Poverty, crime and recidivism in twentieth century Britain

Myths and measures

Introduction

This paper offers a critical criminological account of the ways in which the discourse of recidivism has, throughout the twentieth century, been imbued with assumptions about the (allegedly causal) relationships between poverty, crime and punishment. It will be argued that the recidivist has overwhelmingly been constituted and reconstituted within the discursive contexts of poverty and social pathology – from the « dangerous poor » to the « underclass ».

The concept of recidivism has, in late twentieth century Britain, been reflected in a varied lexicon which has included the « recidivist », « repeat offender », « career criminal », « bail bandit » and, most recently, the « persistent young offender ». But while the language may change the official measurements of recidivism are constructed within a framework of « known offenders ». Measures against recidivists are similarly contingent on the identification of known (recorded) offences. As a consequence, some of the most successful recidivists – relatively rich « white-collar » criminals – whose offences remain undetected, remain beyond reproach or policy intervention.

Despite Tony Blair’s pledge, made in opposition in 1993 to « tackle crime and the causes of crime », New Labour in government has, so far, failed to reduce crime or address its (alleged) root causes. Rather, as we move into the twenty-first century, it stubbornly remains the case that « the rich get richer and the poor get prison »1 and criminal justice policy in Britain is, more than ever, focused on those who are (re) constituted as recidivists. Consequently, immediately after the 2001 UK General Election, Prime Minister Tony Blair signalled his intention to :

take further action to focus on the 100,000 most persistent offenders’ who were held to represent the « core » of the crime problem2.

This paper will go on to look at the risks of crime and recidivism among young people and will examine how the « persistent young offender » (PYO) has been registered in criminal justice and policy discourse. This analysis will then, briefly, be applied to research recently conducted with a local Youth Offending Team3 on patterns of offending amongst young people who are « looked after » in local authority care settings.

Overall, it will be argued that while the terminology may have shifted over time, the essential signifiers of the recidivist – pauperism, idleness, vice, « problem » families and youth – remain remarkably constant over the past two centuries. Such discourses still shape criminal justice policies. In these respects, it seems, history repeats itself. The paper will address the above issues in the following six sections : i) Poverty, crime and punishment : historical legacies ; ii) Models of the relationships between poverty, crime and punishment ; iii) Poverty and recidivism – measures of and against recidivism ; iv) Risks and Recidivism – the case of looked after young offenders ; v) Into the 21st Century – policies to tackle crime… and its causes ?

Poverty, crime and punishment : historical legacies

Contemporary images and assumptions about crime tap into a rich historical vein. From the « dangerous classes » of the nineteenth century to the « underclass » of the late twentieth, the poor have been portrayed as essentially criminogenic, posing a threat to both law and social order.

More than a century ago the connections between social deprivation and deviance were being explored by a range of social commentators. But poverty was not a unified or clearly defined status. Its features were not only economic : the lines which demarcated the « dangerous » and « dishonest » poor from the respectable working poor were often moral. The former were often seen as almost a « race apart », not only distinguished by their economic dependency, but by the degrading lifestyle which was believed to accompany that dependency – a lifestyle which promoted habitual offending. The dishonest poor (man) was thus :

distinguished from the civilised man by his repugnance to regular and continuons labour – by his want of providence in laying up a store for the future – by his inability to perceive consequences ever so slightly removed from immediate apprehensions – by his passion for stupefying herbs and roots and, where possible, for intoxicating fermented liquors4.

These themes were to be echoed more than a century later by the American guru of the « underclass » – Charles Murray – as he spoke of his childhood in lowa :

There were two kinds of poor people. One class of people was never even called « poor ». I came to understand that they simply lived on low incomes, as my own parents had done when they were young. There was another set of people, just a handful of them. These poor people didn’t just lack money. They were defined by their behaviour. Their homes were littered and unkempt. The men in the family were unable to hold a job for more than a few weeks at a time. Drunkenness was common. The children grew up ill-schooled and ill-behaved and contributed a disproportionate share of the local juvenile delinquents. To Henry Mayhew… they were the « dishonest poor »5.

