Athletes and liturgists in a petition to Flavius Olympius, praeses Augustamnicae

The main Greek text on this only partly preserved Vienna papyrus is addressed to Flavius Olympius, who may be identified as the praeses of the Augustamnica attested for AD 343. The sender is Aurelius Sar-, from the amphodon of Apollonios in, probably, Herakleopolis. He says that he has been making expenditures for gymnastic training (9) and may be a victorious (former) athlete himself (7, n.). Perhaps he holds a liturgical office, since the mention of such a function is expected in the lacuna before τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουργοῦν]|τοс ἀμφόδου Ἀπολλωνίο[υ (see 3-4, n.). Some elements in the text point to a petition, like the reference to a law (5), κα̣θ’ ὁμοιότητα τῶ̣[ν ἄλλ]ω̣ν ἐ̣τι̣ ἄνωθεν (11), while ἠπείχθη̣[ν (18) is the possible beginning of an expression known from other petitions2.

Since the petition was addressed to the praeses of the Augustamnica, the text may stem from the archive of this praeses3. The official residence of the praeses Augustamnicae was the capital city of the newly created province of Augustamnica: Pelusium. There are, however, hardly any papyri originating from the eastern part of the Delta, apart from carbonized texts, and no papyri at all seem to have been found at Pelusium. The papyrological testimonia for Pelusium, as far as can be known, were found at places other than Pelusium itself4. Moreover, none of the papyri mentioning the Augustamnica were found in the eastern Delta5. Perhaps the archive to which this papyrus belonged was moved to a different place after the owner retired.

The text forms part of a τόμοс сυγκολλήсιμοс; the remains of a different document are visible at the left side of the papyrus. This way of archiving documents by pasting them together into rolls was recently studied by Willy Clarysse6. Like most other τόμοι сυγκολλήсμοι this τόμοс contains the original text (as shown by the layout and larger lettering of the address and the different handwriting of the two texts left of the τόμοс), and the text comes from an official background (the petitioner may be a liturgist of the amphodon of a city, see 3-4, n.). Clarysse observed that this archiving practice, stemming from Ptolemaic times and most popular among higher as well as lower officials during the Roman period, came to an end in the middle of the fourth century AD. The present text, of around 343, is now the latest example of a τόμοс сυγκολλήсιμοс.

Most interesting in this document is the subject around which it revolves: mention is made of a victory (6: νίκηс), of victors (7: сτεφανντ̣ῶν̣; 13: сτεφανιτ̣[), of training for the gymnastic game (8: ἄсκηсιν τοῦ γυμνικοῦ̣ ὐγῶνοс) and of expenses made on training and practice (9: ἀναλώματα πεποίημαι εἰc ἄcκ̣ηсιν καὶ ἄθληсιν). The word for «athlete» or again «practice» is partly preserved in line 16: ἀθλη[. In line 14 [δω]ρηθέντα, in combination with the preceding τῇ θεοφιλεс]|τάτ̣ῃ εὐεργεсίᾳ τῶν ἀνθρωπῶν, may point to games granted by an emperor. It appears from the text that the petitioner was very much involved in gymnastic training for games (he even spent money on it [9]), but it remains uncertain if he was a (former?) athlete himself. Is the νίκη referred to in line 6 the petitioner’s own victory or someone else’s? May it be inferred from ἄλλων (7) that the petitioner himself was a victor, too? The petitioner’s son, in any case, was a victorious athlete: one can read νεν̣ικηκ̣ότα ἐ̣[ν] ἀγῶсι υἱόν μου (15).

This athletic context is all the more remarkable since by the middle of the fourth century the ancient games had gradually become less popular and started to disappear (the last official Olympic games were held in AD 393), so that information on games and athletes from that period has become very scarce.

What is the petition about? One is reminded of the third century athletes’ petitions which were mostly directed to a city council (of Hermopolis or Oxyrhynchus; no athletes were earlier known for Herakleopolis). These petitions dealt with the confirmation or registration of an athlete’s privileges7. The present petition, however, which does not necessarily stem from an athlete, appears to deal with a different problem and was directed to the higher level of the praeses.

Based on so few and such uncertain facts, one can only speculate as to the contents of the petition. There is not much that can be known for certain:

– the petitioner undertook something (4: ἐνεχείρηсα), paid for athletic training (9), his son had won in games (15);

– there is a general context of games and athletes (see above) and of an event that took place abroad (6: ἀλλο̣δ̣απῆc);

– reference is made to a list of nominations to liturgies (16: γραφῆc λειτο̣υ̣ρ̣γ̣ῶν).

