Following in father’s footsteps

The question of father-son scribal training in eigth century thebes

Introduction

The published material concerning the village Jeme comprises approximately 150 papyrus and several hundred ostraca texts, dated to the 7th and 8th centuries AD1. It is the documentary texts on papyrus that provide the primary evidence for the following discussion. These documents were written in a variety of styles. This is most clear visually, with the range of handwritings found: from square uncials, to round bilinear hands with elaborate flourishes, to heavily cursive hands2. This palaeographic range is reflected in the variation found in the formulary and orthography employed by the various scribes. Collectively, this indicates that there were different schools of scribal training in the area. The issue at hand, here, is how these scribes were trained and what evidence there is for this.

Before determining whether different schools existed in which villagers could learn the scribal profession (here, specifically, training in the composition of documentary texts), there is an issue of terminology that has to be addressed. The use of the term «school» itself is problematic3. What is meant by «school», and can a physical environment be thought of, or is this even necessarily signified by the term? There are sites in Thebes that served as physical locations for primary education, in particular the monastery of Epiphanius and that at Deir el-Bakhit4. But what evidence is there in the village itself? Not only is there a lack of extensive archaeological data, it might be the case that «schools» left no discernable record5. For example, pupils may have been taught in a single room in a building or out in the open, whether in a courtyard or an area outside the village proper. The only evidence on the way scribes were taught is the documents themselves: complete texts mostly written by highly accomplished writers. Rather than search for «schools», an alternative approach is to look for teachers6; specifically, to try to identify the influence of older scribes upon younger ones and to determine what evidence exists to allow such an analysis.

Many of the Jeme papyri are signed, allowing the careers of individual scribes to be traced and connections between them to be made7. Onomastic evidence strongly suggests the existence of father-son groupings:

| Father | Son |

| Psate son of Pisrael | David son of Psate |

| Johannes son of Lazarus8 | Aristophanes son of Johannes Joannake son of Johannes |

| Shmentsnêy9 son of Shenoute | Shenoute son of Shmentsnêy |

For earlier periods, Cribiore has shown the influence of parents, especially fathers, in the education of their children, noting the vested interest that they held in such matters: children were considered a projection of their parents’ ambitions, a support for their old age, and a continuation of the family’s line10. On onomastic grounds, it appears that sons followed their fathers’ profession, but this does not automatically signify that fathers were responsible for training them.

In order to assess whether or not this was the case, it is necessary to examine the documents they produced, working on the hypothesis that, if fathers did train their sons, there will be distinct and consistent similarities in texts produced by both generations. The father-son pairing selected for analysis here is Shmentsnêy and Shenoute. On practical grounds, their combined dossier is the smallest of the three pairings listed above11:

| Shmentsnêy son of Shenoute |

P.KRU 12: sale between Patermoute son of Constantine and Aaron son of Shenoute12 P.KRU 13: sale between Kyriakos son Demetrios and Aaron son of Shenoute P.KRU 106: testament of Anna daughter of Johannes |

| Shenoute son of Shmentsnêy |

P.KRU 1: sale between Psate son of Philotheos and Aaron son of Shenoute P.KRU 2: sale between Tagape and Esther, daughters of Solomon, and Aaron son of Shenoute P.KRU 4: sale between Talia daughter of Pacham and Aaron son of Shenoute P.KRU 54: bequest from the estate of Tsauros daughter of Takoum. |

In addition, I have checked the originals of each manuscript, except P.KRU 106. Moreover, these two scribes are connected beyond their name. Both have ecclesiastic titles: Shmentsnêy states that he was priest (πρεcβύτεροc) and governor (ἡγεμών) of the Holy Church of Jeme, Shenoute simply that he was priest and deacon (διάκονοc), but does not specify of which church (see examples 5 and 6)13. Both men were priests as well as scribes. Both men also wrote the same type of documents, predominantly sales, for the local villagers, and mostly for the same villager: Aaron son of Shenoute (P.KRU 1, 4, 5, 12 and 13).

