Persistence in crime and the impact of significant life-changes

A Pilot Study of Crewe, 18811

How oft since childhood have I wished I knew what lay behind the mystery of Crewe. It was a name on every cryptic mouth of those who talked of journeys North or South. And long before I knew what travelling meant Crewe was a word of magical content. Crewe stood for trains in splendour, pomp and glow – Trains – and aught else ? Ah, how I longed to know ; above this vast and clamour-echoing roof did old familiar stars look down, aloof ? If from this hurly, one adventured out and startled by strange stillness, stared about, what would one see ? Was there a town of Crewe nowise concerned about my passing through ? Did folk alight and live at Crewe ? How strange to settle down where others came to change. (Anonymous c.1922, cited in G. Bavington, B. Edge, H. Finch and C. McLean, Crewe : A portrait in old picture postcards, Brampton, 1987).

In 1895 John Jackson, a sixty year old sometime-labourer found himself in Crewe magistrates’ court on a charge of obtaining money by false pretences. Since that was an indictable offence, his case was dealt with at quarter sessions, where he was subsequently convicted and sentenced to imprisonment. This must have been a familiar scenario to John, since this was his thirteenth custodial sentence in a fourteen-year period.

His record of offending, which we have pieced together from petty and quarter sessions’ records, shows a man who moved around the northern industrial towns committing fairly serious offences, for which he was regularly imprisoned. Indeed, for this reason he could be used to prove two contradictory points. First, that « prison works » (since he is only at liberty for twenty-eight months in a fourteen-year period, his scope for committing offences was restricted). Second, that prison doesn’t work : since, sometimes lengthy, committals to prison have not proved to be rehabilitative.

As a prolific and apparently incorrigible offender, without regular legal employment, and committing serious offences of dishonesty, the Victorian elite2 would have quickly recognised him as a member of the criminal classes’. This putative criminal grouping supposedly existing in the heart of the purlieus and rookeries of the working class districts has cast a large shadow over criminological research for the last hundred years or so3.

The Victorian view that an increasingly large number of hard-core professional criminals committed the vast majority of serious offences has now largely been undermined by research on the temporary nature of criminal careers demonstrating that the majority of offenders do not maintain criminal identities over the whole of their lives. Historians have therefore moved away from calculating the numbers of the « criminal class » into more interesting areas of study, for example, analysing media representations of the serious offenders that impinged themselves on the public imagination, and the steps the Victorians took to control and discipline a largely mythical criminal population4. A study of John Jackson and his ilk would, presumably, inform that kind of research, by offering a more complete understanding of the life and offending behaviour of the more serious criminals throughout a period when they consumed the minds both of the public and the legislators. There are, however, methodological and theoretical problems with this kind of research. First, before the routine photography of prisoners and fingerprinting, it is impossible to trace particular serious offenders in the court records over time because of the use of aliases5. John Jackson had used four aliases that we are aware of, and may have other identities that were never discovered (especially as he moved across the country regularly). Indeed, since his antecedent history appears to suggest that he started to offend in his mid forties, which would be an atypical criminal career, we assume that the earlier offences were recorded under a different alias, and reside undiscovered in another records office somewhere. Secondly, because research has hitherto tended to focus on the more serious offenders, who were prosecuted by indictment, and were subject to habitual offender legislation, the vast majority of offenders have been ignored by historians (most offences were prosecuted by summary legislation at magistrates’ courts up and down the country). Although contemporary newspapers reported petty sessions court cases, and recorded the habitual drunkards and thieves who had been before the courts dozens of times6, there have been fewer systematic studies of the low-level persistent offender. This paper describes the contours of a substantial research project that attempts to redress this imbalance by focusing primarily on the offending trajectories of persistent offenders in a rapidly changing economic landscape.

