New texts from the Al-Hayz Oasis

A preliminary report

Prologue

In the spring of 2003, a Czech multidisciplinary team began archaeological field exploration in the southern-most part of the Bahriyah Oasis in the Egypt’s Western Desert. Since then, six expeditions to the same area have taken place, focusing on various aspects of both prehistorical and historical human presence and activities in this now-barren land.

Inter alia, several Late Roman Period sites were recognized and mapped through analyzing satellite images and surface prospecting during the initial phase of the research. After some trial digs at different sites, it was decided to start excavations at one site, called Bir Showish by local people. In November 2005, prospect trenches and shafts were dug, proving the Late Roman dating of the site and demonstrating its rural settlement character.

In 2005, the first ostraca were found; my text presents new textual evidence made available through this exploration. A few facts about the site and the exploration itself must first be stated2.

Bir Showish

The modern-day site of Bir Showish is located in al-Hayz or the southern part of what in late Antiquity used to be called the Small Oasis – Mikra Oasis or Oasis Parva in Greek and Latin, respectively. Other names were applied to the Oasis in the past, and its modern name is Bahriyah («the northern one» in Arabic)3. Although about 40 km of desert separate al-Hayz from the northern part of the Oasis, and though this rural area can be considered to form a separate oasis, administratively it belongs to the Bahriyah Oasis, as it most probably did in Antiquity, too. The Black Desert region of the al-Hayz Oasis is wellknown for its colors and pyramid-shaped hills, its landscape formed by the erosion of iron sandstone and Nubian sandstone.

The archaeological exploration by the Czech team at Bir Showish focused on detecting functionally different areas of the site. Besides houses, workshops, fields and cemeteries were recognized. Also documented was the underground aqueduct system or qanawat (or manawar) network, where the ventilation shafts are typically marked by the mounds of material dug out from the subterranean channels and/or by vegetation mounds. Two twin kilns inside the settlement and a rock tomb in a hill east of the village were excavated and documented at this time.

The settlement occupies about 20 hectares. Several houses – presumably individually located farmsteads – are still clearly visible on the surface, with what might be considered orchards and gardens in between. These are mostly two-story buildings, large mud-brick structures with unusual rock facing in their lower parts. The ground plan of House No. 2, located in the center of the village, was documented to measure 23 x 19 m4. The layout of the rooms and inner structure of House No. 4, located in the northern part of the settlement, were also recorded. House No. 1 was not measured at all.

Most of the ostraca come from House No. 3, where the ground plan was measured to be 37 x 23 m, or about 850 m2, which should be doubled or even tripled to take into consideration upper floors and the rooftop. This house consists of 33 documented rooms belonging to two distinctive sections, with rooms arranged around an open space or a yard. The entrance of the house faces west, although its orientation is not exact. The house was partially excavated in 2005, and then during the 2007 season5.

As implied, excavations of this settlement were rather limited – generally, only upper layers of sand were removed to uncover the crowns of walls and to obtain datable pottery samples. In House No. 3, however, the upper floor was uncovered in a good number of rooms. Room 11 then – where a number of ostraca were found – was excavated down to the lower-floor level.

On the basis of pottery, it was possible to date the site to the second through fifth, or even early sixth century, which, as I shall demonstrate, correlates closely with the ostraca6. The settlement seems to have been abandoned by the end of the fifth century – at least, we do not have material remains securely datable later than the early fifth century7. This date is also confirmed in numismatic material, since the latest mintings identified so far are those of Theodosius I. (379-395) and Valentinianus II. to Honorius (375-423)8. The ancient name of the village is not attested in any of the ostraca thus far studied.

Ostraca Bir Showish

The set of ostraca obtained through excavations at Bir Showish consists of 64 individual fragments belonging probably to 50 pieces of ostraca. Except for the two pieces from House No. 4, all the ostraca come from House No. 3, forming thus a closely related corpus. The vast majority of the ostraca was found in a single room, room 11, originally considered to be two rooms (once labelled rooms 11 and 12)9. Unfortunately, only about 40 % of the ostraca are complete or only slightly damaged; many of them are very difficult to read due to their poor state of preservation.

As for dating, indictions usually appear, attributing single ostraca to the years of the fifteen-year tax cycle. Occasionally the months were noted, whereas only two exact years have been identified so far, namely 79 and 80. The first (inv. 30/BS/05), supplemented by «Mesore 11», gives August 4th, 403, while the second one (inv. 32/BS/07) stands alone allowing us to date it to 403/404. Dating according to years most probably follows the era of Oxyrhynchos, which is also the case with ostraca found earlier in the same oasis by Fakhry and published in 1987 by Wagner10.

