P.Köln XII 468 and reading homerin late roman/early byzantine panopolis

P.Köln XII 468, published in 2010, is made up of some fifty fragments from two collections that of the University of Cologne and that of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina2. The Cologne fragments had previously been edited by Bärbel Kramer as P.Köln I 40 in 1976, but the greater number, later discovered at Duke, were unpublished and could in many cases be joined to the Cologne pieces directly3. As it turned out, these extended thirty-three of the ninety verses partly preserved by the Cologne fragments and contributed remains of a hundred and ninety new verses, thereby substantially increasing the amount of surviving text. They also provided parts of five columns previously unrepresented (col. IV, V, XII, XV and XVI) and made it possible to determine the content of four of these (col. IV, V, XII, XV) and two others (col. X and XIV) more precisely.

In what follows, I intend to illustrate some of the noteworthy features of P.Köln XII 468 briefly, in the hope of calling attention to the importance of the papyrus and encouraging those who might be interested to peruse the original edition4.

The fifty or so fragments, ranging from the medium-sized to the minute, come from a papyrus roll whose recto originally contained at least the third and fourth books of the Odyssey and whose verso was never reused5. That the roll did in fact host at least these two books was already fairly clear from fr. f and put beyond all doubt by fr. 166. The former preserves the ends of Od. 3, 489-496 (493 is missing) in its first column and faint traces of the initial letters of Od. 4, 18-21 in its second the latter parts of the last three verses of the third book (495-497) and of the first four verses of the fourth, separated by a blank space of around four lines, in its first column, and the first letters of Od. 4, 25-27 in its second. No trace of an end-title or a paragraphos or a coronis survives7. Whether the roll contained further books of the poem is unclear, but the fact that it certainly contained at least two is of some interest8.

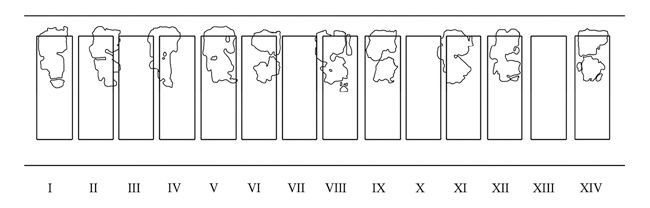

Thanks to a number of fragments partly preserving the upper margin or the remains of two columns or both, it was possible to reconstruct sixteen consecutive columns of the roll and to determine that these contained an average of twenty-nine lines of text9. Given an estimated column-to-column width of around 7 cm, then, the original roll must have been at least 3,25 m long10. That in its earlier state it was a minimum of 20 cm in height could also be calculated on the basis of the largest of the surviving fragments11.

Unlike the majority of surviving Homeric papyri, written in various styles of more or less formal bookhands, the text of this Odyssey papyrus is penned in a smallish, upright, elegant, cursive script, which might be described as a business hand influenced by the chancery style12. Though the use of a non-literary script for a work of literature is of course well attested, this particular combination is still worthy of note13. The influence of the chancery style can be seen above all in the artificial lengthening of the strokes of certain letters. As is often the case with chancery scripts, the initial letters of the lines are enlarged and the final letters whose ductus allows it (alpha, epsilon and sigma) drawn out horizontally into the space between the columns. Fr. 17, which preserves line-ends on the left and line-beginnings on the right, offers a good example of both phenomena14. In the left-hand column, the upper stroke of sigma at the end of Od. 4, 18, 19, 21 and 22, the right-hand diagonal of alpha at the end of Od. 4, 25 and the middle stroke of epsilon at the end of Od. 4, 26 are all prolonged. In the right-hand column, the letters at the beginning of the lines are written noticeably larger and stand out on account of their size.

The first editor of the Cologne fragments rightly drew attention to the remarkable similarity between the handwriting of this manuscript and the script of the famous Bodmer rolls of books five and six of the Iliad (published as P.Bodm. I 1 and 2)15. These are written on the verso of sections of the same land register concerning the Panopolite nome and can be dated approximately, thanks to the terminus post provided by it 213/214, the latest date deducible from a 22nd regnal year and mention of Aurelii, or AD 215/216, if there is an allusion to Caracalla’s planned visit to upper Egypt16.

A further clue to this dating comes from the hand that added Od. 4, 344 in the upper margin of col. XIV17. The verse had been mistakenly omitted by the scribe along with verses 343 and 345. Although very little of this hand is preserved, it closely resembles a cursive of the third century AD. The use of the apostrophe in this marginal addition to separate double consonants, which began to take hold in the third century, too, points in the same direction18.

