askra with a diminshed body of dependents; he will indeed have been hard put to extract much income from the Valley of the Muses with almost all its population and land in the power of a secular landlord uncomfortably close at hand. Not content, the VM4 «miles» finds sport in robbing the bishop of what he has left, then calmly going to Thebes itself to take mass.

Elsewhere we have evidence of continued hamlet life at Palaeoneochori (whose actual name at this time stili eludes us) and at even smaller farm and hamlet sites such as PP16, and the Sanctuary of the Muses. Although our continuing reassessment of deserted village ceramics may correct current impressions, there seems to be during early Frankish times (essentially the 13th century), in those areas we have intensively surveyed, a further expansion of population and settlement numbers over the Byzantine picture. Looking at Boeotia as a whole, and even allowing for the great likelihood that many if not most of the contemporary tower-residences have disappeared from our records, a map of those stili standing or recorded by 19th century topographers (Figure 8) bears a close resemblance to the very wide and even scatter of Classical poleis and komai across the Boeotian countryside (Figure 9). On the model we have favoured, of generalized continuity of Byzantine occupation focussed in nucleated village-hamlets on or near these ancient sites, which in turn determines the location of their controlling Frankish feudal residences, such a conclusion is not surprising. Apart from this suggestive physical contiguity of medieval and ancient monuments, we can point to the solid historic evidence (derived from Ottoman village censusses, see below), that at least from the 15th century AD onwards those Byzantine-early Frankish era villages that remain occupied at this time are usually Greek-speaking.

Despite this remarkable feature of continuity across the Dark Age divide into mature Frankish times, the same Ottoman archival sources which provide 15th century village ethnicity attributions bring to our attention a dramatic and permanent dislocation of traditional population, which we can reasonably date to the immediately preceding, later Frankish, period of the 14th and early 15th centuries AD. At the end of this postulated phase of terrible disruption, the new lords of Greece — the Ottoman sultans, in their generational village tax censusses or Defters, offer a first view, beginning in 1466, of a quite different ethnic landscape2.

The 1466 and 1506 Ottoman census maps (Figures 10-11), following my latest localisations of their named villages, reveal that Greek-speaking villages have disappeared entirely from Eastern Boeotia and are clustered in and around Mount Helicon; the two chief urban foci of Boeotia — Thebes and Livadhia — are also essentially Greek. Most rural Greeks are in unusually large villages, such as Ayios Dimitrios, Vrastamites, and Panayia. Eastern Boeotia has been completely recolonised by a new ethnic population, which has also settled widely in between Greek villages in West Boeotia: these people are ethnie Albanian immigrants or Arvanites. The earliest Ottoman censusses make it clear that almost every one of these new villages is both small and recently founded, and indeed a continuing process of settlement is observable over the first century of Ottoman rule, with both further, new foundations and primary Albanian hamlets splitting to form daughter foundations.

The Frankish historic sources inform us that the main Albanian settlement occurred during the final phase of Frankish rule (Jochalas, 1971), as a deliberate policy by the Catalan, Florentine and Venetian authorities to stimulate local manpower and crop production; Ottoman policy was to continue this practice. The reasons for an apparent volte-face after early 14th century references to military intervention to keep the Albanians out of Frankish Greece are not far to seek: massive depopulation from the mid-14th century Black Death, and escalating human and crop losses as a resuit of increasing warfare between the Franks, the Byzantines and Ottomans — especially noteworthy being Turkish pirate attacks. Significantly, not only are major ancient-Byzantine settlements resettled by Albanian immigrants (eg Akraiphnion and Orchomenos/Skripou), but we have growing archaeological evidence from our Project field investigations that villages whose only known history begins with Albanian settlement overlie abandoned Byzantine settlements (eg Archontiki, Yorgi Mavrommati, Rado Golemi).