Hypothetically, this may be a petition against appointment to a liturgy, from someone who was appointed while he was away from home, claiming exemption on the grounds that he is a victor in the games and has already spent a lot of money on athletic training8. If we assume that the petitioner already was a liturgist (see 3-4, n.), he might be petitioning against a second appointment9. In both cases, the reference to «today’s list of liturgists» (16) may have been needed to substantiate the complaint.

Speculating even further: accepting the slight chance that the petitioner is indeed identical with Sarmates son of Pamounis of PSI XII 1232 (cf. 3, n.) and thus a systates, he would himself be responsible for the list of nominations. He may then have appended the list to his petition (or even the petition to his list), because the petition dealt with a problematical appointment. In this scenario the petitioning systates could hardly be petitioning against his own nomination for a liturgical office. Perhaps he was instead asking to be released from his post since he had taken up all the athletic obligations mentioned. Other scenarios are possible and nothing can be certain on the basis of the all too fragmentary text.

However the case may be, this text shows at least one important thing: how the ancient Greek games still played a role in the society of early Byzantine Egypt, even as late as the middle of the fourth century AD10.

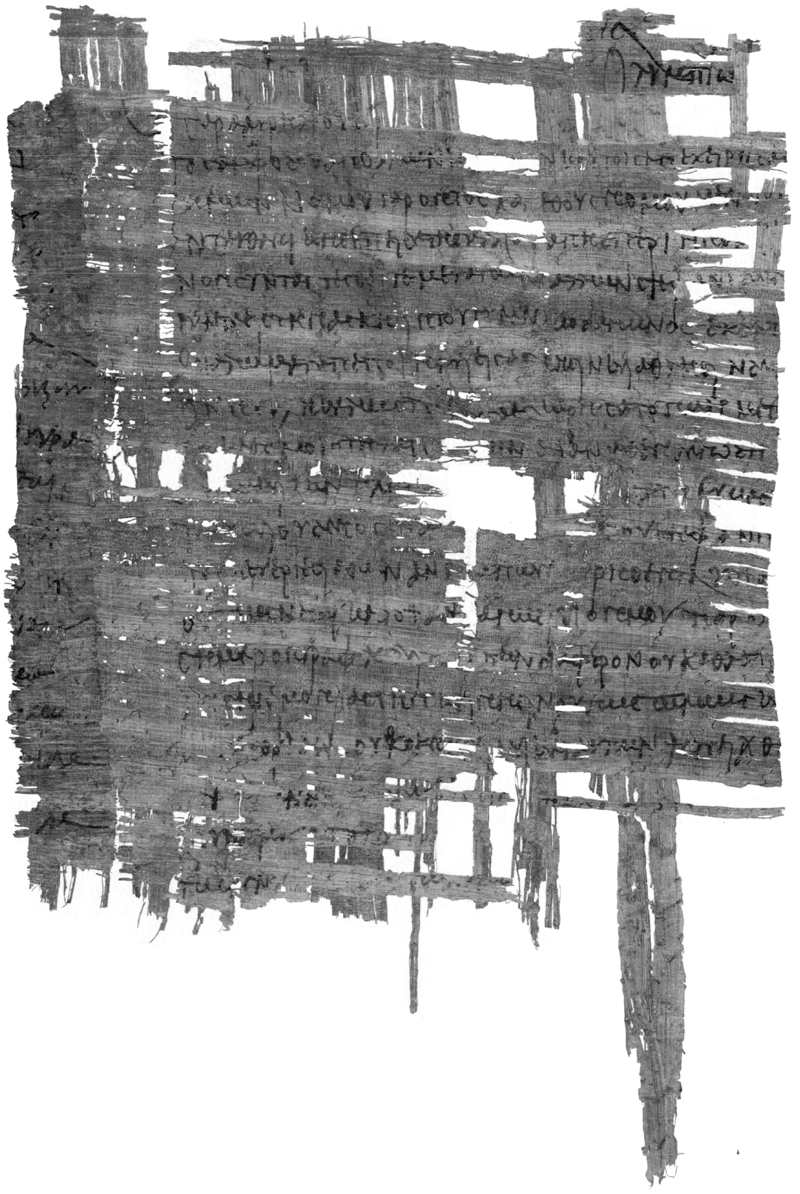

P.Vindob. inv. G 24715

| P. Vindob. inv. G 24715 | 22,2 x 14,5 cm | ca. AD 343 written in Herakleopolis (?)/ found in Pelusium (?) |

