Tesserarius and Quadrarius

Village officials in fourth century Egypt

Little is known about either the tesserarius or the quadrarius, who appear in papyri from the end of the third century till the middle of the fourth century AD1. Most of the information is scattered in our papyrus sources. I hope in this paper to shed some light on these positions, and at the same time to draw attention to the understanding of some aspects of economic problems during this period. This paper will thus offer a discussion on the beginning and end of both positions, on the criteria for selection as well as duration of the mandate, and finally on the duties of both the tesserarius and quadrarius.

Tesserarius

The term tesserarius is of course of Latin origin, but it appears in Greek under the spellings τεccαράριοc, θεccαάριoc, τεccαλάριοc, θεccαλάριοc and τεcαλάριοc2. The difference in the spelling in papyri is attributed to individual techniques from one writer to another. For example, P. Cair. Isid. 54 contains a receipt addressed to Antonius Sarapammon, strategos of the Arsinoite nome, by Isidoros son of Palenios, and Doulos son of Timotheos, komarchs of Karanis, and Isidoros, tesserarius of the same village. This receipt was made in five copies, referred to as A, B, C, D, and E. Both A and C are in the same hand ; the title appears as θεccαάριοc In B, D, and E, the spelling is τεccαλάριοc.

The title tesserarius refers originally to a military officer who received and distributed watchwords from the commander on a tessera, i.e. a potsherd3. Originally a military position, it turns into a liturgy at the level of a village. The original meaning, however, does not clearly appear in every occurrence of the position, even when the term retains its military nature. Thus P. Oxy. I 43, ii, 21 contains military records giving an account of supplies, chiefly of fodder, provided to various troops and officers. There is no mention of either tessera or of a watchword.

Although the editors of P. Oxy. XII 1425 mentioned that the tesserarius was a village official, they did not decide if this position was a military or a civil one. Jouguet suggested in P. Thead. 32 that the tesserarius was known as a military officer, but that in Egypt he was a member of the civilian staff dealing with the military tax (annona)4. In Roger Bagnall’s opinion, the tesserarius was a village tax official5. From this and other information found in papyri, we will explain more about the duties of the tesserarius.

In papyri, the tesserarius holds his position alone, without sharing it with a colleague in the same place6. The village was his place of duty7. He was appointed – like others among village officials in the fourth century – by the praepositus, following a nomination by the komarch, who submitted a group of names to the praepositus to choose from ; only one person was eventually selected as tesserarius8. This is clear from P. Oxy. LXI 4128, which contains a declaration presented to the praepositus including a list of persons to act in liturgy ; the tesserarius was one of them.

P. Got. 6 mentions that, after the appointment of Aurelius Psenponouthos as tesserarius in Soknopaiou Nesos, he served for less than a year, that is the last five months of the Egyptian year9. As the nomination for this position took place on Pharmouthi 14 (= March 10) and not at the beginning of the Egyptian calendar, it is more probable that this was an exceptional case in the liturgical system, where the office of tesserarius was vacant and required the appointment of a new candidate. In Karanis, Aurelius Isidoros served as tesserarius in both Tybi and Epeiph of AD 31410. It may be assumed that the tesserarius held his office for a full year. Also, a tesserarius could hold his office more than once : Aurelius Arion in Theadelphia served as tesserarius in AD 307, and in the same village in AD 31211.

Since the nomination of the tesserarius came from the komarch, his position must be hierarchically inferior to the latter’s, regardless of whether the name of the tesserarius came before or after the komarch in the document. We thus sometimes find the name of a tesserarius after the name of the komarch, as in P. Cair. Isid. 54. On the other hand, in a receipt addressed to Antonius Sarapammon, strategos of the Arsinoite nome, by Isidoros son of Palenios, and Doulos son of Timotheos, komarchs of Karanis, and Isidoros, tesserarius of the same village, the writers acknowledge that they have received payment from the bankers who handle the government funds in the Arsinoite nome ; in the signatures of the officials, the name of the tesserarius Isidoros comes before the names of the komarchs. P. Cair. Isid. 128 is a receipt issued by the tesserarius, the komarchs and a demosios of Buto (Memphite nome) to Aurelius Isidoros as tesserarius of Karanis ; here the name of the tesserarius Isidoros comes before the names of the komarchs. The same is found in the signatures of the officials12.

It is clear from the papyri that the tesserarius worked as a representative of his village and handled many duties alone or jointly with other village officials, especially the komarch. In the village of Thmoinepsobthis (Oxyrhynchite nome), the tesserarius, together with the komarch, recommends two of the village inhabitants to the praepositus for work as sitologoi13.

In the village of Dositheon (Oxyrhynchite nome), in an official return addressed to the praepositus, a tesserarius alone and on his own responsibility chooses someone to act as a donkey-driver in Pelusium in connexion with the state transportation service ; he introduces this driver to the praepositus14.