What are the local effects of the «Late Frankish Shuffle» in the Valley of the Muses and at Thespiae? A microcosm of the wider trends seems indicated. The Frankish village at VM4, tucked away inside the Valley of the Muses, not only survives these traumas but seems to form a Greek refuge focus, expanding in Early Ottoman times from a large village of some 400 people in 1466 into a remarkably large village of some 1100 people by 1570. Its name, Panayia, should have been taken from the episcopal church of its ancestral community of Askra, probably at the time of its 13th century relocation. But at Erimokastro-Thespiae the village disappears from our sources after the Frankish period until later Ottoman times — reappearing, strikingly stili called Erimokastro in the 1642 census. In its immediate neighbourhood however, a new Albanian hamlet appears in 1466, that of Zogra Kobili (later called Kaskaveli and much more recently Leondari). Probably part of this story is the uneven occupation of the Palaeoneochori community between Thespiae and Askra: the Byzantine-Frankish village continues into Ottoman times and the late 16th century (as «Neochori») but then it disappears from village archives till early modera times, by which time it has moved several hundred metres downhill to its present location. Local oral tradition agrees with surface ceramics, with a story of abandonment during Turkish times and a recent refoundation. A reasonable hypothesis would be to suggest that Erimokastro-Thespiae was a victim of the troubled 14th-15th centuries, its Greek population abandoning the site for a «new village» in the safer location of Palaeoneochori hidden away in the hills (where they would have merged with the pre-existing Byzantine occupants of the site), and probably also helping to swell the population of Panayia. The ancient city locality was therefore, as elsewhere, deliberately pinpointed for Albanian resettlement by the late Frankish authorities. During the 17th century, a time of renewed disruption in the Greek countryside and widespread insecurity in lowland Boeotia in particular, the Neochori population moved back to Thespiae but preferred a defensible hill for the main seulement of Erimokastro, with a smaller cluster of houses on the plain below on the ancient city site. When Wheler visits «Erimokastro» in the late 17th century (Wheler, 1682) he writes of three clusters of houses, one being on the plain, and rather understandably merges into one village both upper and lower Erimokastro, which should be Greek, with the very close neighbour hill-village of Kobila (which remains unmentioned), which is entirely Albanian. Significantly, the Ottoman village tax records have Neochori making its final appearance in 1570 with c.300 people, and in the same year Kobila has c.200 people. In 1642 neither Neochori nor Kobila appear but Erimokastro reemerges with c.400 people (a reduction is normally observed throughout the region for 17th century village populations on 16th century numbers).

However, we must go back in time to the first 150 years or so of the Ottoman occupation to take note of the Golden Age that briefly enfolds Boeotia under the Pax Ottomanica. Freed from constant warfare and the ravages of disease, and brought into the tolerant sway of a low-tax, «hands-off» regime that allows local villages considerable autonomy, Boeotia, as the rest of the contemporary Ottoman Empire, enjoys a period of fast growth in both population and economy. This can be closely followed from the tax returns. Machiel Kiel (Kiel, in prep.) has used the economic returns from the Ottoman defters to demonstrate significant changes in land use as Panayia village, in line with almost every other community in Central Greece, doubles then almost triples in population from the mid-15th to late 16th century (Figure 12).

Initially, whilst the tiny Albanian hamlets (almost all less than 150 people) are only occupied seasonally for an extensive cereal and herding economy, Panayia and the other large Greek refuge villages keep stock low and focus on wheat, barley, vines and cotton. Over the growth period, however, cotton and vine production is reduced in favour of a major shift into sheep at Panayia (in 1506 a mere 30 head of sheep swells to 3,800 by 1570). Another product of more extensive land use is honey — the 60 hives of Panayia of 1506 grow to 192 by 1570. At the same time, the well-known development of water power and water management of the Arab-Ottoman world manifests itself within Panayia’s territory in a progressive increase of taxed water mills, from 5 in 1466 to 10 in the late 16th century; extensive traces of overgrown canals can be seen at various places in the Valley of the Muses, together with the fine upstanding stone overshot-wheel in the central Valley of the Muses and a second example by the entry to Neochori village. A final illustration of economic growth is Panayia’s ability to found a small monastery by 1540 and a second by 1570.

