John Chrysostomos and Methodios at Montserrat

Six years ago we presented in Helsinki a new literary text on a parchment from Montserrat, P. Monts. Roca inv. no. 9951. We were able to determine that the text on the parchment contained elements of the text of Johannes Chrysostomos’ treatise De Virginitate, Chapter 73, lines 5-8 and 19-72. While the question of the precise nature and purpose of the text is still unsolved, this parchment from Montserrat is of particular interest and importance, because :

a) in general, there are not many publications of papyri and parchments of Johannes Chrysostomos available to date (the Leuven Database of Ancient Books cites only a small number of texts as coming from Egypt)2 ;

b) among these few texts there is no publication of any fragment containing a part of De Virginitate.

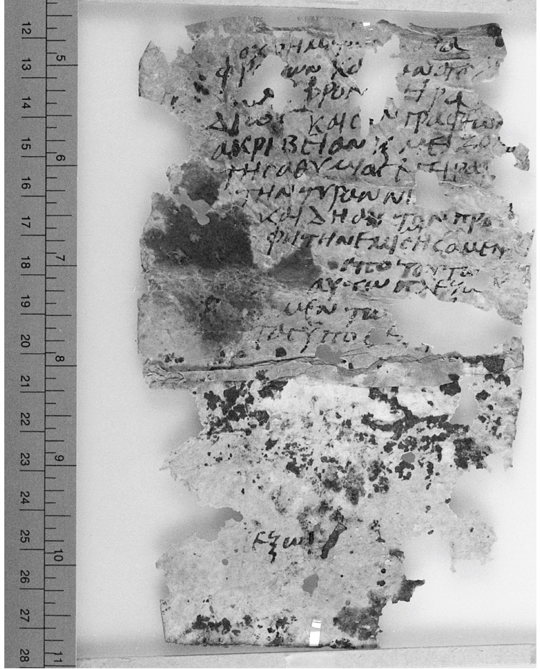

Now, six years later, we are ready to present a surprising new discovery among the parchment fragments kept in the same abbey that are probably related to the one mentioned above ; we will focus in particular on inv. no. 722. There is a certain physical similarity in that we are dealing again with a fragment of parchment, possibly cut – like the earlier one – from the edges of the skin used for producing parchment for codices3. The text is written rather carelessly, in a quick cursive, by a not really well-trained hand datable to the fifth/sixth century4. Regarding the text itself, we find again a text that comes close to Chrysostomos, while it is not exactly a copy of the standard text, but a condensed version ; and again, we are dealing with the treatise On Virginity, of which the previous fragment constituted the only papyrological evidence in 2004.

(I) P. Monts. Roca inv. no. 722 is a sheet of rather rough parchment made of two pieces joined by sewing with a piece of string. It features flesh and hair on both sides, since the two pieces were sewn together without making hair coincide with hair on the one side and vice versa.

Side 1

Hair 1 ὁ χρημάτων κατα - φρο̣ν̣ῶν κα[ὶ θ] ανάτου κ̣α̣τ̣α̣φρον[ήc]ειῥᾳ- δίωο καὶ cυ̣νγραφέων̣ 5 ἀκρίβειαν κ(αὶ) μείζον[̣ τῆc ἀθυμίαο ἐγεῖραι̣[ τὴν τυραννί[δα]. καὶ δὴ ἀν τὸν προ{ ̣ }- φητην ἐμιcήcαμεν· 10 ἀπὸ τούτω[ν] αὐτῷ πλέξω- μεν τῶ[…] τὰc ὑποθ̣έ̣c̣ε̣ε̣ι̣[c]. (stitches) | Joh. Chrysostomos, De Virginitate 81, 5 ὁ γὰρ χρημάτων καταφρονῶν ὁδῷ προβαίνων καὶ θανάτου καταφρονήcει ῥᾳδίωc |

Flesh

14 ἔξω

4 cυ̣γγραφέων 5 ἀκρίβειαν : - κ - ex corr. or smudged ? 9 μι ἐμιcηcαμεν parchment 13 ϋπο - parchment

He who despises material things, he shall also despise death easily (…) and the precision of (the) authors, and to awaken (?) the tyranny of despondency to a larger degree (?). And in fact we would have hated the prophet. On this basis, let us elaborate for him (…) the arguments. (…) To the outside.