The pilot study has brought people like William Fynn to our attention. Like John Jackson, Fynn was also a repeat offender, but of more minor offences (and for that reason he would not be subject to habitual criminal legislation since he had never committed two indictable offences7). However, he was convicted three times in 1881 of drunkenness, and drunken disorderliness ; his father was also prosecuted for non-payment of rates, and under the Education Act for not sending his child to school (Thomas, age thirteen, was working as a factory labourer) ; and his mother was also convicted of not paying due rates in the same year. As locals, the use of aliases was not open to the Fynn family (they had crossed the paths of Crewe policemen and magistrates too often for that) and their offending careers can be traced over many years. It is also possible to collate information about the family from the ten-year censuses of Crewe. For example, we know that the Fynns were part of an established extended family residing in Peter Street, Crewe ; James was an Irishman from Mayo Lake Hill, his wife was Welsh, as was the oldest child, and the other children were born in Crewe. James worked in the iron works and had probably been attracted to Crewe by the employment possibilities created by the new railway industry which so radically transformed the South Cheshire countryside.

Crewe : the railway town par excellence

Celebrating the remarkable history of its town in 1887, the Crewe Guardian placed the birth of Crewe in the year 1837. At 8.35 a.m. on 4th July 1837 the first train passed through the Crewe Station headed for Birmingham on the Grand Junction line and this marked the beginning of the history of Crewe. A few years later in 1843, the opening of the Grand Junction Railway’s works at Crewe signalled the beginning of the town’s rapid growth. From this date onwards the expansion of the town was extraordinary. Within a generation of its opening the Crewe railway works emerged as « the most advanced railway and locomotive workshops in the world »8, as well as « the most steadily productive of all the railway companies works »9. Whilst according to one nineteenth century contemporary, Crewe became « the most important station on the London and North Western Railway »10. What is more the town’s population increased at a phenomenal rate within a few years, and continued to do so for much of the second half of the century.

Prior to the late 1830s Crewe was an old township in the parish of Barthomley, a parish located mainly around Crewe Hall, home to the Crewe family. When in 1837 a station was built here it naturally took the name of the township ; however, the new town of Crewe, which emerged during the 1840s, was located in the neighbouring township of Monks Coppenhall. Thus until 1892 the boundaries of the municipal borough of Crewe were those of Monks Coppenhall11. This fact encouraged the Crewe Guardian to note that « The place which is Crewe is not Crewe ; and the place which is not Crewe is Crewe »12. For convenience the town of Crewe took its name from its station rather than its immediate locality. However, the station of Crewe remained outside of the boundaries of the town until 193613.

The townships of Monks Coppenhall and Church Coppenhall were two divisions of the old parish of Coppenhall. Before the 1840s Monks Coppenhall was little more than a small hamlet comprising of a few dispersed labourers cottages and farms. The 1831 census, for instance, illustrated that Monks Coppenhall included twenty seven dwellings, housing the same number of families and a total population of 148 individuals (81 males and 67 females). The pattern of work was overwhelmingly agricultural with twenty-two of the twenty-seven families employed in agriculture, and the remainder working in trade and manufacture14. Ten years later in 1841 the situation had changed little : the area remained insignificant, whilst the population of Monks Coppenhall had increased by only 55 to 20315. However, by the end of 1842 the population of Monks Coppenhall/Crewe had reached approximately 1,000 and in the proceeding years it expanded at an unprecedented rate.

Fuelling this growth was the decision of the directors of the Grand Junction railway (GJR) to base its engine sheds and repair workshops to Crewe. Until 1843 the locomotive, carriage and wagon works of the company had been based at Edgehill, Liverpool. However, there were a number of problems with the site. Reed, for example, has noted that the works were located on land not owned, only rented, by the GJR ; and moreover, the site was fifteen miles from the nearest point of the GJR line (at Newton Junction). In comparison Crewe offered many advantages, not least of which was its position « near the geographical centre of the GJR system »16. The decision to move the Edgehill works to Crewe was made in June 1840. Land was subsequently purchased, and new cottages constructed to house the workforce, and in 1843 the works was officially transferred to Crewe. In March of that year eight hundred men and their families moved from Edgehill, near Liverpool17.