Another theme evident here is that of the « problem family » which has come to embody a worrying fusion of disparate discourses around morality, dependency and crime. There is a discursive continuum, of sorts, which runs from « social problems » to « crime », within which the boundaries between the two become blurred, as it is assumed that « social problems » cause crime. But, this assumption completely fails to take into account that the most successful criminals (in terms of both the rewards of their crimes and their ability to escape punishment) are the rich : despite the divorce rate, lone parenthood, drunkenness and idleness of some of the « rich », these attributes are not regarded as a « social problem » and thus as causes of crime and recidivism.

One powerful influence which has long shaped discourses on crime, its causes and its perpetuation, centers on the stereotype of the criminogenic nature of female headed lone parent families. Clearly the stigma associated with bearing children out of wedlock has a long history in Britain, and these rich reservoirs were tapped in powerful discourses around lone mothers which (re) surfaced with a vengeance in the early 1990’s. Murray exemplified the essential ingredients of this stereotype :

Illegitimacy in the lower classes will continue to rise and, inevitably, life in lower class communities will continue to de-generate – more crime, more widespread drug and alcohol addiction, fewer marriages, more drop-out from work, more homelessness, more child neglect, fewer young people pulling themselves out of the slums, more young people tumbling in. (Murray, 1994, p. 18).

Murray’s discussion of the characteristics and consequences of what he termed the « New Rabble » eerily echoes views expressed twenty years earlier in a speech by the then Secretary of State for Social Services, Sir Keith Joseph, whose call for « the re-moralisation of public life » was uncomfortably dressed in the language of eugenics :

The balance of our population, our human stock is threatened […] a high and rising proportion of children are being born to mothers least fitted to bring children into the world. Many of these girls [from social classes 4 and 5] are unmarried, many are deserted or divorced or soon will be […]. They are producing problem children, the future unmarried mothers, delinquents, denizens of our borstals, sub-normal educational establishments, prisons, hostels for drifters. (sir Keith Joseph, 19th October 1974).

Again, the poor are portrayed as a « race apart », and they are responsible for breeding (quite literally), a plethora of social problems. At the forefront of these problems is crime and – inevitably – recidivism, which is constituted as a core aspect of the lives of the poor : it is a problem which they are seen to reproduce, from one generation to the next, primarily through the medium of single parent families.

Not only do such discourses blame the poor for their own poverty and thus for their own criminality, in so doing they also effectively eschew any structural or redistributive policy solutions to crime and its causes. At the same time, such individualised and « victim-blaming » perspectives alleging causal links between poverty, morality and crime signally fail to address the crimes of the rich. Moreover, where the allegedly criminogenic effects of lone motherhood are concerned, the evidential base for such negative stereotypes is weak : recent research has indicated that lone parent families are not, by definition, more liable to produce habitual criminals than other family forms6.

A further historical theme which informs contemporary understandings about the links between poverty, crime and punishment is the concept of the « problem area ». Contemporary exposés of inner city deprivation (and depravity) have many of the hallmarks of Mayhew’s description of the nineteenth century’s criminal areas, the « rookeries » : squalid housing, overcrowding, gambling, vice (notably prostitution), drunkenness, petty theft and hardened criminals, together with a powerful sense of « danger ». But the language associated with the rookeries had been, by the end of the twentieth century, modified by political events, notably the « riot » which occurred in several British cities in 1981, 1985 and 1991. One crucial dimension of the change in the conceptualization of the criminal areas has been the racialisation of the « urban crisis ».

Although keenly aware of the complexities involved in understanding the concepts of both « race » and the « city », Keith & Cross7 describe the ways in which « race » has been systematically used « to conjure up the urban crisis ». In general terms « Blackness […] has come to play a cautionary role »8 which may be likened to the nineteenth century fears of the crowd and the dangerous classes.

