Antinoopolis and Hermopolis : a tale of two cities

δῶρον δ’ Ἁδρια[ν]ο̣ῖο πόλι[с], Νείλοι[ο] δὲ vῆ̣[сoс (P.Oxy. LXIII 4352, 14)

Hadrian founded Antinoopolis in Middle Egypt on the east Nile bank in an area once occupied by a small pharaonic settlement2. On the west bank across the Nile lay Hermopolis, which, when the new Hadrianic foundation appeared in 130, had existed for well over a millennium3. Hermopolis was a major city with a long history and rich tradition, which also, until then, had sole claim to the area, its fertile land and resources. The sudden appearance of the artificial Hadrianic construct is bound to have had a significant impact, economic and cultural, on Hermopolis.

This brief study is based mostly on papyrological evidence from or about Antinoopolis, and is part of a monograph on the history of Antinoopolis on which I am working at the moment. It aims to detect the levels of cross-fertilisation through the various stages of the symbiotic relationship, forced or organic, that developed between the two cities. It further seeks to touch upon the wider question of the geographical context in which the new foundation appeared. Archaeology only sheds light on the diachronic geographical context of Antinoopolis, namely the Pharaonic settlement detectable through a temple of Ramesses II. The more pertinent question of the status of the land that the new foundation was allocated and its surroundings so far remains unanswered ; since the papyrological evidence does not contain any explicit reference to it, it is rarely even asked. I hope to show that examination of the relationship between Antinoopolis and Hermopolis, apart from its intrinsic interest, may also hold the key to understanding the new foundation’s territorial status. It must be stressed from the outset that this study focuses on cities that had a specific territorial link to one another or one dictated by particular historical circumstances. It does not aim to engage in discussions concerning the theory of urbanism or of city networks.

Examining the sources relating to Hadrian’s new foundation, one can learn a lot concerning the population and laws of the new city and the privileges that Hadrian granted its citizens, either from direct references in imperial edicts or indirectly from other official documents4. What is strikingly absent from the sources is reference to the status of the territory that Antinoopolis was to occupy, in other words the land necessary to build the city itself and feed its population. In this respect, and given the proximity of Hermopolis, it is also interesting that there seems to be no evidence of any intended formal connection between the cities or any practical arrangement for their coexistence. Indeed the papyri corroborate this by further indicating very limited contact between the neighbouring cities for a while after the foundation of Antinoopolis.

The territorial question of course encroaches upon the greater issue concerning the status of the new foundation as a nomarchy, which seems to have confounded generations of modern scholars and ancient writers alike, probably because of confusion already evident in the papyri5. These are the aspects of the character and development of Antinoopolis on which I believe examination of its relationship with neighbouring Hermopolis may shed more light.

For the purpose of this examination, I have found it essential to add a third city to the equation, in order to act as a point of reference and allow comparisons. Since Hermopolis had a link to Antinoopolis that was geographical but not institutional, the city that lends itself most readily for comparison is Arsinoe, whose link to Antinoopolis was institutional but not geographical : Arsinoe was one of the main sources for the new foundation’s population, while the Fayum was about 170 km away as the crow flies6. Not unexpectedly, as we shall see, the pattern of contact between Antinoopolis and each of the two cities is very diverse.

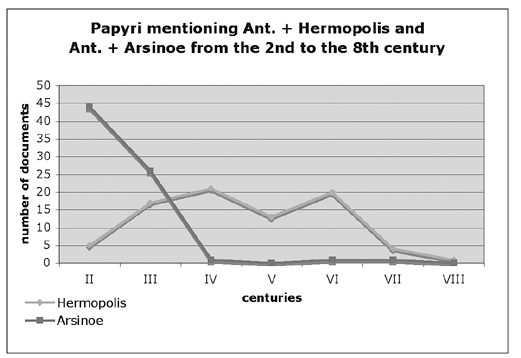

First a word on the sources : I use all the papyri which mention Antinoopolis and Hermopolis, as well as all those which mention Antinoopolis and Arsinoe. Those documents are not numerous, just under 160, which precludes any elaborate statistical exercises. They are however very well suited for the main task at hand, both in form and content, and well balanced in numbers, since both groups contain roughly the same number of documents. In these groups we find a mixture of petitions, contracts, letters and lists. Documents with references to personal names with the same roots as the cities (e.g. Philantinoos, Hermodoros etc.) have been excluded from these groups, with the exception of two or three cases where they seemed to have some significance.