Crewe expanded rapidly after the introduction of the works. By the end of 1843 the population of Crewe was close to 2,000 of which 1,150 were dependent on the railway and lived in 250 railway houses. Between 1843 and 1848 the population of Crewe grew by two hundred per cent to reach a figure of 8,000. Whilst a national economic depression during the late 1840s affected the development of the town and the works, by the early 1850s an upturn in the economy encouraged further growth and expansion. Thus, by 1851 (8 years after the development of the works), its population had grown by two thousand per cent to roughly 4,500. As a result of expansion at the works, the period 1851-61 saw the population increase by seventy six per cent, the figure reaching 8,801 in 1861. The importance of the works to the fortunes of the town can be seen by the fact that in 1861 the LNWR Company employed 59.4 % of all heads of households at Crewe18. The works expanded yet further during the next decade. Between 1861-71 the company opened a steel works (1864), and also decided to centre all LNWR locomotive construction and repair at its Crewe site. In consequence the number of men employed at Crewe works increased to 3,66519. Five years later, in 1876, the year in which the town celebrated the construction of its 2,000th engine, the Crewe Guardian put the figure at 5,951 men with a further 6,762 men employed at the out-stations, making a total of 12,713.

The recruitment of more men and their families from outside of South Cheshire led to an even sharper increase in the population of the town during this decade. From 1861-71 the population of Crewe increased by 126 %, reaching 19,904 in 1871, with Crewe works having developed into a huge production facility located at three sites in the town, and employing men in a variety of different industrial processes. By 1887 the works took up 116 acres of space, with over 37 acres of roofed workshops. Population growth rates continued to remain high throughout the century expanding to 24,385 in 1881, and to 32,926 by 189120.

By 1901 Crewe housed more than 42,000 residents, 7,471 of whom were employed in the works. Whilst the rate of population growth slowed down into the twentieth century some growth was, nevertheless, noticeable. Between 1901-11 the population of Crewe rose to just under 45,000. According to Drummond, this decline in the growth rate of the town was a result of the failing health of Crewe works, and was a reflection of the town’s reliance upon its railway industry. She states, for instance, that from the late 1880s onwards the works was overstaffed and large numbers of dismissals were made at various times. In 1911, for example, five hundred men were dismissed from the works21.

Nevertheless, as Reed noted, « the great Crewe works and town, grew and grew until through many years of the 20th century the works employed 7,000 to 8,000 men and boys and the town housed over 45,000 persons, who until around 1940 were nearly all dependent on the railway for their subsistence »22. Certainly well into the twentieth century the works employed a significant proportion of the town’s population. Chaloner, for instance, notes that by 1920 the works employed slightly more than 10,000 men and boys23. The upsurge in employment opportunities over such a relatively short period of time has offered researchers the possibility of analysing the impact of massive shifts in employment on a particular region, and particularly its impact in curbing criminal offending amongst the local population.

The role of employment in desistence from criminal offending

Modern criminological research has investigated the links between gaining employment and desisting from criminal offending. Uggen and Kruttschnitt24 for example, have provided evidence that desistance is associated with gaining employment, although the precise causal links between engaging in legitimate employment and desistance from offending have yet to be satisfactorily established. Mischkowitz25 reported that « erratic work patterns were substituted by more stable and reliable behaviour » amongst his sample of desisters. Meisenhelder26 noted that the acquisition of a good job provided the men in his sample with important social and economic resources, whilst Shover27 reported how a job generated « […] a pattern of routine activities – a daily agenda – which conflicted with and left little time for the daily activities associated with crime ».

Similar sentiments were expressed by Sampson and Laub28 when they wrote that desisters were characterised as having « […] good work habits and were frequently described as “hard workers” ». Farrington et al29 reporting on the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development, wrote that « proportionally more crimes were committed by […] youths during periods of unemployment than during periods of employment », a finding supported by the later work of Horney et al30. More recently, Farrall31 found that gaining employment (along with the establishment of a sexual relationship and the adoption of a « stable lifestyle ») were the driving forces which lay behind desistance for his sample of two hundred probationers.

