The Bodmer Menander and the comic fragments

I.

In the preface to the second edition of his Roman Laughter (Oxford, 1987), Erich Segal refers to what he calls the Menandrian explosion: «What was once», he says, «a collection merely of aphorisms and a few long fragments is now a full-fledged Oxford Text»1. Or – let us put it in another way – what once fitted comfortably into a single volume of the Loeb Classical Library is now expected to fill three2.

I have in mind a Cambridge colleague (not a classical scholar) whose 100th birthday fell in August 1988. He will therefore have been of undergraduate age when the first substantial accession of text to Menander came with the publication of the Cairo codex in 1907. Half a century later, give or take a few months, came the first wave of Erich Segal’s modern explosion, with the publication of the Dyskolos from the Bodmer codex, the event we are now celebrating. Time does pass. Anyone who was an undergraduate in 1957-1958 is now rising 50. In this third age of Menandrian rediscovery, seen against the span of the generations, we need not, I think, pause long to justify ourselves in a retrospect, particularly if the object of the retrospect is to gain insight and perspective for the next set of moves forward3.

The task I have set myself is to consider the impact of the Dyskolos (and indeed the other two plays represented in the Bodmer codex) on the interpretation of fragmentary texts. These may be substantial, or they may be short, and have more problems than words; they are texts which few people other than those professionally concerned with them would read for the sake of their individual attractions; but they do (or sometimes do) add up to make more sense of the history and development of Greek Comedy, a kind of literature which by the nature and variety of its descendants can claim to be among the most productive of any in the ancient world: of course, I mean not only stage plays, but their immediate relations on the cinema screen and on television as well as their more distant ones in the genre of the novel.

The first thing that happens with the recovery of a complete or substantially complete text is that we can look with hindsight on what we had of it before. I have no novelties to produce here; but a few selected examples of what happened when the new text came along are still worth recalling for the sake of what they can still teach us; they are what some people might call case-studies. But the process is not just a one-way traffic. The Bodmer codex is not only an exporter of information; it receives it too. The quotations which it absorbs sometimes in fact preserve, by indirect tradition, a text superior to this direct, if remote, descendant of Menander’s autograph copy. But once we have a complete text, or a substantial part of a text, other things happen as well. We can begin to see overall what idea of a lost play a set of fragments can give; we can see what happens when pieces of other copies are identified; and when we have, in bits and patches, more than one witness to the textual transmission, and not simply the product of the critics’ wrestlings with a single source. I have remarked elsewhere apropos of the growing number of fragments of copies of known Menander on the way that Antiquity sometimes seems to have an air of the Middle Ages4.

Thirty years of study by a considerable number of scholars in many parts of the world have certainly produced some useful editorial lessons. One could easily spend a whole session in discussing them, and in arguing the merits, when it comes to gappy passages, of minimal, medium or extensively conjectural restoration. I do not want to imply, if I move on to another class of discoveries, either that we are proceeding in historical order or that we are proceeding in some kind of rank order, from basic to elevated. I should rather want to argue that Menandrian criticism is particularly rich in examples of how different kinds of observation and different kinds of interpretation interact profitably with each other. But somewhere, in a broad group apart from the lessons learnt from the sources of our texts, we need to put the advances which the Bodmer plays have brought in the recognition of the conventions of comedy as literature. Among these, I include verbal formulae, such as occur at the end of prologue speeches, the end of the first act and elsewhere; I include also conventions of style or even of costume as perceived through references to it in the text; I include patterns of structure, such as acts; and I include recurrent themes and motifs. In order to make absolutely sure that I have left nothing out, I am tempted to adapt a formula which University scholarship candidates in my day used to be encouraged to put at the end of their applications: «… and I hereby apply for any other award for which I may be eligible»; or (what is rather like it) the prayer formula «… or by any other name if you prefer it». The kind of insight that complete texts bring to fragmentary ones is, in my experience, quite unpredictable.

In order to prevent this presentation getting completely out of hand (and it may have given a sense that it was threatening to do that), I shall move after exemplifying some of the topics I have mentioned from our known texts to two papyrus fragments from Oxyrhynchus in the care of the Egypt Exploration Society which are now on their way to publication in Oxyrhynchus Papyri. In doing this, I am grateful both to the Egypt Exploration Society and to the late Sir Eric Turner, who passed on to me the notes he had used for a preliminary discussion of these pieces which was held in the Institute of Classical Studies in his last session there, in 1977-1978. That does not say that Sir Eric would always have approved or that anyone else is expected always to approve, of the ideas which are here attached to the fragments.

II.

The preface to the second volume of the Teubner text of Menander, that of the plays known from quotations, was dated by Alfred Körte in 1943. Only after a series of misfortunes and delays, and much hard work by Andreas Thierfelder, did it finally appear in 1953; the second, revised edition was prepared in the very context of the rediscovery of the Dyskolos, when the first edition had already gone out of print. Those of us whose copies are now near disintegration can bear out the fulfilment of Professor Thierfelder’s modestly expressed hope that the book would be useful in work on the new material5. It was.

Körte’s text printed twelve quotations as fragments of the Dyskolos amounting between them to 43 lines or part-lines, counting in one single-word citation; and in addition he referred (rightly, as it turned out) to his fr. 677, βούλει τι, Κνήμων; εἷπέ μοι, which is the beginning of Dyskolos 691.

It is perhaps still worth reminding ourselves, those of us who constantly refer to lost plays, how very little we really know when what we have is (let us say) a four-per-cent sample of the text, cited for a variety of reasons by the anthologist, the antiquarian, the scholarly commentator, the grammarian or the lexicographer – for reasons which very rarely have anything to do with the principal content of the piece or its dramatic qualities.

Without going into exhaustive detail, it is worth pursuing the audit a little further. Three of the twelve fragments in Körte are bogus, namely nos 123, 124 and 126, in that a garbling of the sources of one kind or another made them appear to belong to the play when in fact they do not6. Three out of twelve is an alarmingly high proportion. If it seems all too easy to be wise after the event, the answer is that it is better to be wise after the event than not to be wise at all.