Although there remain a minority of Boeotian villages listed in the Ottoman archives which we cannot yet locate, we can put a minimal figure on the population of Boeotia within its ancient borders during this age of prosperity culminating in the late 16th century: a figure of around 40,000 people, one which compares closely to that of 1879 for a comparable area. In both periods the chief towns, Thebes and Livadhia, only manage to reach 5000 people each (Sauerwein, 1991). By 1981 Boeotia, notably larger than its ancient borders, has some 126,000 inhabitants, but the combined population of Thebes and Livadia stili only reaches 18,000. Classical Boeotia and its several large towns stili demonstrate far larger regional total and urban concentrations; Thespiae, not the only second order town in Boeotia, for example, may have had 13,000 people, whilst total regional population should have been around 200,000 people (Bintliff and Snodgrass, 1985).

Nonetheless, the Valley of the Muses in 16th century Ottoman times was exceptionally prosperous, and probably comparable to its Classical level of population and land use: if we place Classical Askra at 1300 people or more, and allow for a small additional population on isolated farms, we may still not much exceed the 1570 population of Panayia with 1100 people, plus a representative proportion of Neochori on the edge of the Valley with 300 people.

This favourable picture does not survive into the 17th century (Figures 13-14), when the inexorable decline of the Ottoman Empire sets in. Piracy and insecurity once again sweep away large numbers of villagers in lowland Eastern Boeotia, and many prosperous free villages suffer dismemberment into serf-ciftlik estates. The former problems seem to explain the abandonment of Neochori and the synoecism of villages at Erimokastro. Panayia suffers the latter fate, being broken up into some dozen serf-estates; by 1642 two-thirds of its population has disappeared, with numbers down to c.335 people. In clear connection with this catastrophic disjunction, the village focus shifts location at this period from the VM4/Frankish tower site some half-a-kilometre further east to its present location.

We do not as yet have specific archaeological or historical information on the final Ottoman era of the 18th century, although further research on the Western Travellers should prove rewarding; it now represents the «final frontier» for Greek archaeology as preceding centuries seem to be emerging into reasonable clarity! Our ongoing ceramic seriation project is beginning to separate the distinctive pottery of this period, and this will enable us to see better the subsequent developments on the ground; the Ottoman tax records of this era merely offer regional totals, but do seem to suggest a degree of recovery over the worst effects of the 17th century crisis (Kiel, in prep.). A long-term programme of study in Boeotia focussing on traditional vernacular housing (Lock, unpubl. Project reports) does indicate that from as early perhaps as the 17th century most villages, both Albanian and Greek in origin, consisted of «monochoria» or «makrynaria» (cf. Dimitsandou-Kremezis, 1986), single-storey longhouses for family and stock, often orientated north-south to favour outdoor tasks and indoor cool.

The first half-century after the traumas of the Greek Independence War was a difficult time for Boeotian villagers (Slaughter and Kasimis, 1986), and as late as the 1870s and 1880s banditry was severe enough to cause a final burst of village abandonments and mergers. At some stage Neochori was refounded, though now as an Albanian-Greek community, and Panayia was sufficiently recovered to reach c.925 people in 1896. The cereal-fallow-sheep/goat regime of the late 16th century at Panayia, with smaller amounts of vines, olives, cotton and other intensive crops, is still dominant not only in the Valley of the Muses but in most of inhabited Boeotia in the late 19th century and early 20th century, creating that stark, bare landscape in contemporary photographs. This is a powerful reminder that recent olivevine and scrub-covered landscapes such as met us in the Valley of the Muses in the 1980s, may look like scenes on ancient Greek vases but are culturally — and historically-specific rather than «natural» to the Greek lowlands.

As this capacity to surprise extends to the most recent trend to convert favourable parts of the Valley into fields of irrigated cash crops, we can only reaffirm the view several times expressed in this paper, that the Askra/Panayia basin, though seeming to be tucked away from the mainstream of life, is a microcosm of long-term transformations in the wider world of the Southern Greek Mainland.

Bibliographie

Alcock, S.E., Graecia Capta. The Landscapes of Roman Greece, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Andreou, S., and Kotsakis, K., «Prehistoric rural communities in perspective: the Langadas survey project», in P. N. Doukellis, and L. G. Mendoni (Ed.), Structures Rurales et Sociétés Antiques (pp. 17-25), Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1994.