A prime example of this is clear in a speech made by the then Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Kenneth Newman, in the wake of the 1981 inner city « riots », where he coined the term « symbolic location » to describe what in essence were the (racialised) features of « problem » areas :

Throughout London there are locations where unemployed youth – often black youths – congregate ; where the sale and purchase of drugs, the exchange of stolen property and illegal drinking and gaming is not uncommon. The youths regard these locations as their territory. Police are viewed as intruders, the symbol of authority – largely white authority – in a society that is responsible for all their grievances about unemployment, prejudice and discrimination. They equate closely with criminal « rookeries » of Dickensian London […]. If allowed to continue, locations with these characteristics assume symbolic importance and negative symbolism of the inability of the police to maintain order. Their existence encourages law-breaking elsewhere, affects public perceptions of police effectiveness, heightens fear of crime and reinforces a phenomenon of urban decay9.

These views still resonate, twenty years on, in popular and political discourses, despite the fact that it became apparent in 1991 that « race » could not explain why riots erupted in predominantly white and/or « suburban » localities such as Blackbird Leys, Oxford and Scotswood, Tyneside. As Campbell indicated, the problem of the architecture and the residents in « problem areas » was becoming inseparable :

The theory of the underclass entered the vernacular together with the image of the estate. The two became synonymous in Britain10.

She goes on to summarise how the spatialisation of crime had changed by the 1990’s :

The collective gaze was directed at localities rather than, for example, the grandiose corporate frauds which vexed, and ultimately exhausted, the judicial system […] the « symbolic locations » shifted from […] the inner city […] to the edge of the city […]. These were places that were part of a mass landscape in Britain, estates were everywhere. But in the Nineties, estates came to mean crime11.

In the twenty-first century, criminal justice and social policy remains focused on the problem neighbourhood, but now deploys the language of social inclusion and neighbourhood renewal as key means of addressing crime – notably through the allegedly « joined-up » work of community safety strategies and the Neighbourhood Renewal Unit. The soft vocabulary of « social exclusion » replaced the hard « p » word (poverty – where usage is almost entirely confined to « child poverty »), and the lexicon of crime now encompasses a range of (non-criminal) activities under the umbrella of « anti-social behaviour ». The blurring of boundaries between the criminal and the social has implications for how crime and recidivism are to be addressed (as we will see below). But whilst criminal justice and social policies have been « shackled » together, it is notable that a higher degree of influence is accorded « to crime prevention – as opposed to poverty prevention »12.

Models of the relationships between poverty, crime and punishment

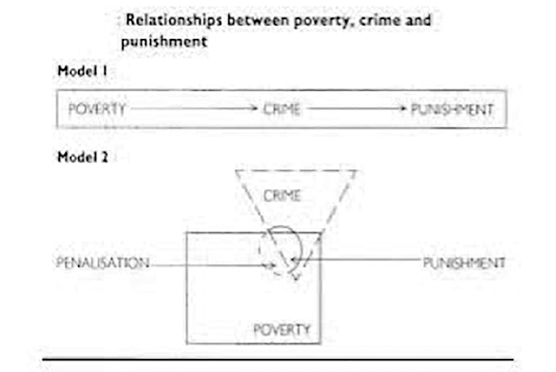

Tackling crime and recidivism inevitable means addressing their causes. In order to do this it is first necessary to explore the nature of the relationship between poverty, (re) offending and punishment. As argued elsewhere13, these relationships are more complex than politicians and popular mythologies would have us believe. Often seen as a simple two step (causal) process whereby poverty causes crime ; and crime leads to punishment, the « linear » view (represented in Figure 1 : Model 1 below) is flawed for a variety of reasons.

Firstly, while poverty may be one source of crime (as, for example in the crimes of prostitution and many social security frauds), it is an insufficient explanation for it – not least because much crime is committed by non-poor individuals and by wealthy corporations.

Secondly, the case of white-collar crime (and other « hidden » crimes) indicates not all crimes lead to punishment. As will be seen in 3 below, this means that measures of and against recidivism are inevitably limited to known offenders who are convicted in court.

Thirdly, not all punishment and official sanction is the result of crime : there are examples of alternative modes of state surveillance, regulation, policing and punishment which have penalizing effects on poor and excluded individuals and groups – notably, social security claimants, lone mothers, visible ethnic minorities, the young and the homeless14. Not all individuals who are regulated and penalised by the state have committed a crime against it.