But more: others of these verses are corrupt. The most amusing example is fragment 122, quoted by a commentator on Euripides, Andromache, which was read as «I suppose one cannot escape a relationship, brother-in-law», οὐϰ ἔνεστ’ ἴσως φυγεῖν / οἰϰειότητα, δᾶερ – until the brother-in-law was dragged away from the spurious protection of οἰϰειότητα to become, by the light of the Bodmer codex at Dyskolos 240, the vocative not of δαήρ but of the common slave-name Δαος, who is being addressed by Gorgias at this point. Sometimes there is a gain from an improvement in our knowledge of the quoting sources. This is true at Dyskolos 50, where at the time of the editio princeps we depended for our text of Ammonius on Valckenaer’s edition of 1822. «What? You saw a girl here, a freeborn girl… and came away in love with her at first sight…» τί φήις; ἰδὼν ἐνταῦθα παῖδ’ ἐλευθέραν… ἐνταῦθα is what the Bodmer codex has. The quotation in Ammonius, Körte’s fr. 120, had suffered a number of troubles, and in fact could give no more than a misleading idea of what was being said; but from the general mess Valckenaer extracted ἐνθένδε as a conjecture for his sources’ ἔνθεν γε. Lloyd-Jones adopted this in his Oxford Text of 1960, with acknowledgement to Paul Maas; I myself in the commentary published in 1965, was hesitant, describing the conjecture as «a long shot but possibly a true one». It is now less of a long shot, since Nickau’s edition of Ammonius of 1966 has established that ἐνθένδε is in fact a transmitted reading; Sandbach accepts it, and gives his reasons in a full note; Jacques (19762) stays with ένταΰθα. If, in face of this, the conservative critic could do with a crumb of comfort, it is found at the end of Körte’s fr. 117, which is a quotation of part of Knemon’s tirade against extravagant sacrifices at Dyskolos 442-455. It begins in mid-verse in 447, and ends in 453 with his remark that having offered to the gods parts of the animal which are uneatable, «they swallow the rest themselves» αὐτοὶ τἇλλα ϰαταπίνουσι, one syllable short of a line-ending. Of course, Bentley could put that right, and so could Dobree: sed nil mutandum, in fine versus potest alterius personae φεῦ similisve interiectio fuisse, remarks Körte after Kaibel. The word is γραῦ.

Very many more illustrations could be given; but these may be enough to recall to us afresh how delicate an affair the treatment of fragments can be. Their editors have their successes and failures, like the rest of us; but one result of the recovery of continuous text in quantity is that it shows the measure of one’s debts as a perennial consumer of fragments to those who review the existing collections and add more by laborious research, who not only track through the very scattered nebula of secondary literature which fragments accumulate, but whose work often involves new collation and checking of the manuscripts of the primary sources. Before leaving this part of our topic, let us recall how much further it extends itself. When we recover continuous text, we can test the set of quotations that purport to represent it; but we also enlarge that set by recruiting into the text other material which could not previously be identified; and once it is identified, similar points of interest arise. But in fact, from the point of view of textual history, one of the most striking results of the recovery of the Dyskolos is the confrontation between the text of the Bodmer codex at 797-812 and the sixteen lines offered by Stobaeus which are Körte’s fr. 116. The passage has had ample discussion, to which we need not add here. The point for us to take is that this kind of variation, no matter what editorial choice you make, shows that we are in the presence of deliberate remodelling of the text, and not only the kinds of confusion which most of us would class as miscopying7.

When we come to papyri, the examples of textual variation seem to grow in number almost every time a new scrap of a known play is recognized. Colin Austin, in his two volumes of text and ancillary commentary on Aspis and Samia (1969) gives a valuable collection of material from his study of the Bodmer text of these plays and the other sources from which they were in part previously known. But even tiny pieces spring surprises. I have in mind POslo 168, a small scrap of what had been taken to be prose, which was brilliantly recognized by J. Lenaerts as giving parts of the middles of Dyskolos 766-773. In 56 letters, or traces of them, there are four variants. Two of these confirm corrections to the Bodmer codex made in the first edition; one has a bearing on a line which in the Bodmer codex is both corrupt and somewhat damaged; the fourth gives us ἐν δὲ τούτωι ιῶι γένει for ἐν δὲ τούτωι ιῶι μέρει (767) as the Greek for something like «in this kind of affair», not with any great difference of sense, but with a certain disturbance to one’s liking for accuracy, whichever way the decision goes8.

What conclusions are to be drawn from all this? Perhaps that some of the earlier editors of Dyskolos were too cautious, clinging to their single source whenever it is alone – and it almost always is – as if to a lifeline. Not to cast aspersions on anyone else, that has in fact been the verdict of critics generally on a number of passages in my own text, which began life in 1958 and appeared in 1965. I could make a catalogue: but two unpopular decisions will perhaps do – first, in 230, the retention of IIαιανιστάς «Paean singers» as the designation of the chorus, with its improbable scansion, as opposed to the correction IIανιστάς (but, by the way, do we yet have another example of this word?); and second the acceptance of Getas, as speaker of «Hurry up, Plangon» and so on at 430, when Sostratos’ mother enters with her procession. This involves following the papyrus, and the first edition, against Ritchie’s idea that the mother herself has a small speaking part, which (with variants devised by others) has the general assent. On the other hand, if this is not too crude a way to put it, the fact that things can happen in texts does not of itself mean that here and here they have. The improved and improving knowledge of the behaviour (or misbehaviour) of the sources of Menander’s text does help greatly towards verifying critical suggestions when they are made; but it does not let us off from the task of looking for improbable truth alongside probable error. We shall be biassed, but we can hope that with more information our bias will more often be right.

III.

It is a fascinating reflection that many of the conventions of New Comedy that are now generally taken for granted were either first observed or first seen in their true light with the publication of the Dyskolos and the later accession of the two other Bodmer plays. In saying this, I do not in the least want to be unfair to the large number of excellent observations about Menander that were made before 1958, or even before 1907 – as, to take the earlier date, in the first edition of Friedrich Leo’s Plautinische Forschungen, in 18959. But an example or two will show what I mean. Twice in Plautus and once in Terence, the speaker of a prologue speech warns the audience not to expect details of the plot10. Since Plautus on other occasions writes prologue speeches which go into considerable detail, and Terence never mentions what is in the play at all, except in the course of controversy with his critics, these remarks have a particular Roman context of their own. They also have a background in Menander’s dramaturgy, as became clear from Dyskolos 45f: «These are the essentials; the details you shall see, if you like; and please like!», ταῦτ’] ἐστὶ τὰ ϰεφάλαια‧ τὰ ϰαθ’ ἕϰαστα δὲ / ὄψεσ]θ’ ἐὰν βούλησθε‧βουλήθητε δέ. Once the lines are recognized in the line endings from Sikyonios (-oi) which are numbered 23-24, we have our formula, and wait with lively anticipation for a new papyrus which will show us what Moschion said at the end of his longer exposition speech at the beginning of Samia.

The formula by which a chorus is introduced was known from the Cairo plays at Epitr. 33/169 ff and Perik. 71/261ff. It has antecedents in earlier drama; it has its analogues in Plautus and Terence, and the problems thereby arising need not hold us up here11. Dyskolos 230-232 produces a variant for a play with its own special setting in the country, with «Pan-revellers» instead of just a party of people who have been having a drink (as I have said above, my attempt to defend «Paean-singers» has elicited an almost total lack of response). Aspis 245ff adds one more variant, possibly because of the special circumstance that the play began with a «crowd scene»12. A new discovery of the 1980’s is the set of fragments of a comedy published by Klaus Maresch as PKöln 5.203, and augmented in 1987 by some more pieces in the same handwriting published as PKöln 6.243. These are some fragments on which several people present on this occasion have already published comments; and they have considerable fascination, with the figure of a lover who is a passionate serenader of a girl whom he has apparently not yet seen face-to-face13. I wish I could include among those present Konrad Gaiser, now sadly missed by his friends and correspondents in many countries, whose declining health forced him to say «no» to an invitation to take part. Professor Gaiser was much attracted by the possibility of accommodating the new pieces to his immensely detailed and ingenious reconstruction of Menander’s Hydria14 One of the newer pieces has a reference to a chorus (a + b, 16 χορός τις, ὡς ἔοιϰ[ε), followed after one more line, by ΧΟΡΟϒ. As Maresch quite correctly remarks, the only known places where the chorus is referred to before ΧΟΡΟϒ are at the end of Act I (and, we can add, in all the places which are certainly not the end of Act I, it is not referred to). If a hypothesis is formed which postulates the occurrence of such a formula at the end of a later Act (which is what Gaiser wanted to do) the hypothesis is at considerable risk (I am sure, if he were here, he would be trying to persuade us to take the risk).