Why should employment be so strongly associated with desistance ? As well as being amongst the most common indicators of « adulthood » – along with parenthood – (Graham and Bowling32 and Hogan and Astone33), and hence of « maturity » and « responsibility », the acquisition of stable employment has the potential to achieve a number of things which one might expect to be associated with desistance. These include all of the following a reduction in « unstructured » time and an increase in structured’ time ; an income, which enables « home-leaving » and the establishment of « significant » relationships ; a « legitimate » identity ; an increase in self-esteem ; use of an individual’s energies ; financial security ; daily interaction with non-offenders ; for men in particular, a reduction in the time spent in single sex, peer-aged groups ; the means by which an individual may meet their future partner ; and ambition and goals, such as promotion at work34.

Some, however, have failed to find evidence to support the employment-desistance nexus. As researchers such as Ditton35 and Henry36 have shown, full time employment does not preclude either the opportunities to offend nor actual offending. Graham and Bowling37 found that for young males employment was not related to desistance, as did Rand38 when she investigated the impact of vocational training on criminal careers.

However, at least some of these negative findings can be reassessed following the findings of Uggen39 and Ouimet and Le Blanc40 (1996), which suggest that the impact of various life events upon an individual’s offending is age-graded. For example, Uggen41 suggests that work appears to be a turning point in the criminal careers of those offenders aged over 26, whilst it has a marginal effect on the offending of younger offenders. When findings like these are taken into consideration, the importance of structuring the enquiry by age is made apparent. Many of the earlier studies concerning the factors associated with desistance were, however, unaware of this important caveat and as such their findings that there was no impact of employment on desistance must be treated accordingly42.

In summary, the desistance literature has pointed to a range of factors associated with the ending of active involvement in offending. Most of these factors are related to acquiring « something » (most commonly employment, a life partner or a family) which the desister values in some way and which initiates a re-evaluation of his or her life, and for some a sense of who they « are ». Others have pointed to the criminal justice system (in most cases, imprisonment) as eventually exerting an influence on those repeatedly incarcerated.

Like any body of literature, the published studies of desistance suffer from certain biases and omissions, not least of all their geographical concentration. Virtually all of the studies on desistance have been conducted in either the United Kingdom or North American (in particular the USA). There have been some studies conducted outside of these areas – Mischkowitz’s43 study was based in Germany, Leibrich’s44 study in New Zealand and Chylicki’s45 in Sweden – but it remains the case that the bedrock of our knowledge about desistance has come from two geographical regions. This is not to say that these findings would not hold in other regions (Mischkowitz, Leibrich and Chylicki did not suggest anything remarkably different from the main literature), but rather that findings have to be « translated » with care. Societies which place less emphasis on employment or family relationships as indicators of « success » may accordingly have different processes of desistance. White collar offenders are another neglected topic in the desistance literature. Most, if not all, of the research conducted so far has focussed upon desistance from street crimes (robbery, violence, drug dealing), acquisitive crimes (burglary, theft and handling stolen property) or petty crimes (underage drinking, cannabis use or fighting). The crimes of the powerful, once again, appear to have been omitted from the research agenda. Another group of offenders that has not been the subject of exhaustive investigation is sex offenders. Possibly the closest we get to a study of the processes of desistance by sex offenders is that by Acklerley et al46 and even this is based entirely upon officially recorded data (which fails to tap undetected offending). Most of the literature related to sex offenders details the various intervention programmes run by probation services and prisons.

What has not yet been accomplished is a longitudinal study over a period where profound changes in employment levels could significantly affect crime levels within a locality ; neither has there been a study pitched at a level where the offending trajectories of individual prolific offenders can be traced over a significant period of time. We have attempted to devise such a study, and the following section describes the contours of the project, and the results of a pilot study.

