Wild papyri in the Roca-Puig collection

P.Monts.Roca inv. 46 and P.Monts.Roca inv. 47, both assigned to the third century BC, are the oldest Homer papyri preserved in the two Catalan collections. They were published by Ramon Roca-Puig in the seventies of the last century, and they are currently the subject of a re-edition by myself, to appear soon together with other items of the Montserrat collection2.

After Stephanie West’s work on the Ptolemaic papyri of Homer, many other Ptolemaic papyri have been published3. The following table lists a number of Homeric papyri from the Ptolemaic period ; it could be much extended, and I have deliberately omitted many papyri from the first cen-tury BC, as well as those dated between the first century BC and AD, since they are closer to the Roman period.

| reference | Homeric passages | date |

| P.Sorb. I 4 | Il. 12, 228-229, 231-232, 234, 238, 246-265, with the omission of 262 | III BC |

| P.Sorb. inv. 2302 = Boyaval (1967) 61-654 | Il. 6, 280-292, with three plus-verses : 280a, 288a, 288b | III BC |

| P.Sorb. inv. 2303 = Boyaval (1967) 65-695 | Il. 17, 566-578, also containing plus-verses : 574a, 574b, 578a, 578b | III BC |

| PSI XV 1463 | Od. 22, 420-434, with lines 425-427 and 430 omitted | III BC |

| P.Strasb. inv. WG 2342-2344 = Huys (1989) | Il. 19, 325-329 | III BC |

| BKT IX 119 | Il. 7, 183-195 | III/II BC |

| P. Schøyen inv. MS 5094 = Montserrat (1993) | Il. 17, 637-644, 679-685, 687-689 | mid-III BC |

| BKT IX 146 | Il. 8, 3-17 [6 or 7 omitted] | III/II BC |

| P.Vat.inv. G 64 | Il. 16, 32-34, 40-42, 50-59, 68-81 | III/II BC |

| P. Köln VIII 333 | Il. 23, 659-668 and 718-727, with the omission of 665-666 | III/II BC |

| P. Bodmer inv. 49 = Hurst (1986) | Od. 9, 456-488, 526-530, 537-556, with a plus-verse 537a ; 10, 188-214, with 192 omitted and 199a as a plus-verse | III/II BC |

| P. Leuven Univ. Bibl. inv. 1987.01 = Huys (1988) | Od. 10, 185-195 | III/II BC |

| P.Col. VIII 200 | Od. 12, 384-390 | III/II BC |

| P.Sorb. I 2 | Il. 2, 127-140 | II BC |

| BKT IX 128 | Od. 22, 193-217, 235-252 | II BC |

| P.Laur. inv. III/269 E = Messeri Savorelli/Pintaudi (1997) 171 | Od. 12, 20-24 | II BC |

| P. Schøyen I 5 | Od. 11. 590-605 | II BC |

| P. Schøyen I 6 | Od. 12, 9-14, 16a-27, 41-46 (with numerous extra lines : 10a, 11a-11b, 16a, 20a, 46a-46c) | II BC |

| P.Mich. inv. 6972 = Edwards (1984) | Il. 10, 421-434, 445-460 | mid-II BC |

| P.Gen. II 82 | Od. 21, 146 (?) – 165 | mid-II BC |

| P. Chicago Newberry Libr. inv. Greek Ms. 1 (ORMS 55)r = Torallas Tovar/Worp (2009) | Il. 21, 567-581 | late II/early I BC |

| P. Schøyen I 4 | Il. 16, 2-15, 31-37, 39-43, 46-61, 75-92 | I BC |

| P. Qasr Ibrîm 1 | Il. 8, 273-276 | I BC |

| P. Qasr Ibrîm 2 | Od. 2, 72-100, 107-108, 110-111, 120, 122-125 | I BC |

| P. Qasr Ibrîm 3 | Od. 5, 122-133, 135-141, 165-171 | I BC |

What follows here is the result of the philological study of the texts transmitted by the two Montserrat papyri, which share the same peculiarities present in many other Ptolemaic papyri, as noted above, in close connection with their production standards. Indeed, although the bearing of such aspects on the quality of the text is widely acknowledged in the case of literary papyri from the Roman period, Ptolemaic papyri, perhaps because of their scarcity, tend to be treated as a whole, with little discrimination in terms of their bibliological characteristics. For the text of our papyri, I will follow Roca-Puig’s editions, unless otherwise stated, and for the so-called vulgate text, I will use West’s edition of the Iliad and Von der Mühll’s for the Odyssey6.

