Sex crime and recidivism in a little English city (1860-1979)1

Introduction

There is a serious neglect of history in contemporary mainstream criminology. The danger is that criminology is increasingly being defined too narrowly. The desire to define criminology narrowly follows from an attempt to identify academic territory that is not already occupied by other disciplines. However, the future strength of criminology will not rest on exclusivity but by embracing and feeding off other disciplines, especially history, sociology and psychology2. This paper is an attempt to make such a contribution.

There is much current interest in sex crime. It could be argued that the recent interest has the familiar hallmarks of a moral panic, but Soothill (1993) has stressed how in Britain most decades have had some concerns about sex offending3. In the 1950s it was a rising concern about the visibility of prostitution that eventually resulted in the Street Offences Act 1959. The move towards a partial decriminalisation of homosexuality was the focus of the 1960s and the Sexual Offences Act 1967 was the outcome, allowing homosexual acts between consenting adults in private. The new wave of the women’s movement took rape as a major issue in the 1970s and, after pressure from women’s lobbies, there was some recognition of the problems of women in the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1976. While some of the focus of the 1980s was back to the visibility of prostitution with growing concern about kerb-crawling and the resulting provisions of the Sexual Offences Act 1985 enabling men to be arrested for kerb-crawling, the main concern of the 1980s was about child abuse within the family, reaching a crescendo with the Cleveland Inquiry4 into the work of some paediatricians who had diagnosed sexual abuse and of the social services who took the children into care. Over the past decade or so, some debates feeding on familiar sexual themes have rumbled on. In the early 1990s there was discussion about the possible legalisation of brothels, the question of homosexuals in the armed services, the sentencing of rape cases and more inquiries about child sex abuse within the family. However, recent concern about serial sex killings and about paedophiles in the community has switched the focus from the family to strangers. Hence, in relation to sex crime, one can see that the topic has often been in the public arena and the interest is in what attracts concern at a particular time.

Nevertheless, while there are fashions in sex crime debates, there are still some serious issues to confront. The current concern about the future danger from convicted sexual offenders is a reasonable one. Do we have sufficient safeguards ? The recent legislation in England and Wales (e.g. Sex Offenders Act, 1997) is an attempt to meet this assumed danger. In assessing the current situation, why might a focus on history be of some help ? Certainly it is useful to understand the extent to which previous generations have had to confront similar problems.

Context of the study

I want to place two strands of my own work within a more historical context. The first strand relates to sex crime and the media where I have focused on the newspaper coverage of sex crime, principally rape5. The second strand has focused on the criminal careers of sex offenders. So, for example, we took all those convicted of an indictable sex crime in 1973 – a total of 7442 offenders – and traced their criminal careers over the next twenty years6. Partly as a result of that study and some comments we have made in articles7, Brian Francis and myself have come to be regarded as critics of the recent Sex Offenders Registration Scheme in Britain. This misrepresents our position. We do believe that there should be greater surveillance of dangerous offenders, but we argue that the issue should be considered in more depth with some sound evidence. However, the evidence on which the legislation is based is comparatively sparse. So, for example, we have argued that « there seems no criminological rationale to the determination of the periods of registration »8. In brief, knowledge about the scale, nature and longevity of the threat from sexual offenders is lacking. More pertinently, are we facing a new problem or is sexual recidivism an old problem of which we are now simply more aware ? Focusing on history will help to probe such conundrums.

I decided to look at sex crime in a local area over a long time-span – 120 years – 1860-1979. Lancaster became the location of the study. Lancaster is a very old town receiving its first borough charter in 11939 – it actually became a city in May 1937 – and is known to Shakespeare’s lovers by its links to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and later its importance in the War of the Roses. Later there were local beneficiaries from Lancaster being a transit port in relation to the slave trade – not mentioned much now in polite company but that’s why there are some nice Georgian houses in Lancaster. In Victorian times it became important as a leading centre in the world for linoleum manufacture and James Williamson (or Lord Ashton as he became known after his elevation to the peerage in 1895) became one of the richest men in Europe. The Williamson memorial – which is on the Lancaster skyline and can be seen from the M6 motorway – was opened over 90 years ago in October 1909 and described by the art historian, Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, as « the grandest monument in England ». Since then, Lancaster as a manufacturing town has been in decline. The university opened in the mid 1960s but has not been enough to arrest a general decline. In fact, its importance as an assize town began to decline much earlier from the 1830s when much county business began to move to Preston. Hence, during the 120 years of the study, Lancaster has had mixed fortunes. While socially maintaining its status through much of the time, there has been a steady decline of its manufacturing base during the twentieth century.

