Bilingual graffiti from the Ptolemaic quarries at Akoris and Zawiyat Al-Sultan

Introduction

For almost thirty years now, excavations have been carried out by the Akoris Archaeological Project at Tenis/Akoris (modern Tihnha el-Gebel) in Middle Egypt2. This site is rich in archaeological and epigraphical evidence, which enables us to examine the changing conditions of a rural settlement situated between the major political centres of Upper and Lower Egypt from the fifth Dynasty (c. 2494 – 2345 BC) to around AD 700. For the Greco-Roman period, the social and economic background of the monumental votive inscription for Ptolemy V (OGIS 94 ; 199-194 BC), which had long been the sole physical evidence of Hellenistic occupation of this site, has been amply elucidated through our excavations in the northernmost area of the settlement between 1997 and 2001. The imported Rhodian and other Mediterranean amphora stamps from the deposit eloquently testify that the dressing and export of large limestone blocks from nearby quarries was an important industry in Hellenistic Akoris3. Since 2005, we have been conducting a survey of the open-air limestone quarries near Akoris and at Zawiyat al-Sultan about 12 km south of Akoris on the east bank of the Nile, where an impressive Ptolemaic quarry is located4. This survey has led to the discovery of a vast number of Greek and demotic, often bilingual, graffiti left on the walls and ceilings of the quarries as briefly announced at the last papyrological congress in Ann Arbor in 20075. On this occasion we would like to offer a more comprehensive discussion of the evidence based on the most recent results of the survey.

Examples of graffiti

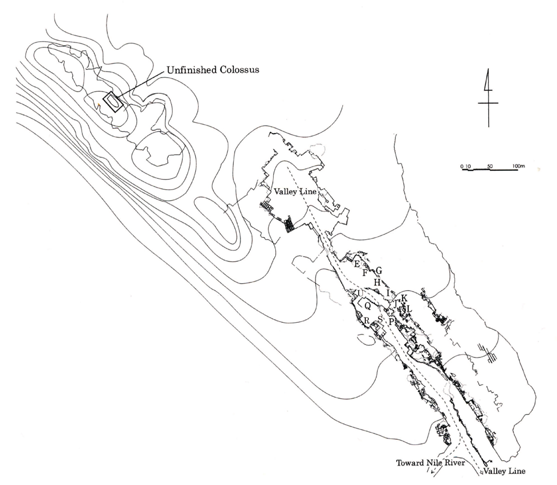

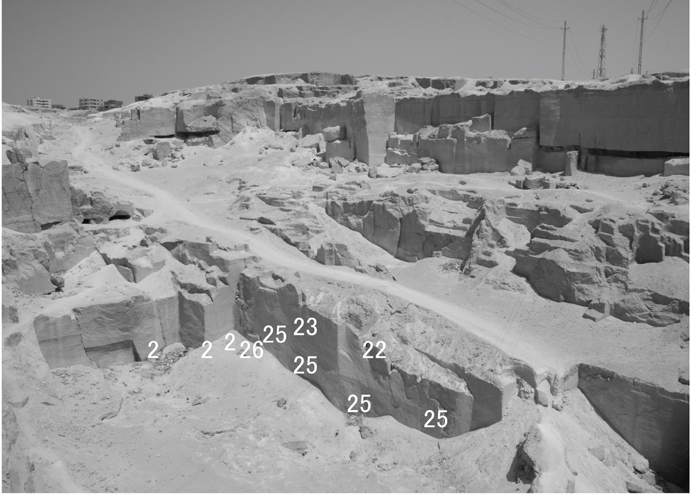

The ancient quarry at Zawiyat al-Sultan consists of a deep straight valley, the mouth of which opens toward the southeast (fig. 1 and 2). This conspicuous terrain, however, was formed not by natural processes but by the effects of quarrying. The graffiti of Ptolemaic date, which are written with red ink, are found unevenly throughout the valley, apart from areas disturbed in later periods. We have divided the valley into several sections, and have started to register graffiti at the sections named J, K, and L, where the densest concentration of graffiti can be found. These sections are on the east side of the upper part of the valley and were apparently used for procuring large flat blocks. We have registered more than one hundred graffiti here alone6. Three quarters of them are in demotic and the remaining quarter is in Greek.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