For all that, we should not see Menander as a slave to his own formulae. He is, as we have come to learn, a master of variatio when he chooses to be; but he does not make the mistake of supposing that every single thing has to be varied, or of neglecting the ways in which audiences of popular entertainment accept, and sometimes take positive pleasure in, things which are familiar and require no special perception. The formula with which plays end, inviting applause and invoking the laughter-loving maiden Victory, was already known from quotations and allusions before the Bodmer Dyskolos gave it us in vivo (so to speak) and not simply in vitro. Soon there followed other examples from papyri of Sikyonios and Misoumenos, as well as one from the end of a play lacking a definite identity, which was spotted on the basis of an odd column length and a few letters’ textual coincidence in independent observations by Carlo Corbato and myself15. So much for the convention. The examples so far are all in iambic trimeters. Samia, like Dyskolos, moves for the latter part of the fifth act into a long metre. In Dyskolos, iambic tetrameters are the vehicle for the ragging of Knemon. Once they have done with the old man, the slave and the cook see him off indoors in a mood of triumph, and they change back to trimeters to express this and to give the play its envoi. Not so in Samia. The last act, which begins in trimeters at 616, changes to trochaic tetrameters with the entry of Parmenon at 670, and stays in that metre to the end, producing a trochaic variant of the «laughter-loving maiden» lines to round it off.

These very simple structural conventions can, I think, be used to illustrate a whole aspect of Menander’s playwriting, which might be called the grammar and syntax of dramatic composition. This is something which, like the grammar and syntax of a language, we learn best in context. That is to say we learn it best from plays which have continuous text, so that we can then hope to recognize the same phenomena in much shorter or more broken fragments. Other more complicated conventions can be looked at in the same way: I mention by way of example David Bain’s study of asides, published in 1977; and K.B. Frost’s study of entrances and exits, published in 1988, in which, naturally, the new text given by the Bodmer plays is of fundamental importance16. We have already mentioned above the formulaic introduction of the chorus at the end of Act I. The whole topic of composition in acts and scenes (or, as I sometimes prefer to say, sequences) has had renewed attention in recent years, not least in a book-length study by Alain Blanchard, and in a number of contributions to the congress on Strutture della commedia greca organized by the Istituto nazionale del dramma antico in Syracuse in March 198717. It is proper to recall here that though much had been written for many years on the so-called «Law of the Five Acts», it was not until Dyskolos was published that we had a complete play of New Comedy in Greek which actually had five. It was that play, together with Aspis and Samia and some of the other discoveries of the later ‘60’s, that made it possible to grasp some of the ways in which Menander handled acts as compositional units and how he linked and distanced them. Only in 1986 was Dyskolos joined by another play with all its four examples of XOPOϒ verifiably present, namely by Epitrepontes, with the aid of a new fragment in Ann Arbor, Michigan18. Accordingly, in remarking on this topic in my commentary, published in 1965, I said that «since the Dyskolos is still the only fully preserved Menander in Greek, a minimal statement might be that the other remains of him are consistent with the ‘five-act’ pattern of composition and do not warrant the assumption of any other»; in 1987, I found myself recalling that minimal statement and remarking how much stronger it is now than when it was made19.

What applies to our understanding of structure in Menander – that it is improved and ready for more improvement – applies also with various differences to the content of the plays, and to their handling of themes and motifs: in fact to topics which are central to other studies being presented on this occasion. Here I offer just two observations.

There are certain themes and motifs of comedy on which we have had for centuries a considerable accumulation of material. I shall of course mention the topic of cooks and the preparation of feasts, not least because it is in that subject-area that we place the fascinating piece of 50 lines on the wonderful fish silouros, which were first presented by Professor W.H. Willis in his address to the VIIIth International Congress of FIEC in Dublin in 198420. There is no cause for alarm: I am not about to claim that the piece is by Menander, or even by a close relation of his. One can read such extravaganzas and enjoy them, and the way in which cook-scenes were excerpted and anthologized suggests that people often did21. But it is in the Dyskolos above all, and the best preserved plays seen in the light of it, that one can relate such passages to the rest of the play and begin to consider their function and not just their immediate effect. «The flower in the vase» (as I said of Dysk. 797-812, mentioned above) «looks different, and sometimes is different, from the flower on the plant.»

Fragments cry out for context. So also (and this is my second observation) do illustrations of particular moments in plays (which are a kind of non-verbal fragment), or particular groups of terracottas which may represent leading characters or a cast. The remarkable set of scenes from Menander in the mosaics found at Chorapha in Mytilene were presented and discussed by Lilly Kahil in a paper in Entretiens Hardt 16 (1970), and given full publication in that same year in Antike Kunst, Beiheft 6, under the names of S. Charitonidis, L. Kahil and R. Ginouvès. It is fortunate, and fascinating, that some of these coincide with very well-known scenes, for instance the Arbitration in Epitrepontes, Act II; and the expulsion of Chrysis in Samia, Act III, where the Bodmer codex and the Cairo codex run in parallel. The comparison of text and illustration, where we have both, can throw light on both, and can give us some help when we have a less clear context from our fragments for the moment of the picture, or indeed when we have no context at all. But that is a whole other story22.

IV.

When all else is said, the first thing that anyone does on meeting a fragment for the first time is to try to make out the words, and what they mean, and how they fall into phrases and sentences. It is here that the build-up in documentation has been remarkable. I suppose some sort of assessment of its effects might be made if one were to take some sample first editions of new fragments and note how often the Bodmer plays are quoted for parallels. But that bibliometric device would not tell the whole story. Another dimension of it is revealed if one takes some of the studies of Menander’s language that have been made since the «Menandrian explosion» and reflects with gratitude what can now be done that was hardly capable of being done before – beginning, perhaps, with F.H. Sandbach’s study of «Menander’s manipulation of language for dramatic purposes» in Entretiens Hardt 16 (1970), which was in fact written under the immediate impact of the publication of the Bodmer Aspis and Samia23.

There is a sense in which anything one can absorb from reading and re-reading more Menander is likely to prove valuable in face of a new, possibly smallish, and possibly broken piece on papyrus. If I am asked whether this is an argument in favour of intuition in the criticism and interpretation of texts, the answer, with however many qualifications, is «yes». One has to start somewhere, and to borrow a phrase from Sir Denys Page (who would not miss just one), a useful start is to have the mind «open, but not empty». Intuitions can be right, wrong and unverifiable. The art of the game is in selecting as many as possible of the first class.