Methodology

A search of the local newspaper, Lancaster Guardian, for all the 120 years – that is, over 6,000 editions – has been carried out to identify any mention of sex offending. This study concentrates on the sex offences adjudicated by the courts and reported in the Lancaster Guardian.

The classification was broad, so including all offences identified as indictable10 (e.g. rape, indecent assault, incest) in the Criminal Statistics : England and Wales. In addition, appropriate non-indictable offences (notably prostitution-related offences and indecent exposure) were also included. More unusually, contraventions to a local bye-law and charged as « using obscene language » were also noted. Part of the aim of including these minor offences was to try to estimate the extent to which offenders « graduated » from minor sex crime to more serious sex crime.

While broad, the classification was not all-inclusive. There will be other crimes, not classified as sexual crime in the official statistics, that may have an underlying sexual motivation but would not be included. So, for example, theft of women’s underclothes from a washing line may stem from a sexual motivation rather than being an economic crime. Similarly, murder may have a sexual component but would not be included in the present series, which is constrained by the legal category of sex crime.

The rigour of a legal category – which was the basis for classification in this study – may fail to capture fully the rich pageantry of deviant sexual behaviour. However, this procedure leaves less scope for the vagaries of interpretation. The sexual transgressions that this study focuses upon are those proscribed by law as sex crime.

Court appearances

The term « court appearances » is important, for the focus is not simply on convicted offenders. The concern in this paper is with those persons who come to the official notice of the courts on two separate occasions. Hence, the series may include someone convicted for a sex crime in say, 1893 and an acquittal for a sex crime, ten years later, in 1903.

Study period

1860 is the first year of microfilms of the Lancaster Guardian stored in the local library. Choosing 1979 as the end year not only coincided with the start of a new era in British politics – this was the year when Margaret Thatcher first became British prime minister – but also enabled the total timeframe to be divided into six periods of twenty years (see Table 1).

Table 1 Timeframe of the study

| Years | Periods |

| 1860-1879 | Mid-Victorian |

| 1880-1899 | Late-Victorian |

| 1900-1919 | Edwardian and the Great War |

| 1920-1939 | The Inter-War Years |

| 1940-1959 | Second World War and the Post-War Period |

| 1960-1979 | Increasing liberalisation of sex laws |

The numbers in the series

1791 persons have been identified as appearing on separate occasions in a court case involving a sex offence and reported in the Lancaster Guardian in the period, 1860-1979. As there can be several defendants to one charge (e.g. in a gang-rape or a charge of indecency involving two consenting males), the total number of cases will be fewer, but the present analysis focuses on persons, not cases.

Table 2 divides the series into five major categories for each of the twenty-year periods :

Table 2 No. of persons appearing in a court case involving a sexual offence and reported in the Lancaster Guardian (1860-1979)

| Type of sexual offence | 1860-1879 | 1880-1899 | 1900-1919 | 1920-1939 | 1940-1959 | 1960-1979 | TOTAL |

| Non-consensual | 97 | 141 | 106 | 103 | 148 | 153 | 748 |

| Bigamy | 27 | 23 | 22 | 49 | 83 | 3 | 207 |

| Indecent exposure/indecency | 17 | 55 | 20 | 11 | 80 | 53 | 236 |

| Prostitution-type offences | 5 | 79 | 77 | - | - | - | 161 |

| Using obscene language | 3 | 203 | 159 | 40 | 15 | 19 | 439 |

| total | 149 | 501 | 384 | 203 | 326 | 228 | 1791 |

The « serious non-consensual » category (which principally includes rape and indecent assault11) is always quite sizeable averaging between five and eight cases per year in each period, but has the highest number of persons (shaded in Table 2) in the last twenty years (1960-79).