Bintliff, J.L., «The Roman countryside in Central Greece: observations and theories from the Boeotia Survey (1978-1987)», in G. Barker, and J. Lloyd (Ed.), Roman Landscapes. Archaeological Survey in the Mediterranean Region (pp. 122-132), London, British School at Rome, 1991.

Bintliff, J.L., «Further considerations on the population of ancient Boeotia», in J. L. Bintliff (Ed.), Recent Developments in the History and Archaeology of Central Greece, (Oxford, Tempus Reparatum, in prep.).

Bintliff, J.L., and Snodgrass, A.M., «The Boeotia survey, a preliminary report: The First four years», Journal of Field Archaeology, 1985, 12, 123-161.

Bintliff, J.L., and Snodgrass, A.M., «The end of the Roman countryside: A view from the East» in R.F.J. Jones, J.H.F. Bloemers, S.L. Dyson, and M. Biddle (Ed.), First Millennium Papers: Western Europe in the First Millennium AD (pp. 175-217), Oxford, British Archaeological Reports, 1988a.

Bintliff, J.L., and Snodgrass, A.M., «Mediterranean survey and the city», Antiquity, 1988b, 62, 57-71.

Bintliff, J.L., and Snodgrass, A.M., «Off-site pottery distributions: A regional and interregional perspective», Current Anthropology, 1988c, 29, 506-513.

Di Gennaro, F., and Stoddart, S., «A review of the evidence for prehistoric activity in part of South Etruria», Papers of the British School at Rome, 1982, 50, 1-21.

Dimitsandou-Kremezis, E., Attica. Greek Vernacular Architecture, Attens, Melissa Press, 1986.

Harvey, A., «Economic expansion in Central Greece in the eleventh century», Byzantine and Modem Greek Studies, 1983, 8, 21-28.

Jochalas, T., «Über die Einwanderung der Albaner in Griechenland», Beiträge zur Kenntnis Sudosteuropas und des nahen Orients, 1971, 13, 89-106.

Kiel, M., «The rise and decline of Turkish Boeotia, 15th-19th century», in J.L. Bintliff (Ed.), Recent Developments in the History and Archaeology of Central Greece, Oxford, Tempus Reparatum, in prep.

Koder, J., and Hild, F., Hellas und Thessalia, Wien, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1976.

Lock, P., «The Frankish towers of Central Greece», Annual of the British School at Athens, 1986, 81, 101-123.

Lolling, H.G., Reisenotizen aus Griechenland 1876 und 1877, Berlin, Reimer Verlag, 1989.

Rutter, J.B., «Some thoughts on the analysis of ceramic data generated by site surveys», in D.R. Kelier, and D.W. Rupp (Ed.), Archaeological Survey in the Mediterranean Area (pp. 137-142), Oxford, British Archaeological Reports, 1983.

Sauerwein, F., «Bevölkerungsveränderung und Wirtschaftsstruktur in Boötien in den letzten einhundert Jahren», in E. Olshausen, and H. Sonnabend (Ed.), Stuttgarter Kolloquium zur Historischen Geographie des Altertums 2-3 (pp. 259-298), Bonn, Rudolf Habelt, 1991.

Slaughter, C., and Kasimis, C., «Some social-anthropological aspects of Boeotian rural society: A field reporte, Byzantine and Modem Greek Studies, 1986, 10, 103-159.

Snodgrass, A., «The site of Askra», in G. Argoud, and P. Roesch (Ed.), La Béotie Antique (pp. 87-95), Paris, CNRS, 1985.

Svoronos, N., «Recherches sur le cadastre byzantine», Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, 1959, 83, 1-145.

Wheler, G., A Journey into Greece, London, 1682.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

____________

1 Amongst the photographs taken by the French School Thespiae/Sanctuary of the Muses Expedition of the 1880s-1890s and kept in the Photothèque of the French School in Athens, there is one view which appears to show excavations at the Askra medieval church, hitherto unrecorded. The excavators of this partly uncovered large monument have previously been a mystery.

2 The Ottoman sources have been sought out, transcribed, translated and tabulated by the Project Ottomanist Dr. Machiel Kiel. Localisation of the named villages and preparation of the accompanying maps have been carried out by myself with the assistance of Dr. F. Sauerwein.