As they have the same two names, onomastic evidence does not clarify which scribe is the elder. Further, none of these texts are absolutely dated. On the basis of other criteria, primarily prosopographic connections between texts, Shmentsnêy’s texts date primarily to the mid-730s and Shenoute’s from 748 to 76314. Shmentsnêy’s dates are approximately 1015 years before those of Shenoute, thereby making him the elder and thus the father.

The criteria upon which the comparison of the documents is made are their palaeography, formulary, and orthography. The following observations are based on a preliminary and not an exhaustive study of the work of both men. As such, the observations presented here and the resulting conclusions will be refined through future research.

Palaeography

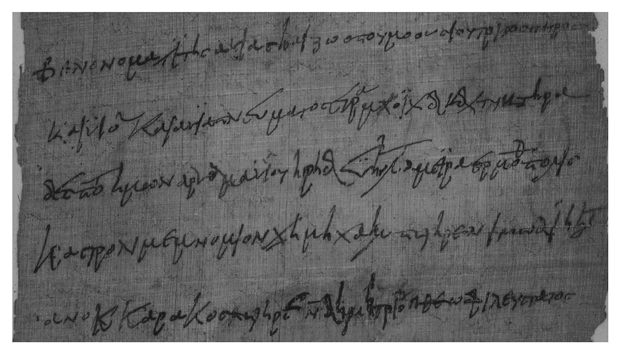

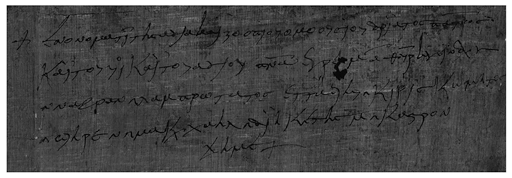

Figures 1 and 2 show sections of the beginning of texts by each scribe. As they are intended to be illustrative of the overall appearance of each one’s writing, they are not reproduced to scale.

Figure 1: Shmentsnêy (P.KRU 13, 1-5) © The British Library Board (Or. 5985)

Figure 2: Shenoute (P.KRU 4, 1-5) © The British Library Board (Or. 4870)

The overall appearance of Shmentsnêy and Shenoute’s hands is different. Shenoute’s is more free flowing, more rounded; letters are wider and the horizontal spacing is greater. His descending strokes sweep down to the left and end in finials that flow in the same direction. Shmentsnêy, on the other hand, is more measured in this respect; his descenders are straight and tick to the right, against the direction of his writing.

Comparison of parallel phrases shows how individual letter formations differ between the two. In the short extracts provided in figures 1 and 2, a number of differences are apparent.

| Letter | Shmentsnêy | Shenoute |

| Initial epsilon | Small, compact, round. This is in contrast to its writing later in the document (see here lines 2 and 3) where he uses the larger form. | Large with an extended upper limb. This form is rarely found in the main body of his documents. |

| iota with diaeresis | Two distinct dots are written. | The two dots are curved strokes, often written in one motion without lifting the pen, creating the appearance of a circumflex rather than a diaeresis. |

| nu | Three strokes, angular. | One or two motions, curved. |

| upsilon | In lines 1-4 (except once in line 1), it is written without a vertical stem. It is written with diaeresis in lines 2 and 3. | Always written with a stem and never with diaeresis. |

The differences in the writing of upsilon at the beginning of the document, the Greek protocol, are indicative of a wider practice found at Jeme. Certain scribes, when writing formulae entirely in Greek, mark this use of language by a change in their writing. Shmentsnêy follows the same practice, but Shenoute does not15.

If this analysis is extended to include the rest of the documents, beyond the small sections shown in figures 1 and 2, a number of other key features are found. These include the writing of the sigma-tau ligature by both. Shmentsnêy writes these as two distinct letters, but Shenoute writes them as a composite stigma-form ligature (ϛ) in which the component parts of each letter are divided and realigned. Apart from the Greek invocation at the beginning of the document, where he writes a cursive form of eta, Shmentsnêy writes a square majuscule letter. This form was not written by Shenoute.

