Ancient exegesis on Euripides for Commentaria et Lexica Graeca in Papyris Reperta

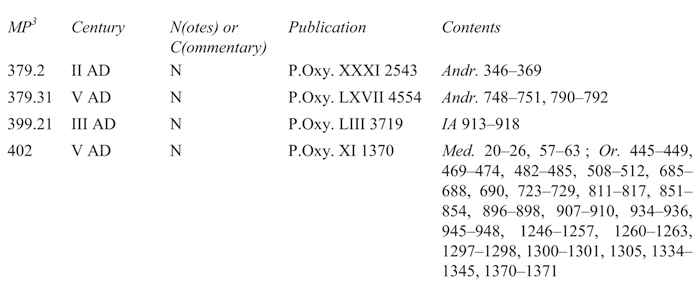

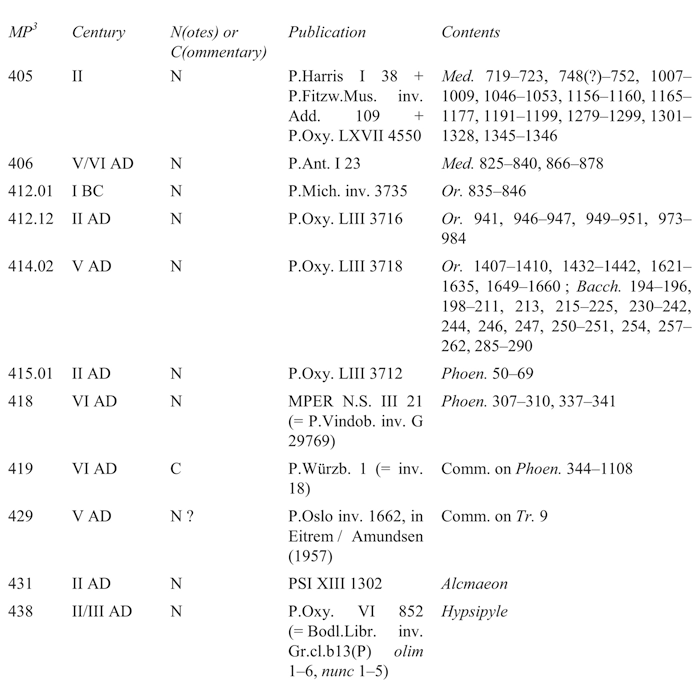

This is a preliminary report on some of the fifteen papyrus commentaries and annotated texts that will be included in a volume of Commentaria et Lexica Graeca in Papyris Reperta devoted to Euripides (see the accompanying table). All are on papyrus. Twelve are book rolls, two codices, and the nature of one text is debated. Only two are hypomnemata, both very late in date. Seven of thirteen annotated texts are from the high Roman period, five from late Antiquity, and one was copied in the late first century BC. Plays of the « Byzantine triad » are numerous : three texts contain Orestes, two Phoenissae, and one Hecuba. Five of the rest are from canonical plays ; the other two, both Roman in date, contain lost tragedies. In this paper I offer insights arising from examination of seven of the less-studied texts in the group. Although this fresh look at the texts yielded only a little new information, other facts have emerged from the research of others and from the practice of a little so-called « museum archaeology » which are worth recording. Furthermore, the seven texts presented here represent, reasonably well, the state of the rest of the material1.

In a few texts, new readings or possible new readings emerge, but their significance is generally slight. In MP3 415.01, for example, which is a crudely written second-century copy of Phoenissae, there are two interlineations above line 57 (κόραс τε δiссάс · τὴν μὲν Ἰсμήνην πατήρ | ὠνόμαсε). The first editor, Michael Haslam, read the note above διссάс as δύ]ο followed by a diagonal stroke. The second, above Ἰсμήνην, he transcribed as θ̣ ρ̣ and suggested θυγατερα had been written, with a diagonal stroke preceding it. I believe a form of this word was intended, but I am not sure so many letters can be crowded into the space available, despite the scribe’s small handwriting. In fact, the last trace visible appears to be suprascript, making θυγατε, i.e. θυγατε(ρα), an option. It would be a normal way to abbreviate the word, and the traces of the last preserved letter conform to the shape of the bottom left of the writer’s epsilons ; the top left portion, which the writer habitually begins a little to the right of the end of the crossbar, has broken off at the edge of the papyrus with the rest of the letter.