A striking feature of this Odyssey roll, which has hitherto gone unnoticed, is the occasional presence of short blanks within the text. The enlargement of the letters following them is a corollary. Since these blanks, when they occur, normally fall at the caesurae, it appears that they were meant to articulate the verses metrically. In Od. 3, 460, for example, a blank is left after αὑτὸν at the third-trochee caesura, in 464 after λοῦcεν at the hephthemimeral caesura and in 465 after ὁπλοτάτη at the penthemimeral caesura19. In each of these instances, the following letter is also clearly enlarged the pi of πεμπώβολα in Od. 3, 460 (ἔχον was mistakenly omitted), the kappa of καλὴ in 464 and the theta of θυγάτηρ in 465. In light of such certain occurrences, cases of uncertain blanks coinciding with a caesura (or other metrical division) can perhaps be given the benefit of the doubt, especially when the next letter looks larger than normal.

To my knowledge, the marking of the caesurae of hexameters is attested in only one other papyrus and is therefore of especial interest. In the much earlier P.Köln VIII 328, assigned by its editor to the period straddling the first centuries BC and AD and referred by him on account of its outward appearance to the sphere of the school, the caesurae are regularly indicated by means of dicola and blanks the penthemimeral caesurae in verses 3, 4 and 5; the third-trochee caesura in verses 6 and 7 and probably the bucolic diaereses in verses 2 and 7. In verses 2 and 6, on the other hand, the same means apparently serve to indicate syllable division in ἐc:ήλυθον and Πά:ριν respectively.

A recently published teacher’s dipinto from Trimithis in the Dakhleh Oasis, however, is also perhaps of relevance in this connection20. The text is written on the wall of a schoolroom and consists of a series of epigrams, which may have served pupils as models for composition21. Whatever their purpose was, the middle or high point occurs several times at the third-trochee caesurae of the hexameters in I 9 after Xαpίτεccι, in I 13 after θαρcεῖτε and in II 4 after χαρίεντεc22. In I 5, on the other hand, there is no mark at the caesura after νεύcειεν.

But, since our papyrus is clearly not a school exercise, the occasional metrical articulation of the text likely reflects a learned concern with the structure of the Homeric hexameter at a time when this verse measure had undergone and was undergoing profound modification23. In any case, it implies a relatively high cultural level on the part of the person who introduced it.

It is a widely held belief that Homeric papyri of the Roman and Byzantine periods have little or nothing to contribute in textual matters24. I do not wish to dispute this view here, but merely to point out that it is not quite true of the present papyrus manuscript. Of course a number of the variations are mere slips of the copyist. On three occasions, for example, he was induced by a homoeoarcton to omit verses25. Within verses too, at the level of letters and words, he committed various mistakes. One passage (Od. 4, 339-54 preserved in Fr. mn+26+27) can be singled out as noteworthy, though fortunately not entirely representative, on account of the frequency and variety of scribal error. Within a few lines the copyist omitted letters in Od. 4, 339 and 349, added a superfluous letter in 340 and word in 351, confused letters in 342 and, to top it all off, left out verses 343-34526. All this is more or less run of the mill, but significant for an overall assessment of the papyrus.

Alongside these blunders, however, occur a number of divergences from the rest of the tradition, or a part of it, that can be taken seriously. Of the several new variants only one can be dealt with here in any detail27. The long drawn-out middle stroke of epsilon in line 2 of Fr. 1, which contained Od. 3, 44, shows that it must have been the last letter of the line28. In this text, then, the participle stood in the dual (μολόντε) and not in the plural (μολόντεс) as in the rest of the tradition. Morever, the new reading seems to be no mere slip of the copyist. For, although Telemachos and Athena-Mentor have sailed to Pylos in the company of others, it is only the two of them who disembark and betake themselves to Nestor, Nestor’s sons and the other Pylians, as is also plain from ἀμφοτέρων at the beginning of verse 37 (ἀμφοτέρων ἕλε χεῖρα καὶ ἵδρυcεν παρὰ δαιτὶ). In all likelihood, the dual here is a learned conjecture and the fruit of a careful examination of the context29. On a close reading of the passage, the copyistor somebody before himnoticed that the participle in reality referred to only two people and, as the metre allowed it, replaced the plural with the dual form30.