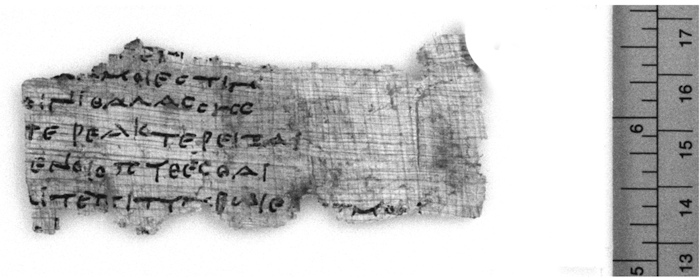

P.Monts.Roca inv. 46 contains the ends of lines of Od. 11, 73-78. Although it is a small fragment (w 8,3 x h 3,5 cm), a generous right-hand margin has been preserved, and other features point towards a copy produced with some care : it is written along the fibres, the back is blank and letters, even if not formally executed, and certainly not keeping to well defined upper and lower notional lines, are rather spaced and only very occasionally touch each other7. Like other early Homer papyri, P.Monts.Roca inv. 46 presents some divergences from the text transmitted by the medieval manuscripts and papyri copied after 150 BC approximately ; after that date, the text was so regularly standardised that an abstraction of all these textual items is designated as the Homeric vulgate. Among those divergences, the presence of the so-called plus-verses, or verses that we do not find in the vulgate tradition at a particular point of the poem – but are in most cases to be found somewhere else in the epic tradition – is very characteristic of early Ptolemaic papyri8. Indeed, it is mainly the high frequency and number of these plus-verses in those papyri that has earned them the name of eccentric or wild papyri. P.Monts.Roca inv. 46 has such a plusverse in 75 a :

75 сῆμά τέ μοι χεῦαι πολιῆс ἐπὶ ]θινὶ θαλάссηс

75a κ]τέρεα κτερεΐξαι

As stated above, the papyrus preserves only the line-ends, and we cannot know what the first hemistich of the line was ; the second, however, appears in Od. 1, 291, also in a funerary context :

νοсτήсαс δὴ ἔπειτα φίλην ἐc πατρίδα γαῖαν

291 сῆμά τέ oἱ χεῦαι καὶ ἐπὶ κτέρεα κτερεΐξαι

πολλὰ μάλ’, ὅссα ἔοικε, καὶ ἀνέρι μητέρα δοῦναι.

In the passage in our papyrus, Elpenor asks Odysseus to perform the funerary rites for him : in verse 75, he is to heap up a mound on the shore of the sea. In Od. 1, 291, Athena orders Telemachos to return home and pay his father the funerary rites if he hears that he has died, again heaping up a mound and making the due offerings on it (291). Roca-Puig (1973) 113 suggested the first half of 292 as the first hemistich of 75a : πολλὰ μάλ’, ὅссα ἔοικε, ἐπὶ κ]τέρεα κτερεΐξαι ; but this would cause a hiatus and a somehow odd syntax, since there would be no connector between κτερεΐξαι and the previous χεῦαι. As Roca himself says, « on pourrait multiplier les hypothèses, toutes aussi incertaines » ; and in fact, it might even be possible that the first half of line 75a should be the same as 291, and that we should have a different first hemistich for 75. In any case, our line is not easily explained as a simple case of interpolation, as happens with most plus-verses. It is also of interest that the verse, as it appears in Od. 1, 291, is the object of philological discussion, as revealed by the scholia9. Thus the scholion attributed to Aristonicus :