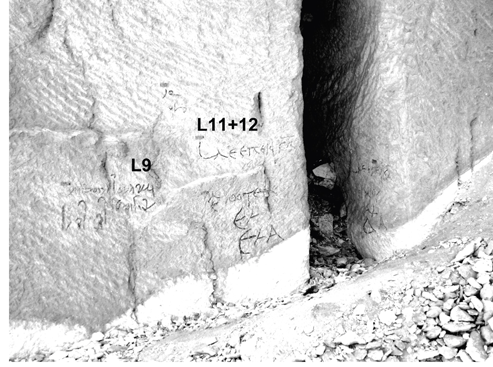

Below is a typical example of such a bilingual graffito preserved in good condition (L11 + 12 and L9 : fig. 3). Both the demotic and Greek versions provide three sets of information : 1) a date, 2) a personal name, and 3) tripartite numerals.

L11 + 12 : September 10th, 251 BC7

(ἔτουc) λε Ἐπεὶφ κα

ἐλ(ευθέρου ?) Θοτέωc

ε∠

ε∠ α

Year 35, Epeiph 21.

Of free quarryman (?) Thoteus.

5 ½ (by)

5 ½ (by) 1.

Fig. 3

2. λ is written above ε in superscript. Although not certain, ελ might be an abbreviation for ἐλεύθεροc or ἐλευθέρολατομοc ; a reference to the later appears in P. Petr. II 13, fr. 1, 1-2 (256 or 255 BC) in the genitive plural. We owe this remark to Prof. Willy Clarysse. The same abbreviation is also found in the Greek version of F36 cited below, and the demotic counterpart of F36 contains words rmṯ nmḥ, « a (male) free person ».

L9 ἰ bd 4 prt ἰ bd 1 šmw ibd 2 šmw Ḏḥwty- ἰ w 5 ½ r 5 ½ r 1 | The fourth month of « winter », the first month of « summer ». the of « summer ». Djehuty-iu. 5 1/2 by 5 1/2 by 1. |

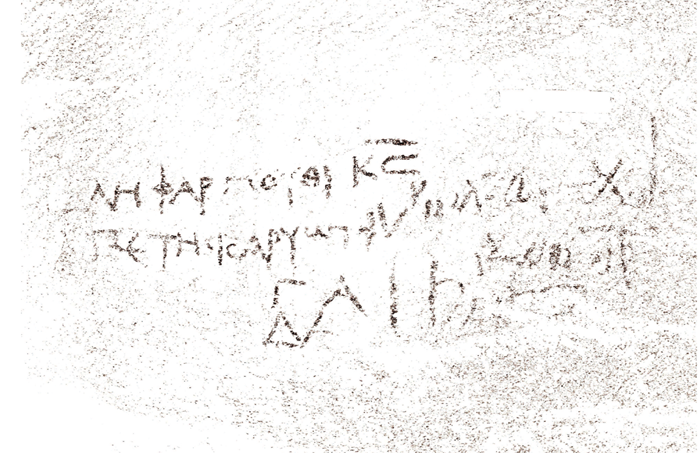

Despite the similar structure, however, the demotic graffiti in these sections are not always exactly identical to their Greek counterparts, as can be seen in the example given above, since they consistently lack a reference to the regnal year. But elsewhere there are demotic texts with regnal years and in such cases the equivalent regnal years are denoted by the Egyptian year, while the regnal year of Greek texts always uses the financial year. Below is such an example of typical bilingual graffiti (F36 : fig. 4).

F36 : June 16th, 248 BC Greek | |

(ἔτουc) λη Φαρμοῦθι κ ̅ ς ἐλ (εύθεροc ?) Πετῆcιc Ἁρυώτ (ου) γ α δ ∠ | Year 38, Pharmouthi 26.

Free quarryman (?), Petesis, son of Haryotes. 3 (by) 1 (by) 4 ½. |

Demotic ḥśbt 37 ιbd 4 prt św 26 rmt_ nmh_ P3-ti-3s.t 4 ½ r 3 (r) 1 |

Year 37, the fourth month of « winter », day 26. A free person, Padiaset.

