A Roman veteran and his skilful administrator

Gemellus and Epagathus in light of unpublished papyri

During the excavation season 1898-99, B.P. Grenfell and A.S. Hunt discovered in a house in the Fayum village of Kasr el Banât, ancient Euhemeria, documents from a family archive associated with Lucius Bellenus Gemellus, a landowner and former legionary living in the Fayum at the end of the 1st and beginning of the 2nd century AD1. The archive consisted primarily of private letters, as well as several accounts, a couple of contracts, a handful of receipts and a petition. Of the extant papyri, currently estimated at over 80 in total, 25 have been published in full and 28 described, mainly in P.Fayum. A few documents mentioning Gemellus that were acquired on the antiquities market but are not part of the archive were published elsewhere2. The bulk of the archive is scattered among at least sixteen museums and libraries around the world3. In addition to these ca. 50 papyri, there are an estimated 33 unpublished fragmentary texts that are kept in Oxford4. With the kind permission of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri Management Committee, we plan to examine them in the coming months. The aim of our editorial team, which also includes George Bevan and Michel Cottier, is to edit or re-edit all documents from or closely related to the archive.

The Gemellus/Epagathus papyri document activities associated with the management of a number of properties belonging to Gemellus in the Fayum towns of Euhemeria itself, as well as Dionysias, Apias, Senthis, Psennophris, Psinachis, and Prophetes5; the extent of the holdings is one of several remarkable aspects of the archive. The primary players appearing in the documents are Gemellus’ administrator Epagathus (referred to as his παιδάριον in the loan contract SPP IV, pp. 116-117 [= P.Fay. 260 descr.], 5 and 32); at least 12 letters are addressed to Epagathus from Gemellus (Grenfell and Hunt were aware of 10)6. Gemellus’ son Sabinus is the recipient of perhaps 10 of his father’s extant letters (Grenfell and Hunt appear to have been aware of only 5)7. It could turn out that Sabinus received as much if not more correspondence from Gemellus than Epagathus did, and this is significant since it was previously believed that Epagathus was the predominant person associated with the letters. In addition to these texts, we have at least 4 letters from Sabinus to Epagathus (Grenfell and Hunt knew of only 2) and one from Sabinus to Gemellus, plus a few involving individuals about whom we know nothing except what we derive from the letter in question8. So far we have established that Gemellus sent 26 of the surviving letters9. The fact that a majority of the letters were authored by Gemellus has led many to believe that he did not occupy the house in which the archive was found, although he is thought to have owned it. Epagathus, the recipient of many of the letters, probably lived there and administered Gemellus’ various properties from there. Gemellus’ primary residence was apparently in Aphrodites Berenikes Polis in the Herakleidou Meris10.

From P.Fay. 91, a contract to work in an oil-press which was written in the year 99, we learn that Gemellus was born around 32 AD11. Nearly all extant documents date from the 90’s and the first decade of the second century. The earliest securely dated text is from September 11, 9412; the latest is a letter from Sabinus to Epagathus from the year 11413. Gemellus is last seen alive in November 11014. Following his death, his son Sabinus is believed to have taken over management of the estate, hence 110 represents the terminus post quem for business-related letters written by Sabinus15.

As for family connections we know that, in addition to Sabinus, Gemellus had a daughter named Gemella and a grandson who is referred to as the little one, ὁ μικρόc Depending on how we take the word ἀδελφόc, we could justifiably postulate three additional sons, Harpocration, Lycus, and one whose name is lost: Sabinus refers to each of these as «brother», but the word of course need not necessarily reflect blood ties16. In addition to these children and grandchildren, Gemellus had a «brother» (whether real or not) named Marcus Antonius Maximus who is addressed in a fragmentary letter17. The name of Gemellus’ wife does not survive.