MP3 379.2, a second-century copy of Andromache 346-368, includes an unpublished scrap written in a smaller hand than that of the main text and surrounded by sufficient blank papyrus to show it comes from an intercolumn or margin. It is possible to read ἐ]κτελεῖ δ[, plausibly part of a gloss on 352 πορсύνειν or 365 ἐξετόξευсεν, or possibly part of a metaphrase of the gnomic observation in lines 368-369.

In the case of MP3 406, an Antinoopolis copy of Medea of the fifth/sixth century, four scraps with remnants of notes turn out not to have been published at all. Only letters, not words, are legible, but once they are available, we may hope that someone may find sense here.

MP3 402, a P.Oxy. « distributed » papyrus of the fifth century in Williams College Library, illustrates typical technical problems in the Euripides texts I examined. It contains copies of Medea and Orestes written in corrosive brown ink. In the editio princeps, Grenfell and Hunt printed ἄλ]λ̣ο̣ ἡ̣μ̣ι̣χ̣(όριον), a speaker note, beside Or. 1260. Where they saw ink, however – and the published plate confirms this – only a horizontal crevice remains, stained above and below where that ink has eaten through the fibers. It is impossible now even to verify the reading, which in any case inspired little confidence in the editors2. Like this papyrus, many of the texts I examined received the best possible consideration from the best papyrologists. As time has passed, however, ink has flecked off or eaten through papyrus, and edges have been lost, so that in some cases the best hope for extracting any more information is intuition and a good attitude.

Another papyrus, MP3 405, has yielded a few more secrets which although not exegetical at least untangle some of the modern history of the original book. A nicely written copy of Medea from the Roman era, it is divided now among three different British collections. The most substantial part is in Birmingham, among the Rendel Harris papyri now in the University Library. Another large fragment belongs to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. These two have been associated and dissociated over the years. The 2001 editors of three additional tiny scraps among the Oxyrhynchus papyri in Oxford identified them as part of the same manuscript as the Harris and Fitzwilliam pieces, apparently on palaeographical grounds. I have found evidence that secures the link and helps to explain how the three pieces reached their present locations3.

The Birmingham component was published first, in 1936, as P. Harris I 38. John E. Powell dated it to the second century. Two years later, in 1938, Denys L. Page published the Cambridge fragment in Classical Quarterly. Evidently Powell knew its existence before it appeared, for in the intervening year he is reported as saying it was part of the same manuscript as P. Harris I 384. Page was evidently unaware of this claim at the time of his own edition of the play the following year, and in any case he assigned his papyrus an earlier date. When the Oxford fragments finally appeared as P.Oxy. LXVII 4550 in 2001, the editors, D. Hughes and A. Nodar, accepted Powell’s assertion and dating. Thus the Cambridge and Birmingham fragments acquired a provenance.

Significantly, the inventory number of the Oxyrhynchus fragments indicates that they were found in the winter of 1903-1904, during Grenfell and Hunt’s third season at Behnesa5. The excavators will have sent them to Oxford with the rest of the winter’s finds at the end of that season. In fact, although they were last to be published, they were actually the first to reach England : the Birmingham and the Cambridge portions figure neither among the Oxyrhynchus « distributa » nor did they emerge in the Italian excavations of 1909-1914.