9 The syllable -μι- of ἐμιcήcαμεν was added secondarily between the lines on top of the syllable -cή-, perhaps by a second hand.

12-13 If we reconstruct a genitive plural correctly, the position of the article τάc is not satisfactory. It should have been τὰc τῶ[ν …] ὑποθ̣έ̣c̣[ε]ι[̣c].

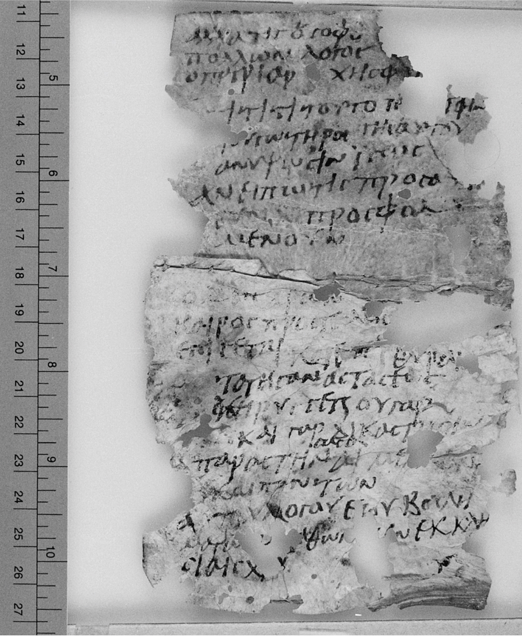

Side 2

| Hair | Joh. Chrys. De Virg. | |

1 ἀλλὰ τίc ὁ cοφὸ<c> [τῶν] πολλῶν λόγοο [ ] ὁ πατριάρ (hole) χηc φη̣[cίν] | (82, 1, 3) | ἀλλὰ τίο ὁ cοφὸc τῶν πολλῶν λόγοc ; ὁ πατριάρχηο φηcίν |

| – | ||

5 κ̣α̣ὶ τί {τί} τοῦτο π̣ρ̣[ὸc] τὴν̣ τ̣ο̣ῦ cωτῆροc {τ̣ῆc̣} αὐτοῦ ἀνύψωοιν ; ἴcωc ἂν εἴπω τιc προcα … | (73, 2) | καὶ τί τοῶτο πρὸc τὸν γάμον ; ἴcωc ἂν εἴποι τιc |

c̣ὺν δ̣ὲ πρὸ cφόδρ̣α̣̣ 10 μὲν οὖν(vacat) (stitches) | (73, 2-3) | καὶ cφόδρα μὲν οὖν πρὸο αὐτόν |

| Flesh | ||

11 ὁδὲ παρὼν καιρὸc πρὸc τέλοc ἐπίγεται καὶ ἐπί θύραι[c] τὰ τῆc ἀναcτάcεωc | (73, 5-6) | ὀ δὲ παρών καιρὸο πρὸ cτὸ τέλοc ἐπείγεται καί ἐπί θύραιc τά τῆc ἀναc τάc εωc |

|

15 κηρύccετ(αι).οὐ γὰρ | ἓcτηκεν | |

|

̣ καὶ γὰρ δικαcτηρίῳ παραοτῆναιcaca μέλλον- [τ]ε̣ο̣ καὶ πάντων (vacat)̣ m . 2 ? αὐτοῦ λόγου θ̣ε̣oῦ βουλη- 20 μάτων̣[ ] ̣θων̣ [ ̣] ἐ̣ν ἐκκλη- cίαιc Χρ(ιcτο)ῦ̣ (vacat) υ | (73, 41) | εἰ γάρ οἱ μέλλοντεc δικαοτηρίῳ παραοτή c ε c θαι, etc . |

1 ὁ parchment 5 τὴν : η corr. ex - ο - 7 ϊcωc parchment 8 1. εἴποι 13 1. ἐπείγεται 15 κηρυccετ() : κ ex corr. (-εc- ?) 19 λόγου : λ- ex ο corr.