The number of persons charged with bigamy builds up until the peak period of 1940-59 (which coincides with the Second World War and its aftermath), but then declines quite markedly. The category, « indecent exposure and indecency », covers a motley collection of activity. It is sometimes difficult to make precise judgments from newspaper reports (see section on « triangulation » below). A person reported as behaving indecently may actually have been caught in consenting homosexual activity or exhibitionism (indecent exposure with intent to insult a female). On account of the lack of detail in newspaper reports, the behaviour – which can be very different – has been grouped in one category. However, both legally and behaviourally, the activity in this category – although very annoying to innocent victims – can be adjudged as less serious than the activity which results in charges of « serious non-consensual » offences. This category also reaches a peak in 1940-59 (shaded in Table 2) prior to the liberalisation of the sex laws in the 1960s that decriminalised some forms of consenting homosexual activity in England and Wales.

Prostitution-types offences (which includes brothel-keeping as well as prostitution) peaks during the 1880-99 period and, interestingly, there are no court reports of such activity in the local newspaper since 1920 to the end of the study period. While undoubtedly there was a decline of such activity coming to official notice during the sixty years since 1920, there may also have been an editorial decision not to mention such cases in the local newspaper (see « triangulation » below).

Finally, « using obscene language » has a similar profile to « prostitution-type » offences with a similar peak in the 1880-99 period ; however, since 1920 there has been a marked decline rather than a complete absence of the reporting of this offence in the local newspaper.

Table 2 thus indicates how the reporting of different sexual offences peaks at different periods. The public nuisance offences of « prostitution » and « using obscene language » peak in the late Victorian decades (1880-99), « bigamy » and « indecent exposure and indecency » feature prominently during the Second World War and the aftermath, while the « serious non-consensual » offences seem to rise from the Second World War onwards, although there have always been a sizeable number of such cases reported (particularly in the 1880-99 period).

However, the figures displayed in Table 2 are misleading in terms of representing sexual offending in the local area of Lancaster. Lancaster was a major assize town for most of these years and many of the more serious cases will have occurred elsewhere in the county. Furthermore, in the nineteenth century (before the advent of popular national newspapers) the newspaper also served a wider function – there were some cases reported from elsewhere in the country. However, by focusing on all those offenders having two or more separate court appearances for sex offending reported in this local newspaper in the 120 years of the study, one can consider predominantly local cases involving local people. So far, 138 sexual recidivists have been identified. There will be adjustments as further refinements are made to the database (see below), but such adjustments are unlikely to shift the main arguments.

Future adjustments

Every research study has its limitations. On the one hand, there are problems intrinsic to a research design that may not be retrievable while, on the other hand, there are problems that may be retrievable with further work. This section first concentrates on the latter possibility. With further work future adjustments will take two forms – there will be additions and subtractions. The key to such refinement is « triangulation ».

By focusing, to date, exclusively on newspaper reports, what has been described elsewhere as « triangulation »12 has not taken place. « Triangulation » involves assessing the evidence from various sources, such as court records and census returns. For Lancaster the court records are seriously incomplete while census returns are not available beyond 1901. Nevertheless, they may contribute to further refinements of the database.

Since 1933, English newspapers have not been allowed to reveal the names of juvenile offenders – there are exceptions in the most serious cases, but such exceptions are rare. Hence, there are 57 juvenile offenders who have been in court for sex offences, but cannot be named in the newspapers for legal reasons. Some of these may become sexual recidivists with another court appearance for a sex offence on a later occasion. If a search of the court records reveals these names, there is thus the potential for further persons to become included as « sexual recidivists ».

Similarly, an examination of court records is likely to reveal persons charged with sexual offences who are not mentioned in local newspaper reports. There is always bias in newspaper reporting. At the local level it seems likely that the more serious sex crimes – that is, the non-consensual cases – will get a mention but reports on the more trivial, consensual activity (such as prostitution) or social nuisance offences (such as « using obscene language ») are less likely to be comprehensive.