The first notices these two pieces receive are in 1922-1923, so many years after the excavators left Egypt that we are almost forced to conclude that they emerged from the ground separately. Pieces so large – large at least by comparison with the tiny pieces of MP3 405 that were actually recorded during the 1903-1904 season – would have come to the attention of Grenfell and Hunt if they had emerged while they were in Egypt, for substantial fragments of ancient literature were precisely what they were after6. It is theoretically possible that someone associated with the British – or the later Italian excavations in 1909-1914 – found these pieces, held them until 1922-1923, and then offered them for sale : texts did disappear from Egypt Exploration Society digs7. But this is not a likely explanation. The market value of papyri was already well known in 1903-1904. The excavation report for that year notes that « the dealers are at length turning their attention to Behnesa, and papyri continue to command extravagant prices in the market »8. Since papyri were good for ready cash even then, there was no particular advantage in holding on to them for nineteen or twenty years. All things considered, it seems most likely that the Birmingham and Cambridge texts turned up during the sebakh-mining of the early 1920s, probably not long before they entered the Harris and the Fitzwilliam collections in 1922-1923. But there are many other possibilities, and we shall probably never know the exact circumstances of the discovery of these two fragments. A little information about how they probably arrived in British hands has, however, come to light.

Powell’s preface to The Rendel Harris Papyri discreetly reveals only that the Birmingham portion of MP3 405 was acquired « privately in Egypt » in 1922-1923. Sixty years later he was more loquacious. To an interviewer for Times Higher Education, he described how in 1932 the Biblical scholar Harris, an old man by that time, related to Powell that « as curator of the Rylands Library in Manchester, he [Harris] (...) made his purchases surreptitiously and then used the hat boxes of his female companions to smuggle the papyri out of the country »9. Where Harris met the seller and whether he acted on his own or through an agent is not known. Circumstances suggest the transaction occurred at Oxyrhynchus, where many papyri traded hands that year. We know this from the reports of Petrie, who as Director of the British School of Archaeology in Egypt was conducting an archaeological (not papyrological) excavation of the ancient city that season. He records the vigorous activity of hundreds of sebakh diggers who during the war, with British and Italian excavators gone, started systematically mining the rubbish mounds where Grenfell and Hunt had made their finds. A new railway line built for the purpose facilitated their work. The sebakh-mining turned up papyri, « many » of which were « purchased from the diggers and dealers » that season10. We do not know whether Harris, in Egypt at the time, was on the site himself, but the circumstances at Oxyrhynchus were clearly ideal that winter for the Birmingham Medea fragments to have changed hands.

Furthermore, the accession record of the Fitzwilliam Museum fragment lists it as a 1922 gift of the British School of Archaeology in Egypt and thus leads right to Petrie himself11. Yet Petrie’s own report of donations made that year by the School contains, interestingly, only summary descriptions of sculptures and inscriptions and no reference to a Greek papyrus. This may be an oversight by the director of a specifically archaeological mission. But since we know – from the inventory number of the P.Oxy. fragments – that the Medea manuscript lay for centuries in a mound outside Oxyrhynchus, it is not likely that Petrie’s team came across it while excavating within the city. I suspect, rather, that sebakh diggers found the fragment and that a dealer brought it within Petrie’s orbit. The British School’s arrangement with the Egyptian government permitted export only of items excavated by his team. He may therefore just have quietly omitted reference to the papyrus in his report.

I suspect, in fact, that Arthur Hunt was an active participant in the disposition of both the Birmingham and the Cambridge fragments. The evidence, all circumstantial, is as follows. First, an established link already existed in 1922 between Hunt and the Fitzwilliam, for all the early Oxyrhynchus texts that Grenfell and Hunt distributed to Cambridge University have Fitzwilliam inventory numbers. Secondly, we know from Petrie that Hunt was at Oxyrhynchus, evidently to buy papyri, in 1922-1923 : « At Oxyrhynkhos many papyri were purchased from the diggers and dealers ; a few were retained for publication by Professor Hunt, the bulk were sent to Washington University, St. Louis, and others to Ann Arbor University, Michigan. »12 Third, Hunt made a transcription of the Fitzwilliam fragment, which Page consulted for his 1938 edition13. Finally, if the Harris and the Fitzwilliam pieces both changed hands at Oxyrhynchus in 1922, which seems likely, then Hunt, whose palaeographical acumen is legendary, may have seen them both, spotted the connection, and commented on it to Harris, who – as we saw – may also have been present14. This would explain Powell’s confident assertion, even before Page published the Fitzwilliam portion, that the two pieces came from a single manuscript.