In Buto, in a receipt issued by the tesserarius, the komarchs and a demosios of Buto to Aurelius Isidoros as tesserarius of Karanis, we learn that some individuals have absconded from Buto and taken refuge in Karanis. They were discovered by the commission from Buto and were formally surrendered by Isidoros as representative of Karanis. In return he was given this receipt against any additional claim against him or his village15.

A tesserarius together with the komarch, sends a return to the praepositus, under their own responsibility, with a list of names of persons who will act as tax collectors in the village of Senekeleon (Oxyrhynchite nome)16. A tesserarius also works together with the komarch of the village of Sepho in the Arsinoite nome and prepares a register of the village inhabitants in his area17. It is likely that this register was made in order to find suitable candidates for a liturgy18.

A tesserarius oversaw the delivery of supplies and funds, as well as the estimation of the amount of tax liability imposed on the village for which he was responsible. Aurelius Arion, tesserarius of Theadelphia, issues a receipt for the delivery of a load of barley to an ἀποδέκτηc κριθῆc19. Isidoros, tesserarius of Karanis, joins the komarchs in certifying to the strategos of the Arsinoite nome that they have received from the public bankers the price of clothing which they have delivered to the appropriate recipients for the vestis militaris20. In AD 324, Onnophris son of Pekusis, tesserarius working together with the komarch of the village of Herakleides in the Oxyrhynchite nome, acknowledges that they have received from a banker of public money, on the strategos’ order, an amount corresponding to the value of charcoal supplied to the public bath21.

In Karanis, Isidoros, tesserarius of Karanis, and Palemon, quadrarius of the same village, complain to the prefect of Egypt Iulius Iulianus about injustice being inflicted on the people of Karanis by Theodoros, the praepositus of the pagus, and by the komarchs of Karanis who are represented as acting in collusion with him22. In both P. Col. VII 139 and 141, a tesserarius was among some other officials in Karanis who acquired property. This property covered an area of between 12 and 48 arouras23.

In many cases, it is assumed that tesserarii could not write in Greek24. This appears for instance in P. Cair. Isid. 54, which Aurelius Ision wrote on behalf of other officials, including a tesserarius, who did not know how to write Greek.

From this overview of occurrences, we can conclude that the tesserarius in fourth-century Egypt was a village official. He was chosen in the first place to monitor the collection of taxes imposed on the village. In addition, some other duties in the village may go back to the military origin of the office. Although we do not have evidence that the tesserarius had any duty to control the komarch’s actions, it seem that in some cases a tesserarius could have made a complaint directly to the prefect, criticizing the actions of komarch25.

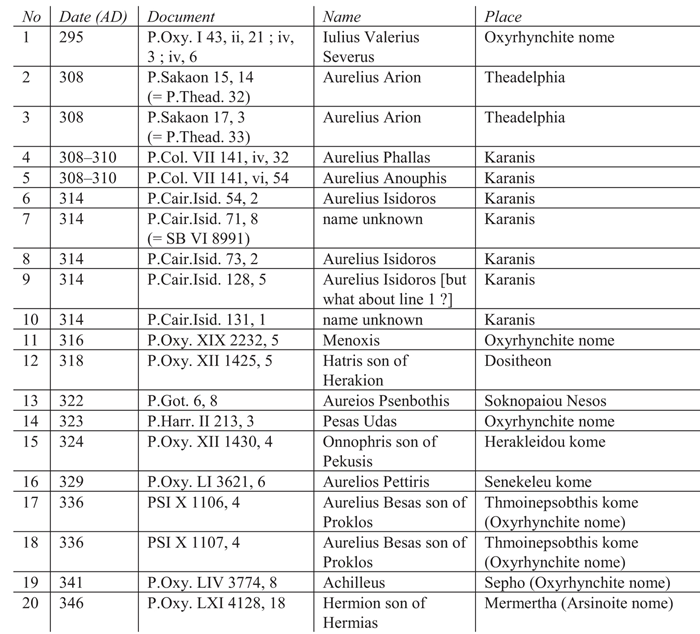

For the most part, our information on the tesserarius dates from the first half of the fourth century AD, which suggests that this position was the outcome of emperor Diocletian’s reforms. We lose track of the tesserarius in our papyri in AD 346 (P. Oxy. LXI 4128).

Quadrarius

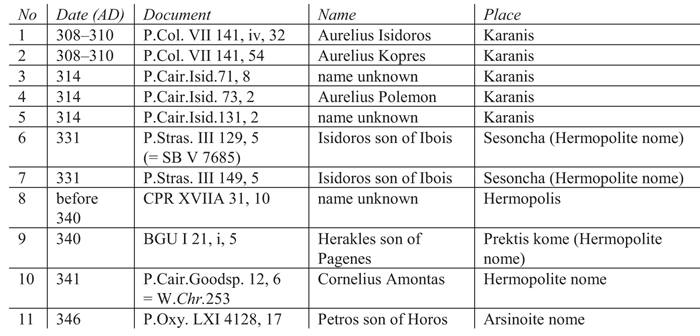

The second official we will discuss in this paper is the quadrarius (transliterated in Greek as κουαδράριοc). He appears less frequently in our documents than the tesserarius. In BGU I 21, the ephoros, two of the komarchs, and the quadrarius of the village Prektis in the Hermopolite nome send a report to the praepositus about tax collection in the village. From the same year, in P. Cair. Goodsp. 12, a statement of taxes sent to the praepositus by the ephoros, two of the komarchs, and the quadrarius, those officials acknowledge by oath the validity of the list of taxpayers.