Part of a τόμοс сυγκολλήсιμοс; at the left side, the ends of 16 lines of a different document remain11. One kollema is visible at ca. 1,5 cm from the left side. There is a free margin of 1,5 – 2 cm between the kollema and the text on the right-hand side. The dark brown color of the right-hand sheet of papyrus is interspersed with lighter strips at regular intervals, which may point to the manufacturing of the papyrus according to the «Hendriks» method12. The papyrus is broken off at all sides and the whole sheet is rather damaged, with a larger hole in lines 11-13. Not much seems to be missing from the top, but probably almost half of the text of the main document is missing on the right-hand side13; looking at the longest vertical strip preserved, at least a third of the document is lost at the bottom. The largest remaining text in this τόμοс сυγκολλήсιμοс consists of 21 lines of Greek, written along the fibers in a neat, experienced professional hand. At the start of each line the writer wrote slightly larger initial letters. Large stylish script was used for the address in line 2. Some characters have small superfluous loops (e.g. 18: κ of οὐκ; χ of ἠπείχθη̣[ν) or end-strokes striking through the next character (e.g. 4: εν of ἐνεχείρηсα; 5: δη of δημῶν; 17: ωс of οὕτωс). Sometimes a prolonged downward stroke of rho or iota reaches, or even crosses, the writing of the next line (e.g. 14: ρ of ἀνθρωπῶν through 15: ἐ̣[ν]; 16: ρ of cήμερον through 17). The traces in line 1 are possibly Latin. The overall impression of the handwriting points to the fourth century AD, which is not contradicted by the more cursive handwriting of the line endings of the text on the left14. The verso is blank. Based on the contents, the text was possibly written in Herakleopolis and probably archived at Pelusium, but may have been found elsewhere.

.[ ].[ ]... .q. .[ [Φλ]α̣ο̣υ̣ί̣ω̣ι̣ vacat Ὀλυμπίωι̣ [ vacat παρὰ Αὐρηλίου С̣α̣ρ̣[- father’s name, city, function (?) τοс ἀμφόδου Ἀπολλωνίο[υ. τη]λ̣ι̣κούτοιс ἐνεχείρηсα.[ 5 δημῶν, νόμου γὰρ ὄντοс καὶ ἔθουс, νόμου μὲν̣… [ ἐνταῦθα νίκηс. ἐπεὶ δὲ τῆc ἀλλο̣δ̣απῆc περιγινο̣μ̣[ένηс νον сυντάττεсθαί τε μετὰ τῶν ἄλλων сτεφανιτ̣ῶν̣ [ сαντα εἰc τὴν ἄсκηсιν τοῦ γυμνικοῦ ἀγῶνοс ἐκ δὲ τ[ ἀναλωματα πεποίημαι εἰc ἄсκηсιν καὶ ἄθληсιν δε.[ 10 ὃν ἡ τ̣ύχη καλῶc πο̣ιο̣ῦсα ἐδωρήсατο τῷ ἡμετ[έρῳ .. καθ’ ὁμοιότητα τῶ̣[ν ἄλλ]ω̣ν ἐτι ἄνωθεν, λέγω δὴ [ … δὲ καὶ τὴν γ̣λ̣..[ ± 15]. c̣υ̣νεχῶ̣c c̣[ τ.ν̣ καὶ οὐδένοс ..α[ ± 12].ου сτεφανιτ̣[ τάτ̣ῃ εὐεργεсίᾳ τῶν ἀνθρώπων [δω]ρηθέντα ὑπὸ [ 15 οὕτωс νεν̣ικηκ̣ότα ἐ̣[ν] ἀγῶсι υἱόν μου παρόν̣[τα cήμερον γραφῆc λειτο̣υ̣ρ̣γῶν διαφέρον οὐκ ἀθλη[ τῃc ἡγεμονίαс τὴν κείνηсιν οὕτωс ὠμῶc κ[ [..]. θρίαν̣ οὐκ ὀκνήcε̣ι μοι κατ’ αὐτῶν. ἠπείχθη̣[ν .[…].νδ.[…..]………[…]…………[ 20 κ̣ο̣ύτ̣ο̣υ̣ μο̣.π̣π̣..[.]ρ̣[ τω.сν[………]τ̣ω… [ |

] τῷ διαсημοτάτῳ ἡγεμόνι] τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουργοῦν-] ἀπο(?)-] ] ] ἀναλώ-] ] ] ] ] ] τῇ θεοφιλεс-] ] ] τῆc cῆc διαсημοτά-] ] ] τηλι-] ] ] |