Throughout the story, in any event, Hunt is a presence in the background, and I suspect was instrumental in the acquisition not only of the Fitzwilliam fragment but perhaps also, as agent or advisor to Harris, of the Birmingham piece. What dealers separate, however, we can virtually reunite, and some useful insights emerge from the exercise. The Birmingham pieces include the largest and most complete single fragment, which occupies most of a column and its surrounding margins. Because it includes the top and bottom lines of a single column of 34 lines, it demonstrates that the entire play occupied about forty columns, and that the three sets of fragments fall close together at the end of the play.

Two previously unnoticed facts reinforce the – presumably palaeographical – original identification of the Oxyrhynchus and Harris fragments. First, the final lines of two formerly adjacent columns, Medea 1312 (P. Harris) and 1346 (P.Oxy.), confirm the number of lines per column already known from the Harris text. Second, there is a previously unnoticed link between P. Harris fr. 1 and P.Oxy. fr. 1. The former contains the ends of Medea 719-723 and part of the adjacent right intercolumn, which extends upward for the space of several lines. High in this intercolumn are the barely legible remains of the names of Aegeus and Medea, written at the level that lines 748 and 749, spoken by those characters, must have occupied in the next column. Part of lines 748-749 survives, in fact, in a tiny Oxyrhynchus piece, but it comes from the middle of the column.

A technical point of interest in this manuscript, finally, is its lection marks, which are numerous in the lyrical portions of the Birmingham fragment. Several, added by a second hand, resemble a large, distinctly written apostrophe. In Roman texts, the apostrophe typically marks elisions, or separates pairs of vowels or consonants within a word. It does not separate words ; this is the job of the diastole. Nor does its function ordinarily vary within a text. In P. Harris I 38, however, both these conventions are undone, for the use of the apostrophe varies according to nature of the passage. In iambic trimeters, and six times in choral lyric, it marks elision, as usual. It is commonest in the choral song, however, where it marks word separations. Evidently in passages where the meter is complex, the diction elevated, and the scriptio continua more than usually difficult to parse, its role has been adapted and extended, perhaps to make recitation or memorization easier.

I end with two frequently discussed papyri, both very late commentaries with unsolved difficulties. P. Oslo inv. 1662 (MP3 429, fifth century) consists of nine lines of historical background explaining Euripides’ use of the epithet Παρνάсιοс in Trojan Women 9. Although no lemma survives, the mode of discourse is exegetic, and the learned comment corresponds closely to the scholia. A key question is the original form and the purpose of the text. Because the back is blank, the first editors assumed implausibly it was a remarkably late fragment of a papyrus roll, but this idea is now generally rejected15.

Marco Stroppa recently pointed out a serious objection to identifying it as a codex, however. The scribe’s writing, which runs across the fibers, also runs parallel to a kollesis16. In a typical book, whether roll or codex, one would expect script to run either along the fibers and across the kollesis (if the front of the papyrus is used), or across the fibers and the collesis both (if the writing is on the back). Here, it is at right angles to the direction expected. Two explanations come to mind : first, the text was part of a sheet from a squarish codex and it was written upon the wrong way by mistake. If so, it is part of a lefthand page, and its back is blank because the text on the previous page concluded higher up. Second, and more likely, the text was copied onto a loose sheet of papyrus.

Jean-Luc Fournet’s study of the physical characteristics of letters and documents of late Antiquity provides good reasons for preferring this option17. In the fifth century, as he shows, it became customary for letter-writers to write across the fibers, along the length of a sheet turned 90° from the orientation of a typical letter in earlier centuries. This may be in imitation, he suggests, of the practice of writing documents transversa charta, which was revived in the fifth century and became the rule by the sixth. I expect that P. Oslo was written by someone familiar with this practice, for whom it was natural to orient the papyrus as he would for a letter.

Another feature supporting the idea that the text was intentionally written transversa charta is the relative state of repair of the two sides. The side with writing is largely intact and in good repair ; the back, by contrast, is poorly constructed, with gaping spaces between strips of material18. Although its condition could be the result of later damage, it is also possible that this side, never intended to receive writing, was left somewhat unfinished in appearance.