5-10. We do not know why the author of our parchment made the jump backwards from De Virg. 82, 3 to 73, 2.

7. The noun ἀνύψωcιc « exaltation » occurs among fourth century Christian authors apparently only in Greg. Nyss. Contra Eunom. 3, 3, 43, 1, Athan. Synopsis Scripturae Sacrae (PG 28, p. 377, 39) and in Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum vol. 1, 1, 7 pg. 126, 19 (Council of Ephesus, AD 431).

11-14. Compared with De Virg. 73, 5-6, only the article τό before τέλοc is omitted.

19-21. The ink used by this second hand is different in color.

20. Alternately, read βούλημα τῶν, perhaps followed by ἀ̣[γ]α̣θῶν. We have speculated about reading αὐτοῦ λόγου θ̣ε̣οῦ βούλη|μα τῶν̣ ἀ̣[γ]α̣θῶν [τ]ὸ̣ ἐ̣ν ἐκκλη|cίαιc Χρ(ιcτο)ῦ, but we are very skeptical as regards the supposed omikron before ἐ̣ν, and we do not think that the resulting Greek text is coherent and produces good sense.

20-21. The word combination ἐκκληc ία Χριοτοῦ occurs before the sixth century only in Eus. Comm. in Ps. (PG 23, p. 813, 38), and in Procop. Comm. in Is. 1864, 31.

16. The edition of the text of chap. 73, 41-50 has :

(41) --------------------------------- εἰ γὰρ οἱ μέλλοντεc

(42) δικαοτηρίφ παραοτήcεcθαι τ/ῷ παρ’ ἡμῖν καὶ λόγον ὑφέξειν

(43) τῶν πεπλημμελημένων, τῆc κυρίαc γενομένηc ἐγγύc, οὐ

(44) γυναικὸc μόνον ἀλλὰ καὶ cίτων καί ποτῶν καί πάcηc ἐαυτοὺc

(45) ἀποcτήcαντεc φροντίδοc τῆc ἀπολογίαc γίνονται μόνηc –

(46) πολλῷ μᾶλλον ἡμᾶc τοὺc οὐκ ἐπιγείῳ τινὶ δικαcτηρίῳ ἀλλ’

(47) οὐρανίῳ βήματι παραοτήcεcθαι μέλλονταc καὶ ῥημάτων καὶ

(48) πραγμάτων καὶ ἐννοιῶν εὐθύναc ὑφέξειν, πάντων ἀφίcταcθαι

(49) χρὴ καὶ χαρᾶc καὶ λύπηc τῆc ἐπὶ τοῖc παροῦcι πράγμαcι καὶ

(50) τὴν φοβερὰν μόνον ἐκείνην ἡμέραν μεριμνᾶν.

Obviously, the scribe’s eye swerved from line 42 to the same wording in lines 46-47 and then copied words from 47 (μέλλοντ -, καί) and 48 (πάντων).

(II) P. Monts. Roca inv. no. 731, 20,1 [H.] x 4,3 [W.] cm, is a narrow strip of parchment, featuring irregular damage on the right hand edge of the hair side and at the bottom of the strip, possibly an edge of a skin, which contains a text written in a quick cursive hand on both sides5. The text on the recto turned out to be that of a Christian author, this time the church father Methodios, now attested for the first time in Egypt. Methodios died in 311 during the persecutions, so his life may be attributed to the period ca AD 250-311. He wrote a treatise titled Symposium sive Convivium decem virginum, a eulogy on the advantages and blessings of voluntary virginity, which does in fact match with the topic of the previously discussed two fragments of Johannes Chrysostomos6. It is remarkable that this is now the earliest extant fragment of the works of Methodios, the Patmiacus graecus 202 (an eleventh century codex commonly cited as ms. P) being thus far the earliest known source for his text7. The verso apparently presents a hitherto unidentified Greek literary prose text. As far as we have been able to establish, there is no clear connection between the texts on each side.