4 ½ by 3 (by) 1. |

Fig. 4

It seems to have been customary in the upper part of the valley for the Greek texts to be accompanied by demotic counterparts, while a number of demotic texts especially on ceilings do not have equivalent texts in Greek. Undoubtedly the texts record an aspect of the quarrying process on site. The date usually indicates a certain day in the Greek version but a period in demotic, as the graffiti L9 and 11/12 show. But this is not always the rule ; as in F36, there are demotic texts indicating a specific day. The named person seems to be in charge of the quarrying ; the tripartite numerals most likely refer to the volume of stone extracted in three dimensions.

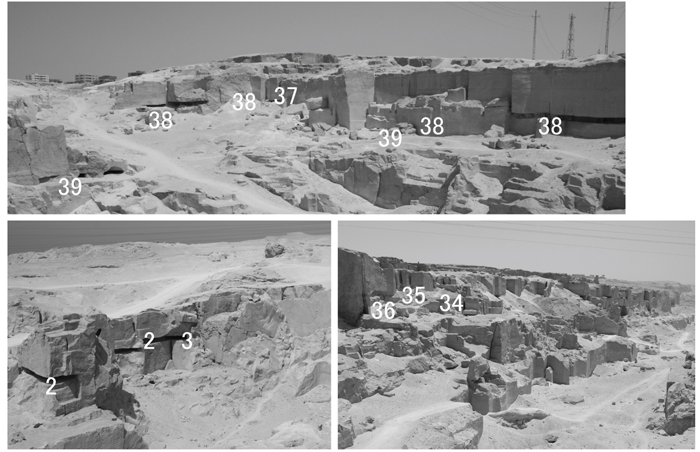

Graffiti in the 250s and 240s : the upper part of the valley

Among the nine Greek graffiti explicitly denoting years in Sections J and L, one case refers to financial year 34, seven to year 35, the remaining one to year 36. The evidence from the neighbouring sections in the upper part of the valley attests continuous years. As shown in fig. 5, the graffiti found on the walls of Sections E-I, which are on the north of Sections J-L, and on the ceilings of horizontal galleries on the west side (Sections R, S and U) provide years 37, 38, and 39, and years 2 and 3 respectively. These observations indicate that quarrying proceeded from the south to the north, namely from the mouth of the valley to the inner part. The sequence of the years also strongly suggests that these sections were quarried in the last years of Ptolemy II (reign : 285/284-246 BC), who died in his 39th regnal year, and the beginning of the reign of his successor Ptolemy III (reign : 246-222/221 BC). Thus quarrying of the upper part of the valley was in operation in the late 250s and 240s.

The quarrying activities seem to have peaked particularly in the 38th financial year of Ptolemy II. At Section E, all the legible Greek graffiti, twelve in number, refer to the months Mecheir, Pachon, or Pauni of year 38. Also at Section F, all sixteen legible Greek graffiti show that works were in progress here from Tybi of year 37 to Mesore of year 38. This means that activities at the northeastern corner of the upper part of the valley were quite intensive in early 248 BC. The graffiti on the ceiling of Section H, a horizontal gallery dug to the south of these sections, reveal that further exploitation was attempted in year 39. For some reason or other, however, the plan was quickly abandoned.

Fig.5

Graffiti in the 220s : the bottom of the valley

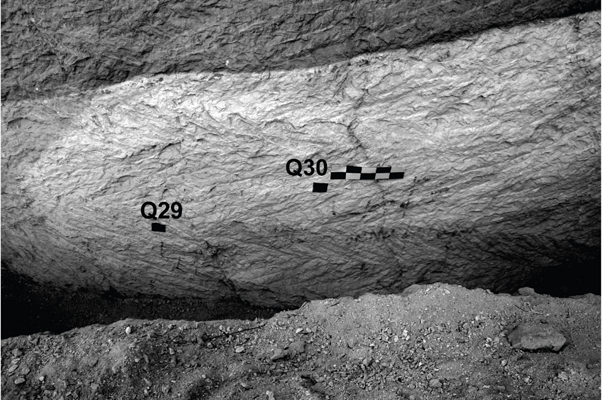

So far we have discussed the demotic and Greek graffiti from the upper part of the valley. Both sides of the bottom of the valley also provide a number of graffiti, but conspicuously they are written only in Greek. Here too the sequence of regnal years affords a valuable clue to their possible date. In Section Q, which is located on the innermost part of the bottom of the valley, there is a series of financial years from 22 to 26, and also reference to year 2 (fig. 6). It seems certain that quarrying activities progressed here in the last years of a certain king, whose reign terminated in his 26th year or soon after, and in the first years of the next one. These kings are most likely Ptolemy III, who died in the course of his 26th regnal year, 222/1 BC, and Ptolemy IV (reign : 222/221-204 BC).