An alternative way of looking at the relationship between poverty, crime and punishment is summarised in Figure 1 : Model 2 below15. Although the diagrammatic representation is in itself over-simplified, it nonetheless exposes the fallacy of the causal, linear view by presenting an altogether more complicated picture.

Figure 1

In this model, the phenomenon of crime is bounded by broken lines and is thus represented here as an « unknown quantity », as is the less tangible concept of « penalization », whereas we can quantify the extent of formal state punishment through the courts and at the end point of the prison. Formal punishment is largely reserved for those poorer groups who constitute the vast majority of the prison population (as we will see below). The non-poor are formally punished to a far less extent than their poorer counterparts and they are also less liable to suffer from various forms of state penalization (for example through welfare policing and regulation). As a result, the poor suffer more in terms of both : « hard » and « soft » policing ; and judicial punishment and broader – social and welfare – penalization.

But, crucially, there is evidence that high levels of social and economic inequality are positively related to crime16. It would follow that wage and social inequalities may contribute to crime and hence to the recidivism of the most vulnerable (marginalized) groups. This is echoed in the following comments of a long serving police officer giving his views on the causes of crime :

Why do people commit crime ? Come in Michael Howard : of course social deprivation plays a part. Yes, they’re going to get their dole money. But these people have had their hope taken away. Combine that with the fact that public morality just doesn’t exist. Putting it bluntly, if someone’s got a stolen telly in their front room, no-one round here gives a shit. But why should they ? […] How can you expect people with no future, on the poverty line, to worry about a stolen telly when the Chairman of British Gas got his whopping pay rise and his millions in share options, while his own employees are getting the sack ?17

In line with citizenship and social contract theories, it can be argued that if we expect people to obey the law and respect the rights and property of others, we should demonstrably provide them with : Laws that protect people equally ; Laws which are equitably applied to all ; Penalties for lawbreaking which are both justified and appropriate ; Penalties that are equally applied to all.

As the twentieth century drew to a close, were these conditions met in respect of British criminal justice ? It may be useful to address this through an example : we would probably expect that a young, unemployed, « black » male who admitted importing cannabis, cocaine and gay pornography from Amsterdam would feel the full force of the law in terms of swift, certain and justified punishment. But when these same crimes were committed by a white, middle aged, member of the European Parliament (as in the case of Tom Spencer MEP) they were written off merely as « an act of extreme folly », deserving only a financial penalty of £55018.

If, as Box suggested, inequality creates the conditions within which crime and recidivism flourish, then British social and criminal justice policies have been, and still are, pulling in very different directions. In relation to economic inequalities, not only does the UK have the most regressive personal tax regime in Europe, but we have a Prime Minister who is, at best, equivocal about the goal of redistribution and, at worst, dismissive of its implications. For example, speaking before the 2001 General Election, Tony Blair stated that « it is not a burning issue for me to make David Beckham earn less money ». But if Blair was serious about social justice and reducing social inequalities (which create conditions within which crime and recidivism flourish), this is exactly what would be required. Before the First World War Richard Tawney had perceptively commented that :

What thoughtful rich people call the problem of poverty, thinking poor people call, with equal justice, the problem of riches19.

Ninety years on, at the beginning of the twenty first century, these words are more relevant than ever as the gap between rich and poor has widened. Table 1 below indicates that in Britain it is the poorest who are disproportionately suffering the burden of taxation, while the richest fifth of the population benefit most.

Table 1 All taxes as a Percentage of Gross Income, 1999-2000, by household20

| Direct | Indirect | All taxes | |

| % | % | % | |

| All | 20.4 | 16.1 | 36.5 |

| Bottom Fifth | 11.5 | 29.8 | 41.4 |

| Top Fifth | 23.6 | 11.5 | 35.1 |

The first New Labour government has, therefore, failed to reverse the trend of widening inequality which had characterised the Thatcher/Major years : data from the Institute for Fiscal Studies indicates that from 1997 to 2000, the net income of the top 1/5th of the population increased at twice the rate of the poorest 1/5th21. Moreover, the annual Households Below Average income (HBAI) report confirms that the overall inequality gap was actually widening, with those not in work suffering particularly badly : two-thirds of those on low incomes lived in workless households22.