A comparison of P.KRU 13 and 54, by the respective scribes, shows a striking difference in line spacing, which can be quantified. The first sheet of P.KRU 13, following the modern cut, contains 19 lines, as does the main text of P.KRU 54 (the remaining lines comprise a witness statement in a second hand, then Shenoute’s signature). Shmentsnêy writes his 19 lines in 35 cm, but Shenoute squeezes his into only 22 cm. This is not connected to the size of their letters, which are the same height. It also does not appear to be connected to the amount of space available on the sheet. Although P.KRU 54 is a secondary use of the papyrus (it is written on the verso of P.KRU 26), Shenoute did not start writing at the top, but one-quarter of the length down. This indicates that Shenoute had a tendency towards cramped writing that was not shared by Shmentsnêy, but this needs to be thoroughly checked across all the documents.

Overall, the palaeographic differences between these two far outweigh any similarities that may be identified.

Formulary

Shenoute’s use of formulary is consistent throughout his three sale documents. P.KRU 54 is not a sale document, but the acknowledgment of a bequest to a local church, and is shorter than the three deeds of sale. As such, it does not include many of the same set clauses. In particular, expressions of consent on the part of the deceased party (Tsauros daughter of Takoum), who is represented by a third party (Komes son of Damianos), are omitted.

Shenoute and Shmentsnêy wrote almost identical formulae for the invocation of the Holy Trinity, date, introduction of the two parties, and the provision of a writing assistant and witnesses. These are the most standard formulae used by all scribes in the village. Beyond this, Shmentsnêy is less consistent than the younger scribe. He does not seem to follow a single set form so much as adapt basic component parts to new structures and orders. The long donation text, P.KRU 106, in particular shows a great degree of variation. As most of the formulae of these documents are long, just three of the shorter ones – the free-will clause, the oath, and the scribe’s own notation – are discussed below.

1) Shmentsnêy’s free-will clause

(a) пᴧɩ ɴтᴧɴтɩ пєɴoʏoєɩ єpoq єɩoʏɷϣ ᴧʏɷ єɩпєɩɵє xɷpɩc ᴧᴧᴧʏ ɴĸpoʏq zɩzoтє zɩxɴσοɴc zɩᴧпᴧтн zɩcᴧɴᴧpпᴧгн zɩпєpɩгpᴧϕн ᴧᴧᴧᴧ zɴтᴧпpozʏpєɩcɩc ɴмɩɴ ɴмoɩ «This which we have agreed to, and I desire and trust without any guile, fear, violence, deceit, artifice, ruse, but through my own free choice.» (P.KRU 12, 15-18)

(b) xɷpɩc ᴧᴧᴧʏ ɴĸpoq zɩzoтє zɩzoтє zɩxɴσοɴc zɩᴧᴨᴧᴛᴧ zɩᴧᴧᴧʏ ɴcєɴᴧpпᴧгє ᴧʏɷ пᴧpᴧгpᴧϕн мɴᴧᴧᴧʏ ɴᴧɴᴧггн ĸн ɴᴧɩ zpᴧɩ «without any guile, fear, violence, deceit, any artifice and ruse, and any constraint set against me» (P.KRU 13, 63-66)

(c) єємɴᴧᴧᴧʏ ɴᴧɴᴧгĸн ĸн єzpᴧɩ єpoɩ oʏᴧє λᴧᴧʏ ɴĸpoq zɩzoтє oʏᴧє xɩɴσoɴc zɩᴧпᴧтн zɩcʏɴᴧpпᴧгн zɩєпɩpɩгpᴧϕн ɴɩм ᴧᴧᴧᴧ єzɴᴧɩ zɴoʏɷϣ ɴᴧтpzтнq мɴoʏᴧoгɩcмoc ɴᴧтϣɩʙє ᴧxɴzнт cɴᴧʏ мɴoʏcʏɴнтєcɩc ємɴĸpoq ɴzнтc мɴoʏzнт єqcoʏтɷɴ мɴoʏпɩcтɩc єcтᴧxpнʏ єcxннĸ єʙoλ ммɴтxoєɩc ɴɩм ɴᴧɩĸᴧɩoɴ xɷpɩc ʙɩᴧ xɷpɩc ᴧпᴧтн xɷpɩc cʏɴᴧpпᴧгн xɷpɩc єᴨoɩpoɩᴧ єʙoᴧ zɴσʏɴᴧʏɴoc ɴɩм «As there is no constraint set against me, nor any guile, fear, nor violence, deceit, artifice, and any ruse, but through unrepentant desire, unchanging reasoning, without two minds, with guileless conscience, a certain mind, firm and complete belief, and all just authority, without force, without deceit, without artifice, without influence from any danger.» (P.KRU 106, 23-31)