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. | |

6 περιγιγνομένηс 8 γυμνικοῦ̣: υ̣ corr. ex α? 17 κίνηсιν

(…) (Latin notation?). To Flavius Olympius the most eminent praeses, from Aurelius Sar- (father’s name, city, function?) of the amphodon of Apollonios which is currently providing liturgists. With such great (…) I undertook (…) [5] while I was away from home, because it is the law and the custom, the law (…) victory there. Since of the elsewhere resulting (…) and to order with the other victors (…) having paid for the training of the gymnastic games and from (…) I made expenses on training and practice (…) [10] which the good fortune, acting well, presented to our (…) in the same way as the others already for a long time, I mean (…) and the (…) continually (…) and nobody (…) victor(s) (…) with the most god-loved well-doing towards the people granted by (…) [15] thus my son, having won in games, being present (…) of today’s list of liturgists not pertaining to athletes/practice (…) of your most eminent praeses-ship the movement thus cruelly and (…) he shall not hesitate for me against them. So I was forced to (…) [20] of such a great (…).

1 .[ ].[ ]..q..[. Probably traces of Latin, since a q may perhaps be recognized. Perhaps a short remark in Latin was added afterwards at the officium of the praeses, possibly some (abbreviated?) archival notation. At the start of this line, there must have stood a large letter of which the extended lower part, curving to the right, is still visible in the margin before 3. Note that the vertical traces at the right end of the papyrus form the upper parts of the two iotas of Ὀλυμπίωι in line 2 underneath.

2 [Φλ]α̣ο̣υ̣ί̣ω̣ι̣ vacat Ὀλυμπίωι̣ [. Of α̣ο̣υ̣ only traces of the upper part of the characters remain. In view of τῆс сῆс διαсημοτά]|τ̣η̣c̣ ἡγεμονίαс (17), the addressee may be identified as Flavius Olympius, who is attested as praeses Augustamnicae in four other papyri. He is the addressee of a petition published by Emmett (1984), now known as SB XVI 12814 (Herakleopolites, ca. AD 343) with the heading Φλαουίω Ὀ̣λυμπίωι τῷ διαсημοτάτῳ ἡγ̣[εμόνι. The present text is accordingly supplemented with τῷ διαсμοτάτῳ ἡγεμόνι, which was probably preceded by another blank space. Flavius Olympius is further mentioned as praeses of the Augustamnica in SB VI 9622 (= P.Sakaon 48; Theadelphia; 6 April, AD 343), the only attestation also figuring in PLRE I, s.v. «Olympius 15»; P.Oxy. XLVIII 3389 (14 March, AD 343); P.Oxy. LXII 4345 (AD 343). A list of praesides Augustamnicae is provided by Palme (1998), where on page 134 can be found that the predecessor of Flavius Olympius, and first praeses Augustamnicae, was Flavius Iulius Ausonius with last dated attestation of 1 July 342 (P.Oxy. LIV 3775); the first successor known was Flavius Areianus Alypius, in office on 5 July 351 (CPR V 12). These dates provide the termini post and ante quem for the present text.

3 παρὰ Αὐρηλίου С̣α̣ρ̣[. After the sender’s name, his father’s name is expected, followed by the sender’s origin (possibly Herakleopolis, see below, 3-4, n.) and probably a liturgical function preceding τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουργοῦν]|τοс ἀμφόδου (see below, ibidem). It cannot be excluded that Aurelius Saris identical with Aurelius Sarmates, systates of Herakleopolis, the sender of the petition PSI XII 1232, 2-5 (Herakleopolis, IV AD): παρά Αὐρηλίου С̣α̣ρ̣μ̣άτου Παμο̣ύ|νιοс сυсτάτου τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουρ|γοῦωτοс ἀμφόδου Ἀπολλωνίου τῆc αὐτῆc πόλεωс One should, however, keep in mind that both readings of the name Sarmates are uncertain. This identification, if correct, would also mean that the date of PSI XII 1232 could be narrowed to around AD 343. The function of systates, one of whose duties was the nomination to liturgies, might well fit the context of both τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουργοῦν]τοс and of cήμερον yραφῆc λειτο̣υ̣ρ̣γῶν in line 16 of this text. On the systates, see Van Minnen in P.Lugd. Bat. XXV, p. 275-276; on liturgies, see Lewis (1992); see also below 16, n. If at all accepted, the supplement of 3-4, παρὰ Αὐρηλίου С̣α̣ρ̣[μάτου Παμούνιοс ἀφ’ Ἡρακλέουс πόλεωс сυсτάτου τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουργοῦν]|τοс ἀμφόδου Ἀπολλωνίου, would give a total line length for the whole text of about 72 letters and the missing right part of the papyrus will have contained about 33 letters per line. That τῆc αὐτῆc πόλεωс of PSI XII 1232 is not found in the present text may be explained by the fact that in this case the addressee is in a different city, so the sender’s city would already be included in his own description (ἀφ’ Ἡρακλέουс πόλεωс and did not need to be repeated here.