And so, while the dual-income Beckham’s are doing very nicely, 85 % of lone mothers on Income Support are currently struggling to repay Social Fund Loans23. And, while the salaries of top management in the UK exceed the rest of Europe by more than £100,000, the earnings of UK manufacturing workers are the lowest. In just two years the total remuneration packages of UK top managers have gone up in value by 29 %24.

In addition, there is still one law for the rich, another for the poor, in terms of criminal as well as social justice. To take one example, in 1998/9 there were 9,000 prosecutions for benefit fraud compared with just 32 for tax fraud, yet Lord Grabiner’s report on the hidden economy concluded that « for tax evasion, the current system seems to work well ». The system does indeed work well – for tax evaders ! Meanwhile, it works less well for the poor, and with scrougerphobia rife and utilised to justify ever tougher benefit regimes, there is little official recognition that up to £4 billion in benefits went unclaimed in 1999/200025.

Poverty and recidivism – measures of and against recidivism

The term « recidivism » may be interpreted in a variety of ways : on one hand it connotes elements of habitual offending which may be deeply imbued with the stereotypes discussed above in relation to the « dishonest poor ». On the other hand it is a term which requires some prior offender assessment and offence measurement before its application. While the first part of the paper has addressed the former, the second part addresses the latter issues.

A cursory search of the Home Office website reveals that the term « recidivism » is less used than « re-offending » and « reconviction » : these are very different terms. Most offending and re-offending goes unrecorded and undetected : the 2000 British Crime Survey indicated that only 23 % of offences against individuals and households end up in the recorded crime count26. Reconviction is defined as « a conviction of another offence during a specified follow-up period » (usually over a two year period), and it is derived from criminal conviction data. In this way convictions in court are taken as a proxy for offending and, hence, re-convictions as proxies for re-offending27.

Moreover, with rates of police detection running at a mere 24 % of recorded crimes in 2001, it is clear that convictions are an extremely imprecise measure of actual patterns of offending and recidivism. Rather, they display the offending patterns and characteristics of the small minority of offenders whose offences are reported, recorded, and who are subsequently apprehended and processed through the courts. These problematic issues, taken together with specific problems around the under-reporting, recording and processing of many « hidden » offences (such as white-collar/corporate offences, racial harassment and domestic violence), mean that current measurements of recidivism (and identification of recidivists) are deeply problematic.

Data on (re)convictions are also the source of problems. Such data derives mainly from the Home Office Offender Index, which is restricted to statistics on individuals convicted of standard list offences in courts in England and Wales. By contrast, the Police National Computer (PNC) data include dates of offences and information on cautions, reprimands and final warnings which offers the prospect for better quality information on recidivism in future, particularly where young offenders are concerned. However, significant data comparability issues are involved28 and research frequently cites « missing » entries in data fields29.

At the same time, data alone cannot tell us the « why » of recidivism, and if offenders « desist », it is difficult to establish which (if any) policy intervention may have led to this change30. In summary, what we can say with any authority about patterns of recidivism and recidivists is limited. However, these limitations have not halted a range of pronouncements about « criminal careers », the causes of re-offending and the design of measures to prevent it. On the basis of these « known reconvictions », the Home Office has stated the following :

We know that for ex-prisoners, unemployment doubles the chances of reconviction and homelessness increases the likelihood by two and a half times. Almost three fifths of those sent to prison are unemployed when sentenced ; and up to 90 % are estimated to leave prison without a job. About a third of prisoners lose their homes when they go to prison ; two fifths will be homeless on release31.

An analysis of reconvictions following community sentences32 reveals a similar but longer list of relevant social factors explaining reconviction which included : Drug use ; Employment ; Problems with accommodation ; Financial problems ; Peer group pressure ; Problems with relationships ; Being a past victim of violence.