Recto : Hair

| Symposium | ||

|

1 εἴ τε οὖν γένεcιc ἔστ̣ι̣, οὐκ έχρῆ̣ν εἶναι νόμο̣[υc] | (8,16,72) | ἤτοι οὖν γένεcιc ἔcτι καί οὐκ ἐχρῆν εἶναι νόμουc |

|

5 ϊ[|ε|]ἡ ἀνάβα̣c̣ε̣ι̣[c] τοῦ Νείλου̣ ζω̣ή̣ ἐcτι κ̣[αὶ] χαρά ἑcτία[ιc.] |

||

τὰ λοιπὰ 10 ἐφεζῆε μνη- μονεύcαντεc ὡc ἔτι ἔναυλ[ον] τὴν ἀκρόα̣[cιν] ἔχειν μοι δ̣[οκῶ,] 15 πρὶν ἀπο- π̣τῆναι κ(αὶ) δ̣ι̣[α-] φυγεῖν ε̣ὐε- ξάλει̣[πτ]ο̣[ι γ]ὰ̣ρ̣ νέων ἀκου[c-] 20 μάτων [ μν̣ῆμα[ι] γερ̣[όντων] |

(3, 14, 35) | καὶ τὰ λοιπὰ ἐφεζῆc μνη- μονεύεαντεc ὧν ἔτι ἔναυλον τὴν ἀκρόαcιν ἔχειν μοι δοκῶ πρὶν ἀπο- πτῆναι καὶ δια- φυγεῖν εὐε- νέων ἀκου c- μάτων μνῆμαι γερ̣ [όντων] |

εἰc μέγ̣ [εθοε καὶ] κάλ<λ>οc [ἀρε-] |

(3, 8, 60) | εἰε μέγεθοε καὶ κάλλο cἀρετῆc |

|

25 τῆc, ὁ κα- τ’ {ατ}ἀζία̣ν̣ [τε καὶ] μέγεθοc̣ εἰπεῖν ἀδυ- ν̣c̣ τῶ · ο̣[ 30 [ὅ] μωο δ̣ [ (traces) …… | (3,9, 18) | κατ’ ἀζίαν τε καὶ μέγεθοc εἰπεῖν ἀδυ- νατῶ. ὅ μωο δ’οὐν |

Between 4 and 5 the parchment features a paragraphos 5 read εἰ, ἀνάβαcιc

Verso : Flesh

1 πολλοὶ μὲν γὰρ̣

[π]ολλάκιc ποι-

[ητ]α̣ὶ τυγχάνου-

[cι] τῶν ποιη-

5 μ̣άτων· οὔκ εἰcι

δ̣ὲ̣ δεcπόται.

[τ]ὸ̣ μὲν γὰρ

[τ]ῆ̣c τέχ̣ν̣ηc

[ἐρ]γάζον̣τ̣[α]ι̣, τὸ

10 [δ]ὲ̣ τῆc δεc-

ποτίac ἄλλοιc

παραχωροῶc[ι.]

π̣ολλοὺc λαν-

[θ]ά̣νει τῶν νό-

15 [μ]ω̣ν ἡ ἰcχὺc

π̣ροχείρωc

[κα]τά των έλευ-

[θ]έ̣ρων τολ-

μᾶν ἰωθό[ω]τωc

20 [… νο]μ̣ίζον-

τεc ἀ̣νδ̣ρ̣ί̣[α]ν̣

ε̣ἶ̣ναι τὴν ἀλό[γ-]

[ιcτο]ν̣ τόλμαν·

[…]ε̣ρ οὐδε̣ν

25 [……]ρ̣ε̣c̣

[……]δ̣ορη το

[… φ]ρ̣ονίμη

[οὐ δ]ίκαιον ὑ-

[π]ὸ ἀδίκου

30 [τ]υ̣πτηθῆ-

[ναι].

[…]δικην.