Until now, all the ostraca discovered at this site are in Greek. They are documentary in their content, reflecting daily-life negotiations in their economic, administrative and social context. Not surprisingly, they tend to be very formulaic, most of them being receipts for delivery of various agricultural articles. What follows is a preliminary edition of two pieces.

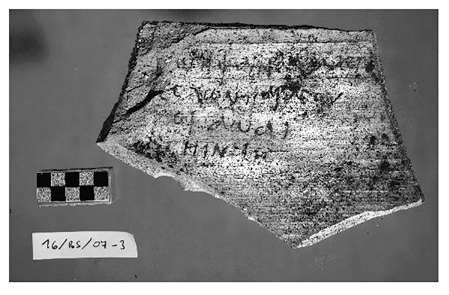

Inv. 16/BS/07-3; 11,3 x 7,7 cm; Bir Showish, House No. 3, room 12, cont. 1 (60-80 cm)

[’I]ω̣cὴφ Ἀβραὰμ χέρ(ειν).

ἔcχων παρὰ coῦ

ὄρ(νεον) α ᾠὰ ι

η ἰνδικ(τίονοc).

Joseph to Abraham, greetings. I received from you 1 chicken and 10 eggs, (the year of the) 8th indiction.

1 l. χαίρ(ειν) 2. l. ἔcχον 3 also possible is ὀρ(νίθιον), ϊ

Fig. 1: Greek ostracon inv. 16/BS/07-3; Bir Showish, House No. 3. By courtesy of M. Frouz.

3. There are more attestations for payments in chickens and eggs both within the texts from the Bir Showish ostraca (e.g. 32/BS/07) and from the Bahriyah Oasis in general (O. Bahria 2, O. Sarm. 7, O. Sarm. 10, O. Sarm. 11, O. Bahria div. 4). Whereas both ὄρ(νεον) and ὀρ(νίθιον) can be resolved in line 3, the full form is not attested on any of the Bir Showish ostraca so far; also all other examples from the Bahariya Oasis are in the form ὄρ(), always resolved by Wagner as ὄρ(νεον).

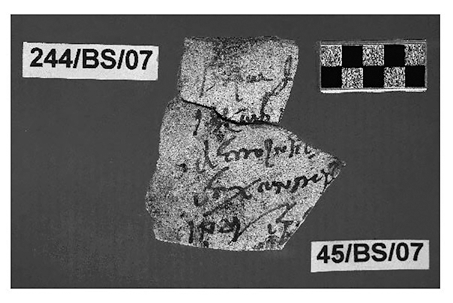

Inv. 244/BS/07; 2,7 x 2,1 cm; Bir Showish, House No. 3, room 11 (W.), cont. 05

Inv. 45/BS/07; 5 x 4 cm; Bir Showish, House No. 3, room 12, cont. 02 (140 cm)

Ἱλάρῳ Ἀ[βραὰμ]

Ἰακῶβ γ̣[εωργῷ]

δεcπoίνηc χ̣[αίρειν.]

ἔcχων παρ[ὰ cοῦ (ὑπὲρ)…]

ἰνδι(κτίονοc) ἐρε̣[οξύλου

[.]ι̣[…]α̣[

. . . . .

Hilaros to Abraham son of Jacob, farmer of a mistress (or landlady), greetings. I received from you (…) of cotton (?) (for the year of the) (…) indiction.

1 l. Ἵλαρoc 2-3 reading supported by ostracon inv. 43/BS/07, where the reading of γεωργῷ δεcπoίνηc is clear 4l. ἔοχον 5 also possible is ἔρειου (ἔριου, «wool»)

Fig. 2: Ostraca inv. 244/BS/07 and 45/BS/07; Bir Showish, House No. 3. By courtesy of M. Frouz.

3. Mentions in papyrological evidence of δέcποινα (landowning woman) are quite rare. Here the lacuna at the end of the line 2 theoretically could contain οἰκο- but the parallel phrase in 43/BS/07 makes it very improbable.

4. At the end of the line an indiction number is expected.

5. Within the Bir Showish ostraca, cotton is mentioned also in 94/BS/07.

Abraham son of Jacob, who most probably appears on both of the ostraca cited here, was apparently a tenant farmer renting a farm from a female landlord whose name is not given anywhere in the ostraca. There are more receipts addressed to Abraham in the corpus; one gets the impression that we are reading his archive of documentary texts or business papers.