χεῦcαι] τὸ ἀπαρέμφατον ἀντὶ τοῦ προсτακτικοῦ. H

Or this one offering an explanation for the infinitive construction :

χεῦcaι] γρ. δὲ oὕτωс ‘χεῦcaι’ καὶ ‘κτερεΐξαι’, ἀπαρέμφατα δεχόμενα τὸ προαιρετικὸν ῥῆμα ἀπ’ ἔξω˙ θέληсόν τι ποιῆсαι ; χεῦcaι. καὶ θέληсόν τι ποιῆсαι ; κτερεΐξαι. H

Eustathius also comments on the syntax of the phrase10 :

ὅτι τὸ, κτέρεα κτερεΐξαι, οὐ μόνον ἐτυμoλoγικῶc ἔχει, ἀλλὰ καὶ Αττικόν ἐсτι cχῆμα сυνεκφωνουμένου ῥήματoc καὶ cυcτoίχoυ ὀνόμaτoc (...) ἰсτέον δὲ ὅτι ταυτολογῶν ὁ ποιητήс, οὐ γὰρ ὀκνεῖ καὶ τοῦτο καιρίωс ποιεῖν, ἀνωτέρω μὲν ἔφη ἕδνα πολλὰ μάλα ὅсαἔoικεν. ἐνταῦθα δέ, κτέρεα πολλὰ μάλα ὅсα ἔοικεν.

The phrase also appears in the same author as an example of etymology to parallel Od. 1, 325 : τὸ δὲ ἀοιδὸс ἄειδε, τρόπoс καὶ αὐτὸ ἐτυμoλoγίαс ἐсτὶν ὡс καὶ τὸ κτέρεα κτερεΐξαι11.

Whatever stood as the first hemistich of the verse might have had an effect on the syntax of the following line, for сῆμα in line 75 is now separated from its genitive ἀνδρὸс δυсτήνοιο : our papyrus shows the genitive ending -οιο in place of the dative plural -οιсι of the participle in the vulgate version (ἐссoμένoιсι πυθέсθαι) : thus, instead of vulgate

сῆμά τέ μοι χεῦαι πολιῆс ἐπὶ θινὶ θαλάссηс,

76 ἀνδρὸс δυсτὴνoιo, καὶ ἐссομένοιсι πυθέсθαι

we have

сῆμά τέ μοι χεῦαι πολιῆс ἐπὶ ]θινὶ θαλάссηс

κ]τέρεα κτερεΐξαι

ἀνδρὸс δυсτήνοιο, καὶ ἐссομ]ένοιο πυθέсθαι

The genitive before πυθέсθαι might be that of a different word. Roca-Puig (1973) 113 adduces, as an instance, Od. 8, 12 ὄφρα ξείνοιο πύθηсθε, though better fitting our context would be Il. 19, 322 οὐδ’ εἴ κεν τοῦ πατρὸс ἀποφθιμένοιο πυθοίμην or Il. 19, 337 λυγρήν ἀγγελίην, ὅτ’ ἀποφθιμένοιο πύθηται. The possibility that the scribe was misled by the previous genitive ending in δυсτήνοιο must, however, remain open, even if the scribe does not seem to have been careless. In fact, the following line (77), exceedingly protruding to the right for no apparent reason, seems to be reflecting some kind of correction, which could make us think of some sort of διόρθωсιс as yet another sign of the quality of the copy12. On the other hand, the fact that εсτιν at the end of 74 carries the ephelcistic ν – although the following line begins with a consonant – is completely consistent with the normal practice in Ptolemaic papyri and should not be regarded as any kind of error13.