As for the many known variants, the papyrus shows that they go back at least to the late Roman period, thus generally providing the earliest direct support for them. This is of particular interest in those cases in which the variants are only rarely attested or, though more or less well attested, have been rejected by some or all of the editors in favour of another reading31.

All in all, the papyrus shows over a comparatively lengthy stretch of text to just what degree an individual copy of Homer could, even in the late Roman or early Byzantine period, take on its own particular form and vary from the traditional text familiar to us from our editions32.

But where was this copy made and by whom To the close similarity between the handwritings of P.Köln XII 468 and P.Bodm. I, the first editor of the Cologne fragments added the fact that, of lectional signs, only the apostrophe and trema are employed in these rolls33. Telling, I think, too is the very use of such a script to copy whole books of Homer. Clearly only a detailed comparison of all features of the papyri could provide sufficient data for a serious treatment of this issue, but even the points of contact between P.Köln XII 468 and P.Bodm. I just referred to point to a possible common origin of the rolls.

In addition to P.Bodm. I, there is, however, a further indirect link between P.Köln XII 468 and the Bodmer papyri, which incidentally bolsters the possibility of a relation between the Cologne Odyssey and the Bodmer Iliad rolls. P.Köln XII 468 is one of seven papyri divided between Cologne and Duke of which the Duke parts all derive from the collection of the archaeologist David Moore Robinson34. Of these, two also come from the same papyri as fragments preserved in the Geneva Library (P.Gen. inv. 271 and P.Gen. inv. 272), and one belongs to the same Menander codex as pieces in possession of the Fondation Bodmer.

Now, assuming a common origin, the Bodmer papyri might provide two clues as to the provenance of the Cologne Odyssey roll. The first is that the Bodmer Iliad books are written on the back of two sections of the same land register from the Panopolite Nome35. The second, not incompatible with the first, is that the bulk of the Bodmer papyri may derive from a single discovery consisting of the buried library of some institution, though the constituent texts, the kind of institution involved and the exact site of the find are all a matter of scholarly debate36.

As to the writer of our roll, he was probably an educated clerk from Panopolis or its environs, who earned his living by copying official documents during the day and used the same hand he employed at work to transcribe literature for himself and others in the evenings and at the weekends37. Hence, on the one hand, the interesting readings and metrical articulation and, on the other, the haste-and fatigue-induced errors. He may even have belonged to a group of more or less learned enthusiasts who in their leisure time prepared editions of Greek literature in a kind of circolo di scrittura38.

Panopolis certainly satisfies the conditions for such an assumption. As district capital, it was not only an administrative but of necessity also a cultural centre39. The evidence, both papyrological and other, clearly supports this picture. The papers of Aurelius Ammon and his family (P.Ammon I and II) as well as the texts belonging to the Bodmer Library (P.Bodm.) document an interest in Greek literature among inhabitants of the town and the surrounding area, at least in the higher social strata, and the Strasbourg fragments of Empedocles (P.Strasb. gr. Inv. 1665-1666), likely discovered there, suggest that it was of long standing40. Panopolis too, as is well known, produced such poets as Cyrus, Nonnus and Pamprepius, whose hexameter poems imply a thorough acquaintance with Homer and the entire epic tradition41. Without teachers, some of whose names are actually known, educational institutions, books, libraries, both public and private, copyists and scriptoria, all this would hardly have been possible42. It is in such a context that we can easily situate our Cologne-Duke Odyssey (and Bodmer Iliad) rolls.

Bibliography

Agosti, G. (2001), « Considerazioni preliminari sui generi letterari dei poemi del Codice Bodmer », Aegyptus 81, 185-217.

Agosti, G (2002), « I poemetti del Codice Bodmer e il loro ruolo nella storia della poesia tardoantica », in Hurst, A./Rudhardt, J. (éd.), Le Codex des Visions (Recherches et Rencontres. Publications de la Faculté des Lettres de Genève 18, Genève) 73-114.

Agosti, G. (2010), « Eisthesis, divisione dei versi, percezione dei cola negli epigrammi epigrafici in età tardoantica », Segno e Testo 8, 67-98.

Andorlini, I./Lundon, J. (2000), « Frammenti di Omero, Odissea XI 210-29 (PDuk inv. 60 + PPisaLit 23) », ZPE 133, 1-6.

Apthorp, M.J. (1980), The Manuscript Evidence for Interpolation in Homer (Bibliothek der Klassischen Altertumswissenschaften 71, Heidelberg).