As to why a writer would bother in the first place to copy learned material onto a loose piece of papyrus, we can only speculate. Its scholarly quality suggests it was to be put together with similar fragments to create a compiled commentary or, perhaps, scholia. As such, it will have served the same purpose as the thousands of « slips » from which James Murray compiled the Oxford English Dictionary19. But a simpler and less controversial explanation may be the likelier one, namely, that it is an odd note that a reader or teacher copied out and intended to slip inside his text of Trojan Women, or into a commentary on the play20. As such it will have served the same purpose as the 3x5-inch cards with useful notes and corrections that Herbert Youtie left behind in books in the papyrology collection in Ann Arbor21.

The last text is a leaf from a papyrus codex in Würzburg that contains a substantial part of a sixth-century commentary on Phoenissae (MP3 419). Written in variable, sometimes terrible, handwriting, it is in many parts scarcely legible. The codex is significant not only because it is one of the last examples of a scholarly tradition reaching back many centuries but also because its factual content, like that of the Oslo piece, is unexpectedly high in quality by comparison with most late exegesis. Other noteworthy features are its brevity (the single surviving page covers about 750 lines of the play and averages about one comment per thirty lines), the absence of any discussion of long stretches of text, and the disorder of some lemmata.

The text has occupied a succession of scholars from Wilcken, the first editor, to Maehler to Athanassiou to Stroppa, who has moved enquiry forward considerably22. He observes that such disorder is actually not unique : four of the ten surviving late hypomnemata in codex form show some such non-trivial disarray, and they tend, like the Wurzburg commentary, to be brief and selective. This is a small sample but it is a curious one. The reason for the disorderliness and the brevity of these four late works is unclear, and in truth there may be four or more different explanations. Collectively, however, the texts suggest something not considered before Stroppa’s suggestion : that there may have been readers in late Antiquity (and also earlier ?) for whom a set of succinct but not necessarily orderly comments on particular parts of a text – in lieu of the thorough and orderly marshalling of information typical of the most comprehensive ancient exegesis – was acceptable and useful23. If we avoid the easy assumption that P. Würzburg 1 and other disordered late commentaries are simply defective hypomnemata and entertain the idea, instead, that they may represent a different kind of reader’s aid, we may improve our understanding of the teaching and transmission of classical scholarship in late Antiquity. But four papyri is a weak foundation for any strong argument on the subject, of course.

This recent work on Euripidean exegesis has enabled me to corral details that went unrecorded at time of publication and to throw a little light on alterations needed in published texts, although many of the indicated changes involve only small alterations in the good work of our predecessors. The net effect of the research done so far, in fact, has been to confirm the impressively high quality of the work of the earliest editors of papyrus texts. It is a humbling experience.

Euripides Papyri Containing Commentary or Annotation

Bibliography

Athanassiou, N. (1999), Marginalia and Commentaries in the Papyri of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes (diss. London).

Avezzù, G./Scattolin, P. (ed.) (2006), I classici greci e i loro commentatori. Dai papiri ai marginalia rinascimentali (Rovereto).

Barber, E.A. (1937), « Bibliography of Graeco-Roman Egypt : Papyrology 1937 », JEA 24, 93-94.

Bowman, A.K./Coles, R.A. et al. (ed.) (2007), Oxyrhynchus : A City and its Texts (London).

Coles, R.A. (2007), « Oxyrhynchus : A City and its Texts », in Bowman/Coles (2007) 3-16.

Diggle, J. (1983), « On the Manuscripts and Text of Euripides, Medea », CQ 33, 339-357.

Donovan, B. (1969), Euripides Papyri I : Texts from Oxyrhynchus (New Haven).

Eitrem, S./Amundsen, L. (1957), « From a Commentary on the Troades of Euripides : P.Osl. inv. no. 1662 », in Arslan, E. (ed.), Studi in onore di Aristide Calderini e Roberto Paribeni II (Milano) 147-150.

Fournet, J.-L. (2009), « Esquisse d’une anatomie de la lettre antique tardive d’après les papyrus », in Delmaire, R./Desmulliez, J./Gatier P.-L. (éd.), Correspondances. Documents pour l’histoire de l’Antiquité tardive (Collection de la Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée 40, Série littéraire et philosophique 13, Paris) 23-66.