2) Shenoute’s free-will clause

єɩoʏɷϣє ᴧʏɷ єɩпɩɵє xɷpɩc ᴧᴧᴧʏ ɴĸpoq zɩzoтє zɩxɩɴσoɴєc zɩᴧпᴧтн zɩcʏɴ ᴧpпᴧгн zɩєпɩгpᴧϕн ємɴᴧᴧᴧʏ ɴᴧɴᴧгĸн ĸн ɴᴧɴ єzpᴧɩ ᴧᴧᴧᴧ мпᴧcʏ ᴧгᴧɵн ĸᴧɩ ĸᴧᴧн пpoєpᴧɩcᴧɩ «I desire and trust without any guile, fear, violence, deceit, artifice, ruse, and any constraint set against me, but in all good and proper free choice.» (P.KRU 4, 19-23; see also 1, 30-37 and 2, 11-14)

Apart from the addition of an introductory phrase in P.KRU 1, ᴧɪ† пᴧoʏoɩ єpoc «I have agreed to it», Shenoute’s writes the same free-will clause throughout (example 2). P.KRU 12 and 13 by Shmentsnêy (examples 1a and b) are based on the same core feature as that of Shenoute’s, that is, the tautological string of possible constraints. However, neither is identical and they are integrated into the framework of the documents in different ways. Of these, 1b is the simplest, which is expanded in 1a by an introduction and final element, making it the most similar to Shenoute’s P.KRU 1. P.KRU 106 is almost completely different (example 1c). The order of the component parts has been inverted and an extended tautological string added at the end. This string is unparalleled in the Jeme corpus, and only P.KRU 14, 20-26 by Aristophanes son of Johannes provides a close comparison (in length rather than content, as little vocabulary is shared between the two)16.

Structurally, in P.KRU 13 the clause appears in an unusual place. The free-will clause normally appears in the opening section of the document, before the recording of the matter at hand. Here, it instead appears at the end of the document, in the final clause noting the execution of the document and its validity17.

In order to further affirm that they are acting of their own volition, and that everything included in the document is correct, the first party swears an oath.

3) Shmentsnêy’s Oath Formula

єɩɷpĸ ɴпɴoʏтє пᴧɴтɷĸpᴧтɷp мɴпoʏxᴧɩ ɴɴxɩcooʏє єтᴧpxн xɷɴ «I swear by God Almighty and the health of the Lords who rule over us.» (P.KRU 12, 18-19)

4) Shenoute’s Oath Formula

єɴɷpєĸ ᴧє мɴɴcoc ɴтєᴧpɩᴧc єтoʏᴧᴧʙ ɴzoмooʏcɩoɴ пєɩɷт мɴпɷнpє мɴпєᴨ̄ɴ̄ᴧ̄ єтoʏᴧᴧʙ мɴпoʏxᴧɩ ɴɴєɴxɩcooʏє ɴєppooʏ ɴᴧɩ єтᴧpxєɩ єxoɴ єʙoᴧ zɩтɴпoʏєzcᴧzɴє мᴨɴoʏтє мпᴧɴтɷĸpᴧтɷp «I swear by the holy consubstantial Trinity, the Father, Son and the Holy Spirit, and the health of our royal Lords who rule over us now, through the command of God Almighty.» (P.KRU 1, 37-44, 2, 14-17 and 4, 23-27)

There is an omission of the final element, zɩтɴпoʏєzcᴧzɴє мпɴoʏтє ппᴧɴтɷĸpᴧтɷp, in P.KRU 2, but otherwise all three instances by Shenoute are the same. The oaths written by both men are dedicated to divine and secular authorities, but the same formula is not employed to do so. Shmentsnêy’s formula is shorter and this is largely because it is addressed to God Almighty alone and not the Holy Trinity.