Gemellus’ estate appears to have focused on the production of olives. In one document, we see that he employed a fairly large workforce (93 workers for one day) for the olive harvest18. This was, however, seasonal work, and it is unclear how large his regular staff was. His estate also consisted of livestock (oxen, donkeys, sheep and pigs), arable land and probably vineyards (see below), and he communicated often with Epagathus about managing its various units19. Yet, despite the complexity and extent of the estate, a surprisingly large number of letters concentrate on other matters, such as preparations for parties – the birthdays of Sabinus and Gemella – and dealings with officials20. It is interesting to see how Gemellus relies on his paidarion Epagathus to direct everyday business activities, such as the conclusion of work contracts, transport of animals, oversight of the olive harvest21. When it comes however to more official business, Gemellus looks to his son Sabinus, his favored envoy and the future heir to his estate: in P.Fay. 113 and 114, for example, he asks Sabinus to summon the pediophylax in order to evaluate some overgrown fields owned by a friend, and in P.Fay. 117 he directs him to send «gifts» of olives and fish to the royal scribe who is becoming the strategus’ deputy; P.Fay. 119, also addressed to Sabinus, alludes to some business with the strategus22. Gemellus thus appears to have been a savvy landowner, actively involved in the operations of his estate, supported by a trusted manager, and aware of the importance of currying the favor of officials23.

Deciphering the new Gemellus papyri can be very challenging. Most of the letters were penned by Gemellus when he was in his 60’s and 70’s. His advanced age is often cited to explain the unsteady, crabbed character of his well-known hand, a script that can pose remarkable difficulty especially when coupled with poor spelling and partially preserved letters, as it often is. Despite its crabbedness, however, the hand is controlled and clearly that of an experienced writer. Robert Daniel recently argued that the advanced age of a writer can sometimes be observed in his script, which could have been affected later in life by illness or some other kind of incapacitation24. While we unfortunately do not have letters from Gemellus’ earlier years that could be used for the purpose of comparison, we would not be surprised if a decline in Gemellus’ handwriting might have occurred over time, as it did in the case of the writer Daniel comments on. In addition to difficulties that can be attributed to Gemellus’ writing, many of the papyri are also badly preserved, and damage is particularly acute in the middle part of the letters where the text does not usually follow any formulas. Nevertheless we have so far been able to discover at least some issues that enrich our understanding of the whole archive. They can be divided into three main categories. The first one pertains to new issues we learn from the texts. For example, the papyri mention people related to Gemellus who are not known from other texts in the archive: Charmus, the flautist Didymas, Marcus Antonius Maximus who is addressed by Gemellus as «brother» and could be the same as in SPP XXII 178 recto, 6 (2nd cent.), Panetb-, Pantarkus, Protion and finally the son of Orsenuphis who, together with Heron, is known from other letters as an intimate friend of Gemellus and Epagathus25. Furthermore, we also receive new information about Gemellus’ estate. The mention of the vintage in P.Fay. 270, 6 reveals that Gemellus’ property possibly included vineyards: this fact was unknown from the published texts.

A second category of interesting issues arises from the new texts. The papyri mention names and subjects which we also find in other letters of the archive, sometimes adding new information to them and allowing new readings and hypotheses. So, for example, the well known Heron (cf. above) is often mentioned in the new texts, once together with Suchotes, perhaps the same person Gemellus did business with in P.Fay. 122, 4-5 and SPP IV, pp. 116-117 (= P.Fay. 260), 7 and 29, and with Orsenuphis, who occurs also in P.Fay. 265, 11-1226. The texts add some information about Heron: he turns out to have been a komogrammateus in the year 9527.

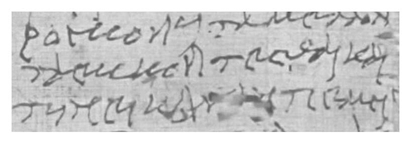

A very interesting subject addressed in many texts of the archive, which is to be found also in the new ones, concerns Gemellus’ requests for fish. These occur in three new papyri, whose context is not very clear because of the lacunas28. Nevertheless they allow at least one new reading in a papyrus already known: in P.Fay. 249, 17, Gemellus asks for εἰκθύα, i.e. ἰχθύα «Fischware» (cf. Preisigke, WB I, s.v. 2), and the same word probably recurs in the already published P.Fay. 114, 18 where the editors read τὴν εἰκθυίν, which they interprete as ἰχθύν. This reading cannot be right, because ἰχθύc is a masculine noun, and the image shows that a is indeed a better reading than ι. The letter is mostly missing in a lacuna and the only visible trace consists of a short vertical stroke whose top inclines to the left, as is typical of a in Gemellus’ writing, cf. e.g. P.Fay. 114, 17 ἐκκόπτεσθαι.