While perusal of court records may produce some additions, other « triangulation » work may result in some subtractions, that is, offences thought to be committed by the same person may not be the case. In local areas, with a proliferation of some common local names, the dangers are evident. Even unusual names can produce confusion. In the present study « Christopher Henry Langstreth » seemed prima facie to be the same person as « Henry Langstreth », but a more careful reading of the newspaper reports soon falsified this assumption. Further evidence from other sources may challenge some other cases that are currently assumed to be « sexual recidivists ». However, such subtractions are likely to be comparatively few in number.

Some problems relate to the limitations of the research design. This means that those who appeared in court for a sexual offence before 1860 and then appeared again after 1860 will not be included as sexual recidivists. This is known as « left-hand censoring » as a result of the study starting at a certain point. Certainly the first couple of decades of the study may be affected by this, but the fact of the low number of sexual recidivists during this period is perhaps more likely to be a result of a low level of prosecutions of sexual offending prior to 1880 (see Table 2).

Similarly, the research design means that those who appeared in court for a sexual offence before 1979 and then appeared again after 1979 will also not be included as sexual recidivists. This is known as « right-hand censoring » as a result of the study ending at a certain point. This is likely to explain any apparent decline of sexual recidivists in the Lancaster area during the 1970s.

Recognising potential biases is crucial in assisting interpretation of the data. In this study using newspapers as the source, there is likely to be an underestimate of the less serious offences while the number of the more serious offences reported in the newspaper is likely to be more accurate. However, there will be exceptions – there has often be a reluctance to report incest cases owing to legal and social constraints.

The use of other sources would be likely to produce more additions than subtractions to the current total although both possibilities are there. The likelihood of additional recruits to the ranks of sexual recidivists from the juvenile sex offenders – unnamed in newspaper reports – seems fairly high, so one needs to recognise that the numbers of « official » sexual recidivists since 1933 (when the revelation of the names of juveniles in newspapers was proscribed) may well be an underestimate.

Sexual recidivists and « official » criminal careers

« Official » criminal careers are what are known to officiais. Criminals may be committing other crimes that are not identified – the notorious « dark figure » – but these will not be part of their « official » record. of the 138 sexual recidivists in the study, it is evident that the length of their « official » criminal careers (that is, the time between their first and last court appearances) can be very different.

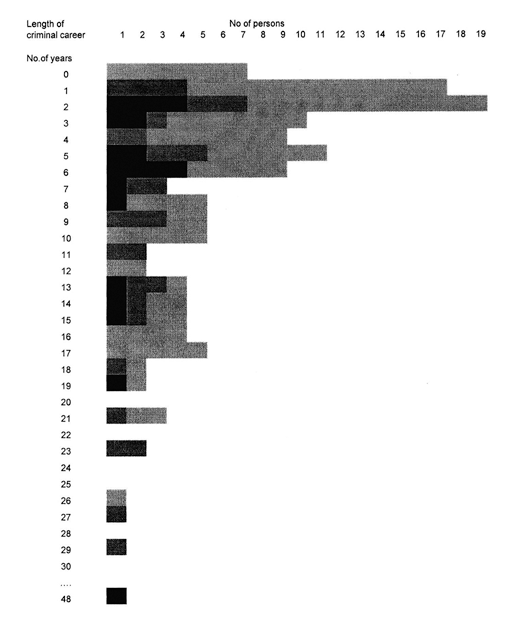

Figure 1 (annexe 1) shows how criminal careers for this series can vary between seven offenders having two court appearances for different sexual offences in the same calendar year to one offender with a criminal career spanning 48 years (1915 to 1963). The median length is around 5 years – 45 per cent of the « careers » are less than five years, while 55 per cent of the « careers » are 5 years or more. What happens to them after their last conviction or acquittal is a moot point – they could die (which is a definite desistance feature), they could genuinely quit offending, they could move to another area and continue offending where they could be apprehended (but not reported in the Lancaster Guardian), or finally, they could continue to offend in the local area and just not get caught. The possibilities are wide-ranging.