The desistence project and the findings of the pilot study

The construction of a sample of prolific offenders has not been straightforward. We have thus far collected data from the Crewe petty sessions court registers for 1881, 1887, 1895, 1897, 1899, and 1911 from our original target of a sixty-year period (1880-1940). The court registers record basic details of the cases, including the names of the complainant and the defendant, the offence charged, the penalties imposed and the name of the adjudicating magistrates. We have used this data to calculate rates of crime in Crewe for those years (and therefore roughly indicate trends in violent, property and other categories of crime), which can be matched against rates of employment. This will enable an analysis of how far employment growth or decline correlates against criminal offending. This is a very crude form of measurement, however. We hope to refine a measurement of the potential of employment to assist desistence from crime by studying the effect at individual level. We have therefore identified a sub-set of repeat offenders in 1881, and traced them in other contemporary records (any offenders who committed indictable offences, and were therefore sent to quarter sessions courts, were subsequently traced in the « Cheshire Calendar of prisoners at Quarter Sessions », where their known antecedent history was recorded). Although it has not been possible to do this for the pilot study, in the main project, all of the offenders identified in the census as being employed by the railway (or related industries) will be traced in staff records of those companies. The interlinked data sets will therefore relate in the following way (see Fig 1) :

Fig 1 Data sets constructed for the project

| Petty Sessions, 1880-1940 Repeat offenders | Quarter Sessions Serious offenders sent to QS from PS Details of past offences given and also known aliases | |

| Censuses 1881-1901 Repeat offenders who reside in Crewe | Railway Staff Records, 1880-1940 Details of work career of repeat offenders |

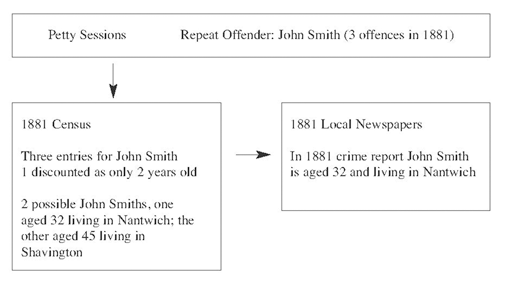

In order to ascertain that we can ensure that each offence recorded throughout the year against one person was actually the same individual we have cross-matched three types of record in the following way (see fig 2).

Fig 2 Identification process : Example of John Smith

Once this process has been completed and all repeat offenders who are resident in Crewe have been identified, traced in the census, and subsequently in railway company records, we expect to have a considerable amount of data on offenders, their families, and the work/offending careers of their offspring over a sixty year period. The results of the pilot study suggest that this database will be considerable, and complex (see Fig 3).

Fig 3 1881 statistics, and final sample numbers

| 1881 | 1880-1940* | |

| No. of offences | 455 | 27,300 |

| No. of offenders only charged with one crime in 1881 | 172 | 10,320 |

| No. of offences committed by repeat offenders | 283 (ie. 62.2 % of all offences) | 16,980 |

| Repeat offenders | 65 (4.35 offences per person) | 3,900 |

| Non-resident repeat offenders | 10 | 600 |

| Crewe repeat offenders (traceable) | 40 | 2,400 |

* Estimates based on 1881 statistics, these figures do not take account of the growth in crime during the 1880-1940 period.

In 1881 there were 65 recidivists and 172 apparent non-recidivists, which means that 37.8 % of those charged with criminal offences in 1881 were repeat offenders. Remarkable in itself, that figure can only rise once the full data set has been constructed since those offenders who were charged in 1881, 1882 and 1883 would not present as repeat offenders in our pilot study. Indeed the proportion of recidivists in the final sample could rise to the 70 % or 80 % mark, and, if that is the case, the theories of hard core criminal classes must be widely off the mark47. Given both the rise in crime, and the increase in the percentage of recidivists in the sample once all the data has been collected, we estimate that we will have a data-base comprising of approximately 2,400 – 6,000 prolific offenders active over the 1880-1940 period.