P.Fay. 114, 16-18

So, instead of εἰκθυίν we should read εἰκθύαν for ἰχθύαν as in P.Fay. 249, 17.

The third category of issues concerns palaeography. As is known, Gemellus, Sabinus and Epagathus were all able to write. Gemellus writes by himself all but one of the published letters addressed by him. Also, most of Sabinus’ letters whose images are available to us show that they are written in the same hand, which probably is his own29. To the hand of Epagathus belong probably the accounts found in the house and one hypographe, maybe also two contracts and two other papyri bought on the antiquities market30. Among the new texts there is one letter of Gemellus that was surely written by another hand31. There is also a letter by Sabinus to his father that is apparently not in Sabinus’ own hand32. Since the addressee is Gemellus, but the letter was found in Euhemeria, we should think either that Gemellus spent some time at Epagathus’ house – which is otherwise unattested, although not improbable – or that the letter is a draft written on behalf of Sabinus during one of his visits in Euhemeria33; in fact he was in Euhemeria at least in the years 100, maybe 103 and 10834. This hypothesis finds support in the fact that Sabinus writes about meeting Heron (1. 5), who, as already stated, was an intimate friend of Gemellus and Epagathus and lived in Euhemeria. As the handwriting in our opinion resembles that of Epagathus, one could imagine that Sabinus had the draft written by Epagathus and then perhaps copied the text in his own hand in order to send it to his father, or he never sent it and Epagathus kept the draft in his archive35. In any event, we probably have another instance of Epagathus’ hand among the texts of his archive.

Bibliography

Azzarello, G. (2007), «P.B.U.G. inv. 213: un nuovo frammento del rotolo omerico di Londra, Manchester, Washington e New York (= Mertens/Pack3 643) nella collezione di Giessen», APF 53, 97-143.

Azzarello, G. (2008), «Alla ricerca della “mano” di Epagathos», APF 54, 179-202.

Azzarello, G. (2009/2010), «Olives and More in P.Fay. 102: Complete Edition of an Account from the Gemellos’ Archive», Pap. Lup. 18/19, 5-36.

Bastianini, G. (1975), «Lista dei prefetti d’Egitto», ZPE 17, 263-328.

Daniel, R.W. (2008), «Palaeography and Gerontology: the Subscriptions of Hermas Son of Ptolemaios», ZPE 167, 151-152.

David, M./van Groningen, B.A. (1952), Papyrological Primer (3rd ed., Leiden).

Hohlwein, N. (1957), «Le vétéran Lucius Bellienus Gemellus, gentleman-farmer au Fayoum», Etudes de papyrologie 8, 69-91.

Montevecchi, O. (1950), . contratti di lavoro e di servizio nell’Egitto greco-romano e bizantino (Milano).

Olsson, B. (1925), Papyrusbriefe aus der frühesten Römerzeit (Uppsala).

Schubert, P. (2007), Philadelphie: un village égyptien en mutation entre le IIe et le IIIe siècle ap. J.-C. (Basel).

Smolders, R. (2006), in «Epagathos Estate Manager of Lucius Bellenus Gemellus», Papyrus Archives in Graeco-Roman Egypt, Trismegistos, <http://www.trismegistos.org/arch/archives/pdf/134.pdf>

White, J.L. (1986), Lightfrom Ancient Letters (Philadelphia).

____________

1 This project is at a preliminary stage and all findings should be regarded as provisional. For a general overview of the archive, see Smolders (2006) and Hohlwein (1957).

