P. Enteux. 27 and the Nile transport of grain under the Ptolemies

This contribution is concerned in detail with just one, well-known, text – P. Enteux. 27 (= W.Chr. 442 ; January 28th, 222 BC). The context in which I seek to set it is, however, a larger one and one with a dual focus. I am interested both in the geography of Egypt, with the constraints of its climate and the annual flood of the Nile, and in Nile shipping, especially the shipment of grain which provided the main source of wealth for the rulers as well as food for the people of Egypt. The interplay of text and context is important. Both need to be understood if either is to be fully appreciated.

P. Enteux. 27, from the reign of Ptolemy III, is a petition from among the papers of the strategos Diophanes. Though at times the Greek is colloquial, its meaning is reasonably clear :

To king Ptolemy, greetings from Libys, naukleros of the Nile transport of Archidamos and Metrophanes with a capacity of 10 000 (artabas)1. I had letters for the Thebaid, but near Aphroditopolis there was a storm and my boat suffered damage to its yard-arm, so I was unable to make the destination specified in my letters of instruction. Because the Arsinoite nome was close, we dragged the boat to the harbour of that nome, with great effort and difficulty since we could no longer use the sails. We did not want to just end up here. So since it is regular practice, when a disaster of this kind strikes one of the naukleroi, to inform the local strategoi of the situation to stop ships being ruined held up where they are and problems ensuing with the transport downriver of grain, but rather to make sure that the ships are loaded full in accordance with the letters provided from the capital, I beg you, sovereign, to order Diophanes, the strategos, to investigate and, if what I have written is the case, to instruct Euphranor, who is responsible for grain in the lower district, to load my ship full with grain from his area with all speed on the authority of the existing letters. For the ship is large and, with the water retreating, even empty it is in danger of not getting back to the capital. But with your help, sovereign, we may (…). Farewell.

I swear by king Ptolemy and queen Berenice, and by Sarapis and Isis (…) [that this is a true account].

The docket on the verso summarised the contents and provides a date (January 28th, 222 BC).

Nile shipping and the system of grain transport have been thoroughly studied and this petition shows how things worked in practice2. The actual shipowners were regularly Greeks. Some were members of the royal family, often queens, and others came from prominent Alexandrian families3. Archidamos and Metrophanes in P. Enteux. 27 are not otherwise known. The barges were hired out to contractors called naukleroi, who carried the risk of the voyage, the hazards of shoals, wind and storms (as here), of pirates and other marauders4. These too were often Greeks. Ship-captains in contrast were normally Egyptians, whose local knowledge of the river and its hazards would serve them well. The transport of tax-grain was centrally organised. Contractors, who might or might not sail with their ships, undertook to collect grain from a specified point. Provided with letters of authority from head office in Alexandria, they used these to collect their load from the granaries where they were sent (in this case the Thebaid). As we know from other texts, documents were exchanged at the port and, at least at a later date, a sealed sample might accompany the load downstream to act as a check on purity5. Armed guards would often accompany the cargoes of grain.

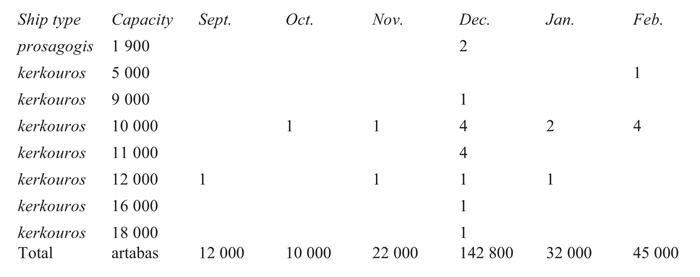

Nile barges used for grain were known as kerkouroi6 ; that with a capacity of 10 000 artabas (c. 252 metric tons) described by Libys as mega « large » was actually of moderate, even standard size, as can be seen from the following table which shows vessels leaving Ptolemais Hormou over the winter season of 172/171 BC, from the same port, that is, as Libys had ended up in some fifty years before.