But the key question remains « what is to be done with such information ? » Research studies suggest a range of ways in which the provision of education, accommodation, drug treatment and aftercare support may reduce re-offending, but the problem remains one of resourcing33.

As in the past, the causes of crime and recidivism are often « readoff » in terms of the characteristics of those who are known criminals and recidivists. Thus, research findings such as those above are used as a stick with which to beat the offenders themselves – nowhere is this more evident than in the case of young offenders.

Risks and Recidivism – the case of « looked after » young offenders

Just days after the 2001 general election, Tony Blair announced his intention to :

take further action to focus on the 100,000 most persistent offenders. They are responsible for half of all crime. They are the core of the crime problem in this country […]. Half are under 21, nearly two thirds are hard drug users, three quarters are out of work and more than a third were in care as children. Half have no qualifications at all and 45 % were excluded from school34.

For many, the solution to this problem lies not so much in penal responses to the behaviours of individual persistent offenders, but in addressing the conditions within which it is possible for (young) people to « slip through the net » and suffer such appalling and multiple deprivations. In relation to young offenders, a review of academic and policy literature reveals a long list of factors associated with youth offending35, the most frequently cited risk factors being : Truanting ; Exclusion from school ; Drug abuse ; Alcohol abuse ; Other substance abuse ; Anti-social or offending peers ; Known offenders in the home ; Poor parent-child relations ; Poor parental supervision ; Referral to mental health services ; On the « at risk » register ; Local Authority care.

For looked after children and young people, being convicted of criminal offences represents only one element of the (multiple) disadvantages suffered as the government itself acknowledges36 :

Between 1/4 and 1/3 of all rough sleepers have been looked after as children.

Looked after children (LAC) are 2½ times more likely to become teenage parents.

LAC are disproportionately likely to be unemployed.

LAC are disproportionately likely to end up in prison – 26 % of prisoners have been in care compared with 2 % of the population.

In recent research, we explored the risks and patterns of offending amongst looked after young people in one Shire County and one Unitary Authority in England37. Our research used the above list of risk factors for young offenders as a reference point for interviews with (multi)-agency staff. But when we asked staff working with looked after offenders what, in their view, were the most influential factors, almost all felt that the experience of care itself was the primary factor which pushed vulnerable looked after young people towards offending : our interviewees felt that many other elements of risk were the inevitable consequences of becoming looked after – for example, non-school attendance, antisocial peers, offenders « in the home » and poor parenting – albeit « corporate » parenting by local authorities.

Several interviewees discussed with us in some depth the case histories of certain looked after offenders to demonstrate the extreme and complex problems which led them into the looked after system and, thereafter, into offending. These problems included : bereavement, family breakdown, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, poor self-esteem, problematic family relationships, drug and alcohol abuse, self-harm and mental health problems. Clearly these chime with many of the risk factors cited in the research evidence already outlined.

But, once in care, many already-vulnerable young people were seen to be open to the influences of other looked after young people who may have a « contaminating » effect on them. As one interviewee noted, these effects can range from encouraging smoking, drug (ab) use, to creating a situation within which attending school is regarded as the exception, not the rule and where verbally and physically expressed anger – translated into aggressive behaviour or « kicking off » – becomes part of the daily routine. Typical staff comments included :

Everything is conducted at a scream – it’s the opposite of the calm they need. « It »’s about bars, locked doors and missiles – not a real « home ».

We found evidence (statistical and anecdotal) that the care experience itself can lead to the disproportionate criminalisation of looked after children and young people for offences which may not have been defined as criminal (or so reported) in other home/family contexts. For instance, one interviewee commented that,

if one of our [own] children were to kick in a door, or break a window in anger, our first reaction would probably not be to call in the police.

But this is precisely what happens in the context of some « care » establishments and, as a result, the experience of care and reporting practices of care staff significantly can shape the likelihood of vulnerable young people acquiring the negative status of « PYO ». Paradoxically, it is often the case that these looked after young people did not have any criminal record before entry into care. When examining reasons why looked after offenders had entered care in the first place, we found that most (43 of a total of 65) entered care between the ages of 13 and 15, with the most common reasons cited as : beyond parental control ; break-down of family relationships ; abuse or neglect.