One feature that immediately sets the two groups apart is the pattern of chronological distribution of the documents they comprise : the majority of the documents in the Antinoopolis/Arsinoe group are dated to the second century, that is in the 130s and soon after. There are also several documents in that group from the third century, but after that there are only some isolated occurrences, only one of which, in the sixth century, seems to have any significance at all. The pattern of the Antinoopolis/Hermopolis group is very different. Very few documents from the second century, more from the third, still more from the fourth and the same number in the sixth century, after a dip in the fifth ; then a sharp decline in the seventh and eighth centuries (see chart below).

This pattern eloquently reflects the nature and development of the relationship between each pair of cities. In terms of the connection between Antinoopolis and Arsinoe, the strong bond between the two cities was inherent in the very creation of the new foundation, since populating the new city involved nominating as Antinoite citizens great numbers of Arsinoites, some of whom also relocated to Antinoopolis. It is therefore to be expected that this process would leave a visible paper trail behind, as many of the new citizens found themselves with property and various responsibilities in both places7. The papyri are full of examples of the affairs of absentee landlords and of the complications caused by fragmentation of property and displaced residence in matters of tax, census, and inheritance8. Also attested are problems caused by the privileges granted by Hadrian to the Antinoites, which outside Antinoopolis were often a matter of contention9. As the years went by, those first Antinoites who identified themselves as ex-Arsinoite katoikoi or apoikoi eventually died out. Their families seem to have arranged their businesses in a way that did not require as much paperwork to travel between Antinoopolis and the Arsinoite nome. There is also evidence for the gradual abolition of Antinoite privileges, so the civic affiliation must have become unnecessary and eventually dropped out of the self-styling of Antinoites outside Antinoopolis.

A case in point is P.Hamb. I 15, where, out of four siblings, two appear as Antinoites and two not. Perhaps as the privileges become less important, the need or desire to be an Antinoite also diminishes and the title is just dropped. P.Hamb. I 15 is dated to 209, i.e. before the Constitutio Antoniniana, which might be expected to have been the cut-off point for the self-styling. No note in the thorough editio princeps explains this. Cadell (1965) reaches the conclusion that the gradual abolition of privileges may indeed have started earlier. Lewis, in reference specifically to the liturgy dispensation, sees in P.Mich. VI 426 the first signs of weakening of the privilege already in 199/20010 : ill health is offered as a more valid excuse to eschew the liturgy compared to the privilege to do so. He distinguishes between leitourgeiai and archai in an attempt to explain the inconsistencies in the application of the privileges in the first decade of the third century, contra Gapp (1933), who did not accept such a distinction and placed the abolition of the privileges in the mid-third century, on the basis mostly of P.Oxy. VIII 1119. However, Gordian confirmed at least the exemption from customs duties, and appeals because of transgressions against privileges are still attested in the later third century, though it is unknown whether they were successful11.

Coming back to the material involving Antinoopolis and Arsinoe, the numbers of documents that deal with both locations were gradually reduced to what would be expected between two metropoleis that lie quite far away from each other. According to Habermann’s calculations of the chronological pattern of papyrus documents in the main papyrus-yielding nomes, Arsinoite documentation peaks in the second century AD, drops to about half in the third and again in the fourth, and, after the fifth century dip, increases again in the sixth and seventh century12. In our evidence the second and third centuries follow that pattern, but then attestations of Antinoopolis and Arsinoe together virtually disappear. The differences are more significant in the Antinoopolis/Hermopolis group, where the pattern of our evidence goes up in the fourth century, not down as the Hermopolite documentation in general, and is also proportionately much higher in the sixth century.