3-4 τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουργοῦν]|τοс ἀμφόδου Ἀπολλώνίου. An ἂμφοδον Ἀπολλωνίου is attested for the cities of Arsinoe, Oxyrhynchus and Herakleopolis, all situated in the Augustamnica at the time of Flavius Olympius (attestations in the Database of Placenames, s.v. «amphodon Apolloniou», January 2011). In Arsinoe, however, there are actually two amphoda of the same name, always distinguished from each other by adding either Παρεμβολῆc or Ἱερακείου after Ἀπολλωνίου; see Reiter (2002) 129. This is not the case here. For Oxyrhynchus there is only one exceptional attestation, P.Oxy. XIV 1695, 14 (AD 360); see Del Fabbro (1982) 15-17. This would result in Herakleopolis as the city in question for this amphodon. For the Herakleopolite amphodon Apolloniou, see Calderini/Daris, Diz. geogr. I.2, p. 153-154, s.v. Ἀπολλωνίου 4, with Suppl. 1, p. 47 and Suppl. 4, p. 17 (and Database of Placenames). Before ἀμφόδου Ἀπολλωνίου̣, the only possible supplement which ends in -τοс seems to be τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουργοῦν]τοс: «of the amphodon of Apollonios which is currently providing liturgists» (DDbDP, January 2011). The expression τοῦ νυνὶ λειτουργοῦντοс is found in two papyri, from the third (?) and fourth century respectively; in both cases it is followed by ἀμφόδου Ἀπολλωνίου, and both texts originate from Herakleopolis: BGU III 958c, 11-13 and PSI XII 1232, 3-5 (cited above, 3, n.).

4 ἐνεχείρηсα. From the verb ἐγχειρέω «to take in hand», «undertake», «attempt», originally with dativus rei, but later and in papyrological documentation normally with accusativus rei; cf. LSJ s.v. If the word was written with iotacistic eta instead of iota, the form may also have come from ἐγχειρίζω «put into one’s hands». The latter might seem attractive because this verb is often connected to liturgies; but see Lewis (1997) 59: «In the context of liturgy this verb is found only in the passive (“the office assigned to me” aut sim.).» So there is no special connection between the verb used here and liturgies. Ἐγχειρέω, according to Lewis, does not appear in the language of liturgy at all. Instead of ἐνεχείρηсα, also the middle form ἐνεχειρηάμ̣[ην, the plural ἐνεχειρήαμ̣[εν or any other form with -сα may have stood here.

4-5 ἀπο]|δημῶν. The supplement was chosen in view of ἀλλο̣δ̣απῆc (6); also possible are e.g. ἐπιδημῶν or ἐκδημῶν.

5 νόμου γὰρ ὄντοс καὶ ἔθουс For laws pertaining to athletes’ privileges, including exemption of liturgies, see Amelotti (1955). On ἔθοс «custom», see Schmitz (1970), esp. 73ff.: «Tὸ ἔθοс als Grundlage von Liturgie und Zwangsarbeit».

5-6 νόμου μὲν̣… [(…)]| ἐνταῦθα νίκηс Perhaps μὲν̣ τ̣ο̣υ̣[ can be read. Some laws on athletes mention, for obtaining certain privileges, the condition that a victory was to be won at important games in a certain place; none of them, as far as known, seem applicable in the (unclear) case of the present text; see Amelotti (1955) 352-355. Ἐνταῦθα, if meaning «there», is taken up by the following ἀλλο̣δ̣απῆc «belonging to another land» (LSJ s.v.), «from elsewhere»; if ἐνταῦθα means «here», it is contradicted by it.

6 ἀλλο̣δ̣απῆc περιyινο̣μ̣[ένηс (l. περιγιγνομένηс. The verb περιγίγνομαι is in the papyri mostly used in the meaning of «to remain», «to be left over», «to be a result or consequence». With respect to the preceding ἐνταῦθα νίκηс one might perhaps supplement the same word νίκηс after τῆc ἀλλο̣δ̣απῆc περιγινο̣μ̣[ένηс: literally «of the from elsewhere resulting victory», pointing to a victory won at games held abroad.

7 сυντάττεсθαί τε. The infinitive should depend on a main verb in the lacuna of the preceding line. Because of τε, a corresponding infinitive is also to be expected there.