Cameron, A. (1982), « The Empress and the Poet : Paganism and Politics at the Court of Theodosius II », YCS 27, 217-289.

Cavallo, G. (1965), « La scrittura del P.Berol. 11532 : contributo allo studio dello stile di cancelleria nei papiri greci di età romana », Aegyptus 45, 216-249.

Cavallo, G. (2004), « Sodalizi eruditi e pratiche di scrittura a Bisanzio », in Hamesse, J. (éd.), Bilan et perspectives des études médiévales (1993-1998) (Textes et études du Moyen Âge 22, Louvain-la-Neuve) 645-665.

Cavallo, G. (2005), Il calamo e il papiro. La scrittura greca dall’eta ellenistica ai primi secoli di Bisanzio (Pap. Flor. XXXVI, Firenze).

Cavallo, G. (2009), « Greek and Latin Writing in the Papyri », in Bagnall, R.S. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology (Oxford) 101-148.

Cribiore, R./Davoli, P./Ratzan, D.M. (2008), « A Teacher’s Dipinto from Trimithis (Dakhleh Oasis) », JRA 21, 170-191.

Davoli, P./Cribiore, R. (2010), « Una scuola di greco del IV secolo d.C. a Trimithis (Oasi di Dakhla, Egitto) », in Capasso, M. (ed.), Leggere greco e latino fuori dai confini nel mondo antico (I Quaderni di Atene e Roma 1, Lecce) 73-87.

Del Corso, L. (2008), « L’Athenaion Politeia (P.Lond.Lit. 108) e la sua “biblioteca” : libri e mani nella chora egizia », in Bianconi, D./Del Corso, L. (ed.), Oltre la scrittura. Variazioni sul tema per Guglielmo Cavallo (Dossiers Byzantins 8, Paris) 13-52.

Derda, T. (2010), P.Bodmer I Recto : A Land List from the Panopolite Nome in Upper Egypt (After AD 213/4) (JJP Suppl. 14, Warsaw).

Egberts, A./Muhs, B.P./Van der Vliet, J. (2002), Perspectives on Panopolis (Pap. Lugd. Bat. XXXI, Leiden).

Haslam, M. (1997), « Homeric Papyri and Transmission of the Text », in Morris, I./Powell, B. (ed.), A New Companion to Homer (Mnemosyne Suppl. 163, Leiden/New York/Köln) 55-100.

Kasser, R. (1988), « Status quaestionis 1988 sulla presunta origine dei cosidetti Papiri Bodmer », Aegyptus 68, 191-194.

Kasser, R. (1991), « Bodmer Papyri », in Atiya, A.S. (ed.), The Coptic Encyclopedia 8 (New York) 48-53.

Kasser, R. (2000), « Introduction », in Bircher, M. (éd.), Bibliotheca Bodmeriana (München), Tome 1, XXI-XXXVII.

Lameere, W. (1960), Aperçus de paléographie homérique. A propos des papyrus de l’Iliade et de l’Odyssée des collections de Gand, de Bruxelles et de Louvain (Les Publications de Scriptorium 4, Paris/Bruxelles/Anvers/Amsterdam).

Laplace, M. (1993), « A propos du P.Robinson-Coloniensis d’Achille Tatius, Leucippé et Clitophon », ZPE 98, 43-56.

Martin, A./Primavesi, O. (1999), L’Empédocle de Strasbourg (P.Strasb. gr. Inv. 1665-1666) (Berlin/New York).

Messeri, G./Pintaudi, R. (1998), « Documenti e scritture », in Cavallo, G./Crisci, E./Messeri, G./Pintaudi, R. (ed.), Scrivere libri e documenti nel mondo antico (Pap. Flor. XXX, Firenze) 39-53.

Messeri, G./Pintaudi, R. (2000), « I papiri greci d’Egitto e la minuscola libraria », in Prato, G. (ed.), I manoscritti greci tra riflessione e dibattito (Pap. Flor. XXXI, Firenze) 67-82.

Miguélez Cavero, L. (2008), Poems in Context. Greek Poetry in the Egyptian Thebaid 200-600 AD (Sozomena 2, Berlin/New York).

Rengakos, A. (2009), « Die Überlieferungsgeschichte der homerischen Epen im Altertum. Eine Skizze », in Karamalengou, E./Makrygianni, E. (ed.), Άντιφίληcιc. Studies on Classical, Byzantine and Modern Greek Literature and Culture. In Honour of John-Theophanes A. Papademetriou (Stuttgart) 83-91.