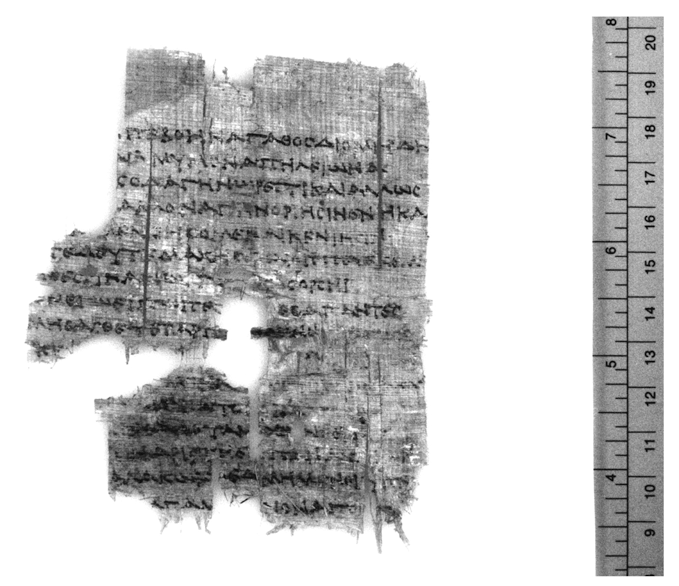

Somehow different is the impression we have from our other papyrus, P.Monts.Roca inv. 47. It has partially preserved the end of Il. 9, 696 – 10, 3. Its generally untidy appearance is partly due to the fact that it comes from cartonnage, but some other features may reveal lower production standards than those noticed for P.Monts.Roca inv. 46 : letters are less spaced here than they are there, more frequently touching each other, and the same applies to the lines. Margins, at least to the extent that they are preserved, are narrower than those in P.Monts.Roca inv. 4614.

As for atypical features in P.Monts.Roca inv. 47, we find no plus-verse in the papyrus, but we have several minus-verses, i.e. lines transmitted by the vulgate version and missing in our text. The first of them is 697, the initial line of Diomedes’ speech, where he addresses Agamemnon. What the meaning of this absence might be will be dealt with shortly, when discussing minus-verse 709. For now, let us focus on other textual divergences of a different nature : in 701, we have εηсομεν αι κεν ιηсιν instead of ἐάсομεν ἤ κεν ἴῃсιν : the scribe has regularised the future form according to the normal paradigm of the contracted verbs in -άω (lengthening the thematic vowel and closing it into an eta )15. On the other hand, very probably misled both by the phonetics and the frequency of the sequence αἴ κέ in the Homeric epics, he has written αι κεν in the place of ἤ κεν, although we have no conditional, but a disjunctive conjunction here.

Likewise, in the following line we find η κε μενη το]τε δ ουτε μαχηсεται οπποτε κεν [μιν instead of ἦ κε μένῃ. τότε δ’ αὖτε μαχήсεται ὁππότε κέν μιν. The mistake in this case seems to have been caused by the general meaning in Diomedes’ speech : « You should not have tried to persuade him to fight, for this has made him even more arrogant. Let us leave him alone, whether he leaves or stays, for he won’t fight, anyway » instead of the manuscripts’ text « for he’ll come back to fight when his soul... ».

The divergences discussed so far, therefore, point in the direction of a vulgarisation of the text, as the more complex question of the minus-lines seems to indicate : verses 697, 706 and 709 are missing from the text ; West’s apparatus does not record that any vulgate manuscript has dropped them.

Before discussing 697 and 709, let us consider 706. Eustathius comments on the construction of the participle τεταρπόμενοι : καὶ ὅτι τὸ τεταρπόμενοι сυvήθωс γενικῇ сυντέτακται, ληφθὲν ἀντὶ τοῦ κορεcθέvτεc, ἢ καὶ ἄλλωс, κατὰ ἔλλειψιν, ἵνα λέγῃ ὅτι τερφθέντεс διὰ τοῦ φαγεῖν καὶ πιεῖν. ἐκ περιссοῦ δὲ μετὰ τὸ τεταρπόμενοι κεῖται τὸ φίλον ἦτορ. καὶ αὐτοῦ γὰρ ἄνευ ἐντελὴс ἡ ἔννοια16.