To be more concrete, let us speak for a moment about asyndeton24. One of the first notes I put together on the Dyskolos was on a passage in the prologue speech (19f): «… he had a horrible life; a daughter is born to him; still more so»; ἔζη ϰαϰῶς‧ θυγάτριον αὐτῶι γίνεται‧ ἔτι μᾶλλον. It seemed to me that there were three points worth remark. The first is that in a similar narrative in Terence, Adelphoe, we have (867): «… I took a wife; what misery I found in that; sons born; another worry»; duxi uxorem: quam ibi miseriam uidi! nati filii, alia cura. Since in the previous line a quotation shows that Terence is running literally close to Menander, we are likely to have something more than a chance parallel. The second observation, irrelevant to what we are engaged in here, is that a daughter, who will one day need a dowry, can be thought of as a particularly heavy burden. Much more than I said can be said on that topic – but to what effect on the balance of the commentary? The third observation I took from Edward Capps’ commentary on Epitrepontes 74-75/250-251 (33-34 in his numbering), namely «asyndeton is characteristic of Menander’s style, especially in narrative passages»; and I then went on to quote Demetrius, de elocutione 193f, a very well-known passage in which he contrasts Menander with Philemon, distinguishing the disjointed or acting style from the connected or reading style. The point of the anecdote is that a continuous play not only produces linguistic phenomena, it produces them in a way which invites reflection, comment and comparison, and it therefore both sheds and receives light. In my case, the particular bit of light shed by this passage of Dyskolos was on the prologue speech of the Sikyonios (-oi), when the speaker is telling the story of the girl and the slave on sale in the market (9f): ἠρώτα πόσου / ταῦτ’ ἐστιν, ἤϰουσεν, συνεχώρησ’…; «… and there he was, asking ‘How much are these? ‘; they told him; he agreed…» And then what? έπ[ρίατο, «he bought them» is both the logical end to the narration and typical of Menander, as we have seen, in its style25.

Let us move to two other passages, concerning features of style which are less easily recognized, especially in a broken context. The first is the vocative of self-address. Normally vocatives are a gift, often no doubt consciously offered by the dramatist, to those who follow the articulation of his dialogue, whether by ear or by eye. The latter category includes both ancient and modern readers; and one ancient reader and I, in common with a number of other people, were deceived at Dyskolos 214 by the words «Stop moaning, Sostratos», παύε θρηῶν, Σώστρατε. The Bodmer copy, by means of a name boldly written in the right-hand margin, explicitly indicates that the speaker is the slave Pyrrhias, whose presence on stage at this point is decidedly hard to explain. None the less, some of us managed; only to learn the truth too late when it was pointed out independently by Eugenio Grassi and T.B.L. Webster: Sostratos is speaking to himself, as it might be saying «Cheer up, old chap»26. One does learn. Given έ[π]άν[αγε, Σ]ώστρατε in a broken line of a soliloquy in the Dis Exapaton (23), it would be a brave man who would make the same mistake twice.

Speakers in Menander not only address themselves sometimes; they sometimes, without clear signals, quote other people’s words either to their faces, or in remembering what they said later. My first example is doubtful, though rather more so to others than to me. At Dyskolos 611, Sostratos enters in conversation with Gorgias, trying to persuade him to join the party: «I won’t have you not. ‘No, thank you’ – for Heaven’s sake who on earth refuses an invitation to lunch when a friend has made a sacrifice?» We are in the ill-charted land of bygone social conventions. The key words are πάντ’ ἔχομεν «We have all we need», which like καλῶς ἔχει can be a polite way of saying «No» – or so I believe, and I do not think that in the context an ancient audience would have found that hard to take.

Misoumenos presents some more complicated (and in part unresolved) problems of this kind. At 284, Getas enters, recalling to himself the quarrel he has witnessed between Thrasonides, Demeas and Krateia: «Lord Zeus, the cruelty of the pair of them, strange and barbarous…» As he relives this, quoting from both sides, he does not notice Kleinias following him around and interpolating comments. There are some nasty gaps, and by no means all the details are settled, but there is enough text (due in no small measure to Sir Eric Turner’s eyesight and judgement) for us to be clear what is happening. To conclude this discussion with a reminder that not everything in this imperfect world is within our grasp, we need only turn to Misoumenos 101-141, where at 132ff we have – or may have – a sequence of intercut dialogue and quotation of a similar kind, but its articulation is still elusive, as I think it must be without more text.

V.

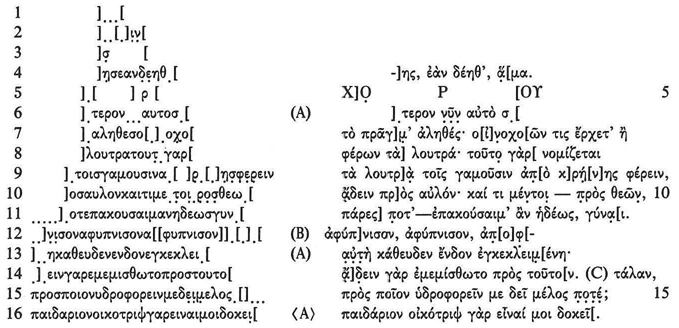

More text. I turn now to a transcript, with a conjecturally restored version in parallel, of a fragment which is to appear in Oxyrhynchus Papyri, probably in vol. 59, with which the editors are now engaged.

Let me first explain, and try to dispose of, some points which are not primary to our purpose. What we have is a scrap, overall 124x117 mm, with sixteen written lines from the foot of a column of a roll, the back being blank.

The piece is linked by its handwriting, as Sir Eric Turner had observed, with POxy 2654, though he had not yet seen it at the time of publishing that, piece. 2654 is identified by a quotation as being part of a copy of Menander, Karchedonios, and that identity is quite consistent with what can be made out of the content. The same copyist was at work in the small unassigned fragment published as PKöln 1.4, as its editor, Ludwig Koenen, and Turner agreed on comparing the two pieces. It is curious that both 2654 and the Cologne piece display two distinct hands or styles, which alternate without discernible reason; both have traces of editorial activity. Our piece is uniform in style with what Turner and Koenen call «Hand 1», and has only a correction made currente calamo. There is more to be said about the distinction between «Hand 1» and «Hand 2» than can or need be said here. The upshot of all this is that we have a piece which is very possibly but not necessarily Karchedonios. Koenen dates the writing to the first century B.C.; Turner’s view, to which I incline, is for first century A.D.