As is clear from the graph, the chronological pattern of attestations in the Antinoopolis/Hermopolis group is the exact opposite from that of the Antinoopolis/Arsinoe group. It suggests very limited contact between the two cities at the beginning and more and more interaction as time went by. The dip in the fifth century may be symptomatic of the general dearth of papyrological material observable in fifth century Egypt. The dramatic decline of Greek papyrological evidence in the seventh and eighth centuries is due to the occupation of Egypt by the Arabs in 641. So, in view of the fact that the volume of documentation in the sixth century is at the same levels as that of the fourth century, it would be reasonable to assume that both the fifth century dip and the later decline reflect the overall pattern of papyrological evidence, not fluctuations specific to the contact between these two cities. In fact, as was indicated before, the pattern of contact between them becomes more and more pronounced as time goes by, as evidenced by this group’s documentation levels of the fourth century onwards, which are proportionally higher compared to the overall pattern of documentation from Hermopolis13.

The increasing interaction that is detectable in the papyri is primarily territorial. From the beginning of the third century, there is evidence of land and other real estate changing hands between Hermopolites and Antinoites on both sides of the Nile14. It is in these documents, relating to land, that the question of the exact nature of the territory belonging to Antinoopolis, as well as of its administrative status in relation to Hermopolis, becomes most relevant. In the introduction to P.Würzb. 8, Wilcken puts forth a convincing argument on how the nomarchy of Antinoopolis was founded on the east Nile bank on land that belonged to the Hermopolite nome. He uses Alabastrine as an example, which appears in the papyri interchangeably as Ἀλαβαсτρίνη τοῦ Ἑρμοπολίτου νομοῦ or τῆс νομαρχίαс Ἀντινόου before 296 and thereafter as του Ἀντινοΐτου νομοῦ15.

A similar case is that of Pesla, though the opinion has often been expressed that there is more than one location by that name, at least one belonging to the nome and one to the nomarchy16. Wilcken places Alabastrine firmly on the east bank for geophysical reasons as well, namely that that is where the alabaster quarries are to be found. He argues that this would make the Antinoite nomarchy subordinate to the Hermopolite authorities and part of the Hermopolite nome. Alternatively, the nomarchy may have been identical to a nome, in all but name, and would have belonged to the Heptanomia, the exact makeup of which has for a long time been quite elusive17. Be that as it may, it seems that whether or not the lands are ultimately considered Hermopolite, their immediate context is the Antinoite nomarchy. The elevation, or simply change, of the nomarchy to a nome during Diocletian’s reform must have clarified matters, while the controversy about its earlier status may just be the result of geographical and administrative inexactitude on the part of the ancient sources.

One should also take into account horizontal Nile migration, which would have played an important role in shaping the area of cultivable land available to the inhabitants of Hermopolis in the course of its long history. The foundation myths and ensuing tradition about Hermopolis say that it was built on an island, and it may well have been18. Even the 700-odd years of the history of Antinoopolis covered by papyrological sources constitute a sufficiently lengthy time-span for visible migration to have occurred. The Antinoite bank remained unaltered probably because of human intervention, according to Bunbury (forthcoming), while there is no evidence that the Hermopolitan side did not move ; in fact, if it did, that might go quite some way towards explaining some of the information found in the papyri regarding lands of uncertain status and Hermopolite shipping.

So after Diocletian’s reform the two administrative areas obtained the same status, whatever their hierarchy may have been before. But this did not result in two separate and self-contained areas of habitation and cultivation around each urban centre. A relevant body of evidence is the fourth century P.Herm.Landl.19 In its list of land and payments there is a section headed Ἀντινοϊτικὰ ὀνόματα. The meaning of these is not obvious and has left room for different interpretations : does it refer to Antinoites owning land in the Hermopolite nome, or in the Antinoite nome itself ? The editors provide a discussion of this in their introduction, where they convincingly side with the former interpretation, accepted by most scholars, that the land in question is situated in the Hermopolite20. If this is so, in these papyri we have ample evidence that by the fourth century there was extensive land ownership by Antinoites in the Hermopolite nome.