Grenfell, B.P./Hunt, A.S. (2007), « Excavations at Oxyrhynchus (1896-1907) », in Bowman/Coles (2007) 345-368.

Kelly, M. (1995), « A Professor of Greek «Just out of Nappies» », Times Higher Education (London, Sept. 1) <http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storyCode=95193§ioncode=26>.

Maehler, H. (1994), « Die Scholien der Papyri in ihrem Verhältnis zu den Scholiencorpora der Handschriften », in Montanari, F. (éd.), La philologie grecque à l’époque hellénistique et romaine (Entretiens sur l’Antiquité classique 40, Fondation Hardt, Genève/Vandœuvres) 95-141.

Maehler, H. (2000), « L’évolution matérielle de l’hypomnèma jusqu’à la basse époque. Le cas du P Oxy. 856 (Aristophane) et PWürzburg 1 (Euripide) », in Goulet-Cazé, M.O. (éd.), Le commentaire entre tradition et innovation. Actes du colloque international de l’Institut des traditions textuelles, 1999 (Paris) 29-36.

McNamee, K. (1998), « Another Chapter in the History of Scholia », CQ 48, 269-288.

McNamee, K. (2007), Annotation in Greek and Latin Texts from Egypt (Am. Stud. Pap. 45, Oakville, CT).

Montana, F. (2006), « L’anello mancante : l’esegesi ad Aristofane tra l’antichità e Bisanzio », in Avezzù/Scattolin (2006) 17-34.

Montanari, F. (2006), « Glossario, parafrasi, edizione commentata nei papiri », in Avezzù/Scattolin (2006) 9-15.

Montserrat, D. (2007), « News Reports : The Excavations and their Journalistic Coverage », in Bowman/Coles (2007) 31-39.

Murray, K.M.E. (1977), Caught in the Web of Words : James A.H. Murray and the Oxford English Dictionary (New Haven).

Pack, R.A. (1965), The Greek and Latin Literary Texts from Graeco-Roman Egypt (2nd ed., Ann Arbor).

Page, D.L. (1938a), Euripides Medea (repr. 1952-1967, Oxford).

Page, D.L. (1938b), « A New Papyrus Fragment of Euripides’ Medea », CQ 32, 45-46.

Perrone, S. (2009), « Lost in Tradition. Papyrus Commentaries on Comedies and Tragedies of Unknown Authorship », in Montanari, F./Perrone, S. (ed.), Fragments of the Past. Ancient Scholarship and Greek Papyri (Trends in Classics 1, Berlin) 203-240.

Petrie, W.M. Flinders et al. (1925), Tombs of the Courtiers and Oxyrhynkhos (British School of Archaeology in Egypt 37, London) <http://www.etana.org/sites/default/files/coretexts/15142.pdf>.

Stroppa, M. (2008), « Lista di codici tardoantichi contenenti hypomnemata », Aegyptus 88, 49-69.

Stroppa, M. (2009), « Some Remarks Regarding Commentaries on Codex from Late Antiquity », Trends in Classics 1, 298-327.

Turner, E.G. (2007), « The Graeco-Roman Branch of the Egypt Exploration Society », in Bowman/Coles (2007) 17-27.

Wilson, N.G (1967), « A Chapter in the History of Scholia », CQ 17, 244-256.

Zuntz, G. (1965), An Inquiry into the Transmission of the Plays of Euripides (Cambridge).

Zuntz, G. (1967), Die Aristophanes-Scholien der Papyri (2nd ed., Berlin).

____________

1 I am grateful for the gracious help I received from colleagues and custodians of papyri in each of the collections I visited : the Ashmolean Museum and the Beinecke, Bodleian, Columbia University, Oslo University, Sackler, University of Michigan, Williams College, and Würzburg University Libraries.

2 The crack is about 1,6 cm wide and 2 mm high, and deepest at the right-hand half of the note. One can perhaps make out a tiny dot of ink in the suprascript position where the lambda of ἄλ]λ̣ο should be, and possibly a low dot of ink like the tail of the descender of mu beneath the crack at about the midpoint.