The shading in Figure 1 is important. The 19 cases highlighted in dark grey have been in court on at least two occasions for a non-consensual sexual offence. These can be regarded as the most serious « sexual recidivists ». There are a further 30 cases highlighted in medium grey who have been in court on only one occasion for a non-consensual offence and the other occasion(s) is for one of the other sexual offences – regarded in this study as not so serious. Finally, the remaining 89 cases – those shaded as light grey – are never in court for serious non-consensual offences – and probably can be regarded as social nuisances rather than a serious danger to members of the community.

Figure 1 demonstrates that there is not a clear pattern between the seriousness of a criminal career and its length. In other words, some minor sex offenders can have long « official » criminal careers as, indeed, can the more serious sexual recidivists. This has implications for monitoring sexual offenders after conviction. One certainly needs to distinguish between the length and seriousness of the criminal careers of sexual recidivists. These seem to be independent features and are thus not closely related.

Subsequent danger

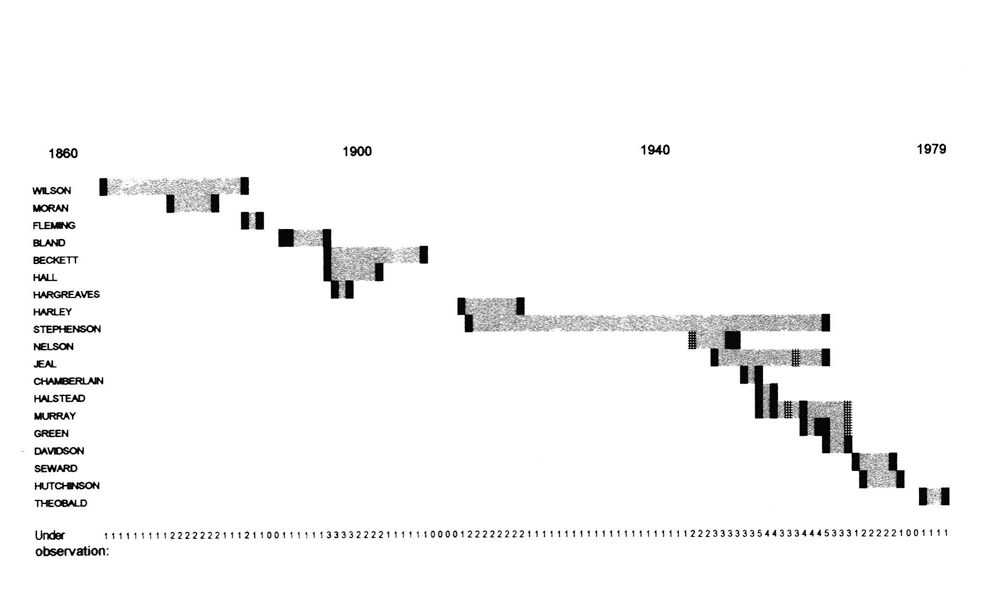

Thus, with the remarkable benefit of hindsight, one can identify 19 men who become serious sexual recidivists in the Lancaster area – that is, two court appearances for serious non-consensual offences. Are such men a comparatively recent phenomenon or are they spread fairly evenly over the 120 years ? Examining their known criminal careers over the long period of the study is informative. The black lines in Figure 2 (annexe 2) show the years in which these serious sexual recidivists appeared in court for non-consensual offences – the hatched lines relate to appearances for other kinds of sexual offences. The light grey background indicates the years between their first and last convictions for sexual offences. These are the years that – if one had had the knowledge – these offenders could usefully have been under surveillance. So, for instance, there is the offender whose criminal career spans 48 years, displayed in Figure 2 from 1915 to 1963. Most, however, have comparatively short criminal careers.

The bottom line in Figure 2 indicates the numbers who could have been usefully under observation in any one year. These consist of all those who will eventually appear in court again charged with a non-consensual sexual offence. The numbers fluctuate from five to zero in any one year. However, the crucial point to recognise is that the numbers are always comparatively few.