Detailed discussion of broken letters and doubtful readings is something that for our purposes we can also dispense with. Without that detail, and without (I hope) resting too much on unsupported guesswork, my idea is to suggest that there is enough of the text left for some primary observations to be made and shared; and I trust that they will be acceptable as appropriate to a commemoration of the Bodmer Dyskolos.

v. 13 leg., suppl. EGT; idem vv. 7, 10, 14 initia, et v. 11 fin.; cetera fere EWH, exempli gratia nonnulla

The clearest beginning I can offer is in line 15: «Whatever sort of song am I to have for my water-carrying?» In 8, a reference to λουτρά; and, following, a reference to «bringing water from the fountain for those marrying», make it (I think) plain that we have on stage an enactment of a loutrophoria, the bringing of pure water for a nuptial bath – from the fountain Kallirrhoe if the scene is in Athens27. There is a mention of an αύλός in 10. In 11, someone says «I’d be glad to hear, Madam». γύναι, though incomplete, seems to me inescapable; the reason for supplementing the beginning as I do does not affect the argument: it is that πρὸς θεῶν ought to introduce a more emphatic remark than one expressed by an optative with ἄν.

We thus have, at minimum, a woman carrying water, with a musical accompaniment of which (however seriously) she complains. There is also an interested bystander. From his comment in 14 «He is someone who was hired to sing in accompaniment to this one», we gather that there is both a piper and a singer. From 13 we gather that the bride-to-be, simply αὐτή, is inside in her bedroom, or so the speaker thinks.

I should like to suggest that at this point we have enough to make us think quite legitimately of a scene in Dyskolos of similar structure but quite different content – one which has been mentioned already, namely the scene at the beginning of Act III, when Menander brings in Sostratos’ mother with a procession for a rustic sacrifice and party, and there is some music to salute Pan in the shape of a pipe tune. Now the precise attribution of lines to speakers there may still be arguable28. But the pattern of picturesque procession with commentator – in the Dyskolos, Knemon – is something recognizable; and it may not be too fanciful to be on the look out for a contrast between the angry old introvert misanthrope and the very enquiring, perhaps even busybodying, person in our piece.

Are we in fact at an act-beginning, as in Dyskolos? For the present, I am assuming so, though on grounds less solid than I should like. In the line numbered 5, there is a clear, precisely-written, rho in centre-column; the only other ink is a dot that might be anything, but placed where the first omicron might be if XOPOϒ were written spaced out as it commonly is. The line-spacing looks slightly wider than normal. But there is so little papyrus left (and what there is is partly abraded) that one cannot on any secure ground guarantee that this was not a written line like any other. For what it is worth, line 4, ending «… together, if need be» is not bad as the end of an exit line; it could even be instructions for the departure of the water-carrying party which will reappear at the beginning of the new Act29. And line 6 can be written as the start of a speech in several ways – too many for it to contribute verification. There, at all events, is what I can make of the facts.

Perhaps the most teasing of the new lines is line 12. The copyist appears to have begun by writing the word ἀφύπνισον three times. Twice was enough, as he saw. He then deleted all but the first alpha of the third repetition, and went on with a word which was perhaps ἀπόφερε, perhaps not. The word ἀφυπνίζειν, according to the dictionnaries, is normally transitive, though there is evidence for the development of an intransitive sense; it is not a normal word of fourth-century comedy, and may here have brought a slightly elevated tone30. If we do assume ἀφύπνισον, ἀφύπνισον… it is necessary to assume that the copyist set the line out from the column to the left by two letters (which is a normal practice when a change of metre comes)31. As to what the metre was, the word-division suggests fully resolved anapaests, which some people call proceleusmatics: the continuation could have been ἀπόφερε ϰάματον or even something longer. If the lady expected regular dimeters, or something else she might walk to with reasonable decorum, her protest is not surprising. Agitation and flutter are readily recognizable in runs of short syllables of this kind; and according to one ancient metrician, proceleusmatics are typical of the entry of choruses of satyrs32.

The Dyskolos scene uses music in the form of a traditional pipetune. We do not know how long the musical sequence in this scene went on, but it is more elaborate in using song as well, and in making a point about the character of the song. Perhaps more elaborate still in its use of music is the scene from Theophoroumene, Act II, for which we have some scrappy papyrus text as well as the derivatives of what must have been a famous representation in art33. There a tune from the cult of Cybele, the Great Mother, is played on the pipe, with accompaniment from cymbals and tambourine, in order to test whether the girl supposed to be possessed by the goddess was genuinely so possessed, in which case she could be expected to respond to it, as (apparently) she did. Taken together with a quotation of the song before the temple of Apollo, which we find quoted from the beginning of Leukadia (258 K-T), this set of three passages seems to me to throw a fascinating gleam of light on what I will call the «naturalistic» use of music in Menander – music in contexts where music might occur in real life – as opposed to what one might label (anachronistically) the «operatic» use of music, present in a kind in the scene in iambic tetrameters performed to pipe-music in Dyskolos, Act V34. Presumably when we are told by an ancient metrician that Menander used resolved ithyphallics in the Phasma (and assuming that his text has not been garbled like some of those we considered earlier)35, this must be a scene of «naturalistic» music, like the new one, and the very rarity of lyric in Menander must raise the possibility that the two are the same. Once we allow that the link by handwriting is not decisive in identifying the new piece as Karchedonios, any play with a wedding-motif is a possible candidate; and a play with a possible wedding-song motif as well as a prominent wedding motif (which Phasma has) ought surely to be on the list.

There I should like, for the moment to leave my presentation of this piece, so far as the present occasion is concerned. If it is as interesting as I think it is, and if in future it provokes the discussion it deserves, it will owe something significant to the impetus given by the publication of the Bodmer Dyskolos, both in general, in the sense that that event inspired new studies and called forth fragments from their resting-places, whether above ground or below it; and in particular, in the sense that for me at least, a particular scene of that play gave a pattern for understanding, however imperfectly, a new one which seems to be one of its kin.

VI.

A passion for the wholly unknown is a powerful factor in keeping scholars going through the hard primary work of reading a new text and interpreting it; often the visible pinnacle of the iceberg floats on an unseen mass of necessary but discarded explorations and hypotheses, without which the pinnacle would not stand as it does above water. That is often an individual experience, and may be a collective one, as it was in a seminar held at the Institute of Classical Studies in London in 1959, whose speakers actually included the first editor of the Dyskolos, Victor Martin36.

New is new; it is not surprising if the heart sinks a little when one learns of the discovery of a papyrus which gives part of a play that we already know.

I have tried to illustrate earlier some of the ways in which that kind of new knowledge is also valuable; and I should like to end by touching on another gain we can sometimes make by combining data from more than one copy. I am thinking of bibliographical, not literary, discovery; but some of the questions raised by enquiries of this kind have, perhaps, their contribution to make to the very complicated question we ask, when we ask, as we go on doing: «Why did Menander disappear?»

Sir Eric Turner’s studies in The typology of the Early Codex, to quote the title of the notable book which appeared in Philadelphia in 1977, were pursued over several years. In that work, he lists and classifies many old friends together with their bibliographical kin, many of them, to most of us, very much less well known. Not least among the old friends is the Bodmer Menander (which has of course been the subject of much bibliographical discussion on its own); it will be found under no. 225.