Apart from P.Herm.Landl., thoughout the papyri, there are also many isolated examples of Antinoites owning or leasing Hermopolite land, from the third century on. We only learn of some by chance, such as in the case of land sale contracts between Hermopolites, where, in enumerating the neighbours of the plot, one or more happen to be Antinoites21. In sale and lease contracts we also find Hermopolite land changing hands between Antinoites, and Hermopolite land being leased to Hermopolites by Antinoite owners22. When it comes to the reverse, the bulk of examples of landholding in the Antinoite nome by Hermopolites lies later, mostly in the sixth century23. In the same documents, but also in others not relating to landholding and farming, we find citizens of Antinoopolis residing permanently or temporarily in Hermopolis and vice versa24. The participles καταμένων, παρών, διάγων, ἐφεcτώc are the expressions normally used to denote this displacement, while in the seventh century Hermopolite tax-lists (P.Sorb. II 69) several persons are described as (ἀπὸ) Ἀντινόου.

By the third century AD, we also find the first families formed by marriage between Antinoites and Hermopolites25. In the earliest of these documents, when the privileges of the Antinoites are still important, the children of an Antinoite father and a Hermopolite mother are explicitly described as Antinoites26. Of course, by inference, these are also examples of displaced residence, as at least one of the spouses would have had to relocate.

The evidence about trade between the two nomes is quite limited, but there are a few examples in the sixth and seventh centuries, mostly for imports from Hermopolis, but also for export of barley from Antinoopolis to Hermopolis27. Much better attested are cases of commercial undertakings, mostly shipping, involving both Antinoites and Hermopolites28. Already in the early third century there are examples of Antinoite and Hermopolite shippers carrying out joint ventures to transport grain down the Nile. Later on we find examples of skippers from either nome arranging with the authorities of the neighbouring nome to transport their grain.

Examples of real interaction between the officials of the Hermopolite nome and the Antinoite nomarchy first occur in the third century, though the bulk of them occur post-296, when the administrative position of the new nome gains in importance29. It is in a document from the year 300 (P.Panop.Beatty 2) that we find the first clear reference to the Antinoite nome, listed among the other nomes in the jurisdiction of the epitropos of the Lower Thebaid. The new administrative make-up of the Thebaid required more collaboration among the high officials, and this is recorded in the papyrological documentation, since officials and councillors from both nomes frequently featured together in the fourth century in documents referring to the affairs of the eparchia.

As was noted before, in the second century there are very few documents that indicate any connection between the two cities, and all of them are mostly incidental attestations of the cities in the same document30. Having investigated the issues of landownership and residence, trade and administration, which are most significant in establishing the nature of the connection between Antinoopolis and Hermopolis, we can see that it is in the third century that we find the first evidence of real contact between the two cities, which gradually increases as the two neighbouring metropoleis evolve together and as their position becomes clearer with Diocletian’s reform. Disputes, mostly over the ramifications of Antinoite privileges, indicate that the acceptance of the new foundation and of its citizens may not have been straightforward.

If Wilcken is right about the land surrounding Antinoopolis on the east bank initially belonging to the Hermopolite nome, it could be that it was gradually bought up by Antinoites, so that when it came to Diocletian’s reform it became de facto part of the new Antinoite nome – which would certainly not have pleased the Hermopolites. One has to wonder if the self-styling of Hermopolis as « most ancient », attested from the end of the second/beginning of the third century onwards, might not be partly due to resentment against the new neighbours31.

Be that as it may, I hope to have shown that, while Arsinoe played an important part in shaping the nature and character of the new Hadrianic foundation, it was Hermopolis that developed the more significant long-term interconnection with Antinoopolis. In the earlier period, the emphasis of the foundation was on Hellenic culture, embodied by the Arsinoites who came from a more Hellenised area, the Fayum. Hermopolis always had a very strong indigenous Egyptian identity. As the Hellenic element faded into the background after the third century, the link to Hermopolis became much stronger and more evident. Throughout this process, the territorial and administrative link that developed between the cities, whether it constituted a harmonious or antagonistic co-existence, is a significant aspect of the identity of Antinoopolis, and so continued into Late Antiquity.