We expect to be able to identify a significant proportion of them in the Railway Works records, which will allow us to match their offending trajectories against their work careers. This will allow us to investigate key questions in criminology – does employment assists the reformation of prolific offenders ; is it the quality of the post, and successfulness of work careers that has the most influence ; does offending continues in different forms – ie. workplace appropriation ; what happens when employment ends for one reason or another – are offending identities resumed48 ; what are the long-term impacts of a person being employed on his children and grandchildren.

We are making tentative steps at this stage, but the findings of the pilot study indicate that many of the questions we pose concerning the effect of employment on desistence are answerable with the research format we have adopted, and that the results may dramatically overhaul contemporary thinking about recidivism in the late nineteenthand early twentieth-centuries.

____________

1 The authors are grateful for the comments of participants at the International Association for the History of Crime and Criminal Justice colloquium, Recidivism and recidivists : from the Renaissance to the Twentieth Century, Geneva, 6-8th June, 2002 where an earlier version of this article was presented. All authors contributed equally to this paper and are listed in accordance with British Sociology Association guidelines.

2 In the working-class districts, peoples’ belief in a criminal class may not have not been so strong, but their views were less documented, see B. Godfrey, The Rough : Conceptions of marginal criminality in the Victorian period, unpublished.

3 See summary of this research in C. Emsley, Crime and Society in England, 1750-1900, London, 1996, pp. 168-178.

4 The garrotting panic, for example, see R. Sindall, Street violence in the nineteenth-century : Media panic or real danger, Leicester, 1990.

5 See C. Beavan, Fingerprints. Murder and the race to uncover the science of identity, London, 2001 ; S. Cole, Suspect Identities. A history of fingerprinting and criminal identification, Harvard, 2001 ; and R. Ireland, « The Felon and the Angel-Copier : Criminal identity and the promise of photography in Victorian England and Wales », Policing and War in Europe : Criminal Justice History, N° 16, 2002, pp. 53-87.

6 Which have been used effectively by B. Morrison in her forthcoming Ph. D study’, « A National Shame », A history of female drunkenness in England, 1870-1914’, Keele University.

7 The Prevention of Crimes Act 1871, 34 & 35 Vict. Ch. 112 made provision only for offenders who had committed two indictable offences.

8 D. K. Drummond, Crewe : Railway Town, Company and People 1840-1914, Aldershot, 1995, p. 1.

9 J. Simmons, The Railway in Town and Country 1830-1914, Newton Abbot, 1986, p. 126.

10 F. Head, Stokers and Pokers ; or, the London and North-Western Railway, The Electric Telegraph, and the Railway Clearing House, London, 1849, p. 100.

11 W. Chaloner, The Social and Economic Development of Crewe 1780-1923, Manchester, 1973, p. 5.

12 « The Jubilee of Crewe : Containing a brief history of the rise and progress of the borough from 1837 to 1887 », Crewe Guardian, 1887.

13 B. Reed, Crewe Locomotive Works and its Men, Newton Abbot, 1982, p. 10.

14 « Jubilee », op. cit., pp. 8-10.

15 W. Chaloner, The Social and Economic Development of Crewe, op. cit., p. 8.

16 B. Reed, Crewe Locomotive Works, op. cit., p. 8.

17 J. Simmons, Railway, op. cit., p. 173.

18 D. K. Drummond, Crewe : Railway Town, op. cit., pp. 11-12.

19 Ibid., p. 226.

20 Ibid., p.13.

21 Ibid.

22 B. Reed, Crewe Locomotive Works, op. cit., pp. 8-9.

23 W. Chaloner, The Social and Economic Development of Crewe, op. cit.

24 C. Uggen, K. Kruttschnitt, « Crime in the Breaking : Gender Differences in Desistance », Law and Society Review, N° 32, 2, 1998, p. 356.

25 R. Mischkowitz, « Desistance From A Delinquent Way of Life ? », in E. G. M. Weitekamp, and H. J. Kerner (eds), Cross-National Longitudinal Research on Human Development and Criminal Behaviour, Kluwer, 1994, p. 313.