Fig. 6

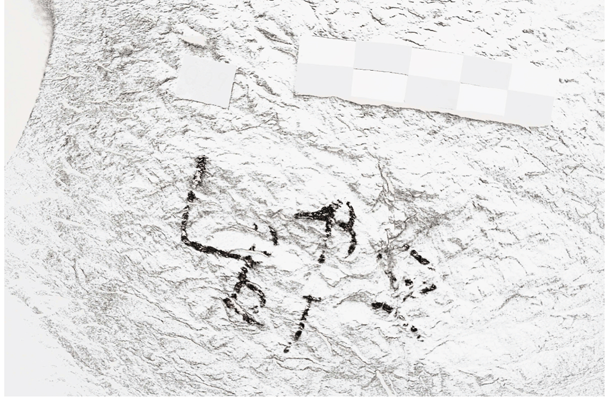

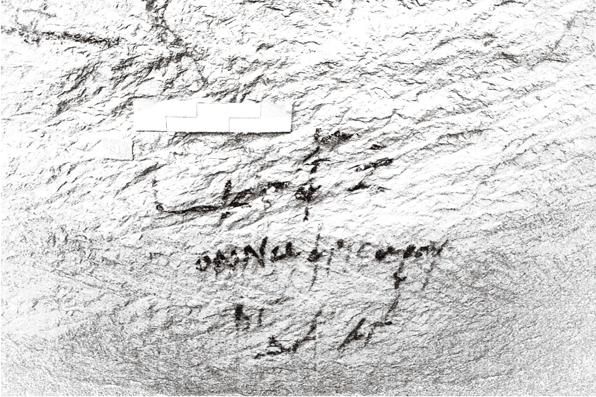

This view is supported by evidence from two adjoining graffiti, Q29 and Q30 (fig. 7-9). They are written in Greek and appear side by side on the vertical quarry face near the northeastern corner of Section Q. Both graffiti are written with a narrow brush in a cursory style and are accompanied by the names of months in abbreviation forms.

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

| Q29 : May 21st, 221 BC | |

| (ἔτουc) β Φ̣α̣ρ̣ (μοῦθι) ζ ̅ | Year 2, Pharmouthi 7. |

1. The reading of the month is not certain. But it is most probably Pharmouthi abbreviated to the first three letters. The loop of φ seems eroded. The α is superscript on the φ in the form of a « Haken-alpha », the horizontal line of which curves toward the bottom. The semi-circle of ρ is written on the upper right of the vertical stroke. On the combination of φ and ρ, see Pap. Lugd. Bat. XXI 573. A φ with a superscript α also appears in the text below Q30. Another close parallel in CPR XXVIII 13, 28.

Q30 : November 23 rd, 222 BC | |

(ἔτου c) κς Φαῶ (φι) ζ | Year 26, Phaophi 7. |

Ὀννῶφριc Ὥρου | Onnophris son of Horos. |

β γʹ | 2 ⅓ (by) |

δ ∠ ∠ γʹ | 4 ½ (by) ½ ⅓. |

1. Phaophi is written as an abbreviation of the first three letters. The α in « Haken-alpha » is written above φ. The ω is written above them.

While Q29 has no corresponding numerals and the reading of the abbreviation indicating the month is not certain, the reading of text Q30 is clear. It is located a little bit higher than Q29, but horizontally the two are only about 60 cm apart. The spatial proximity of these two graffiti strongly suggests that they were written within a limited period of time. Year 26 should be the last regnal year of one king and year 2 probably represents the second year of his successor. This observation strengthens our view that the activities at Section Q were dated to the last years of Ptolemy III and the early years of Ptolemy IV.

A changing epigraphic habit

These two sets of sequential regnal years mentioned above strongly suggest that the quarry at Zawiyat al-Sultan was in operation in the middle and the latter half of the third century BC. It is highly remarkable that the manner of writing graffiti shows a distinct change even during this short period of time. The once so ubiquitous demotic graffiti completely disappear and are replaced with Greek ones alone. By the 220s, demotic seems to have lost its importance in recording the quarrying process, and the written language of administration at the quarry changed from bilingual (demotic/Greek) to monolingual (Greek).