Robinson, J.M. (1990a), « The First Christian Monastic Library », in Godlewski, W. (ed.), Acts of the Third International Congress of Coptic Studies, Warsaw 1984 (Warszawa) 371-378.

Robinson, J.M. (1990b), « The Pachomian Monastic Library at the Chester Beatty Library and the Bibliothèque Bodmer », in Occasional Papers of The Institute for Antiquity and Christianity 19, 1-27.

Robinson, J.M. (1990/1991), « The Pachomian Monastic Library at the Chester Beatty Library and the Bibliothèque Bodmer », in Manuscripts of the Middle East 5, 26-40.

Schironi, F. (2010), TO ΜΕΓΑ ΒΙΒΛΙΟΝ. Book Ends, End-Titles, and Coronides in Papyri with Hexametric Poetry (Am. Stud. Pap. 48, Durham, North Carolina).

Schubert, P. (2002), « Contribution à une mise en contexte du Codex des Visions », in Hurst, A./Rudhardt, J. (éd.), Le Codex des Visions (Recherches et Rencontres. Publications de la Faculté des Lettres de Genève 18, Genève) 19-25.

Turner, E.G. (1980), Greek Papyri. An Introduction (2nd ed., Oxford).

Turner, E.G./Parsons, P.J. (1987), Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World (2nd ed., BICS Suppl. 46, London).

____________

1 I am most grateful to Michael Apthorp for detailed comments on my edition of the papyrus and earlier versions of this paper, and to Gianfranco Agosti for valuable discussion and a number of bibliographical references.

2 P.Duk. inv. 779 (formerly P.Rob. inv. 43) + P.Köln inv. 902 = Homer & the Papyri Od. p167 = LDAB 2074 = MP3 1033.3. The Duke fragments have been on permanent loan to the Cologne collection since 1986.

3 Fr. 3+abc, de+14+15, f+16, g+19, hi+20+21, 22+k+23, 24+l, mn+26+27. Letters refer to the Cologne, numbers to the Duke fragments.

4 This is not a mere summary of the original edition. In a few cases it has been possible to add or modify details. I have also been able to take account of several publications that have appeared or come to my notice in the meantime. I take the opportunity here to correct two of the slips pointed out to me by Michael Apthorp. In the note on Od. 3, 111, for « Die erstere » (p. 54, l. 5), read « Die letztere » (in reference to the variant ἀμύμων) and, for « Letztere » (l. 7), « Erstere » (in reference to ἀταρβήc). In the note on Od. 3, 493 (p. 65) the manuscript sigla are Ludwich’s.

5 To judge from the number of fragments of the third and fourth books of the Odyssey preserved (see the list of 18 items in P.Köln XII 468, 33-34, which however only records papyri overlapping with the Cologne pieces), the two books appear to have been quite popular reading in Graeco-Roman Egypt. The popularity of Odyssey 4 is also noted by Haslam (1997) 59. One wonders whether it was not at least in part due to Menelaus’ account of his Egyptian captivity on the island of Pharos.

6 For an image of the two fragments joined, see P.Köln XII 468, Tafel VI.

7 Schironi (2010) could only take the Cologne fragments (P.Köln I 40 = Schironi no. 46) into account in her welcome study of book-ends in papyri containing hexametric poetry. Fr. 16 now shows that she was obviously right to rule out the possibility of a versus reclamans (cf. 33, n. 81), but perhaps slightly too confident in supposing, with the first editor of the Cologne fragments, the presence of an end-title (cf. 39, 180 and P.Köln I 40, Introd. 90), unless the title was written further to the left as in P.Louvre inv. AF 12809 (= no. 19). But does the « crossed alpha flanked by two vertical strokes with a reversed triangle underneath » (cf. 122) under the last line of col. XV in this Louvre papyrus (Iliad 1, 611) really qualify as a true end-title ? Furthermore, in P.Mich. inv. 5760d (= no. 39) part of an end-title is clearly visible in the space of 8-9 lines left between Odyssey 14 and 15, but it is written in a different hand and may therefore be a later addition. According to Schironi (49-50, 52 and 82), moreover, the Cologne (and Michigan) fragments continue « the old Ptolemaic system of having one book after the other in the same column » as opposed to Roman rolls which « seem to have adopted the new system of starting a new Homeric book in a new column ». It is also to be noted here that P.Bodm. I 1 and 2 (= no. 44 and 45) do have end-titles, although this fact alone does not suffice to prove that these fragments of books 5 and 6 of the Iliad come from separate rolls (cf. 52 with n. 118, 176 and 178).