26 T. Meisenhelder, « An Exploratory Study of Exiting From Criminal Careers », Criminology, N° 15, 3, 1977, pp. 319-334.

27 N. Shover, « The Later Stages Of Ordinary Property Offender Careers », Social Problems, N° 31, 2, 1983, p. 214.

28 R. J. Sampson, J. H. Laub, Crime In The Making : Pathways and Turning Points Through Life, London, 1993, pp. 220-222.

29 D. P. Farrington, B. Gallagher, L. Morley, R. J. St. Ledger, D. J. West, « Unemployment, School Leaving and Crime », British Journal of Criminology, N° 26, 4, 1986, p. 351.

30 J. Horney, D. W. Osgood, I. Haen Marshall, « Criminal Careers in The Short Term Intra-Individual Variability in Crime and Its Relation to Local Life Circumstances », American Sociological Review, N° 60, 1995, pp. 655-673.

31 S. Farrall, Rethinking What Works with Offenders : Probation, Social Context and Desistance from Crime, Cullompton, Devon, 2002.

32 J. Graham, B. Bowling, Young People And Crime, Home Office, HORS 145, London, HMSO, 1995.

33 D. P. Hogan, N. M. Astone, « The Transition to Adulthood », Annual Review of Sociology, N° 12, 1986, pp. 109-130.

34 Full time education or voluntary work may also provide many of these features.

35 J. Ditton, Part-time Crime : An Ethnography Of Fiddling And Pilferage, London, 1977.

36 S. Henry, The Hidden Economy : The Context And Control Of Borderline Crime, Oxford, 1978.

37 J. Graham, B. Bowling Young People And Crime, op. cit., p. 56, table 5.2.

38 A. Rand, « Transitional Life Events and Desistance From Delinquency and Crime », in M.E. Wolfgang, T.P. Thornberry, R.M. Figlio (eds), From Boy To Man, From Delinquency To Crime, Chicago, 1987.

39 C. Uggen, « Work as a Turning point in the Life Course of Criminals : A Duration Model of Age, Employment and Recidivism », American Sociological Review, N° 67, 2000, pp. 529-546.

40 M. Ouimet, M. Le Blanc, « The Role of Life Experiences in the Continuation of the Adult Criminal Career », Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, N° 6, 1996, pp. 73-97.

41 C. Uggen, « Work as a Turning point », op. cit., p. 542.

42 For example, some of the earliest investigations of the relationship between employment and desistance relied upon relatively young populations. For example, Rand’s sample was under 26 years old, the members of Mulvey and La Rosa’s sample were all between 15 and 20 years old with an average age of 18 (E. P. Mulvey, J. F. LaRosa, « Delinquency Cessation and Adolescent Development : Preliminary Data », American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, N° 56, 2, 1986, pp. 212-224), and more recently, Graham and Bowling’s sample were aged 17-25.

43 R. Mischkowitz, « Desistance From A Delinquent Way of Life ? », op. cit.

44 J. Leibrich, Straight To The Point : Angles On Giving Up Crime, New Zealand, 1993.

45 P. Chylicki, To Cease With Crime : Pathways out of Criminal Careers, unpublished Ph. D. thesis, Dept. of Sociology, Lund University, Sweden, 1992.

46 E. Ackerley, K. Soothill, B. Francis, « When do Sex offenders Stop Offending ? », Research Bulletin, N° 39, Home Office Research and Statistics Directorate, HMSO, London, 1998.

47 The police were likely to target known offenders, thus inflating the figure still further. This will not in itself skew our sample since we are interested in the effect of employment on recidivists. Indeed to control for police prejudice would present a false picture of the impact of employment opportunities on crime rates.

48 Professor Keith Soothill has posed the question « If an employee is dismissed from work for, say, theft, does that mean they cannot find employment in this single industry town and vacate Crewe ? » This is an interesting issue which we hope to investigate over the lifetime of the main project.