Akoris south quarry

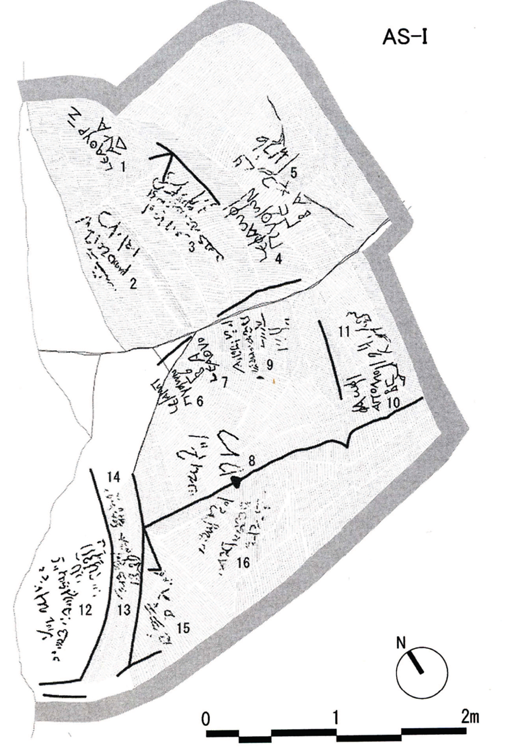

Recording the quarrying process in both demotic and Greek was practised not only at Zawiyat al-Sultan but also at the South Quarry of Akoris, located on the plateau just to the south of the site of Akoris. Although this quarry seems to have been exploited mainly in Roman times, a few remnants of Ptolemaic quarry faces have remained untouched until today. Three small horizontal galleries have been cut below the conspicuous projection in the middle of the quarry field9. Even though the outer face of the rock is heavily eroded and damaged by later activities, Greek and demotic graffiti on the ceilings are preserved in good condition. At least sixteen graffiti including five pairs of bilingual ones remain on the surface of one of the galleries, AS 1 (fig. 10, which was made by integrating drawings of the graffiti on a drawing of the ceiling). They are represented in exactly the same tripartite structure as the graffiti of Zawiyat al-Sultan. The regnal years explicitly show that these graffiti were recorded in the fourth and fifth year of a certain king. Although there is no sequential evidence, it is likely that they are contemporary with the standard bilingual graffiti at Zawiyat al-Sultan. This suggests that the king in question is Ptolemy III.

Fig. 10

Function of the graffiti

As has been noted above, a standard Greek graffito at this site is composed of three constituents : the date (year, month, and day), a personal name, and a set of three numbers. The last of the three numbers is usually one. According to Dr Takaharu Endo, our colleague in architectural history, these numbers represent the cubic volume of the removed rock, and the unit of length employed is about 54,0 cm, which is close to the royal cubit of dynastic times (52,5 cm). He further points that, where graffiti are written on vertical walls, the last of the three numbers corresponds to the width of narrow trenches made for quarrying stone blocks, which would have faced the walls with the graffiti, from the bedrock. Thus, the volume indicated by the three figures is probably that of a working trench rather than of a quarried stone block itself10. These graffiti, however, do not seem to be records of daily activities of workmen at the quarry. The references to the dates suggest that the graffiti were written for the purpose of official inspection sometime after trenches were quarried.

An observation of the graffiti on the ceiling of AS1 makes it possible to reconstruct the order of writing the graffiti. It would be a reasonable assumption that the graffiti on the ceiling close to the opening were written earlier than those of the interior of the gallery, but actually this is not always the case. At the gallery AS1 (fig. 10), the bilingual graffito AS1-1 (Greek) and AS1-2 (demotic), located near the opening, bear the date of 7 Hathyr of financial year 5 (December 28th, 243 BC), while another graffito on the inner ceiling AS1-4 (Greek) and AS1-5 (demotic) is dated to the previous month, Phaophi, of the same year. Moreover, two bilingual graffiti, AS1-7 (Greek) and AS1-8 (demotic), and AS1-6 (Greek) and AS1-16 (demotic), overlap diagonally on the same surface, but the former (December 243/January 242 BC) has a date of about half a year later than the latter (May/June 243 BC). Such an irregular manner of writing graffiti is also observed at some horizontal galleries at Zawiyat al-Sultan. Although there remain many aspects to be elucidated about the function of these graffiti, it seems certain that they recorded not the details of the daily operation but their inspection by official hands at irregular intervals.