Shenoute includes the oath in each of his sale deeds, and the oath is a standard component of both sales and donations18. Its omission from P.KRU 54 is expected, for the reasons stated at the beginning of this section. The same omission in P.KRU 13 and 106, a sale and donation respectively, is therefore unusual. The reason for this can surely be attributed to Shmentsnêy’s more fluid inclusion, or lack thereof, and adaptation of standard features.

At the end of the document, the scribe writes a notation stating that he is responsible for having written it. In the following examples, the abbreviations used for Greek words are not expanded, in order to most accurately represent what the scribes wrote.

5) Shmentsnêy’s notation

(a) ᴧɴoĸ+ xмтcɴнʏ+ ᴨєɩᴧx/ɴпpє/є/ᴧʏɷ+ пzʏгм пϣнpє ɴcєɴɵ ɴтєĸĸᴧнcɩᴧ єтoʏᴧᴧʙ ɴϫнмн+ ᴧɩczᴧɩтc ɴтᴧϭɩϫ «I, Shmentsnêy, the most humble priest and hegemon, the son of Shenoute, of the Holy Church of Jeme, have written it by my hand.» (P.KRU 12, 67-70)

(b) ᴧɴoĸ xмтcɴнʏ пєɩᴧx пpєpє ᴧʏɷ пzʏгм пϣнpє ɴcєɴɵ ᴧɩczᴧɩ ɴтᴧϭɩϫ «I, Shmentsnêy, the most humble priest and hegemon, the son of Shenoute have written by my hand.» (P.KRU 13, 84-85)

(c) ᴧɴoĸ xємɴтcɴнʏ пєɩєᴧᴧx/мпpєcʙ/ᴧʏɷ пzʏгoʏмєɴoc пϣнpє ɴϣєɴoʏтє ɴтєĸĸᴧнcɩᴧ єтoʏᴧᴧʙ ɴϫнмє ᴧɩczᴧɩ пєɩᴧɷpɩᴧcтɩĸoɴ cʏɴтpᴧϕн ɴтᴧϭɩϫ «I, Shmentsnêy, the most humble priest and hegemon, the son of Shenoute, of the Holy Church of Jeme, have written this written donation by my hand.» (P.KRU 106, 242-245)

6) Shenoute’s notation

єгo cєɴoʏɵ ʏɩo мᴧĸ/xмтcɴнʏ єᴧᴧx пpє/є/ᴧпo ĸᴧcтpoʏ мємɴoɴɩoʏ єгpᴧψᴧc19 «I, Shenoute son of the late Shmentsnêy, the most humble priest from castrum Memnonion, wrote it.» (P.KRU 4, 94-95; see also 2, 60-61 and 54, 24)

Shenoute writes his notation in Greek, including the use of the Greek name for Jeme, Memnomion (Μεμνόνιον). Shmentsnêy writes his in Coptic. This is odd, as it makes him only one of two scribes at Jeme to write the protocol at the beginning, i.e. єɴ oɴoмᴧтɪ…, in one language (Greek) and his signature at the end in another (Coptic)20. This, together with the variation in abbreviation style across his documents and the inclusion of unusual vocabulary in 5c (cυγγραφή), again shows Shmentsnêy’s disinclination to adhere to standard patterns.

Orthography

Not including miscellaneous spelling errors, of words otherwise written correctly or of Greek words, Shmentsnêy and Shenoute each exhibit orthographic peculiarities not shared by the other. Shmentsnêy frequently writes the pronominal direct object marker with unassimilated initial nu: ɴмo⸗, not мɴo⸗ (underlined in examples 7 and 8).