It was with the aid of the Bodmer Aspis, and with Dr W.E.H. Cockle’s extraordinary skill and patience, that a scattered set of fragments could be put together to give a gappy leaf of another copy of the play. It does yield (Turner found) a number of textual variants. But they are not our concern here; they add to, but do not change, the general picture that we can now make out from elsewhere, as will be seen when the text finds its place in Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

What is our concern is the opportunity to consider, as a codex, one more of the impressive collections of plays in which Menander survived as late as he did. Let me run ahead of the story to say that the new leaf belongs to a class of tall and relatively narrow manuscripts in a sloping majuscule style of which the Cairo Menander is itself a leading member: Turner’s Group 5, Typology, pp. 16f.

The Cairo Menander, taking Turner’s figures (which are readily checked from the facsimile editions) has a standard page-size of 18x30 cm; it has a written area of 13x22 cm, and a number of lines per page which varies from 33 to 3837. The new leaf is closely comparable in overall dimensions. Its breadth can be reckoned at about 18.5-19 cm; there is a preserved height of 31.5 cm; the written area is 16x2538. But the writing is also larger and more spreading. The first side has 29 lines, Aspis 170-198, and the second has 33, Aspis 199-231. The figure of 29 needs comment, because while there are traces of one line lost by damage from the Bodmer copy after 193 (it will be called 193a), the new leaf completely omits 189, perhaps for no better reason than that 188 and 189 end ἔδει and δοϰεῖ respectively.

For comparison and contrast, we can put in brief descriptions of two more Menander manuscripts in the same typological group. PGenève Inv. 155 (Georgos) is a single leaf of unknown provenance acquired in Egypt in 1897. Turner calculates its overall original size at 18x30 cm, which can hardly be far out; the written area can be given approximately as 12x27 cm; the first side has 44 lines and the second 43. POxy 1013, of the Misoumenos, became reconstructable in terms of format when Turner had pieced together the codex which was in due time published as POxy 265639. It was probably a little taller and a little narrower (Turner gives 17 by 31-32 cm), and in a written area of approximately 12.5x27 cm it gets some 35-40 lines (the calculation is affected by the need to allow for XOPOϒ between 275 and 276).

We can accordingly say that the four manuscripts are quite closely similar in size and layout, but that the Geneva Georgos, with its 43-44 lines to a page, is considerably more economical, and the new Aspis rather less economical, with its 29 and 33, than the standard of 35-plus set by the other two.

These figures matter when its comes to calculating what else the manuscript contained, which we can do with the aid of surviving page-numbers. Our new leaf has numbers written twice at the top of each side, namely 142 (PMB) and 143 (PMΓ). The first side, that is the right-hand page, has an even, not an odd number: that is to say, most likely, that the numbering began on an inside leaf. So it did, apparently, with the Geneva Georgos, whose surviving leaf gives us pages 6 (ς) and 7 (Z)40. Not so, however, with the Cairo codex, in which Heros begins with a right-hand page numbered 29 (KΘ). Page 143 will be the last of the ninth quaternion.

So the Cairo codex, as everyone reckons, began with a relatively short play on its first 28 pages, something probably less than 1000 lines; then it went on with Heros, Epitrepontes, Perikeiromene and x, reaching its sixth quaternion (i.e. page 81) a dozen or so lines into Epitr. Act IV41. The codex represented by our new leaf would have needed six sides to take Aspis up to 177, and could then have accommodated about 4000 lines, or four plays before Aspis. If an upper limit of lines were taken, there might be just room for the first four Cairo plays, but there is no particular reason to choose that set of four rather than any other; and in fact such data as we have about combinations of plays suggest diversity in the collections rather than uniformity42. At all events, the codex was substantial. Even if Aspis were the last of five, it will have needed more pages than the sixteen of just one more quaternion. The Cairo codex, accepting Perikeiromene as next after Epitrepontes, can be calculated to have come to the end of the Perikeiromene in its eighth quaternion. The latter part of Samia, from 215 to the end, occupied a whole quaternion in the Cairo codex, as the Bodmer copy confirms. Samia cannot have come first in the Cairo codex, since it will not fit before Heros; nor can it have come immediately after Perikeiromene, unless the pattern of quaternions was disrupted. Play x, whether it was Fabula Incerta or another, must have intervened: in other words, the Cairo codex must have been considerably more substantial than Körte’s minimum figure of ten quaternions, 160 pages43. Even at this late date we are reckoning with the survival of Menander’s comedies in impressive collections.

«Even at this late date.» The dating of literary manuscripts from the fourth to the ninth centuries is a subject of notorious difficulty, since literary and documentary hands diverge in this period, and palaeographers who offer opinions are not always clear to the rest of us when they say «saec. v/vi» or the like: is this an alternative «fifth or sixth century» or does it mean «written about A.D. 500»? Guglielmo Cavallo and Herwig Maehler have recently published a fine collection of palaeographical specimens for the period, and have offered dating criteria based on careful structures of comparisons44. They would bring the date of the Cairo Menander down to the second half of the fifth century45. If that is right, a fifth-century date might also suit the Georgos in Geneva; the Misoumenos represented by POxy 1013 should be later; the sprawling hand of the new Oxyrhynchus codex with Aspis has, to my eye, the general air of a manuscript which has reached the end of its stylistic track, and it offers a number of particular features which Cavallo-Maehler note as signs of late date; it can be assigned to the second half of the sixth century, probably not earlier46. Even so, it may not be the latest Menander codex to survive. Of special interest, not least because in a quite different style, the so called «Coptic uncial» is the scrap of a codex from Hermoupolis, PBerol 21119, which has parts of Dyskolos 452-457 and 484-489, and was dated by Maehler, who first published it, as being «des 6.-7. Jahrhunderts»47.

What went wrong? Dioskoros of Aphroditopolis, the owner of the Cairo codex, eventually used his old Menander as a layer of protection for some papers he packed into a jar: by then it was already falling apart48. The Bodmer codex was heavily used, from the time of its writing in the third, or as some think the early fourth century, we cannot say over how many years; it was twice resewn, and on the last occasion so severely that it must have been virtually impossible to use as a book any more49. The fragments from St Catherine on Sinai in Leningrad were reused for writing another text in the eighth century, and ended up as material incorporated in a binding50. Our new leaf, with many other earlier copies of Menander, ended up on a rubbish heap in Oxyrhynchus. No new generation of copies arose; and that, for centuries, was all but the end. Let us hope it does not happen again. Among the best reasons for hope that it will not happen again is the existence of our hosts, and of those institutions world-wide which share their different but complementary interests: the Faculté des Lettres de l’Université de Genève and the Fondation Martin Bodmer; and with them, the Fondation Hardt.

____________

1 Menandri reliquiae selectae, ed. F.H. Sandbach (Oxford, 1972; 2nd ed., 1990).

2 F.G. Allinson (1921), 540pp; to be replaced by W.G. Arnott: vol. i (1979), Aspis-Epitrepontes, 526pp.

3 An outline of the progress of rediscovery with more references than are needed here is given in Cambridge History of Classical Literature vol. i (1985) 415-418; see also 779-783.