Conclusions

We have discussed several aspects of the graffiti from the quarries at Zawiyat al-Sultan and Akoris : the graffiti bear dates from the middle and later third century BC ; the languages used for the graffiti changed from bilingual demotic and Greek to Greek monolingual ; the graffiti were written presumably not as records of daily work, but for official inspection. These graffiti surely contribute to our understanding of the history of Ptolemaic Egypt. The graffiti are a relatively neglected kind of written source for the study for Graeco-Roman Egypt and far less explored than papyri and ostraca. They shed fresh light on aspects of Ptolemaic administration about which papyri and ostraca reveal little. Unlike most papyri and ostraca, the graffiti retain their original physical contexts : the walls and ceilings of the quarry. So archaeological and architectural research may contribute to better understanding of the graffiti and vice versa.

In recent decades, scholars have explored the phenomenon of linguistic Hellenization in the administration of Egypt. Under the early Ptolemies, Egyptian scribes can be seen rapidly acquiring the ability to write Greek, as the result of the introduction of Greek as an administrative language promoted through Greek education, and the privilege it offered to Greek users11. If our interpretation in this paper is correct, it is tempting to connect the transition we have identified at the quarries at Akoris and Zawiyat al-Sultan from bilingual to monolingual Greek graffiti to the phenomenon of linguistic Hellenization more generally, suggesting that the phenomenon of linguistic Hellenization advanced rather rapidly in the mid-third century BC at this site in Middle Egypt. But further research is needed to confirm that the change indeed reflects a wider phenomenon, and not just the writing preferences of a handful of scribes. In any case, linguistic change is only one aspect of the phenomenon of Hellenization as a whole. The quarries also attest the continued existence of the traditional method of extracting stones and use of the royal cubit as the unit of measurement. As has been noted by Joe Manning in his recent monograph, we must appreciate how lengthy was the process of cultural contact between Greeks and Egyptians beginning with the Saite restoration12. While some aspects of life drastically changed in the early Ptolemaic period, other aspects remained unaffected or took a longer time to develop. The pace of cultural change at the local level was not so much constant as highly variable.

Bibliography

Endo, T. (2009), « Architectural Study on the Relationship between Red Lines and Graffiti found at the Underground Chambers of Unfinished Colossus », Cyber University Bulletin 1, 33-51 [in Japanese with English Summary].

Kawanishi, H. (1995), Akoris : Report of the Excavations at Akoris in Middle Egypt 1981-1992 (Kyoto).

Kawanishi, H./Suto, Y. (2005), Akoris I : Amphora Stamps 1997-2001 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (1998), Akoris : Preliminary Report 1997 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (1999), Akoris : Preliminary Report 1998 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2000), Akoris : Preliminary Report 1999 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2001), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2000 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2002), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2001 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2003), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2002 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2004), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2003 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2005), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2004 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2006), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2005 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2007), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2006 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2008), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2007 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S. (ed.) (2009), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2008 (Tsukuba).

Kawanishi, H./Tsujimura, S./Hanasaka, T. (ed.) (2010), Akoris : Preliminary Report 2009 (Tsukuba).

Klemm, R./Klemm, D. (1992), Steine und Steinbrüche im alten Ägypten (Berlin).

Manning, J. (2009), The Last Pharaohs : Egypt under the Ptolemies 305-30BC (Princeton).

Muhs, B. (2005), Tax Receipts, Taxpayers, and Taxes in Early Ptolemaic Thebes (Chicago).

Muhs, B. (2007), « Linguistic Hellenization in Early Ptolemaic Thebes », in Frösén, J./Purola, T./Salmenkivi, E. (ed.), Proceedings of 24th International Congress of Papyrology, Helsinki 2004 (Helsinki) 793-806.

Muhs, B. (2010), « Language Change and Personal Names in Early Ptolemaic Egypt », in Evans, T.V./Obbink, D.D. (ed.), The Language of the Papyri (Oxford) 187-197.

Shaw, I. (ed.) (2000), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford).

Suto, Y. (2003), « Texts and Local Politics in the chora of Ptolemaic Egypt : the Case of OGIS 94 », SITES : Journal of Studies for the Integrated Text Science 1-1, 1-12.