7) ᴧᴧᴧᴧ zɴтᴧпpozʏpєɩcɩc ɴмɴɩ ɴмoɩ «rather, through my own free-will» (P.KRU 12, 18; in this example, unassimilated nu is also found with ɴмɩɴ for ммɩɴ)

8) ᴧʏɷ ɴᴧтпᴧpᴧcєᴧєʏє ɴмoc єʙoᴧ zɩтoтoʏ ɴɴмoc «and unimpeachable through the laws»(P.KRU 13, 12-13)

This feature is mostly overlooked for Theban texts in Kahle’s study of dialectical variation in non-literary texts. Kahle cites only P.KRU 3, 64: тɩcтнxє ᴧтɩпpᴧcɩc пpoc ɵн тccнz ɴмoc; he notes, however, that more thorough examination of Theban corpora might reveal additional examples21. A more common Theban feature is his practice of replacing epsilon with alpha in prepositions and adverbs (underlined in examples 9-12)22.

9) ᴧcєɩ ᴧтoт zɩтoтĸ «It has come to me from you» (P.KRU 12, 29-30)

10) єĸɴᴧєɩ ᴧzoʏɴ ɴгпϫoєɩc ɴпpᴧqтooʏ ɴєɴнɩ єтммᴧʏ «You shall enter into and become owner of the quarter of that house» (P.KRU 12, 31-32); note also unassimilated nu before pi.

11) ᴧʏᴧϣc ᴧpoɩ «It was read out to me» (P.KRU 13, 67-68)

12) ᴧɩĸᴧᴧc ᴧʙoᴧ «I executed it» (P.KRU 13, 69)

The most consistent feature exhibited by Shenoute is the writing of epsilon before suffix pronouns and unaccented final syllables.

| є before suffixes | ||

zɩтooтєĸ > zɩтooтĸ ɴzнтєq > ɴzнтq ᴧʏoϣєc > ᴧʏoϣc | «from you» «in it» «it was read out» | P.KRU 1, 75; 4, 45; 54, 11 P.KRU 1, 108; 2, 51; 4, 83; 54.18 P.KRU 1, 109; 4; 84 |

| є before unaccented syllables | ||

ɷpєĸ > ɷpĸ ɷpєϫ > ɷpϫ opєϫ > opϫ | «swear» «surety» «secure» | P.KRU 1, 37; 2, 14; 4, 23 P.KRU 1, 104; 2, 47; 4, 81; 54, 16 P.KRU 1, 106; 2, 48; 4, 82 |

Neither this use of epsilon by Shenoute nor unassimilated nu by Shmentsnêy, as stated above, are typical Theban dialectal features23. What this might signify for the potential origin of their family is beyond the scope of the current discussion (if, in fact, it has any significance). What is important here is that the two scribes do not share each other’s orthographic idiosyncrasies.

Did Shmentsnêy train Shenoute?

The evidence from their surviving documents suggests that Shmentsnêy did not train his son, Shenoute, how to compose legal documents. This is not to say that he played no role in his son’s education, especially in its initial stages for which we have no evidence, but that he did not provide the model to which his son turned to as a professional. The question, then, is who did train Shenoute?

Returning to the onomastic evidence, if we look at the other groups, we see that as a whole the younger generation’s work does not resemble that of their fathers’ (again, this has been determined through personal autopsy of the documents, images of which are unpublished). Instead, the general pattern is that the work of the younger generation (i.e. David son of Psate, Aristophanes son of Johannes, and Johannake son of Johannes) are remarkably the same and that they share many similarities with other of their contemporaries, including Kyriakos son of Demetrios (P.KRU 28, 50) and Souai son of Philotheos (P.KRU 6, 71, 115). Their palaeographic similarities extend to their use of formulae, the structure of their documents, and their orthography. Shenoute’s work has more points in common with that of these scribes, with whom he was a contemporary, than his father.

In light of this, what does seem clear is that, while fathers may have played a pivotal role in determining the future career of their sons, they were not involved in the practical process. While this removes one possible source of higher education in the village, i.e. family, it instead highlights the existence of «schools of practice», in which multiple individuals received the same training. How many such schools existed, who belonged to these schools, and who was responsible for providing the training, is still to be determined.

Bibliography

Biedenkopf-Ziehner, A. (2001), Koptische Schenkungsurkunden aus der Thebais: Formeln und Topoi der Urkunden, Aussagen der Urkunden, Indices (Göttinger Orientforschungen IV, Reihe Ägypten 41, Wiesbaden).