μετὰ τῶν ἄλλων сτεφανιτ̣ῶν̣. A person (the petitioner himself, or possibly his son?) «is ordered» (сυντάττεсθαι) (to do something) «together with the other victors». From the word ἄλλων one may infer that this person was a сτεφανίτηс himself. Instead of μετά, με τά would also be possible, with με complementing ἀναλώ]сαντα.

сεφανντ̣ῶν̣ (and 13, сτεφανιτ̣[). «Victors». The history of the meaning of сτεφανίτηс was recently studied by Sofie Remijsen (2011). I thank Sofie Remijsen for putting the proofs at my disposal before the article was printed. She states that сτεφανίτηс originally only used as an adjective denoting a special kind of games, was, until the middle of the first century BC, never used for people. When сτεφανίτηс then came to be used (as an archaism with no special technical meaning) for members of the international associations of athletes and performing artists, it was only within this context and always preceded by the word ἱερονίκηс In the fourth century AD, сτεφανίτηс started to be used as an independent word for «victor». Remijsen, for this phenomenon, could only cite agonistic metaphors of Christian authors; the present text now provides the first attestation of this independent use of сτεφανίτηс for «victor» in a papyrus document.

8 ἄсκηсιν. See below 9, n.

γυμνικοῦ̣ ἀγῶνοс «Athletes’ games», as opposed to those of dionysiac artists, musicians, and games with horses and chariots. The same expression is attested in SPP XX 69, 6 (= Pap. Agon. 7; Hermopolis, AD 268): γυμνικοῦ Ὀλυμπικοῦ ἀγῶvoc; P.Coll. Youtie II 69, 7-8 (= Pap. Agon. 9; Oxyrhynchus, AD 272); this is part of a long description of the Capitoline games.

ἐκ δὲ τ[. Perhaps supplement ἐκ δὲ τ[οῦ ἰδίου or ἐκ δὲ τ[ῶν ἰδίων, «and from my own (means)».

9 εἰc ἄсκηсιν καὶ ἄθληсιv. The two words may here both be used for the physical training and practice of athletes. Ἄсκηсιс is found in the papyri for all kinds of practice, among which also «athletic practice»; see PSI XIV 1422, 29 (III AD). The participle ἀсκήсαс appears in P.Oxy. XXVII 2477, 6 (III/IV AD). Ἄθληсιс is found in two papyri, the first one referring to the practicing of music; see P.Lond. VII 2017 (241/242 BC) and the second to «athletics»; see SPP V 119 verso iii, 13 (Hermopolis, AD 267; translated thus in Sel. Pap. II 217): ἀ[νδρ]ῶν εὐδοκίμων κατὰ τὴν ἄθληс[ιν] γενομένων. With the meaning «athletics», «athletic profession», ἄθληсιс is often attested in inscriptions; see Searchable Greek Inscriptions (January 2011), s.v.

δε.[. Read perhaps δὲ τ̣[οῦ or δὲ τ̣[ῶν as the beginning of an article, followed by person(s) who received the training. At the end of the lacuna perhaps supplement cέφανον?

10 ἡ τ̣ύχη. With the same meaning of «the good fortune» also found in e.g. P.Ammon I 3, iii 16 (Alexandria, AD 348); SB III 6222, 36 (private letter of athlete, Alexandria, late III AD); SB XIV 11717, 30 (Hermopolis, mid-IV AD).

καλῶc πο̣ιο̣ῦсα. See P.Oxy. LIV 3758, 51 (AD 325) for the same expression, but used for a person, in a further incomplete line from proceedings before the logistes.

τῷ ἡμετ[έρῳ. Perhaps supplement υἱῷ (see 15)?

11 τῶ̣[ν ἄλλ]ῶ̣ν. Also possible τῶ̣[ν αὐτ]ῶ̣ν. Possibly referring to the сτεφανῖται (7) and/or to κατ’ αὐτῶν (18).

12 γ̣λ..[. Or τ̣λ̣..[.

13-14 τῇ θεοφιλεс]|τάτ̣η̣ εὐεργεсίᾳ. Used for emperors; supplemented from PSI XIV 1422, 32 (III AD), a petition of an athlete to the emperors.

14 [δω]ρηθέντα. Verb often used for royal grants (of privileges or games) of an emperor to his people; see Frisch (1986) 133. Supplementing [εὑ]ρηθέντα would be another, less probable, possibility.

15 oὕτωс νεν̣ικηκ̣ότα ἐ̣[ν] ἀγῶсι υἱόν μου. Since an article is lacking before υἱόν, the word νεν̣ικηκκ̣ότα should be connected with υἱόν.