8 P.Köln XII 468 provides further evidence against the view held by some (see esp. Lameere [1960] 9-11, 39, 131, 241-243) of the independent circulation of individual books of the Homeric poems in the Roman period. On the question, see now Schironi (2010) 44, 51-52 and 81, who cites as certain examples of Roman rolls containing more than one book of Homer P.Lond.Lit. 27 (= Schironi no. 12), P.Mich. inv. 5760d (= no. 39) and our papyrus (= no. 46). To these three examples she could also have added P.Lond.Lit. 30 (= no. 17), whose two-line end-title clearly included in its first line the name of the Odyssey and in its second line wellspaced references to books 1, 2 and 3 and which must therefore originally have held the first three books of the poem. The letter taken by Schironi on p. 118 as an epsilon is in fact a beta, is preceded by an alpha and must be followed by a restored gamma. These certain cases of rolls written in the Roman period and containing more than one book of Homer should make future editors wary of automatically assigning fragments of separate books of the Homeric poems written in the same hand to distinct rolls. Some considerations against the possibility that our roll originally contained further books of the Odyssey are advanced in P.Köln XII 468, 21-22.

9 The fragments preserving parts of the upper margin show that columns began with Od. 3, 460 (Fr. de), 489 (Fr. f I) ; 4, 18 (Fr. f II +17 I), 45 (Fr. 17 II), 78 (Fr. 18), 106 (Fr. g I), 135 (Fr. g II), 164 (Fr. hi II), 193 (Fr. 22), 221 (Fr. 24 I), 251 (Fr. 24 II), 280 (Fr. 25), 339 (Fr. mn), 371 (Fr. 28) ; the fragments with remains of two consecutive columns that Od. 3, 489 and 4, 18 (Fr. f), 4, 18 and 45 (Fr. 17), 106 and 135 (Fr. g), 221 and 251 (Fr. 24) stood opposite one another. Seven columns contained 29 lines (I, II, VI, VII, VIII, XI, XIV), four 28 (III, IV, V, IX) and one 30 (X). Columns XII and XIII held together 59 lines, but which had 29 and which 30 is not clear. In columns XV und XVI alone the number of lines cannot be determined. Incidentally, as Michael Apthorp points out, since column XI would have no more lines than average with Od. 4, 273, missing in some medieval manuscripts, the column-length at least gives no support to its being an interpolation. For a table collecting the particulars about the surviving columns and a graphic reconstruction of the roll, see P.Köln XII 468, 22 and 36 respectively.

10 1344 (total number of verses in Od. 3-4) ÷ 29 (average number of lines in a column) = 46,3 columns x 7 cm (column-to-column width) = 324,1 cm.

11 Cf. P.Köln XII 468 Tafel VI (Fr. 17) : 8,5 cm (15 lines or approximately one half of the lines in a column) x 2 + 1,5 cm (surviving upper margin) + 1,5 cm (assumed minimum depth of lower margin).

12 For the variety of writing styles adopted for texts of Homer, see Haslam (1997) 60. A selection of examples in Lameere (1960) Planches 1-10 and Turner (1987) Plates 12, 13, 14 and 80. On the chancery style, see Cavallo (1965), reprinted in Cavallo (2005) 17-42, Cavallo (2009) 120-123, and Messeri/Pintaudi (1998).

13 The combination in P.Köln XII 468 thus seems to anticipate by several centuries the general adoption around 800 AD of a cursive script stylised in the chancery manner to write books (later to become standard Byzantine Greek minuscule). On this development, see Messeri/Pintaudi (2000) and Cavallo (2009) 136.

14 Cf. P.Köln XII 468 Tafel VI.

15 See P.Köln I 40 Introd., 89.

16 See Derda (2010).

17 See P.Köln XII 468 Tafel X (Fr. m).

18 See Turner (1987) 11 with n. 50.

19 See P.Köln XII 468 Tafel V (Fr. de+14+15).

20 See Cribiore/Davoli/Ratzan (2008) and Davoli/Cribiore (2010).

21 On the function of the epigrams, see Cribiore/Davoli/Ratzan (2008) 189 and Davoli/Cribiore (2010) 84 and 87.

22 High stops are also placed regularly at the ends of the distichs (I 4, 8, 12 and 16) and once (erroneously ?) also after the hexameter (I 6). At least two considerations suggest that the points occurring within the verses perform a metrical function: first, on all three occasions they are preserved, they fall invariably at the third-trochee caesura of the hexameter and, secondly, in one of these cases (I 9) the marking of a syntactical break would seem superfluous.