Boud’hors, A. (2004), Pages chrétiennes d’Egypte: les manuscripts des Coptes (Paris).

Boulard, L. (1912), «La vente dans les actes coptes», in Etudes d’histoire juridique offertes à Paul Frédéric Girard (par ses élèves) (Paris) 1-94.

Bucking, S. (2007), «Scribes and Schoolmasters? On Contextualizing Coptic and Greek Ostraca Excavated at the Monastery of Epiphanius», Journal of Coptic Studies 9, 21-47.

Burkard, G./Mackendsen, M./Polz, D. (2003), «Die spätantike/koptische Klosteranlage Deir el-Bachit in Dra’ Abu el-Naga (Oberägypten): Erster Vorbericht», MDAIK 59, 41-66, Taf. 6-13.

Cribiore, R. (2001), Gymnastics of the Mind: Greek Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt (Princeton/Oxford).

Cromwell, J. (2010), «Aristophanes son of Johannes: an 8th century bilingual scribe? A study in graphic bilingualism», in Papaconstantinou, A. (ed.), The Multilingual Experience in Egypt, from the Ptolemies to the Abbasids (Aldershot) 221-232.

Cromwell, J. (2011), «A Case of Sibling Scribes in Coptic Thebes», Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology 22, 67-82.

Hölscher, U. (1934), The Excavation of Medinet Habu I: General Plans and Views (OIP 21, Chicago).

Hölscher, U. (1954), The Excavation of Medinet Habu V: Post-Ramessid Remains (OIP 66, Chicago).

Till, W.C. (1962), Datierung und Prosopographie der koptischen Urkunden aus Theben (Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse 240, Wien).

Wilfong, T. (2002), Women from Jeme: Lives in a Coptic Town in Late Antique Egypt (Ann Arbor).

____________

1 For an overview of the village, built within the mortuary temple complex of Ramesses III, Medinet Habu, on the west bank of Thebes, see Holscher (1954) 45-57 and Wilfong (2002) 1-22.

2 Hardly any images of the Jeme papyri are published. However, those that are provide some indication of the range found: see P.CLT pl. I-III (P.CLT 1), by Psate son of Pisrael; P.CLT pl. IV (P. CLT 2), by Theodoros son of Moses; P.CLT pl. V (P.CLT 3) and Boud’hors (1996) 65 (P.KRU 40), both by Aristophanes son of Johannes.

3 This has been highlighted by Cribiore in her study on education in Greco-Roman Egypt; Cribiore (2001) 17.

4 On the monastery of Epiphanius, see the recent discussion by Bucking (2007). The existence of a school at Deir el-Bakhit is indicated by the number of school exercises found at the site; see Bukkard/Mackendsen/Polz (2003).

5 By the time of Hölscher’s work at Medinet Habu in the 1920s, domestic architecture survived only to the north and west of the temple. The extent of the remains is shown by the plan of the site produced in Holscher (1934) pl. 32. The superstructures extant at this time are visible in photographs taken at the time (reproduced in Wilfong [2002] pl. 1).

6 The role played by specific teachers is discussed throughout Cribiore (2001).

7 37 scribes are listed in P.KRU Index V; a more comprehensive list of Jeme scribes is yet to be compiled.

8 While Johannes is a very common name, as attested by the number of entries in Till (1962) 107-112, Johannes son of Lazarus is the only scribe in P.KRU with this name. Further, his dates (from 698 to the late 730s) predate those of Aristophanes (724-756) and Joannake (mid-720s). For both of these reasons, this Johannes is most likely the father of the two younger scribes. For a discussion of Aristophanes and Johannake as siblings, see Cromwell (2011).

9 The name Shmentsnêy is written variously in Coptic with the Coptic letter shai and the Greek letter chi, but as this is an Egyptian name, for consistency I have transcribed it throughout as Shmentsnêy rather than Chmentsnêy.