More damaging still for these young people is the frequent disruption which offending has on their care placements : the young offenders interviewed felt that being moved to another care home following an incident of criminal damage or assault was « a punishment » in itself. While this is not officially the case, an analysis of care histories indicated that frequent disruption and changes in type and location of care placements were linked with incidents of offending (and their frequency).

The conclusions which follow from research such as this (while small scale) indicate that while official discourse around tackling PYO’s talks and acts « tough on crime », it is failing to address its causes. Many of the young offenders in our sample had experience of the whole range of local criminal justice interventions – from restorative conferences to final warnings and custody (with only the former two responses seen to have positive effects in addressing offending). But, at the level of national policy, few lessons are being learned in terms of the prevention of their offending – there is currently no national strategy for residential care or resources for Social Services Departments to implement one. In this way, there is a failure to address « the causes of crime » where the most vulnerable young people are concerned – those who have experience of local authority care.

Into the 21st Century – policies to tackle crime… and its causes ?

Reducing recidivism does not invariably mean « getting tough » with offenders in terms of tariff of penalty, particularly as there is no evidence whatever that prison « works » as a deterrent to crime and re-offending. Home Office data indicates an overall recidivism rate of 57 % (within a two year period) for offenders released in 1996, although for young males the figure was 76 %38.

Reducing recidivism may be more effectively addressed by engaging more positively with the existing community penalties which are available (especially education, employment and restorative justice programmes). At the same time, there is evidence from recent research on community penalties that these programmes may be further enhanced by effective enforcement (through letters, warnings etc.), which does serve to reduce reconvictions39.

On a pragmatic level, where recidivism is concerned, there is evidence that prison is no more effective than community penalties and is far more costly and damaging – for society and for individual prisoners. The prison population in February 2002 stood at a record 69,850 (an increase of 8 % on the previous year). Of these, 18 % of prisoners were on remand and 15,490 were from minority ethnic groups – a representation over three times higher than in the population as a whole40. Such figures beg important questions about remand and sentencing decisions which ultimately lead to the criminal justice system serving to filter in the poor, the excluded and vulnerable, while it filters out the better off.

In summary, I would cite the old saying that « history repeats itself because nobody listens ». If we are to listen and learn from the past, the key issue for me is that in order to address crime and recidivism, there is an urgent need to address their social, structural as well as individual causes. In its blueprint for criminal justice – « The Way Ahead » – the government offers, literally, a picture of how it is « tackling crime and the causes of crime »41. It is revealing that they offer a diagrammatic representation of a managerial and target oriented approach to the causes of crime which overwhelmingly42 fails to address any « causes » which might lie beyond the individual’s own personal failing : instead, the picture presents a virtuous circle of « joined-up » policies to address education and parenting failure, (un) employment and drug misuse.

But genuinely addressing the causes of crime will mean going well beyond individual pathologising and the targets, performance indicators and the new managerialism which has characterised both social and criminal justice policies over the past two decades. Instead it will involve a fundamental re-consideration of what criminal and social justice actually mean, and how they can be reconciled in policy and practice.

____________

1 R. Reiman, The Rich Get Rich and the Poor Get Prison, London, 1990.

2 Tony Blair, 30th May 2001.

3 D. Cook, M. Roberts, « Looked After Children and Offending » ; unpublished Report for Shropshire and Telford and Wrekin Youth Offending Team’, 2001.

4 Institute of Economic Affairs, « Charles Murray and the Underclass », Choice in Welfare, Series N° 33, London, 1996, p. 23.

5 C. Murray, « The Emerging British Underclass », Choices in Welfare, Series No 20, London, 1990.

6 H. Juby, D. Farrington, « Disentangling the link between disrupted families and delinquency », The British Journal of Criminology, N° 41, 2001, p. 37.

7 M. Keith, M. Cross, « Racism and the post modem city », in M. Keith and M. Cross (eds), Racism, the City and the State, London, 1993.