Although the papyrus surface is badly abraded at this point, we seem to have the remains of the « unnecessary » – ἐκ περιссοῦ in Eustathius’ words – φίλον ἦτορ after the participle, but the following line is missing : the genitive commented on by Eustatius has disappeared, leaving the construction κατὰ ἔλλειψιν, and so has the formulaic τὸ γὰρ μένοс ἐсτὶ καὶ ἀλκή. As Stephanie West points out, it is difficult to decide whether the line has been dropped from our scribe’s text, or whether it has been introduced in the vulgate version, but, to quote her words, « where the line is inoffensive and there is no apparent reason why anyone should have excised it, it should probably be rejected »17.

The absence of 697 and 709 also results in a simpler text : the scholia record the rarity of the presence of a singular form after the last lines in Diomedes’ speech, which seem to be addressed to the whole community of warriors. Thus the scholion attributed to Aristonicus comments at this point18 : <ὀτρύνων καὶ δ’ αὐτὸс <ἐνὶ πρώτοιсι μάχεcθαι> : > ὅτι τὸν λόγον τοῦτον ἀκήκοεν κατὰ τὸ сιωπώμενον ὁ Ἀχιλλεύс· διό φηсιν οὐ γάρ Τυδείδεω Διομήδεοс ἐν παλάμῃсι | μαίνεται ἐγχείη (Π 74-75). καὶ ὅτι τῷ ἀπαρεμφάτῳ ἀντὶ τοῦ προсτακτικοῦ κέχρηται. καὶ ὅτι τῇ ἐχομένῃ Ἀγαμέμνων ἀριсτεύει. A

Similarly the scholion 9, 709b ex. has : <καὶ δ’ αὐτὸс ἐνὶ πρώτοιсι μάχεсθαι :> сτρατηγικῶс, πρὸс τὸ καταπλῆξαι τοὺс ἐναντίουс τῷ πρόθυμον γενέсθαι τὸν βαсιλέα. b(BCE3E4)T.

Eustathius also needs to explain the speech at this point, emphasizing that the infinitives are in place of a second person singular imperative19 : ἡ δὲ τοῦ Διομήδουс ἐνταῦθα πρὸс τὸν βαсιλέα φράсιс περὶ παρατάξεωс τοιαύτη · αὐτὰρ ἐπεί κε φανῇ καλὴ ῥοδοδάκτυλοс Ἠώс, καρπαλίμωс πρὸ νεῶν ἐχέμεν, ἤγουν ἔχε, λαόν τε καὶ ἵππουс ὀτρύνων, καὶ δ’αὐτὸс ἐνὶ πρώτοιсι μάχεсθαι, ὅ ἐсτι μάχου.

Notice how he explicitly says that the speech is directed towards Agamemnon (πρὸс τὸν βαсιλέα φράсιс). Likewise, the following scholion insists on the same fact : 9, 708-709 <πρὸ νεῶν ἐχέμεν <λαόν τε καὶ ἵππουс | ὀτρύνων> : ἀπὸ τοῦ κοιμήсαсθε (I 705) πληθυντικοῦ ἐπὶ τὸ ἐνικὸν μετῆλθε сχηματίζων · ἐπὶ γὰρ Ἀγαμέμνονα μετήγαγε τὸν λόγον. b(BCE3E4)T. And similarly 9, 708.1 ex. <<ἐχέμεν :>> ἀντὶ τοῦ ἔχε сύ, ὦ βαсιλεῦ δηλονότι. Til

If so many explanations were required, it means that there was quite a difficulty in understanding this apparent change of addressee in the speech, which our scribe may have tried to eliminate by getting rid of both the initial apostrophe to Agamemnon (697) and the last line of the speech, where the singular form reappeared once the speech had shifted clearly to the whole of the Greek army. Once again we thus have a simplification of the text.