Bibliography

Bagnall, R.S./Rathbone, D.W. (2004), Egypt from Alexander to the Copts. An Archaeological and Historical Guide (London).

Boak, A.E.R. (1932), « A Petition for Relief from a Guardianship. P.Mich. inv. no. 2922 », JEA 18, 69-76.

Bowman, A.K. (1985), « Landholding in the Hermopolite Nome in the Fourth Century A.D. », JRS 75, 137-163.

Braunert, H. (1964), Die Binnenwanderung (Bonn).

Bunbury, J. (forthcoming), « The Development of the Capital Zone within the Nile Floodplain », in Proceedings of the Conference « The Graeco-Roman Space of the City in Egypt : image and reality », Tarragona 2010.

Cadell, H. (1965), « P.Caire IFAO Inv. 45, P.Oxy. XIV 1719 et les privilèges des Antinoïtes », CE 40, 357-363.

Calament, F. (2005), La Révélation d’Antinoé par Albert Gayet (Le Caire).

Drew-Bear, M. (1979), Le nome hermopolite. Toponymes et sites (Ann Arbor).

Drew-Bear, M. (1997), « Map 77 : Hermopolis Magna » <http://mail.nysoclib.org/Barrington_Atlas/BATL077.PDF>, last accessed 8 Dec. 2010.

Fowden, G. (1993), The Egyptian Hermes. A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind (2nd ed., Princeton).

Gapp, K.S. (1933), « A Lease of a Pigeon-House with Brood », TAPhA 64, 89-97.

Gigli Piccardi, D. (2002), « Antinoo, Antinoupolis e Diocleziano », ZPE 139, 55-60.

Habermann, W. (1998), « Zur chronologischen Verteilung der papyrologischen Zeugnisse » ZPE 122, 144-160.

Hoogendijk, F.J.A./Van Minnen, P. (1987), « Drei Kaiserbriefe Gordians III. an die Bürger von Antinoopolis », Tyche 2, 41-74.

Jördens, A. (2009), Statthalterliche Verwaltung in der römischen Kaiserzeit : Studien zum praefectus Aegypti (Stuttgart).

Jones, A.H.M. (1971), Cities of the Eastern Roman Provinces (2nd ed., Oxford).

Kühn, E. (1913), Antinoopolis : ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Hellenismus im römischen Ägypten (Göttingen).

Lewis, N. (1982), « A Restudy of SB VIII 9897 », APF 28, 31-38.

Lewis, N. (1997), The Compulsory Public Services of Roman Egypt (2nd ed, Firenze).

Pintaudi, R. (2008), Antinoupolis I (Firenze).

Roeder, G. (1959), Hermopolis 1929-1939 (Hildesheim).

Shaw, I./Nicholson, P. (1995), British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London).

Smolders, R. (2005), « Philosarapis » <http://www.trismegistos.org/arch/archives/pdf/192.pdf>.

Taubenschlag, R. (1959), « Die kaiserlichen Privilegien im Rechte der Papyri », in Opera Minora II (Warsaw), 45-68.

Thomas, J.D. (1970), « The Administrative Divisions of Egypt », in Proceedings of the 12th International Congress of Papyrology (Toronto).

Thomas, J.D. (1974), « A New List of Nomes from Oxyrhynchus », in Akten des XIII. internationalen Papyrologenkongresses (München).

Wilcken, U. (1935), « Referate : IX. J. Eg. Arch. 18, 69 ff. », APF 11, 132-133.

Zahrnt, M. (1988), « Antinoopolis in Ägypten. Die hadrianische Gründung und ihre Privilegien in der neueren Forschung », ANRW II 10.1, 669-706.

____________

1 This paper was written during the year 2010, when I held a scholarship from the Botsaris foundation at the Institute of Greek and Roman Antiquity, National Hellenic Research Foundation. I wish to thank both for their support. I am grateful to Alan Bowman and Garth Fowden for critical reading.