2 The published papyri are P.Fay. 91 = Sel. Pap. I 17 = Montevecchi (1950) no. 6 (Oct. 16, AD 99); 102 (103-104; complete edition in Azzarello [2009/2010]); 110 = Olsson (1925) no. 52 = White (1986) no. 95 (Sept. 11, 94); 111 = Olsson (1925) no. 53 = C.Pap. Hengstl 132 (maybe Sept. 13, 95, cf. Azzarello [2008] 181, n. 17); 112 = Olsson (1925) no. 54 = White (1986) no. 97 (May 21, 99); 113 = Olsson (1925) no. 55 = White (1986) no. 97 (before Dec. 14, 100); 114 = Olsson (1925) no. 56 = White (1986) no. 97 (Dec. 14, 100); 115 Olsson (1925) no. 57 (Aug. 21, 101); 116 = Olsson (1925) no. 58 (Dec. 2, 104); 117 = Feste 154 = Olsson (1925) no. 59 = White (1986) no. 98 (maybe Jan. 7, 108, cf. BL X 67); 118 = Feste 155 = Olsson (1925) no. 60 (Nov. 6, 110); 119 = Feste 87 = Olsson (1925) no. 61 (ca. 103, cf. BL IX 81); 120 = Olsson (1925) no. 62 (ca. 100); 121 = Olsson (1925) no. 62 = C.Pap. Hengstl 133 (after 110?, cf. Azzarello [2008] 180, n. 7); 122 = Olsson (1925) no. 62 (after 110?, cf. Azzarello [2008] 180, n. 7); 123 = C.Pap. Jud. II 431 = White (1986) no. 99 (after 110?, cf. BL IV 29, but see Azzarello [2008] 180, n. 7); 124 (2nd cent.); SB XVIII 13144 (= P.Fay. 246 descr.; maybe before Sept. 11, 94, cf. Azzarello [2008] 185); 13145 (= P.Fay. 247 descr.; after 110?, cf. Azzarello [2008] 186); SPP IV, pp. 116-117 (= P.Fay. 260 descr.; 109-110, cf. BL I 408); SPP IV, p. 118 (= P.Fay. 264 descr.; Aug. 26, 127, cf. BL XII 69); P.Oxf. 10 = David/Groningen (1952) no. 53 (Thead.; 98-102, cf. Azzarello [2008] 182, n. 20); P.Vindob. Tandem 14 (1st/2nd cent.); P.Laur. II 39 (early 2nd cent.; cf. Azzarello [2008] 191-192); maybe the texts written by hand 2 in P.Lond. Lit. 6 + P.Ryl. III 540 + P.Wash. Libr. of Congr. Inv. 4082 B + P.Pierpont Morgan Libr. Inv. M662B (6b) + (27k) + P.B.U.G. Inv. 213 (Arsinoite; late 1st/2nd cent.; cf. Azzarello [2007]). The descripta are: P.Fay. 248-250 (ca. 100); 251 (100-103, cf. Bastianini [1975] 279); 252-253 (ca. 100; complete edition of 253 is forthcoming); 254 (March 27-April 25, 104); 255 (ca. 100); 256 (Oct. 4, 113 or 132); 257 (ca. 100); 258 (124-125); 259 (81-96); 261 (ca. 100); 262 (June 20, 104); 263 (ca. 2nd cent.); 265 (ca. 100); 266 (Dec. 10, 95: Grenfell and Hunt appear to have been unaware of this date); 267 (ca. 100); 268 (98-110?: Grenfell and Hunt appear to have been unaware of this date); 269 (Oct. 22, 96 or Oct. 23, 97: Grenfell and Hunt appear to have been unaware of this date); 270-275 (ca. 100); 276 (114: Grenfell and Hunt appear to have been unaware of this date); 277 (ca. 100). These texts include the 11 papyri found in the house that are of uncertain relation to the Gemellus/Epagathus texts, cf. Smolders (2006) 1. See the BL for corrections and suggestions that have been proposed for individual texts.

3 We are grateful to all the institutions that have sent us images and/or made them available on-line, in particular to members of the Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS) (see now http://www.papyri.info).

4 Smolders (2006) 3.

5 Dionysias: P.Fay. 102, col. II 20; 110, 16; 111, 12, 15-16; 112, 15; 113, 5; 114, 7; 118, 10-11; 248; 251; 257. Apias: the olives account in P.Fay. 102, col. II 1; 112, 8-9; 120, 8, 11; SPP IV, p. 118 (= P.Fay. 264 descr.), 3. Senthis: the olives account in P.Fay. 102, col. II 12; 111, 22-23; 112, 19 (for a different view, see BL VIII 122, 122-123). Psennophris: P.Fay. 118, 19-20, 22. Psinachis: P.Fay. 119, 9, 33; 248; 257 and, according to our forthcoming edition, 269, 11. Prophetes: the olives account in P.Fay. 102, col. I (a) 3; 111, 26; P.Laur. II 39, 7-8.

6 P.Fay. 110-112, 115-116, 120, 248-249, 254, 259, 266, 267. P.Fay. 265 and 269 were addressed to either Epagathus or Sabinus. For discussion of P.Fay. 118, which is generally thought to have been sent to Epagathus, see below, n. 22.