3 There has been confusion about their location in modern times, and even the normally reliable catalogue of Roger Pack is inaccurate on this point : see Pack (1965) 40 no. 405. The Harris collection originally resided in the Selly Oaks Libraries of Woodbroke College. The Fitzwilliam fragment, as far as I can discover, went more or less directly to Cambridge after excavation. The two parts seem to have been separate since their discovery (or shortly thereafter).

4 See Page (1938b) ; Barber (1937). Although Page did not acknowledge Powell’s claim in Page (1938b), later printings of Page (1938a) have the note, « Mr J.E. Powell now states that Π7 and Π8 belong to the same Ms » (p. xlix). Those adopting Powell’s view (but unaware of the Oxford fragments) include Pack (1965) and Diggle (1983), but Diggle (1984) unites the three parts as Π5a, b, c and labels the Oxyrhynchus parts « ined. ». Donovan (1969), knowing nothing of the Oxyrhynchus fragments, excluded MP3 405 altogether.

5 The excavation records are reprinted in Grenfell/Hunt (2007) 355-357 (third season). For a table showing dates of the successive digs, see Montserrat (2007). On interpreting Oxyrhynchus inventory numbers, see PJ. Parsons’ note at the beginning of P.Oxy. XLII as well as Coles (2007) and Turner (2007). I am indebted to Dirk Obbink for a great deal of useful information and enlightening e-mail discussion of the vagaries of papyri from Oxyrhynchus.

6 See Grenfell/Hunt (2007).

7 In a letter to H.A. Gruber, Honorary Treasurer of the Egypt Exploration Fund, quoted at Turner (2007) 20, n. 2, Grenfell offers assurances about steps taken to reduce thefts. The chronology of Italian excavations at Oxyrhynchus can be found at <http://www.istitutovitelli.unifi.it/ricerca/scavi/campagne.html>.

8 See Grenfell/Hunt (2007) 355.

9 See Kelly (1995). Powell died in 1998.

10 « During all this digging, papyri are found, but apparently nothing else of importance », Petrie (1925) 1 and 12-13. A list of Petrie’s excavations, their sponsors, the distribution of the finds, and their publications is provided at <http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/petriedigsindex.html>.

11 Accession no. E.1.1922 (Antiquities) ; Reference Number : 52234 ; the online record is at <http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/opacdirect/52234/html>. Presumably it was in return for support from the University of Cambridge. See also Petrie (1925) pl. XXII and XXIII. According to Dr Lucilla Burn, Fitzwilliam Museum Curator of Antiquities, the British School of Archaeology in Egypt in the same year also donated three pieces of sculpture and inscriptions from various sites, and nothing more is known about the provenance of the papyrus (e-mail June 3, 2010).

12 See Petrie (1925) 1.

13 It survived in one of Hunt’s numerous notebooks, which focus primarily on Oxyrhynchus finds, according to D. Obbink. C.H. Roberts, who had done considerable conservation work in the Oxyrhynchus collection, brought the notebook to Hunt’s attention : see Page (1938b) 45-46, n. 1 and D. Obbink (e-mail June 3, 2010).

14 See Turner (2007) 23.

15 Editio princeps : see Eitrem/Amundsen (1957) 148. For a more recent opinion, Maehler (1994) 112-113.

16 See Stroppa (2008) 60-61 ; Stroppa (2009) 302-303.

17 See Fournet (2009).

18 I am grateful to Anastasia Maravela for reminding me of this fact.

19 Murray (2001).

20 For discussions of the origins of scholia, see Zuntz (1965) 275 n. ; Zuntz (1967) ; Wilson (1967) ; McNamee (1998) ; McNamee (2007) 83-85 ; Montana (2006) ; Montanari (2006).

21 I am grateful to Michael Haslam for extended e-mail conversation about this text.

22 See Maehler (1994) ; Maehler (2000) ; Athanassiou (1999) ; Stroppa (2009) 306-316.

23 Detailed coverage also survives, of course, late in Antiquity. The prime example is the extensive marginal notes of P.Oxy. XX 2258 (Callim., VI/VII AD) ; on the surviving commentaries on tragedy, see Perrone (2009) 236-240.