16 cήερον γραφῆc λειτο̣υ̣ρ̣γῶν. «Today’s list of liturgists». Providing a yearly list of people nominated for liturgies formed part of the task of a systates. For the possibility that the sender of this petition was a systates, see above 3, n. In Herakleopolis, where this petition was probably written, as in Oxyrhynchus on which we are better informed, the liturgies were filled by different quarters of the city in annual rotation (see 3-4, n.). The systates of the quarter due to serve, himself also a liturgist, had the duty to write the γραφὴ λειτουργῶν. A table of γραφαὶ λειτουργῶν can be found in Lewis (1997) 114, with only one attestation from the fourth century AD (P.Cairo Preis. 20; Hermopolis, AD 356/357). For the fourth century it is not clear to whom these lists should be directed; some nominations are addressed to the nome logistes; see Lewis (1997) 86. The addressee would not normally have been the praeses, to whom the present petition including the reference to «today’s list of liturgists» was sent. Still, a praeses sometimes appears to be involved with these nominations: see P.Oxy. LXII 4345 (AD 343), an incomplete text about the nomination of an ἀπαιτητήc where, remarkably, «the appointment seems to have been in some manner pre-arranged with the praeses Augustamnicae Flavius Olympius» (P.Oxy. LXII 4345, introd.).

οὐκ ἀθλη[. Supplement ἀθλή[сει or ἀθλη[ταῖc.

17 κείνηсιν (l. κίν-). «Movement», «setting… in motion», «punitive action»?

ὠμῶc. Not previously attested in papyrological documents. If this is not a writing error for ὅμωс (a mistake not really expected in this otherwise well spelled text), it must be the adverb of ὠμόc, «raw, crude», probably used in a metaphorical way: «cruelly».

18 [..], θρίαν. Perhaps νωθρίαν «sluggishness, indolence», or ἐχθρίαν «hatred, enmity» (the only substantives with -θρια- found in the DDbDP, January 2011). Probably not the adjective ὀλέθριαν, since this has no feminine form (at least in papyrus documents; a feminine form is used in literature, see LSJ s.v.).

οὐκ ὀκνήcε̣ι. It is also possible to read ὀκνῆcα̣ι, but if the infinitive were part of a request «not to hesitate», one would rather expect μή instead of οὐκ.

ἠπείχθη̣[ν. For a possible supplement, see e.g. the petitions P.Merton II 91, 16 (directed to the praeses Aegypti Herculiae; Karanis, AD 315): ἠπείχθην οῦν τὴν καταφυγὴν ποιήсαсθαι πρóc сοὺс coῦc τοῦ ἐμοῦ κυρίου πóδαс δεópενoc καὶ παρακαλῶν; or P.Oxy. XLIII 3116, 17-19 (= Pap. Agon. 10, petition of a victor in the games; AD 275/276): ἠπίχθην (l. ἠπείχθην) τὴν τῶνδε τῶν βιβλει̣[δί]ων (l. βιβλιδίων) ἐπίδοсιν πoιή[сαсθ]α̣ι̣ ἀ̣ξ̣ι̣ῶ̣ν (…).

Bibliography

Amelotti, M. (1955), «La posizione degli atleti di fronte al diritti romano», SDHI 21, 123-156.

Clarysse, W. (2003), «Tomoi Synkollēsimoi», in Brosius, M. (ed.), Ancient Archives and Archival Traditions: Concepts of Record-Keeping in the Ancient World (Oxford) 344-359 with <http://www.trismegistos.org/arch/index.phbibl> (January 2011).

Carrez-Maratray, J.-Y. (1999), Péluse et l’angle oriental du Delta égyptien aux époques grecque, romaine et byzantine (Bibliothèque d’étude 124, Le Caire).

Database of Placenames of Graeco-Roman Egypt (January 2011): <http://www.trismegistos.org/geo/index.phbibl>.

Del Fabbro, M. (1982), «Note a papiri ossirinchiti», Stud. Pap. 21, 15-22.

DDbDP (January 2011) = Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri: <http://www.papyri.info>.

Drew-Bear, M. (1988), «Les athlètes d’Hermoupolis Magna et leur ville au 3e siècle», in Proceedings of the XIIIth International Congress of Papyrology, Athens 1986 (Athens) II 229-235.

Emmett, A.M. (1984), «An Unpublished Petition to Flavius Olympius (PMacquarie Inv. 358)», in Atti del XVII Congresso Internazionale di Papirologia, Napoli 1983 (Napoli) III 825-828.

Feissel, D./Gascou, J. (éd.) (2004), La pétition à Byzance. XXe Congrès international des études byzantines, 2001 (Paris).