[… γ]ά̣ρ ὑβ̣[ρ

[…. ἀ]νθρω̣[π

35 [……].cυ[

……

10-11 δεcποτείαc 15 ϊcχυc parchment 19 εἰωθότωc (ϊωθο[ω]τωc parchment) 21 ἀνδρείαν 24 perhaps ουδα̣ν ? 25 ].ρ̣ε̣c̣ : the last two letters may belong to ink coming through from the other side 27 φ]ρονϊμη parchment 28 ϋ- parchment 33 ϋβ[ρ- parchment

Recto

1 εἴ τε . This is a iotacistic spelling or a variant of ἤτοι in the standard text. The resulting different syntax facilitates the omission (three words later in this phrase) of the standard text’s καί . It remains unclear why the author of our parchment jumps from one oration (8) to another (3) and even within the same oration (3, 14 > 3, 8 > 3,9) ; why he omitted between lines 11-12 the words μιμητικώτατα διέλθωμεν ; and why he wrote in line 12 ὡ c rather than ὧν (this occurs also in the eleventh century ms. P, on which see Debidour/Musurillo [1963] 33). The single ὃ (25) may be taken as a relative pronoun that connects the preceding passage with the following. It is not clear either what is the cause of the apparently divergent text at the end of 29 (it adds the beginning of an unexpected word in ο - right before ὃμω c) ; maybe only a dittography of ὃμω c ?

5-8. Remarkably enough, the text ϊ [ε]ἡ ἀνάßα̣c̣ε̣ι̣[c] (l. ἀνάβαcιc) | τοῦ Νείλου̣ | ζω̣ὴ̣ ἐcτι κ̣[αὶ] | χαρὰ ἑστία[ιc] « The rise of the Nile is (= “ means ”) life and joy for the families », does not occur in Methodios . The combination of ζωή + [5 words later] χαρά is found in several other Christian authors, among whom Joh. Chrys. In Epist. ad Philipp. (PG 62, p. 295, 48) and De Paenitentia (PG 60, p. 703, 55).

Verso

Parts of the text on the verso suggest that here one is dealing with a product of « Gnomic » wisdom written by an ancient pedagogue. The opening lines may thus be compared with [Joh. Chrys.], Ecl. i– xlviii ex diversis homiliis (PG 63, p. 655, 36) : πολλοὶ μὲν γὰρ πολλάκιc ἀρρωοτοῦcιν. Furthermore, a search in the TLG produced for 17-18, [κα]τὰ τῶν ἐλευ|[θ]έ̣ρων, a precise parallel with Basil. Caes. Epist. 270, 1, 5, while for 20-23, νο]μ̣ίζον|τεc ἀ̣νδ̣ρ̣ί[α]ν̣ | ε̣ἶ̣ναι τὴν ἀλό[γ]| [ιοτο]ν̣ τόλμαν, one finds a matching text in Thuc. 3, 82, 4 : τόλμα μὲν γὰρ ἀλόγιcτοc ἀνδρεία φιλέταιροc ἐνομίοθη. See also D.H. De Thuc. id. 17, 14 ; Plut., Quomodo adulator ab amico internoscatur, 56c ; Ael. Arist. Ars Rhet., 1, 1, 3[1], 5 ; Hermog. Περὶ ἰδεῶν λόyoυ 1, 6, 172. Remarkably enough, for most parts of the verso there seems to be no parallel available in the texts stored to date in the TLG ; see the notes below.

1-6. πολλοὶ μὲν γὰρ πολλάκιc ποιηταὶ τυyχάvoυcι τῶν ποιημάτων οὔκ εἰcι δὲ δεοπόται may be translated as « For many times many people happen to be the makers of poems [or, in general : creations/creatures ?], but they are not the masters/owners ». Apparently this phrase does not occur in texts already stored in the TLG. In itself, the topos of πολλοί + [after 4 intervening words] πολλάκιc occurs frequently enough in Greek literature between the third and the sixth century AD (such a TLG search produces ca. 200 attestations, half of which in John Chrysostomos). In a couple of Christian authors (among whom, again, John Chrysostomos) one finds a combination of words in ποιητ-, ποιημ- and δεοποτ- occurring together relatively closely (within 1 line of each other), but in each case the context is far from identical. Likewise, the combination of ποιημ- and δεοποτ- is a phenomenon found only in Christian authors, but never in a context comparable to our text. For illustrating the « Gnomic color » of this text, we refer to the (only partial) parallel expression in Men. Sent. 628 : πολλοὶ μὲν εὐτυχοῦcιν, οὐ φρονοῦcιν δέ.