Besides this Abraham, there is one other farmer addressee of several receipts. His name is Apollon, and among other material culture retrieved from House 3, there are two oil lamps inscribed with his name11. Both the ostraca addressed to Abraham and to Apollon were found in the same stratigraphic layers of House 3, some of them in niches in the wall. Until now, however, nothing specific about a possible relationship between the two groups could be learnt; and it has proven difficult to date these examples. One of the Abraham ostraca can be dated to 403/404 (inv. 32/BS/07). Unfortunately, none of the Apollon ostraca is dated by an exact year. Adding further complication, indiction dates appearing in the Abraham ostraca both precede and follow those noted in the ostraca addressed to Apollon. Thus the question of dating the indiction cycles in the two groups of ostraca remains to be addressed.

Some observations on local agriculture and administration

A comprehensive study of the local agriculture and administration as mirrored in the Bir Showish ostraca certainly needs to be the object of careful and complex examination. For now, however, we can present a few preliminary remarks and observations.

Agriculture as practiced in the Oasis even today can be described as follows: dependence on irrigation (made possible by water wells); no mass production of cereals (because of the limited amount of tillable land); and predominance of fruit crops and vegetables. Even today, one can observe that in al-Hayz cultivated land is characterised by gardens and orchards rather than by fields. It is not surprising, therefore, that we find mentions in ostraca of lentils (φακοί), olives (ἐλαία), a chicken (ὄρνεον), an egg (ᾠόν), wool (ἔριον), cheese (τυρίον) and chaff (ἄχυρον)12. The first mention of cotton (ἐρεόξυλον) in textual material securely associated with the Small Oasis is noteworthy13. Surprising, however, is the lack of any reference to dates, a product so typical of the Bahriyah Oasis even today.

Of various occupations, offices and officers attested in the ostraca texts, farmer (γεωργόc) is the most common, followed by priest (πρεcβύτεροc). Also mentioned is agrophylax (ἀγροφύλαξ) whose duty was probably to guard artificially irrigated land14. Two mentions of πάγαρχοc (inv. 44/BS/07 and 272/BS/07-1 to 3) are of special interest, since this is an office considered to have been created toward the end of the fifth or the beginning of the sixth century15. The name of this pagarch (Ἰcάκ) appears to be the same as an officer attested in an ostracon discovered in Bahriyah earlier by Fakhry (O. Dor. 5,1) and notable as the hitherto earliest attestation of πάγαρχοc, though we should note this latter inscription is fragmentary16.

Christianity

One cannot overlook another question raised by the ostraca about the religious identity of the Bir Showish villagers. At least some of the persons featuring in these texts appear to be Christians. Most eloquently it can be noticed in their «Christian names»: if we assume a general absence of Jews in the region in this period, the following biblical names would identify the villagers as Christians. Besides Joseph, Abraham and Jacob already mentioned, there are also mentions of Isaac and Timothy. Specifically Christian identity is also reflected in attributing the term πρεcβύτεροc to a man called Theon (inv. 16/BS/07-21). Lastly, we have the rare indication of Christianity in the material record: a bowl (inv. 34/BS/07) with the explicitly Christian motif of a red-painted cross inside it, was excavated in House No. 3.

Epilogue

The ostraca introduced with this short paper are housed in the SCA Museum in al-Bawiti, the center of the Bahriyah Oasis. As should be apparent from these remarks, there is much work to be done on the material. Editing and publishing the Bir Showish ostraca is part of my doctoral dissertation project. Contextualizing archaeological data would be necessary to provide a complex interpretation of the corpus of ostraca.

I conclude by mentioning that although no papyri have been excavated at al-Hayz, inscribed pottery found there might provide further textual evidence of activities at the site. This evidence, however, would be a subject for another paper.

Bibliography

Bagnall, R.S. (1997), The Kellis Agricultural Account Book (Oxford).

Bagnall, R.S. (2008), «SB 6.9025, Cotton, and the Economy of the Small Oasis», BASP 45, 21-30.

Bárta, M. et al. (2009), Ostrovy zapomněni: El-Héz a české výzkumy v egyptské Západní poušti (Praha).

Bonneau, D. (1988), «Agrophylax, le “garde des champs”», in Proceedings of the XVIIIth International Congress of Papyrology, Athens 1986 (Athens) II 303-315.