4 BICS 26 (1979) 81-87 at p. 84 = Actes du VIIe Congrès de la FIEC (Budapest, 1983) vol. ii, 547-555 at p. 552.

5 Menandri quae supersunt: pars altera, reliquiae apud veteres scriptores servatae, ed. A. Koerte; opus postumum retractavit, addenda ad utramque partem adiecit A. Thierfelder (Leipzig, 19531; 19592).

6 In 124, ὦ δυστυχής can be accepted as representing Dysk. 574 (or 919), but the quotation has been telescoped with one from Misoumenos, namely ὦ δυστυχής / τί οὐ ϰαθεύδεις; σύ μ’ ἀποκναίεις περιπατῶν, now (with the aid of POxy 3369) placed as Mis. A. 20 f. Something similar could have happened with fr. 123, if originally Dysk. 471f was quoted for the distinction between αἰτῶ and αἰτοῦμαι as well as the line elsewhere attested as from Hymnis (fr.410), οὐ πῦρ γὰρ αἰτῶν οὐδὲ λοπάδ’ αίτούμενος; and see Sandbach (OCT), p. 265 on «Samia frg. 1». Fr. 126, άνδρίας may be a garbled reference to Dysk. 677, where Sandbach’s note says what is needed.

7 O. Hense, RE «loannes Stobaios» 9.2 (1916) at col. 2583f. was quoted in my note on the passage for more examples of textual manipulation in the tradition behind the anthology. Some more recently available examples of confrontation between direct and indirect tradition can be found in the opening lines of Misoumenos: see the discussion by Turner in Oxyrhynchus Papyri 48 (1981) under nos 3368-3371, with further references given there. PTurner 5 (=Kitharistes fr. 1 Kö, 1 S), also published in 1981, throws a blink of somewhat lurid light on happenings within an indirect tradition.

8 J. Lenaerts, Papyrologica Bruxellensia 13 (1977) 23ff: see the paper quoted in n. 4 at pp. 83f/551f. Sandbach (OCT) vi-vii gives a telling list of examples.

9 See ChCLit (quoted n. 3) i. 416 n. 1.

10 P. Trin. 16f, Vid. l0f (fragmentary), T. Adel. 22ff. On this formula and other conventions discussed in the following paragraphs, see the more detailed discussion in H.-D. Blume’s paper above.

11 P. Ba. 107 and T.Heaut. 168ff, two much discussed passages which are mentioned together with some pre-Menandrean parallels in my notes on Dysk. 230-232.

12 See Entretiens Hardt 16 (1970) 12f, and Sandbach ad loc.

13 Maresch generously acknowledges contributions from a number of scholars in his discussion of the pieces published in PKöln 5, and updates the record in PKöln 6.

14 Konrad Gaiser, Menanders «Hydria»: eine hellenistiche Komödie und ihr Weg ins lateinische Mittelalter, published as Abhandlungen d. Heidelberger Akad. d. Wissenschaften, ph.-hist. Klasse, 1977.1

15 POxy 1239 = Colin Austin, Comicorum Graecorum Fragmenta in papyris reperta (1973), no. 249, where the appropriate references are given, including one to PHeid. 183 (= CGFP 218), the ending of Poseidippos, Apokleiomene, which I should still like to think is a deliberate echo of Menander: see on Dysk. 968f.

16 David Bain, Actors and Audience: a study of asides and related conventions in Greek drama (Oxford, 1977); K.B. Frost, Exits and Entrances in Menander (Oxford, 1988).

17 Alain Blanchard, Essai sur la composition des comédies de Ménandre (Paris, Les belles Lettres, 1983); Atti del XI Congresso Internazionale di studi sul dramma antico, now in Dioniso 57, 1987.

18 Μ. Gronewald, «Menander, Epitrepontes: neue Fragmente aus Akt III und IV», Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 66 (1986), 1-14.

19 Dyskolos of Menander, 41; and in the Proceedings quoted in n. 17 above at p. 302.

20 PDuke inv. F. 1984.1: there is a report by A. Panagopoulos of a later presentation in TO ΒΗΜΑ, 6 January 1985.

21 E.W. Handley, «A particle of Greek Comedy», Studies in honour of T.B.L. Webster, ed. J.H. Betts, J.T. Hooker and J.R. Green, vol. ii (Bristol, 1988) 107-110.

22 For instance: the Mytilene Plokion and the Mytilene Samia have a similar composition – given what we know of the situation in Samia how far can we use this with the remains of Plokion as evidence for the dispute between the old man Laches and his wife Krobyle?

Sometimes a famous scene proves to have generated a whole family of represntations in art, as is true of Theophoroumene (Charitonidis-Kahil-Ginouvès, 46-49) and of a play still to be identified, with outstanding representations in a relief in Naples (MN 6687; Bieber, Hist, of the Gk and Roman Theater2 324 and often elsewhere) and a cameo in Geneva (Musée d’art et d’histoire 21133): see J.R. Green, «Drunk again: a study in the iconography of the comic theater», AJA 89 (1985), 465-472 and Pls 52-54.

Accessions to the New Comedy material from works of art have been numerous and important since 1958: apart from the Mytilene mosaics, and the wall-painting of Sikyonioi [sic] in Ephesus (references in BICS 31 (1984), 315), they include a host of remarkable terracottas from Lipari, and not least among them a fine portrait of Menander himself: L. Bernabò Brea, Menandro e il teatro greco nelle terracotte liparesi (Genoa, SAGEP, 1981), with an admirable review by P.G. McG. Brown in Liverpool Classical Monthly 9.7 (July 1984), 108-112. The catalogue of Monuments illustrating New Comedy by T.B.L. Webster (2nd ed., BICS Suppl. 24, 1969) has been remade by J.R. Green and Axel Seeberg, and is currently being typeset; it will be more than twice the size of the volume it replaces.

23 Some more work from the intervening years (del Corno, Katsouris, Timer et al.) is cited in CHCLit (n. 3 above) i. 781f, and can be augmented from the surveys quoted there and below, p. 180. K.J. Dover, «Some types of abnormal word-order in Attic Comedy», CQ 35 (1985), 324-343 raises important questions of method, and considers in detail the status of the late placing of such words as γάρ, δέ and certain intensitive expressions (including oaths) in regard to current colloquial Attic: how artificial was comic dialogue?

24 M.G. Ferrero, «L’asindeto in Menandro», Dioniso 47 (1976), 82-106, should be quoted to rescue this discussion from its deliberate concentration on the two or three examples which suit the present purpose.

25 For comparison with this story, I should like to recall Turner in Entretiens Hardt 16 (1970), 138f, commenting on Sandbach’s ascription of the then newly published lines at Samia 98-101 to Nikeratos and not to Demeas.

26 See Frost (quoted n. 16) 45, and (cited there) J. Blundell, Menander and the monologue (Göttingen, 1980) 66-67.

27 See R. Ginouves, Balaneutike (1962), 265ff, who quotes representations in art; the relevant texts are admirably set out by R.E. Wycherley, Agora iii (1957), 13ff, and they include (no. 439) Harpocration under λουτροφόρος and λουτροφορεῖν, who remarks μέμνηνται δὲ τούτου τοῦ ἔθους οἱ κωμικοί.