7-12 τὸ μὲν γὰρ τῆc τέχνηc ἐργάζovται, τὸ δὲ τῆc δεοποτείαc ἄλλοιc παραχωροῦcι. This may be translated as : « For they work on (ἐργάζovται) the “technical” aspect (τὸ… τῆc τέχνηc) but they leave (παραχωροῦcι) the aspect of mastership/ownership (τὸ… τῆc δεοποτείαc) to others (ἄλλοιc). » A TLG search for a combination of ἐργαζ-+ παραχωρ- or τέχνη + δεοποτεία was unproductive.

13-23 πολλοὺc λανθάνει τῶν νόμων ἡ ἰοχὺc προχείρωc κατὰ τῶν ἐλευθέρων τολμᾶν εἰωθότωc […] νομίζοντεc ἀνδρείαν εἶναι τὴν ἀλόyιcτov τόλμαν. This may be interpreted as : « The force of the laws (ἡ ἰcχὺc τῶν νόμων) escapes (λανθάνει) many (πολλούc) <so as> to commit acts of cruelty (τολμᾶν) readily (προχείρωc) against their wives (κατἀ τῶν ἐλευθέρων), feeling in their usual manner (εἰωθότωc νομίζοντεc) that irrational recklessness (τὴν ἀλόγιcτov τόλμαν) is tantamount to (εἶναι) manliness (ἀνδρείαν). » However, the interpretation given to λανθάνει + an abstract subject ἡ ἰcχύc τῶν νόμων and connected with the infinitive τολμᾶν seems rather forced. For a similar « Gnomic » feeling, we refer to Men. Sent. 226 : εὔτολμοc εἶναι κρῖνε, τολμηρὸc δὲ μή. It is probably no coincidence that this section starts with πολλούc, after the preceding section on poems, poets, and owners of poems (1-12) started with πολλοί.

20. It is hard to propose a convincing solution for restoring the three letters lost in the lacuna.

27. It is again hard to propose a convincing solution for restoring the two letters lost in the preceding lacuna. Even so, one may wonder whether one should not capitalize Φρονίμῃ (not known to date as a woman’s name). This notwithstanding, the passage could be translated as : « For a wise woman (φρονίμῃ) it is not right (οὐ δίκαιον) to be beaten (τυπτηθῆναι) by an unjust person (ὑπὸ ἀδίκου). » But this raises the question whether a reversal in the elements « wise » (> « stupid ») and/or « unjust » (> « righteous ») would change the outcome ; in other words : is it acceptable for any woman to be beaten by any person ?

After presenting the two Chrysostomos fragments, inv. 995 and inv. 722, and the new discovery, inv. 731, offering a text by Methodios (writing also about Virginity), together with a passage that recalls Chrysostomos, we may sum up as follows. Our presentation of Christian parchments from Montserrat demonstrates :

a) a remarkable increase in texts reflecting phrasings and thoughts stemming from John Chrysostomos ;

b) the first attestation of the Christian author Methodios in Egypt on a parchment that is about five centuries older than the earliest medieval manuscript known to date.

In general, we wish to note that, as regards the study of early Christian texts, the collection at Montserrat has been remarkably prolific, because it has yielded not only a handful of new Chrysostomos (or at least « Chrysostomic ») texts and the new Methodios parchment, but, moreover, also a papyrus of Saint Hippolytos (see above, n. 3). Thus far, Chrysostomos was not frequently represented among Christian authors from Egypt, while both Methodios and Hippolytos were simply « unknown » in the list of such authors. We feel that their sudden appearance in this world, within the framework of the private papyrus collection of Ramon Roca Puig, can be explained more or less convincingly, but that this occasion is not the place and time to elaborate on this topic.

Bibliography

Cavallo, G./Maehler, H. (1987), Greek Bookhands of the Byzantine Period (A.D. 300-800) (BICS Suppl. 47, London).