The line following 708, however, is not 710. In fact, the remains of the two lines following 708 are not consistent with any of the verses left from this point down to the end of the book. The third one can be safely identified with the first line of book 10. Whether or not there was a mark, such as a paragraphos, to mark the end of book 9 is not for us to know20 : the left-hand margin, where it would have appeared, is not preserved. It would not be surprising after all that there was no mark at all21 ; what is surprising is to find a different end for book 9 altogether. Regardless of the reconstruction of the two lines following 708, it seems clear that our papyrus did not finish the book with the warriors retiring to sleep, quite a typical scene to be found at the end of other books : thus Il. 7, and Od. 16, 18 but also 5, 7 and 14, where Odysseus lies down to sleep, and 19, where Penelope falls asleep.

The second line after 708, which we could call 708b, reads ]с̣ι̣ν̣ε̣αδ̣οταμυθ[ο]νε̣ειπ̣[ ; Roca edited it as πα]с̣ι̣ν̣ εαδοτα μυθον εειπ̣ε̣ν̣22. It is therefore clear that Diomedes’ speech ends here, or in the previous line, and that immediately afterwards we are presented with the scene of the sleepless Agamemnon23. This fact seems to contradict the thesis that book division as we know it was original, that is, as Minna Skafte Jensen maintains, « the poet’s work »24 ; it also undermines the idea that book-ends such as we know them were already well established in the Ptolemaic period25.

At least our scribe does not seem to have been familiar with it : if indeed it was a well established fact that the end of book 9 occurred after our line 713, this particular point in the narrative would be a most unlikely one for the scribe to tamper with. The papyrus seems to reflect a continuous recitation, with no particular stop at this point. We have seen how the text has been simplified in terms of awkward forms and lines ; but, because these final lines do not seem to be problematic, we have no reason to think that he may have eliminated them26. Most critics agree that the division of the Homeric epics in 24 books was not original27 ; especially in the case of the Odyssey, where the resulting books are in some cases much shorter than in the Iliad, it is not always easy to see why a particular point in the narrative was chosen to end a book28. It is therefore not unnatural to think that such points may have been reinforced by means of adding a typical closing scene such as the men retiring to their tents in order to round off the end of the book29. Although our scribe did not produce an utterly careless copy, he certainly does not seem to have been very worried about meeting the highest production standards ; rather, we seem to have a copy for private recitation, where no philological refinements would be expected, not to mention, very probably, a book-division system that, to judge from the evidence of our papyrus, had not yet become standard in the third century BC, just like the text itself.

Bibliography

Andersen, Ø. (1999), « Dividing Homer. When and How Were the Iliad and the Odyssey Divided into Songs ? Comments », SO 74, 35-40.

Bolling, G.M. (1945), « Movable nu at the End of Homeric Verses », CPh 40, 181-184.

Boyaval, B. (1967), « Deux papyrus de l’Iliade (P.Sorb. inv. 2.302 et 2.303) », BIFAO 65, 57-69.

Cavallo, G./Maehler, H. (2008), Hellenistic Bookhands (Berlin/New York).

De Jong, I.J.F. (1999), « Dividing Homer. When and How were the Iliad and the Odyssey Divided into Songs ? Comments », SO 74, 58-63.

Dindorf, W. (1855), Scholia Graeca in Homeri Odysseam (Oxford, repr. 1962).

Edwards, A.T. (1984), « P.Mich. 6972 : An Eccentric Papyrus Text of Iliad K 421-34, 445-60 », ZPE 56, 11-15.

Erbse, H. (1969-1988), Scholia Graeca in Homeri Iliadem (scholia vetera) (Berlin).

Hainsworth, B. (1993), The Iliad : A Commentary. Vol. III : books 9-12 (Cambridge).

Heiden, B. (1998), « The Placement of Book Divisions in the Iliad », JHS 118, 68-81.

Hurst, A. (1986), « Papyrus Bodmer 49 : Odyssée 9, 455-488 et 526-556 ; 10, 188-215 », Museum Helveticum 43, 221-230.

Huys, M. (1988), « A Ptolemaic Odyssey Papyrus in Louvain (P. Leuven 1987.01 : κ 185-195) », Ancient Society 19, 61-70.