Nile shipping out from Ptolemais Hormou : P. Tebt. III 856 (172/171 BC) :

Besides two smaller ships (prosagogides) with a capacity of nineteen hundred artabas, kerkouroi provided the main means of transport, ranging from one with a capacity of 5 000 artabas to one of 18 000 (carrying over 450 metric tones) ; there were twelve, like that of Libys, of 10 000 artabas7.

The pattern of traffic illustrated in this report is also of interest. September was the height of the flood and only one kerkouros left this month, when the water will have been dangerously high. The pace of departures and size of ships built up in the following months, with by far the heaviest traffic in December, when the flood was over but the Nile still flowed with a good stream, not yet starting to go down as it would in February or March8. In April, the new harvest would start, so as far as possible the granaries needed clearing in advance. The patterns of agriculture and shipping were closely intertwined, and that found here is supported also from the evidence of individual texts.

Sailing along the Nile was not only a risky but also quite a leisurely business. The prevailing wind and the current might cancel one another out to make travel upstream and downstream much the same in terms of time9. The river ran the length of the country, with 1 200 km (out of a total length of 6 825 km) within the borders of Egypt. Alexandria to Luxor (serving here for the Thebaid) is a distance of approximately 885 km10. Steve Vinson reckons 30 km a day as an average distance to sail. From Alexandria to the Thebaid would, therefore, be 33 days without a break, say a trip of one and a half months allowing for some rest en route. The 335 km to Aphroditopolis, however, where – we are told – a storm damaged Libys’ ship would be eleven days without a break. But the ease or difficulty of movement along the Nile depended also on the flow of the stream, and that of course depended on the time of year and the state of the flood.

The description of what happened next – unable to sail, they hauled their boat a further 40 km along to the harbour of the Arsinoite nome – implies a continuation of the Bahr Yusuf canal running along the north-eastern edge of the Fayum, as may be seen, for instance, on the detailed map provided by Tomasz Derda in his study of the Roman administration of this nome11. As they dragged their barge along from the bank, a further 2-3 days’ travel would be needed to reach Ptolemais Hormou where the letter was written. The earliest that Libys can have left Alexandria will have been some fifteen days before, sometime around the middle of January.

In all these calculations, we need to build in a margin of error since it is well known that the Nile has moved. We cannot be sure of either the geography or the climate of the area in the Ptolemaic period. Nevertheless, until the construction of the first Aswan dam in 1902 the pattern of the Nile flood was probably much the same. The river started to rise in July and reached the height of the flood in August-September when travel was dangerous on the river. In the three months from October to November the flood was receding. In December to January it went down a little further. In February it was still lower, but only became really low in March.

The effect of the flood is readily seen on the departures listed in the table above. So, in 171 BC three kerkouroi left in January, with five further departures in February made up of four barges the same size as that of Libys’ and one of half that size. Libys wrote at the end of January and early February was indeed a good time for a ship filled with grain to be sailing from the Fayum, but first it needed clearance for loading. And when Libys writes in late January of a decrease in flow of the Nile, he may be over-stating the case a little (in the hope, I assume, of getting grain for his hold)12 ; but at the same time he alludes to a well-known feature of relevance to Nile transport.

How then do these physical constraints affect our understanding of this text ? The Thebaid was the destination for which Libys had papers. Allowing time to fill his ship with grain once he arrived, Libys’ trip from Alexandria to the Thebaid and back would have needed something under three months13. Since Libys left Alexandria only in mid January, his return would be timed for mid April when the river was really low. There is something worrying about this timetable and it is worrying from the start. We should return to the text.

Near Aphroditopolis, Libys suffered a storm which damaged his rigging. Why, one wonders, did he not limp into that harbour to attempt a repair ? Instead he continued south in a ship which could not sail, dragging his boat some 35 km further along the inland canal to Ptolemais Hormou. Why did Libys do this ? The answer, I suggest, is clear. He was concerned to fill his ship and, of all regions in the Nile valley, the Arsinoite nome was without doubt the most productive. Ptolemais Hormou was the best centre to find a load of grain, with or without official papers to that end.