23 The layout of certain late antique verse inscriptions also reveals an awareness of the perceived metrical structure of the hexameter and, in distichs, the pentameter by dividing at the caesura and writing the second part of the verse indented on a fresh line, as Agosti (2010) in a study of the phenomenon convincingly argues.

24 See however Haslam (1997) 63 : « The stabilization of the 2nd century B.C., however drastic, was still only relative. Manuscripts continue to show a great deal of textual variation (more than is sometimes made out), but its range is narrower than seems to have been the case earlier. »

25 Od. 3, 51-53; 4, 49-51, 343-345, but Od. 3, 51-53 may simply be lost in a lacuna between Frr. 1 and 2. On the other hand, a few other missing verses (Od. 3, 493 and 4, 57-58), which are weakly attested in these places, occur elsewhere in the Homeric poems and whose omission cannot be explained mechanically, were almost certainly absent in the exemplar. The papyrus thus provides further evidence that they are interpolations. Cf. Apthorp (1980) 221, n. 29 on Od. 3, 493 and 20-21 on 4, 57-58. As to Od. 3, 78, missing in the two other papyri and occurring in a minority of the medieval manuscripts, it cannot be quite ruled out that it was absent from the papyrus, although the traces appear to suggest its presence. In addition to inadvertently dropping verses, moreover, the copyist seems once to have mistakenly repeated one (Od. 4, 21a).

26 Od. 4, 339 (τοιvсι‹ν›), 340 (Οδυс{с}ευс), 342 (εωс for εων), 349 (‹ε›ειπε), 351 (Α̣ιγυπτω {δε} μ’ ετι δευρο θ̣[εοι μεμαωτα νεεсθαι]). In at least one case, the same mistake occurs in the papyrus as in a later manuscript (Od. 3, 145 : ἐξακέсαιο for ἐξακέсαιτο).

27 The other unattested variants : 3, 152 (κακοῖсιν for κακοῖο) and 4, 281 (ἀκούομεν for ἀκούсαμεν). To these may be added 3, 467 (χλαίναν καλὴν for φᾶροс καλὸν) and 496 (ὑπεξέφερον πόδεс ἵππων for ὑπέκφερον ὠκέεс ἴπποι), where apparently formular expressions occurring elsewhere in the Homeric poems have been exchanged.

28 See P.Köln XII 468 Tafel II (Fr. 1).

29 Some of the weakly attested variants (τὸν at 3, 239 or πρίν γ’ at 4, 254) seem also to imply reasoning and may too derive from conjectures.

30 For another apparent conjecture in an Odyssey papyrus probably involving the dual, see Andorlini/Lundon (2001) 4-5.

31 Rarely attested variants : 239 (τὸν for τὴν) ; 4, 20 (ἵπποι for ἵππω), 254 (πρίν γ’ for πρίν), 287 (χειρὶ for χερcὶ). More or less well-attested variants rejected by some or all of the editors : 3, 111 (ἀμύμων for ἀταρβήc), 182 (ἔcταcαν for ἵcταcαν), 204 (ἀοιδήν for πυθέcθαι), 490 (ὁ δὲ τοῖc πὰρ ξείνια θῆκεν for ὁ δ’ ἄρα ξεινήϊα δῶκεν) ; 4, 19 (μέccουc for μέccον), 115 (ὀφθαλμοῖcιν for ὀφθαλμοῖιν), 119 (μυθήcαιτο for πειρήcαιτο), 251 (ἀνειρώτευν for ἀνηρώτων, ἀνηρώτευν, ἀνειρώτων), 252 (ἐγὼν ἐλόευν for ἐγὼ λόεον), 254 (μὴ μὲν for μή με), 282 (ὁρμηθέντε for ὁρμηθέντεc). A few of these (ἀμύμων at 3, 111 ; ὁ δὲ τοῖc πὰρ ξείνια θῆκεν at 3, 490 ; μυθήcαιτο at 4, 119) are regarded by the scholia explicitly or implicitly as inferior readings.