28 See above under II, sub fin. The opening words,Πλάγγων, πορεύου θᾶττον, ϰτλ., are excellent for Sostratos’ mother, as Ritchie recognized: what is less clear, if we admit that, is how far she goes on, and whether her part may be taken by an extra voice in addition to the regular three. The contrast in treatment between my own text and discussion (1965) with that of Sandbach (1972; 1973); and of Jacques (19762); and of Arnott (1979) – to name no more – may perhaps mean that there are still considerations which escape us.

29 This pattern of linking over the discontinuity of the act-break was made plain by the accession of instances from the Bodmer plays; it is further documented by the Dis Exapaton fragment (in contrast to Plautus’ adaptation) and other discoveries since: see Entretiens Hardt 16 (1970) 10-18, together with contributions by H. Lloyd-Jones, myself and others to the Congress proceedings quoted in n. 17, where some further discussions are mentioned.

30 See E. Rhesus 23-5 συμμάχων, / Ἕϰτορ, βᾶθι πρὸς εὐνάς / ὄτρυνον ἔγχος αἴρειν, ὰφύπνισον. In this lyric passage the verb is transitive with object understood, and so it could be (depending on the sequel) in the present one. «Awake» (intr.) is quoted by LSJ from Later Greek, namely from Philostratus, vit. Apoll. 2. 36, but that usage might have been anticipated by Menander. From Comedy otherwise we have ἀφυπνίζεσθαι «wake up» twice: Cratinus, fab. inc. 306 K (=Eupolis, Marikas 205 K.- A.), anapaestic tetrameters; and Pherekrates, fab. inc. 191 K, Eupolideans. The normal word in Comedy, as elsewhere, is ἐγείρω, and it is found repeated in Com. Anon., PSI 1176 = Austin, CGFP 255.2 ὥστ’ ἔγειρ’ ἔγειρε δή / νῦν σε]αυτόν.

31 So in a near-contemporary copy of Aristophanes, Knights, which has hexameters among iambic trimeters: POxy 2545, Turner, GMAW2 no. 37, with discussion pp. 8 and 12.

32 See M.L. West, Gk Metre (1982) 123 with n. 109; and A.M. Dale in Coll. Papers (1969) 135f.

33 See Charitonidis-Kahil-Ginouvès, referred to above under III sub fin., with n. 22; texts in Sandbach (OCT) 143ff; more extended discussion in Handley, BICS 16 (1969) 88-101.

34 I hope the distinction is of use, even if it is not absolute: characters in opera (and for that matter in Plautus) sing both when in real life they would be singing and when in real life the would be speaking; and the song in Leukadia must owe something to its ancestor in Euripides, Ion.

35 See the passages set out in n. 6 above. The text is given by Körte, Phasma, frg. 3, from Caesius Bassus, Grammatici Latini vi. 255 Keil: what he means by tribrachs in ithyphallics can be exemplified metrically by ἀπόφερ’ ἀπόφερ’ αὐτήν  ; but not (it is to be admitted) without a certain temptation to fantasy.

; but not (it is to be admitted) without a certain temptation to fantasy.

36 See the Institute’s Annual Report for 1958-1959 and E. G. Timer, «Emendations to Menander’s Dyskolos», BICS 6 (1959), 61-72.

37 Turner, Typology, no. 227; see for these points and others to follow, The Cairo Codex of Menander (PCair J43227)a photographic edition… (preface by L. Koenen, London, 1978); Sandbach, Commentary, pp. 42-46; and Groenwald, quoted n. 16. Even in good facsimiles there can be an error of 5 % or more.

38 My own measurements from the papyrus; breadth involves an element of calculation, since we do not have the fully preserved leaf; written area is given as the normal, not the maximal.

39 PGenève inv. 155 [Pack2 1306] is Turner, Typology no. 230; POxy 1013 [Pack2 1314] is no. 233.

40 An act ending after line 96, nine lines after the end of the Geneva leaf, is given by the overlapping fragment PSI 100 [Pack2 1307]. Five pages at 43-44 lines each, say about 220 lines, if added to this, gives too much for one Act and not enough for two. The figure comes right for one Act if (as is generally done) we allow for two pages of prefatory matter. Hypothesis, list of characters and didascalia could perhaps take one; as for the rest, as an alternative to a Life of Menander (Wilamowitz), one might think of a portrait or other prefatory illustration.

41 Act III ends with line 509/699 (Groenwald, quoted n. 16); play x is hardly to be identified with Samia: see below.

42 Note Aspis in company with Misoumenos, PBerol 13932 + PSI 126 [Pack2 1318], a parchment codex of the fourth or fifth century, Turner, Typology, no. 235; Perikeiromene as second play in PLeipzig inv. 613 [Pack2 1303], a parchment codex of the third century with page numbers 51, 52, 61, 62 (NA, NB, ΞΑ, ΞΒ) added and then altered Turner, typology, no. 229; Epitrepontes in company with Phasma in the fragments of a fourth century parchment codex in Leningrad (388), Turner, typology, no. 227a. PSI 126 (Aspis) is Cavallo-Maehler 15b (n. 44 below).

43 See Sandbach (quoted n. 37), and earlier J.-M. Jacques, Ménandre: La Samienne (1971) lxx-lxxii, with a good reference to Christina Dedoussi’s discussion in ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΎ ΣAMIA (Athens, 1965) 3ff; Turner, typology, 83, does not deal with the problem of the gatherings when he says that Körte’s reconstruction «is now firmly supported by its agreement with the evidence of the Bodmer Codex for Samia».

44 G. Cavallo and H. Maehler, Greek bookhands of the early Byzantine period, A.D. 300-800 (London, Institute of Classical Studies, Bulletin Suppl. 47, 1987).

45 Op. cit., no. 16b.

46 Cavallo-Maehler in fact assign POxy 1013 to the first half or middle of the sixth century (Op. cit., no. 27c); in a seminar discussion in July 1988 Professor Maehler agreed with the presence of criteria for late date in the new Oxyrhynchus leaf, but thought it not as late as the seventh century: I am very grateful for his advice.

47 ZPE 4 (1969), 113.

48 Korte puts it nicely in the preface to vol. i of his Menander, p. viii: «erat igitur, cum Dioscurus chartas inutiles actis carissimis quasi coperculum addebat, non solum totius codicis compages dissoluta, sed etiam singulorum foliorum ordo plane turbatus.» I suppose that even with Cavallo-Maehler’s dating to the second half of the fifth century, the manuscript may by then have been a good hundred years old; for Dioskoros’s own style of bookhand, and some more references on him, see Cavallo-Maehler under nos 31a and 32a.

49 R. Kasser, Papyrus Bodmer XXV (Ménandre, La Samienne) (1969), 13-17; for the fourth century date, see Turner, Typology, 57 and Cavallo-Maehler under no. 5b.

50 Körte, Menander i, pp. xvii f., referring to a letter from Victor Jernstedt to Kaibel as well as to Jernstedt’s edition of the fragments (1891).