I am prepared to go even further. Despite its concluding oath, there is, I find, something suspicious about this whole story. Libys was sailing late in the season – almost too late – for a grain run to the south. That was his official destination, but maybe he already had other ideas from the start. I should like to voice the suspicion that he even planned a « disaster » from the outset, taking a gamble on getting official clearance for a load from closer to home rather than sailing south, where despite the best endeavours of central planning he might or might not have found the grain designated to fill his ship. And sailing from the south so late he would certainly have experienced problems from low water on the journey home.

It may be that I am over-suspicious but, taking account of all the factors involved and recognising the likely limitations to the efficiency of the system, the balance of the evidence is, I believe, against taking this petition at face-value. In my view, Libys, the naukleros, knew well what he did and what there was to be gained.

Bibliography

Casson, L. (1995), Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World (rev. reprint, Baltimore).

Derda, T. 2006, APCINOITHC NOMOC. Administration of the Fayum under Roman Rule (JJP Suppl. 7, Warsaw).

Hauben, H. (1997), « Liste des propriétaires de navires privés engagés dans le transport de blé d’Etat à l’époque ptolémaïque », APF 43, 31-68.

Meyer-Termeer, A. (1978), Die Haftung der Schiffer im griechischen und römischen Recht (Zutphen), with P. Köln X 416, introduction, for supplement.

Poll, I.J. (1996), « Ladefähigkeit und Grösse der Nilschiffe », APF 42, 127-138.

Thompson, D.J. (1983), « Nile Grain Transport under the Ptolemies », in Garnsey, P./Hopkins, K./Whittaker, C.R. (ed.), Trade in the Ancient Economy (London) 64-75 and 190-92.

Said, R. (1993), The River Nile : Geology, Hydrology and Utilization (Oxford).

Vélissaropoulos, J. (1980), Les nauclères grecs. Recherches sur les institutions en Grèce et dans l’Orient hellénisé (Paris).

Vinson, S. (1998), The Nile Boatman at Work (Münchner ägyptologische Studien 48, Mainz).

Willcocks, W. (1904), The Nile in 1904 (London).

____________

1 252 (metric) tons at 25.2 kg wheat to a Ptolemaic artaba ; see Vinson (1998) 175.

2 For earlier discussions, see Meyer-Termeer (1978) ; Vélissaropoulos (1980) ; Thompson (1983). The system found working in a second-century BC sitologos archive is studied by its editor P. A. Verdult, P. Erasm. II, p. 8-12 and 67-77, and in two first-century archives by P. Sarischouli, BGU XVIII.

3 Hauben (1997) remains basic, with his earlier studies on royal and female owners, on naukleroi and Nile skippers listed at p. 31, n. 1.

4 Bad weather : P. Hib. I 38, 4-15 (252/251 BC), ship capsizes ; P. Oxy. XLV 3250, 23-24 (AD 63) ; P. Oxy. Hels. 37, 6-8 (AD 176), also bad men. Pirates, etc. : P. Hib. II 198, 110-22 (243/242 BC) ; P. Lond. III 948, 8 (AD 236). Other hazards included annual changes to the bed of the Nile as a result of the flood and illegal levies added to regular tolls.

5 E.g. BGU XVIII 2755, 10-12, deigma (78/77 BC).

6 See Poll (1996).

7 Poll (1996) provides a record of the capacity of different ships.

8 On the period of low Nile (March-June, with May the lowest), see Willcocks (1904) 194 and 203.

9 See Vinson (1998) 56.

10 See Willcocks (1904) 123-24 ; Said (1993) 96-101.

11 See Derda (2006) 21.

12 In P. Enteux. 27, 15, anachorein is used in the sense of « retreat » or « retire ».

13 The lack of deep harbours in Upper Egypt regularly necessitated the use of lighters for shipment between the shore and the barge.