Frisch, P. (1986), Zehn agonistische Papyri (Pap. Col. 13, Opladen).

Harrauer, H. (2010), Handbuch der griechischen Paläographie (Bibliothek des Buchwesens 20, Stuttgart).

Hendriks, I.H.M. (1980), «Pliny, Historia Naturalis XIII, 74-82 and the Manufacture of Papyrus», ZPE 37, 121-126.

Hendriks, I.H.M. (1984), «More about the Manufacture of Papyrus», in Atti del XVII Congresso internazionale di papirologia, Napoli 1981 (Napoli) I 31-37.

Hoogendijk, F.A.J./Worp, K.A. (2001), «Drei unveröffentlichte griechische Papyri aus der Wiener Sammlung», Tyche 16, 45-61.

Kramer, B. (1987), «P.Strasb. Inv. 1265 + P.Strasb. 296 recto: Eingabe gegen ἀνδραπoδιсpóc (= plagium) und cύληсιс (=furtum)», ZPE 69, 143-161.

Lewis, N. (1992), «Notationes Legentis: The Title сυсτάτηс», BASP 29, 127-129.

Lewis, N. (1997), The Compulsory Public Services of Roman Egypt (Pap. Flor. 28; 2nd ed., Firenze).

Palme, B. (1998), «Praesides und Correctores der Augustamnica», Antiquité Tardive 6, 123-135.

Perpillou-Thomas, F. (1995), «Artistes et athlètes dans les papyrus grecs d’Egypte», ZPE 108, 225-251.

Reiter, F. (2002), «P.Vind. Sal. 14 und die Kopfsteuerrate im Herakleopolites», ZPE 138, 129-132.

Remijsen, S. (2011), «The So-Called “Crown-Games”: Terminology and Historical Context of the Ancient Categories for Agones», ZPE 177, 97-109.

Schmitz, H.D. (1970), Tὸ ἔξθoc und verwandte Begriffe in den Papyri (Diss. Köln).

Searchable Greek Inscriptions (January 2011): <http://epigraphy.packhum.org/inscriptions>.

____________

1 I thank Hermann Harrauer for allowing me to publish this text, and Bernard Palme for reconfirming this and for providing me with a digital photo of the papyrus with its publication right. I also thank Rodney Ast for correcting my English, and the anonymous referee for his comments and suggestions.

2 For a bibliography on petitions, see P.Dub. 18; see also Feissel/Gascou (2004). A list of early Byzantine petitions (284 – end 4th century AD) is found in Kramer (1987) 155-161.

3 Records suggest that the papyrus was bought in 1893 and found at Soknopaiou Nesos. The latter is, however, hardly possible since no papyri are known to have come from Soknopaiou Nesos after the middle of the third century AD; see Hoogendijk/Worp (2001) 58. SB XXVI 16727 (first quarter of IV AD) published there offers a comparable case of a Vienna papyrus (inv. G 24704), bought in 1893 and ascribed to Soknopaiou Nesos, but rather found in Bousiris (Delta). According to H. Loebenstein in P.Rainer Cent. (p. 21), the Vienna papyri from Soknopaiou Nesos had been given the inventory numbers G 24800-25024, so that the aforementioned text G 24704 and the present G 24715 indeed fall outside this group.

4 Carrez-Maratray (1999) 166-192.

5 Palme (1998) 129.

6 Clarysse (2003), attestations p. 357, n. 41-42 with updated list at: <http://www.trismegistos.org/arch/index. php> (January 2011).

7 See Frisch (1986); Drew-Bear (1988). A list of athletes in Perpillou-Thomas (1995) 241-251; none of the 131 athletes in the list comes from Herakleopolis.

8 For athletes’ exemption of liturgies, see Lewis (1997) 90.

9 Even former athletes sometimes held official functions in their city as a second career; see Drew-Bear (1988) 233.

10 An early fourth-century attestation of games can be found in P.Oxy. LXIII 4357 (later than 27 Oct., AD 317).

11 Tentatively read as: 1]. 2]ν 3]υ 4]. 5]. 6]α 7 π]α̣λαιουc̣ 8].ουρα 9]сαρ. 10]… 11]… 12]..α̣ρ̣ο̣υ̣ 13].ω. 14]υμων̣ 15].λο 16]λα.

12 Hendriks (1980); Hendriks (1984); Harrauer (2010) 19.

13 See below 3, n.

14 See Harrauer (2010), Abb. 184 (AD 339); 188 (AD 343); 192 (AD 356); and, more cursive, Abb. 191 (AD 348).