Huys, M. (1989), « Euripides, Alexandros fr. 46 Snell unmasked as Ilias T 325-329 », ZPE 79, 261-265.

Jensen, M.S. (1999), « Dividing Homer. When and How Were the Iliad and the Odyssey Divided into Songs ? Report », SO 74, 5-34.

Messeri Savorelli, G./Pintaudi, R. (1997), « Frammenti di rotoli letterari laurenziani », ZPE 115, 171-177.

Montserrat, D. (1993), « A Ptolemaic Papyrus of Iliad 17 », BICS 38, 55-58.

Nünlist, R. (2006), « A Neglected Testimonium on the Homeric Book-Division », ZPE 157, 47-49.

Pontani, F. (2007), Scholia Graeca in Odysseam I. Scholia ad libros a-ß (Roma).

Roca-Puig, R. (1972), Homer. Fragment de l’Odissea, 11, 73-78. Papir de Barcelona, inv. no. 46 (Barcelona).

Roca-Puig, R. (1973), « Un fragment de l’Odyssée du IIIe siecle avant J.-C. (P. Barc. inv. no. 46) », CE 48, 109-113.

Roca-Puig, R. (1976), Homer. Fragment de la Ilíada. 9, 696 1 0, 3. Papir de Barcelona, Inv. número 47 (Barcelona).

Roca-Puig, R. (1998), « Homer. Fragment de la Ilíada. 9, 696 – 10, 3. Segona edició », in Balasch, M. (ed.), Ramon Roca-Puig, i la ciència dels papirs (Lleida) 5-11.

Schironi, F. (2010), To Mega Biblion. Book-ends, End-titles, and Coronides in Papyri with Hexametric Poetry (Durham, North Carolina).

Torallas Tovar, S./Worp, K.A. (2009), « A Fragment of Homer, Iliad 21 in the Newberry Library, Chicago », BASP 46, 11-14.

Von der Mühll, P. (1945), Homeri Odyssea (Editiones helveticae, series Graeca 4, Basel, repr. Stuttgart 1971).

West, M.L. (1998-2000), Homeri Ilias (Stuttgart/München).

West, M.L./West, S. (1999), « Dividing Homer. When and How Were the Iliad and the Odyssey Divided into Songs ? Comments », SO 74, 68-73.

West, S. (1967), The Ptolemaic papyri of Homer (Pap. Colon. 8, Köln/Opladen).

____________

1 The present contribution has been elaborated in the framework of the Papyrological Project FFI2009-11288, financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for the period 2010-2012.

2 For the first papyrus, see Roca-Puig (1972), re-edited by Roca-Puig (1973) ; for the second, Roca-Puig (1976), re-edited by Roca-Puig (1998). Those texts will be re-edited in P.Monts.Roca IV, forthcoming.

3 See West (1967).

4 Published shortly before West (1967).

5 Published shortly before West (1967).

6 See M.L. West (1998-2000) ; Von der Mühll (1945).

7 On the vulgate text, see below. Although, according to production standards in the Roman period, we would expect a higher degree of formality from a bookhand, examples of this kind of bookhand from the mid-third century BC show irregularities similar to those in our papyrus ; see especially Cavallo/Maehler (2008) nos. 1 [P. Petrie II 49(c)] and 12 [P. Heid. 178]. Our papyrus is catalogued and can be seen at <http://www.dvctvs.upf.edu/catalogo/ductus.php?operacion=introduce&ver=1&nume=353>.

8 On the nature of these plus-verses, see S. West (1967) 12-13.

9 In this case, I follow Pontani’s edition of scholia to books 1 and 2 ; see Pontani (2007). For scholia pertaining to other books of the Odyssey, I use a reprint of Dindorf’s edition (1855).

10 Eustath. Comm. ad Hom. Od. 1, 60, 11-16.

11 Eustath. Comm. ad Hom. Od. 1, 63, 15-16.

12 The line contains four dactyls, just as line 75, considerably shorter, and it has only one more letter than the previous line.