Drecoll, C. (1997), Die Liturgien im römischen Kaiserreich des 3. und 4. Jh. n. Chr.: Untersuchung über Zugang, Inhalt und wirtschaftliche Bedeutung der öffentlichen Zwangsdienste in Ägypten und anderen Provinzen (Stuttgart).

Fakhry, A. (1950), Bahria Oasis II (Cairo).

Falivene, M.R. (2009), «Geography and Administration in Egypt (332 BCE – 642 CE)», in Bagnall, R.S. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology (Oxford/New York) 521-540.

Mazza, R. (1995), «Ricerche sul pagarca nell’Egitto tardoantico e bizantino», Aegyptus 75, 169-242.

Musil, J./Tomášek, M. (2009), «Archeologický výzkum pozdně římského osídlení na lokalitě Bír Šovíš», in Bárta, M. et al., Ostrovy zapomnění: El-Héz a české výzkumy v egyptské Západní poušti (Praha) 217-248.

Wagner, G. (1987), Les Oasis d’Egypte à l’époque grecque, romaine et byzantine d’après les documents grecs (Le Caire).

____________

1 My acknowledgements go to my dissertation advisor Miroslav Bárta who is currently the director of the Czech mission in al-Hayz, and to Roger Bagnall who introduced me to the world of papyrology as a visiting graduate student at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. I also thank Elizabeth Williams for thoroughly reviewing the English version of this paper. My stay at ISAW was made possible through the Fulbright Fellowship program; the research has also been supported by the Charles University Grant Agency grant GA UK 22209.

2 So far, the archaeological part of the exploration was only treated in a more general book in Czech – Bárta et al. (2009); forthcoming is a scholarly publication in English. (Palaeo) botanical survey can be followed online at <http://westerndesertflora.geolab.cz>.

3 Also the Seven Nomes Oasis, Oasis of Oxyrhynchos (or Pemdje or even Bahnasa), or simply (the) Oasis (chiefly in the texts from Oxyrhynchos); see Wagner (1987) 134-137.

4 Musil/Tomášek (2009) 229.

5 Basic archaeological data on House No. 3 can be found in Bárta et al. (2009) 234-247.

6 Musil/Tomášek (2009) 233.

7 Musil/Tomášek (2009) 231.

8 These are AE maiorina (inv. 114/BS/07) and AE IV (208/BS/07); based on an unpublished expert’s opinion by Jiří Militký.

9 This is the only room to have been excavated completely.

10 Greek and Coptic ostraca – together with one written in Syriac – were found near the temple of Alexander and at al-Me’ysera. The Greek ones (O.Bahria, O.Sarm., O.Dor., O.Bahria div.) were published in Wagner (1987) 86–109 ; the Coptic ones remain unpublished. For the original account, see Fakhry (1950) 47 and 92–94.

11 The first one reads ΑΠΟΛ BB (68/BS/07), the other one reads AΠOΛΛΠωC BB (225/BS/07), where the double beta remains an enigma.

12 Wool (ἔριον) possibly in 45/BS/07; where, however, cotton is more probable reading (see above).

13 Inv. 45/BS/07 and 94/BS/07. See Bagnall (2008), where an interpretation is offered of a papyrus found probably in Oxyrhynchos (P. Mich. 1648 = SB VI 9025) that supposedly refers to the Small Oasis as the place the cotton mentioned in it was to be delivered for a lady called Areskousa to make new garments. So far, no (palaeo) botanical evidence from al-Hayz is available for cotton. Macro-analysis of three samples from Bir Showish did not reveal any traces of cotton. This is not surprising, since all the samples came from kitchen waste, where cotton can hardly be expected – the Oasites had a better source of oil, namely olives (Petr Pokorný, personal communication). In any case, Gossypium arboreum was noted in the past century as growing wild in Bahriyah (after Bagnall [1997] 40).

14 Thus Bonneau (1988) after examining evidence for this liturgical official; see also Drecoll (1997) 170.

15 Mazza (1995) 225. The term παγαρχία, however, appears first in the fourth century; see Mazza (1995) 172; see also Falivene (2009) 535, who misleadingly states that «the pagarch first appears in our sources toward the end of the fifth century».

16 O. Dor. 5, dated to either 407/408 or 422/423, was published by Wagner (1987) 103, and is referred to by Mazza (1995) 174. Although it is a pagarch who is the writer of the both ostraca, only kappa remains from the (assumed) name in O. Dor. 5, 1, not allowing us to satisfactorily compare the scribal hands.