Hagedorn, D./Torallas Tovar, S./Worp, K.A. (2007), « P. Monts. Roca inv. 65 verso again », ZPE 160, 181-182.

Musurillo, H./Debidour, V.-H. (1963), Méthode d’Olympe. Le banquet (Sources chrétiennes 95, Paris).

Nikolopoulos, P. (1998), Ta nea heuremata tou Sina (Athens).

Noret, J. (1977), « Le palimpseste grec Bruxelles, Bibl. Roy. IV.459 », Analecta Bollandiana 95, 101-117.

Politis, L. (1980), « Nouveaux manuscrits grecs découverts au Mont Sinai. Rapport préliminaire », Scriptorium 34, 5-17.

Torallas Tovar, S./Worp, K.A. (2007), « New literary texts from Montserrat : (1) A Fragment of Johannes Chrysostomos’ De Virginitate, Ch. 73 and (2) A New Papyrus of the Comparatio Menandri & Philistionis », in Frösén, J./Purola, T./Salmenkivi, E. (ed.), Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Papyrology, Helsinki 2004 (Helsinki) II 1019-1031.

Treu, K. (1975), « Ein Berliner Chrysostomos-Papyrus (P. 6788 A) », Stud. Patristica 12 (= Texte und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der altchristlichen Literatur 115, Berlin) 71-75.

Van Esbroeck, M. (1978), « Deux feuillets du Sinaiticus 492 (VIIIe – IXe siècle) retrouvés à Léningrad », Analecta Bollandiana 96, 51-54.

____________

1 See Torallas Tovar/Worp (2007). Papyrological research at Montserrat is financed by project FFI2009-11288, Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

2 See LDAB 564 (P. Köln VII 297) ; LDAB 2566 (Van Haelst 632 ; Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum P. 6788a : Treu [1975]) ; LDAB 2567 (Van Haelst 635 ; MPER NS IV 54) ; LDAB 2568 (BKT IX 15) ; LDAB 10859 (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale IV. 459, olim Phillipps 22406 [fol. 3, 37, 38], Noret [1977]. See also, from the Sinai, LDAB 7327 (Monastery of St Catharina Sinaiticus MG 78 ; Nikolopoulos [1998] 153, no. 78 descr.) ; LDAB 7470 (Monastery of St Catharina, 491 ; Politis [1980]) ; LDAB 117923 (Monastery of St Catharina 492 + St Petersburg, Russian National Library Gr. 835 : Van Esbroeck [1978]). AU of these Chrysostomos fragments, except for LDAB 564, belong to the category of Homiletic texts.

3 For the peculiar format of the piece (a vertical strip of parchment apparently not belonging to a codex, rather probably an individual note of theological content written on a discarded support), see the recently published vertical strips of parchment P. Oxy. LXXV 5023 (a mid/late sixth century Chairetismos to the Virgin) and 5024 (a sixth/seventh century Prayer to the Lord through the intercession of Maria). One may compare also a similar strip of papyrus, P. Monts. Roca inv. no. 65, on which see in latest instance Hagedorn/Torallas Tovar/Worp (2007) (St. Hippolytos’ De Benedictionibus Isaaci et Iacobi). See also the parchment fragments published in P. Köln X 409 (a sixth century interpretation of the Trinity) and P. Köln VI 256 (a sixth century theological text). Especially the latter text features a remarkable paleographical similarity to the Montserrat parchments discussed in this paper.

4 Comparing Cavallo/Maehler (1987) pl. 19c (second half of V AD), we would date this hand to the late fifth (or perhaps to the early sixth ?) century AD.

5 Again we may compare this to Cavallo/Maehler (1987) pl. 19c (second half of V AD), we would date this hand to the late fifth (or perhaps to the early sixth ?) century AD.

6 This text was edited by Musurillo/Debidour (1963).

7 On the transmission of the text of Methodios, see Musurillo/Debidour (1963) 31-38. On the codex P, see 41. One may add that some of Methodios’ extracts were preserved in the Sacra Parallela, and that our text may belong to a tradition of his works different from the one represented in the medieval manuscripts.