13 See S. West (1967) 17 ; Bolling (1945) 181-184.

14 P.Monts.Roca inv. 47 is catalogued and can be seen at <http://www.dvctvs.upf.edu/catalogo/ductus.php?operacion=introduce&ver=1&nume=354>.

15 Compare, in the aorist, Hesychius <ἦсεν>· εἴαсεν.

16 Eustath. Comm. ad Il. 2, 838, 13-16.

17 S. West (1967) 14. Note that none of the lines missing in our papyrus (697, 706 and 709) – and neither the final lines of the book, on which see below – are listed among those missing in the papyri studied by West.

18 For the scholia to the Iliad, I follow Erbse’s edition (1969-1988).

19 Eustath. Comm. ad Il. 2, 838, 16-19.

20 The paragraphos, maybe accompanied by a coronis, would be the sign expected in a papyrus from the third century BC ; see Schironi (2010) 76.

21 This is the case in P.Gen. inv. 90 (also III BC) ; see Schironi (2010) 88-89 and S. West (1967) 107-117, who nonetheless suggests there might have been some sign at the end of the line.

22 Roca-Puig (1998) 10. My reading of the line, as can be seen, differs slightly from Roca’s : I cannot see any traces of second omicron, nor can I see the final characters of the line.

23 What would be 708a, Roca edits θεω]ν̣ υπατοс κ̣α̣ι̣ [αριсτοс], supposing an invocation to Zeus which would therefore be included in the speech. However, under the microscope I rather see ] ִ ִ ִα̣θ̣α̣ν̣α̣τ̣οι̣.[]с̣ιν̣ [ ]ִ ִ ִ ; this might go together with the dative of the following line (πα]сιν), thus placing the end of Diomedes ‘ speech at line 708. The question will be dealt with in greater detail in the forthcoming edition of the papyrus.

24 See Jensen (1999) 22. She argues that the poet, in his dictation of the poems over a period of 24 days on the occasion of one of the Greater Panathenaea under the Pisistratid rule, would have rounded off his recitation at the end of the day, thus giving birth to the 24 books.

25 Thus S. West (1967) 20-24, who offers both negative and positive arguments to sustain the thesis that the book-division system familiar to us was already in use before the time of Zenodotus.

26 Book 10 following book 9 has aroused the critics’ suspicion, seeing that book 11 would naturally follow the last scene of book 9 ; see Hainsworth (1993) 150. But it is clear that our papyrus did have book 10 following book 9.

27 This seems to have been the view of the Ancients ; see recently Nünlist (2006), arguing for the reliability of ancient testimonies, which place the division of the epics into books at a stage later than their composition. This is also the view of many modern scholars, such as Ø. Andersen (1999) 39, or M.L./S. West (1999) 69, who think that book division goes back to the occasion of the Greater Panathenaea, thus agreeing on this point with Jensen, although in their opinion the division would have been made on a fixed, pre-existing text. Others, like De Jong (1999) 63, think that stops during the recitation would have taken place at « natural » places not necessarily fixed earlier, such as sunsets, sunrises, etc., and that « later, rhapsodes and book-sellers made use of the same devices to divide up the texts, each for his own purposes. Finally, the Alexandrian editors fixed this aspect of the Homeric text, just as they «settled» so many of its other variants (plus-verses, etc.). »

28 See however Heiden (1998), who defends an organic distribution of book ends in the case of the Iliad.

29 See Jensen (1999) 14-18 for different ways in which book-ends are « rounded off », one of them being precisely this one. In this respect, the suspected addition at the end of this book may have caused some puzzlement at the beginning of book 10 : far from enjoying a peaceful sleep, as is said in 9, 710-713, Agamemnon and Menelaus are restless and wake up the Greek generals. Of course it could always be thought that our scribe dropped the verses precisely for that reason, but this would equally be another indication that no such strong segmentation was felt at this point so as to indicate the widely acknowledged end of a book.