Suto, Y. (2006), « Text and Context of the Greek Graffiti at the Ptolemaic Quarry of Zawiet Sultan in Middle Egypt », SITES : Journal of Studies for the Integrated Text Science 4-1, 1-18.

Thompson, D.J. (1992a), « Literacy and the Administration in Early Ptolemaic Egypt », in Johnson, J.H. (ed.), Life in a Multi-Cultural Society : Egypt from Cambyses to Constantine and Beyond (Chicago) 323-326.

Thompson, D.J. (1992b), « Language and Literacy in Early Hellenistic Egypt », in Bilde, P. et al. (ed.), Ethnicity in Hellenistic Egypt (Aarhus) 39-52.

Thompson, D.J. (1994), « Language and Power in Ptolemaic Egypt », in Bowman, A.K./Woolf, G. (ed.), Literacy and Power in the Ancient World (Cambridge) 67-83.

____________

1 We thank Prof. Hiroyuki Kawanishi, director of the Akoris Archaeological Project, for facilitating our research, Prof. Sugihiko Uchida (Meirin College) for his reading of the demotic graffiti, Prof. Yoshiki Hori (Kyushu University) and Dr Takaharu Endo (Cyber University) for the architectural survey and measurement of the quarries, Prof. Shin-ichi Nishimoto (Cyber University) for drawing our attention to the quarry at Zawiyet al-Sultan, and Prof. Joseph Manning (Yale University), Prof. Willy Clarysse and Prof. Mark Depauw (Catholic University Leuven) for consultation at various stages of the research. Our attendance at the papyrological congress was funded by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (no. 19320096) and Sasagawa Scientific Research Grant of the Japan Science Society (no. 22-115). We also thank Dr Jane Rowlandson, Dr Margaret Robb, and an anonymous reader for commenting on earlier drafts of this article and improving our English. We follow Shaw (2000) for the chronology of the dynastic period.

2 Although Akoris now should be written Hakoris, we use the former in this paper, because our publications use it throughout and in order to avoid confusion. For the excavations between 1981 and 1992, see Kawanishi (1995). For those from 1997 onwards, see the yearly reports by Kawanishi/Tsujimura (1998) to (2009) ; Kawanishi/Tsujimura/Hanasaka (2010).

3 See Kawanishi/Suto (2005). On OGIS 94, see Suto (2003) ; Kawanishi/Suto (2005) 199-204 ; SEG LIII 1931.

4 See Suto (2006) ; Kawanishi/Tsujimura (2006) 17-23 ; (2007) 18-23 ; (2008) 18-22 ; Kawanishi/Tsujimura/Hanasaka (2010) 17-23. Although publication of the final report is planned, its expected date is not fixed as our survey is still ongoing.

5 R. Takahashi, « Greek and Demotic Dipinti from a Ptolemaic Quarry in Middle Egypt », a paper delivered at the 25th International Congress of Papyrology (Ann Arbor 2007). The existence of the graffiti has been reported in Klemm/Klemm (1992) 91-100, esp. 94. The authors are especially interested in Zawiyat al-Sultan because of an unfinished colossus situated near the quarry. Their identification of the colossus with Amenhotep III (reign : c. 1390-1352 BC) is not tenable ; it should be dated to the Ptolemaic period due to the existence of Greek and demotic graffiti in its underground chambers. These graffiti are written in a manner similar to those found in the quarry discussed below, and thus constitute records of the process of quarrying the colossus from the bedrock. On the colossus and its graffiti, see Kawanishi/Tsujimura (2007) 20-23 ; Endo (2009).

6 Inventory numbers for the graffiti in these sections are provisional, and they may be renumbered in our final publication. For example, a Greek graffito discussed just below has two inventory numbers (L11 and L12) because we assigned them to its lines separately, not recognising that they actually compose a single graffito.

7 On the dating of this graffito, see below.

8 We thank Prof. Willy Clarysse and Dr Ruey-Lin Chang (University College London) for their help in reading the abbreviation of the months.

9 See Kawanishi/Tsujimura (2009) 17-21.

10 See Kawanisi/Tsujimura/Hanasaka (2010) 21-23.

11 See Thompson (1992a) ; (1992b) ; (1994). On the phenomenon of linguistic Hellenization, see, most recently, Muhs (2005) ; (2007) ; (2010).

12 See Manning (2009).