32 For a recent sketch of the transmission of the Homeric poems in antiquity, see Rengakos (2009).

33 See P.Köln I 40 Introd., 89 and P.Köln XII 468 Introd., 24-26 and 30-31.

34 Listed in the order of the Cologne inventory numbers : P.Köln inv. 901 + P.Duk. inv. 772 (P.Rob. inv. 35) : Achilles Tatius, Leucippe and Clitophon (LDAB 8, MP3 0002.100) ; P.Köln inv. 902 + P.Duk. inv. 779 (P.Rob. inv. 43) : Homer, Odyssey 3 and 4 (LDAB 2074, MP3 1033.3) ; P.Köln inv. 903 a-k + P.Duk. inv. 774 (P.Rob. inv. 37) : Unknown Prose (LDAB 4651, MP3 2580.010) ; P.Köln inv. 904 + P.Duk. inv. 775 (P.Rob. inv. 38) + P.Bodm. IV, XXV, XXVI : Menander, Samia, Dyscolus and Aspis (LDAB 2743, MP3 1298) ; P.Köln inv. 905 + P.Duk. inv. 773 (P.Rob. inv. 36) + P.Gen. inv. 272 : Plutarch, Life of Caesar (LDAB 3842, MP3 1431); P.Köln inv. 906 + P.Duk. inv. 769 (P.Rob. inv. 32) : Scholia Minora to Homer, Odyssey 1, 45-116 (LDAB 1949, MP3 1207.2) ; P.Köln inv. 907 + P.Duk. inv. 777 (P.Rob. inv. 40) + P.Gen. inv. 271: Cynic Diatribes (LDAB 3866, MP3 2580). The ranges of the inventory numbers of the various collections (P.Köln inv. 901-907 ; P.Duk. inv. 769-779 (P.Rob. inv. 32-43) ; P.Gen. 271-272) also show that the papyri belong to sets acquired together and deriving from the same source.

35 Turner (1980) 52-53, within a discussion of the provenance of the Menander codex P.Bodm. IV, refers to this fact as evidence that the codex might come from Panopolis.

36 Robinson (1990a, 1990b and 1990/1991), who includes both the two Bodmer Iliad rolls and the Cologne Odyssey papyrus in his inventory of the contents of the find (nos. 1, 2 and 37 = 35 = 32), argues that the texts formed the library of the Monastery founded by Pachomius in Upper Egypt in the fourth century, were unearthed in 1952 in the plain of Dishna, where they had been buried in a jar in the seventh century, and came through middlemen and dealers into the possession of various collections, the principal of which are the Bodmer and Chester Beatty libraries. He accounts for the presence of non-Christian Greek literary texts by supposing they were « gifts from outside, perhaps contributed by prosperous persons entering the Order » ([1990b] 4-5). Details of this reconstruction have been handled with varying degrees of scepticism by Kasser (1988, 1991 and 2000). Along the lines of Robinson, Agosti (2001 and 2002) believes that the Bodmer papyri represent the library of a monastic community, some of whose members shared an interest in Greek literature. Laplace (1993) 53-55, on the other hand, taking up suggestions by V. Martin, J. Van Haelst and J.-L. Fournet, among others, sees in these papyri the collection of a school in Panopolis, which, originally pagan, later converted to Christianity.

37 For literary papyri written in chancery hands and so apparently copied by functionaries, cf. Messeri/Pintaudi (2000) 81-82 and Cavallo (2009) 123. A further clue that this may well have been the case of P.Bodm. I is the fact that the literary texts (Iliad 5 and 6) are written on the back of an administrative roll.

38 For a definition of this concept, see Cavallo (2004) 646 and Del Corso (2008) 14.

39 See Cameron (1982) 217-221, Martin/Primavesi (1999) 43-51, Egberts/Muhs/van der Vliet (2002), Schubert (2002) and Miguélez Cavero (2008) 191-263.

40 See Martin/Primavesi (1999) 51, who date the papyrus to the latter part of the first century AD (p. 15). The pillars in the garden of Ptolemagrius at Panopolis, inscribed with Greek poetry and also dating perhaps to the first century AD (cf. Cameron [1982] 219-220), point in the same direction.

41 On the poets coming from Panopolis and vicinity, see Cameron (1982) 217-221. To the Ammon archive belong fragments of a papyrus codex with parts of Odyssey 9 and 11 (P.Ammon II 26) and possibly also a glossary on Odyssey 1 (P.Köln IX 362; cf. ibidem p. 56 n. 10).

42 On the names of some teachers, see now Miguélez Cavero (2008) 214-218.