This evidence shows that the quadrarius, like the tesserarius, was in the first place in charge of taxation at the village level. In both BGU I 21 and P. Cair. Goodsp. 12, the name of the quadrarius comes after that of the komarch, which could imply that the quadrarius held a position hierarchically lower than the komarch. Like the tesserarius, the office of the quadrarius could be entrusted to people who did not know how to write Greek26. Also, the quadrarius’ place of jurisdiction was the village. Since he appears in our documents in the first half of the fourth century, he was also presumably a product of the reforms of the Diocletian’s reforms in Egypt.

Bibliography

Bagnall, R. (1993), Egypt in Late Antiquity (Princeton).

Bagnall, R. (2003), « Property-Holdings of Liturgists in Fourth Century Karanis », BASP 15 (1978) 9-16 [= Later Roman Egypt : Society, Religion, Economy and Administration XXIII].

Berger, A. (1935), Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (Philadelphia).

Derda, T. (2001), « Pagi in the Arsinoites : A Status in the Administration of the Fayoum in the early Byzantine Period », JJP 31, 17-32.

Johnson, A., / West, L. (1949), Byzantine Egypt, Economic Studies (Princeton).

Lallemand, J. (1964), L’adminstration civile de l’Egypte de l’avènement de Diocletien à la création du diocèse (284-382) (Bruxelles).

Lewis, N. (1997), The Compulsory Public Services of Roman Egypt (2nd ed., Pap. Flor 28, Firenze).

Mason, H.J. (1974), Greek Terms for Roman Institutions (Am. Stud. Pap. 13, Toronto).

Mitthof, F. (2001), Anonna Militaris. Die Heeresversorgung im Spätantiken Ägypten (Pap. Flor. 32, Firenze).

Vandersleyen, C. (1962), Chronologie des préfets d’Egypte de 284 à 395 (Bruxelles).

Youtie, H.C. (1971), « Ἀγράμματοc : An Aspect of Greek Society in Egypt », HSCP 75, 161-176 [= Scriptiunculae II 611-627].

List of tesserarii

List of quadrarii

____________

1 Among papyri which include a mention of a tesserarius, only P. Oxy. I 43 dates from the third century (AD 295) ; the other occurrences date from the fourth century. A comprehensive list of occurrences of both offices is provided at the end of this paper.

2 See Mason (1974) s.v. tesserarius – τεccεράριοc For τεccαράριoc : P. Oxy. I 43 ; θεccαάριoc : P. Thead. 32 ; P. Cair. Isid. 54 ; τεccαλάριoc : P. Cair. Isid. 54 ; P. Cair. Isid. 128 ; P. Cair. Isid. 131 ; P. Oxy. LI 3621 ; P. Oxy. LXI 4128 ; θεccαλάριoc : P. Cair. Isid. 71 ; P. Cair. Isid. 54 ; τεcαλάριoc : P. Oxy. XII 1430.

3 See Berger (1935) s.v. tesserarius ; OLD s.v. tesserarius ; LSJ s.v. τεccαράριoc.

4 On annona in general, see Mitthof (2001).

5 See Bagnall (1993) 337.

6 See Lewis (1997) s.v. τεccεράριοc.

7 See Johnson (1949) 215 ; on the administration in general : Lallemand (1964) 131-134.

8 On the praepositus, see Derda (2001) 19.

9 P. Cair. Isid. 131.

10 See the list below.

11 P. Thead. 32 ; P. Thead. 33.

12 See also P. Oxy. XII 1430.

13 PSI X 1106.

14 P. Oxy. XII 1425.

15 P. Cair. Isid. 128.

16 P. Oxy. LI 3621.

17 P. Oxy. LIV 3774.

18 See P. Oxy. LIV 3774, introduction.

19 P. Thead. 32.

20 P. Cair. Isid. 54.

21 P. Oxy. XII 1430.

22 P. Cair. Isid. 73 ; P. Cair. Isid. 71 and 72 are notes for drawing up this petition. On the quadrarius, see below. The prefect Iulius Iulianus was in office for only one year, i.e. 314 ; see Vandersleyen (1962).

23 See Bagnall (2003) 16.

24 On ἀγράμματοι, see Youtie (1971) 162.

25 P. Cair. Isid. 73.

26 See above, n. 24.