2 See Calament (2005) 51-53 ; also Pintaudi (2008).

3 See Bagnall/Rathbone (2004) 162-164 ; Shaw/Nicholson (1995) 73-74. The antiquity of Hermopolis is evident on the basis not only of its archaeological remains – see e.g. Roeder (1959) – but also of its foundation myths, which identify it as the first city after the creation of the world ; see Fowden (1993) 174-175.

4 On the privileges, see Kühn (1913) 153-161 ; Taubenschlag (1959) 45-68 ; Hoogendijk/Van Minnen (1987) 71-74 ; Zahrnt (1988) 690-700 ; P.Diog., p. 25-29 ; Jördens (2009) 334-338.

5 See Thomas (1970) for examples of incorrect notions of the administrative setup of Egypt in the sources.

6 The tone of P.Gron. 18, 10-11 (III/IV AD), ἄχρι τοῦ Ἀρcινοείτου ἐφθ[ακέν]αι, after mentioning Antinoopolis, implies that it was seen as quite far away.

7 See Braunert (1964) 123-124.

8 Absentee landlords : BGU I 300, P.Kron. 42, P.Mil.Vogl. III 180 and 181, P.Oxf. 11, SB XXII 15781, P.Fam.Tebt. 37, SB VIII 9906, PSI XV 1531, P.Mich. VI 422, 423 and 424 (all three on the same topic), P.Fam.Tebt. 51, P.Fam.Tebt. 52 ; also possibly P.Mich.Mchl. 7 and SB VI 9616 though their content is difficult to reconstruct. Census : SB XXIV 16013, P.Fam.Tebt. 44, P.Mich VI 370, P.Fam.Tebt. 48. Real estate : P.Mich. VI 364, P.Stras. IX 894, P.Mich. XII 627. P.Mil. II 54 would belong to this group, but inspection of the plate suggests the purported reading Ἀντινοοπ(ολί)τ(η) (a hapax) to be erroneous. The text looks like ἀντικ(νημίῳ) ἀριcτ(ερῷ), though οὐλή is missing. Taxation : SB XVI 12678, P.Fam.Tebt. 42, W.Chr. 29, BGU VII 1588. Registration of the first Antinoite minors : P.Fam.Tebt. 30. Inheritance : P.Diog. 17, M.Chr. 310, BGU I 168, P.Fam.Tebt. 43, P.Diog. 11 and 12, BGU VII 1588, P.Tebt. II 319, P.Tebt. II 326.

9 P.Iand. VII 140, SB XVI 12290 (see Lewis [1982]), P.Würzb. 9, SB V 7558. For SB XVI 12678, P.Fam.Tebt. 42, see also above, section on taxation ; P.Mich. VI 425 and 426.

10 See Lewis (1997) 140-142.

11 See Hoogendijk/Van Minnen (1987) 71-74.

12 See Habermann (1998) 148.

13 See Habermann (1998) 150.

14 P.Flor, III 383, P.Lond. III 954 (=M.Chr. 351), SPP V 119, P.Herm.Landl. 2, PSI XIII 1341, SB XXII 15618, SPP XX 121, SB XVI 12948, P. Köln III 153, P.Berl.Zill. 6, P.Stras. V 338, P.Hamb. I 23, P.Stras. VIII 751, SB XVIII 13170, P.Ross.Georg. III 49.

15 P.Lond. III 1157, P.Stras. I 5, SB XVI 13030, SB XXII 15311, SB XII 15618, SB XXII 15620. Drew-Bear (1979) does not clarify this. See also Jones (1971) 311.

16 See Drew-Bear (1979) 204-206. She cites Wilcken in P.Würzb. 8, who suggests that there are in fact three different villages by that name, and Kühn (1913), who only distinguishes between Pesla Ano and Pesla Kato. She explains the discrepancy of belonging to the Hermopolite nome or the Antinoite nomarchy as referring to Kato and Ano respectively. The only certain geographical reference is in the Itinerarium Antoninianum, which mentions a village called Pesla on the right bank, about 35 km south of Antinoopolis. Drew-Bear (1997) identified Pesla Ano with the Pesla in the Itin. Anton. and placed Pesla Kato north of Hermopolis Magna.