7 P.Fay. 113-114, 117, 118? (see below, n. 22), 119, 268, 270-273.

8 P.Fay. 122, 250, 275-276 were sent by Sabinus to Epagathus, and P.Fay. 261 from Sabinus to Gemellus.

9 P.Fay. 110-120, 248-249, 252, 254-255, 259, 265-273.

10 In several letters, Gemellus requests things and people to be sent to him in the city (see e.g. P.Fay. 114, 5-6; 116, 6-7; 118, 17-18) and in a couple letters identifies the city as Aphrodites Berenikes Polis (P.Fay. 115, 16-17; 120, 6-7 and, according to our forthcoming edition, 270, 3).

11 In line 12 he is said to be around 67 years old.

12 P.Fay. 110.

13 P.Fay. 276, cf. above, n. 2.

14 P.Fay. 118.

15 See e.g. P.Fay. 121 and 275; cf. also Azzarello (2008) 180, n. 7.

16 P.Fay. 123, 2-3 and 25-27.

17 P.Fay. 252.

18 The olives account in P.Fay. 102, especially col. II, 4-6.

19 For references to oxen, see P.Fay. 112, 8; 115, 15-16; P.Fay. 253 (cf. above, n. 2) and, according to our forthcoming edition, P.Fay. 271, 9, 12, 14 and 16. Donkeys are mentioned in P.Fay. 266, 19 (ὄνoc, according to our forthcoming edition); 111, 6-7 (τὰ ἐργατικὰ κτήνη, which the editors interpret as «donkeys or horses»; cf. also P.Fay. 249, 3-4 according to our forthcoming edition). For sheep, consult P.Fay. 110, 13. For pigs, see P.Fay. 111, 3-5, where Gemellus criticizes Epagathus for the death of two pigs; cf. also P.Fay. 115, 4 and 7.

20 Sabinus’ birthday celebration is mentioned in P.Fay. 115; cf. also P.Fay. 111 with Azzarello (2008) 181, n. 17; Gemella’s in P.Fay. 114 and 119.

21 Epagathus acknowledges receipt of money owed in a work contract (P.Fay. 91, 48-51). The transport of animals is a concern in P.Fay. 111, 3-10. Oversight of the olive harvest is sought in, e.g., P. Fay. 112.

22 P.Fay. 118 also mentions strategi. The name of the recipient of the letter does not survive, but editors have thought that it was addressed to Epagathus. We conjecture on the contrary that Sabinus may have been the actual recipient – compare the expressions in lines 23-24; 25-26 and in P.Fay. 119, 23-24; 25-27.

23 Gemellus’ situation may be compared with the case of Marcus Iulius Casianus, cf. Schubert (2007) 89-96, esp. 90; see also the case of the veteran Ammonianos, Schubert (2007) 49-54.

24 Daniel (2008).

25 Charmus appears in P.Fay. 273, 14; the flautist Didymas in P.Fay. 272, 10-11; Marcus Antonius Maximus who is addressed by Gemellus as «brother» in P.Fay. 252, 2-3; Panetb- in P.Fay. 269, 22; Pantarkus in P.Fay. 268, 31-32 and 270, 4; Protion in P.Fay. 265, 4; and the son of Orsenuphis in P.Fay. 272, 4-5; cf. P.Fay. 112, 22 and 115, 10-11, and also below.

26 P.Fay. 261, 5 and 271, 15-16; he is mentioned together with Suchotes in P.Fay. 266, 16-17 and with Orsenuphis in P.Fay. 266, 16.

27 P.Fay. 266, 16-17 (cf. above, n. 2); cf. also P.Fay. 271, 15-16.

28 P.Fay. 249, 17; 266, 7; 267, 2-3.

29 P.Fay. 121-122; 250 and 274-277; for 261, see below.

30 Cf. Azzarello (2008).

31 P.Fay. 252.

32 P.Fay. 261.

33 Cf. also Smolders (2006) 4, n. 3.

34 That he was there in 100 we know from P.Fay. 113 and 114; for possible visits in 103 and 108, see P.Fay. 119 and 117 (with n. 2 above).

35 See especially SB XVIII 13144; 13145 and P.Fay. 253 (cf. above, n. 2); cf. Azzarello (2008) 184-189.