8 Ibid, p. 10.

9 Sir Kenneth Newman, quoted in P. Gilroy, J. Sim, « Law and order and the state of the Left », Capital and Class, N° 25, 1985.

10 B. Cambell, Goliath, London, 1993, p. 314.

11 Ibid, p. 317, emphasis in the original.

12 A. Crawford, Crime Prevention and Community Safety, London, 1998, p. 121.

13 D. Cook, Poverty, Crime and Punishment, London, 1997.

14 Ibid, and D. Garland, Punishment and Welfare, Aldershot, Gower, 1985.

15 D. Cook, Poverty, Crime and Punishment, op. cit., 1997, p. 59.

16 S. Box, Recession, Crime and Punishment, London, 1987.

17 Quoted in D. Rose, In the Name of the Law, London, 1996, pp. 94-95.

18 The Guardian, 1st February 1999.

19 Quoted in A. Sinfield, « Growing inequality increases the Need for Better Redistribution », Scottish Left Review, 1/6, April 2001.

20 Economic Trends, quoted in A. Sinfield, « Growing inequality increases the Need for Better Redistribution », op. cit.

21 Poverty : the Journal of the Child Poverty Action Group, N° 110, 2001, London, CPAG, p. 8.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Management Today’s Globol Survey, quoted in A. Sinfield, « Growing inequality Increases the Need for Better Redistribution », op. cit. ; and Lord Grabiner, The Informai Economy, London, 2000, p. 34.

25 Office of National Statistics, quoted in Poverty, N° 110, op. cit.

26 J. Prime, S. Whire, S. Liriano, K. Patel, Criminal Careers of those born between 1953 and 1978, Home Office Statistical Bulletin 4/10, London, Home Office, Section 1.4, 2001.

27 Ibid. and C. Friendship, A. Beech, K. D. Browne, « Reconviction as an outcome measure in research : a methodological note », British Journal of Criminology, N° 42, 2002, pp. 442-444.

28 J. Hine, A. Celnick, A One-Year Reconviction Study of Final Warnings, London, Home office, 2001.

29 J. Prime (et. al), Criminal Careers, op. cit., and C. Sarno, I. Hearnden, C. Hedderman, M. Hough, Working their way out of offending : an evaluation of two probation employment schemes, Home office Research Study N° 218, London, Home Office, 2001.

30 Ibid.

31 Home Office, Criminal Justice : the Way Ahead. Cm. 5074, London, Home Office, 2001, p. 47.

32 C. May, J. Wadwell, Enforcing Community Penalties : the relationship between enforcement and reconviction, Home Office Research Findings N° 155, London, Home Office, 2001.

33 For instance, see R. Webster, C. Hedderman, P. Turnbull, T. May, Building Bridges to Employment for Prisoners, Home Office Research Findings N° 226, London Home Office, 2001.

34 Speech made by Tony Blair, 30th May 2001.

35 For instance see S. Holdaway, N. Davidson, J. Dignan, R. Hammersley, J. Hine, and P. March, New strategies to address youth offending : the national evaluation of the pilot youth offending teams, Home Office RDS Occasional Paper N° 69, London, Home Office, 2001 ; and S. Campbell, V. Harrington, Youth Crime : findings from the 1998/9 youth lifestyles survey, Home Office RDS Research Findings N° 126, London, Home Office, 2000.

36 Cabinet Office, « Raising the Educational Attainment of Children in Care », Consultation Letter 12th July, 2001.

37 D. Cook, M. Roberts, Looked After Children and Youth Offending, confidential and unpublished research for a Youth Offending Team, 2001.

38 Reconvictions of Prisoners Discharged from Prison in 1996 ; see www.homeoffice. gov.uk/rds/prischap9.htm.

39 C. May, J. Wadwell, Enforcing Community Penalties, op. cit.

40 K. Rogers, Prison Population Brief England and Wales : February 2002, London, Home Office, 2002.

41 Home Office (2001b), op. cit., p. 22.

42 The only exception is the role the Neighbourhood Renewal Unit plays in this cycle – although I would argue that this seek to address « place poverty » and not the conditions of social and economic inequality within which it is (re) generated.