17 Thomas (1970) 467-468 argues for a Heptanomia which eventually, in the third century, encompassed eleven nomes, a suggestion that was subsequently confirmed by P.Oxy. XLVII 3362, published a few years later, about which see Thomas (1974). Even with the knowledge gained from this document, though, the question regarding the status of the Antinoite nomarchy is not yet settled.

18 See P.Oxy. LXIII 4352 ; also Gigli Piccardi (2002) 57.

19 Various attempts at a more precise dating have been made. The HGV dates P.Herm.Landl. 2 to after 346/347, while the editors of the texts devote an extensive part of the introduction to this question ; see P.Herm.Landl., p. 14-20 ; also Bowman (1985) 143-144.

20 See P.Herm.Landlisten, p. 24-26.

21 SPP V 119, iv, SB XXII 15618, SPP XX 121, P.Ross.Georg. III 49.

22 Hermopolite land changing hands between Antinoites : PSI XIII 1341, SB XXII 15618. Hermopolite land being leased to Hermopolites by Antinoite owners : SB XVI 12948.

23 P.Köln III 153, P.Berl.Zill. 6, P.Hamb. I 23.

24 P.Ryl. II 170, PSI IX 1067, P.Ant. III 192, P.Herm.Landl., SB VIII 9763, P.Köln III 153, P.Stras. V 317, SB V 8029, P.Cair.Masp. II 67165, P.Cair.Masp. II 67155, P.Hamb. I 23, P.Sorb. II 69, SB XVIII 13170.

25 PSI XII 1258, PSI IX 1067, P.Lond. III 1164F ; P.Cair.Masp. II 67155.

26 On the privilege of ἐπιγαμία, see Zahrnt (1988) 690-693 ; P.Diog., p. 26.

27 P.Prag. I 45 and 46, SB XX 14702.

28 P.Hib. II 216, SB XIV 11551, CPR V 10, SPP II p. 34, P.Grenf. II 80, 81 and 81a, P.Stras. VII 654. Also in the aforementioned P.Ant. III 192, relocating to the Hermopolite nome for three months on business may well imply that the sender was involved in a business venture together with Hermopolites. P.Oxy. XLIII 3111, a freight contract of 257, was signed in Antinoopolis and involves the transport of wine up the Nile from Oxyrhynchus to Hermopolis, but all the parties involved are Oxyrhynchites. The editors suggest as a likely explanation of why the contract was signed in Antinoopolis that perhaps the parties had just made a delivery there and were now arranging their next venture.

29 P.Oxy. XXXI 2560, P.Panop.Beatty 2, SB VI 9558, P.Stras. IV 296, SB XVIII 13769, P.Flor. I 95, SB X 10568, SB V 7758.

30 P.Oxy. XLVII 3362 is a list of nomes of the second half of the second century ; P.Iand. VII 140, of 151, is an edict regarding Antinoopolis sent to all the strategoi of the Heptanomia, where also the name of the Hermopolite nome occurs. P.Ryl. II 78, of 157, is an official letter from the prefect to various strategoi, including the Hermopolite ; it features an infuriating lacuna before Ἀντινόου which obscures the office of the person in charge, presumably the nomarch. SB V 7558, of 173, is a famous case of wrongful assignment of a guardianship for an orphan to an Antinoite. The deceased was a Roman living in the Hermopolite nome, so the Hermopolite exegetes is asked to find another guardian. The document is also published as FIRA III 30. For the editio princeps, see Boak (1932) and for further comments Wilcken (1935).

31 Ἑρμουπόλεωс τῆс μεγάληс ἀρχαίαс καὶ λαμπρᾶс καὶ сεμνοτάτηс. The only other city to style itself ἀρχαία is Heracleopolis (ἀρχαία καὶ θεοφιλήс or θεόφιλοс, but only in a handful of instances, mostly in the third century).