10 Cribiore (2001) 105.

11 The dossier of Psate son of Pisrael and David son of Psate comprises 12 documents (Psate: P.CLT 1 and 5; P.KRU 23, 36, 37 and 44; David: P.KRU 5, 19, 24, 90, 98 and 102); that of Johannes son of Lazarus and Joannake and Aristophanes sons of Johannes comprises 32 documents (Johannes: P.CLT 8, P.KRU 21, 35, 38, 42 and 51; Joannake: P.KRU 45 and 46; Aristophanes: P.Bal. 130 Appendix, P.CLT 3, P.KRU 8, 10, 11, 14, 15, 17, 25, 26, 27, 33, 39, 40, 41, 43, 47, 48, 52, 53, 58, 87, 95 + 101 [these are, in fact, two parts of the same document, based on my personal research on Aristophanes’ dossier] and 103). This is, again, only including the documents written on papyrus.

12 P.KRU 1 is not signed, but on palaeographic and linguistic grounds it is certainly written by Shmentsnêy.

13 Shenoute does not use the title διάκονοc in his notation (example 6), but in P.KRU 5.67, where he acts as witness to the document.

14 These dates are taken from Till (1962) 69-70 and 208-209. It is possible that Shenoute’s dates can be lowered by fifteen years, but I believe this is unlikely.

15 For a treatment of this practice, as used by the scribe Aristophanes son of Johannes, see Cromwell (2010).

16 ᴧɩтɩ пᴧoʏoєɩ єpoc єɩoʏɷϣ zɴoʏcʙɷ ɴoʏɷт мɴoʏᴧoгɩcмoc єɴᴧтпooɴq єʙoᴧ мɴoʏпɩcтɩc єcopx мɴoʏᴧɩᴧɴoɩcɩc єccoʏтɷɴ xɷpɩc ᴧᴧᴧʏ ɴĸpoq zɩzoтє zɩxɩɴϭoɴc zɩᴧпᴧтн zɩcʏɴᴧpпᴧгн zɩпєpɩгpᴧϕн ємɴoʏᴧɴᴧгĸн ɴoʏɷт ĸн ɴᴧɩ єzpᴧɩ ᴧᴧᴧᴧ єɴ пᴧcн ᴧгᴧɵн ĸᴧᴧн пpoєpᴧɩcн «I have undertaken it, and I desire through one mind and an unchangeable thought, a firm belief and correct purpose, without any compulsion, fear, violence, deceit, artifice, circumvention and a single constraint set against me, but with all good and proper free choice» (P.KRU 14, 20-26).

17 This is rare, but not without parallel; see P.KRU 44, 115-117.

18 See Boulard (1912) 31-34; Biedenkopf-Ziehner (2001) 17-18.

19 As Shenoute writes his notation in Greek they are also published separately in SB I. P.KRU 2 = SB I 5556: ἐγὼ Cενούθ(ηc) τοῦ υἱο(ῦ) μακ(αρίου) Χμντcνήυ ἐλαχ(ίcτου) πρε(cβυτέρου) ἀπὸ κάcτρου Μεμνονίου ἔγραψα. P.KRU 4 = SB I 5557: ἐγὼ Cενούθ(ηc) υἱο(ῦ) μακ(αρίου) Χμτcνήυ ἐλαχ(ίcτου) πρε(cβυτέρου) ἀπὸ κάcτρου Μεμνονίου ἔγραψα. P.KRU 54 = SB I 5585: ἐγὼ Cενούθ(ηc) υἱὸ(ῦ) μακ(αρίου) Χμτοcνήυ ἐλαχ(ιcτοc) πρε(cβύτεροc) ἔγραψα. With P.KRU 4 and 54, ἐγώ is a correction of 6ro and ἔγραψα of єгpᴧψᴧc, where -c appears to be the suffixed pronominal object (referring to тпpᴧcɩc, ἡ πρᾶcιc), and thus a very unusual Graeco-Coptic mix.

20 The other individual is Christopher son of Demetrios, the scribe of P.KRU 57.

21 See P.Bal., p. 100.

22 See P.Bal., p. 69, and especially P.Epiph. I, p. 236.

23 For the most detailed study of the Theban dialect in non-literary papyri, see P.Epiph. I, p. 232-256. I would like to thank Anne Boud’hors (Paris) for discussion about these features.