It is unusual for these offenders to appear in court for sexual offences other than serious non-consensual ones. There are four exceptions all of which occur since the Second World War. A brief summary of each of these « careers » helps to raise some important points. The age shown indicates the start of their « career » :

| NELSON (aged 31) | September 1945 August 1950 June 1951 December 1951 | Indecent exposure Indecent assault Indecent assault Indecent assault | 3 months imprisonment 6 months imprisonment 6 months imprisonment 6 months imprisonment |

| JEAL (aged 25) | April 1948 February 1959 July 1963 | Indecent assault Indecent exposure Indecent assault | 2 years imprisonment 6 months imprisonment Probation 2 years |

| MURRAY (aged 18) | July 1954 | Indecent assault | Probation 2 years with condition of in-patient treatment |

July 1956 March 1958 February 1960 March 1966 | Indecent assault ‘Peeping Tom’ Indecent assault ‘Peeping Tom’ | Probation 3 years Bound over for 12 months Outcome not stated Bound over for 12 months | |

| GREEN (aged 31) | October 1960 June 1961 October 1963 October 1966 | Indecent assault Indecent assault Indecent assault ‘Peeping Tom’ | 12 months imprisonment Bound over for 12 months 6 months imprisonment Bound over for 12 months |

Two of the cases (Nelson and Jeal) were convicted for « indecent exposure » (often described as exhibitionism) as well as « indecent assault », while the other two cases (Murray and Green) were also convicted of « Peeping Tom » offences. « Peeping Tom » is a colloquial description used in newspapers for spying on the occupants of a house usually through the bathroom or bedroom windows (and likely to be charged as « conduct likely to cause a breach of the peace »). The fact that there were no such cases prior to the Second World War raises two possibilities – either sexual offenders are becoming more versatile (suggesting a change of behaviour) or social control agents and perhaps the public are becoming more vigilant (suggesting a change in the social control of sexual offenders). In fact, these possibilities are not mutually exclusive but they are at the heart of considering changes over time. If there are apparent changes, then is this the result of a change in sexual offending or a shift in social control procedures ?

So, with the benefit of hindsight, this study identifies the number of « official » serious sexual recidivists there were around in Lancaster and its environs during these 120 years. Up to the end of the Second World War, there were about one or two a year who could have been usefully under observation although there were three at some points at the start of the twentieth century. After the Second World War, the number of sexual recidivists began to rise and later, with the addition of those outside the scope of the study (that is, appearing in court for a sexual offence before 1979 and then recidivating after the end-point of the study), one can recognise that the numbers appropriate for surveillance seems to continue to increase.

However, the present study does not produce definitive evidence that there have, indeed, been changes. Studies based on newspaper reports are open to challenge and there has been no account of changes in population over time. Nevertheless, even if all possible sources had been searched – completing the « triangulation » that appeals to Godfrey and Farrall13 – there will still be a shortfall owing to the « dark figure ».

While this account usefully illustrates the scale of the problem when what is eventually known « officially » is analysed, such an analysis would be incomplete without further mention of the « dark figure » of sexual recidivism. Any fluctuations in the figures may reflect fluctuations in the mysterious « dark figure ».

The « dark figure » of sexual recidivism

Speculating on the « dark figure » of crime means that one oscillates between the « unknown » and the « unknowable ». For the period between 1860 and 1979 the actual amount of sexual offending is both unknown and unknowable. The « unknown » includes information that could have been known but is not, while the « unknowable » identifies information that is not possible to know. The « unknowable » is not an absolute category so, for example, before the age of space travel, what was on the other side of the moon was thought to be « unknowable », but this is now known.

Identifying the actual amount of sexual offending is always problematic. One can speculate that, in an earlier era, less sexual crime is likely to have been disclosed to the authorities as shame and embarrassment was previously a much greater component of the victim’s experience but the overall effect of this is difficult to assess. Nowadays, victim surveys (such as the British Crime Survey) provide some clues of the amount of « hidden crime ». However, assessing the amount of crime is different from assessing the number of offenders. From victim surveys in an area one can perhaps discover that there are 100 unreported rapes, but the number of those rapes which are committed by one person or by different persons is less easy to conclude. While the value of offender surveys – as supplementing victim surveys – has recently been posited, few people are likely to admit to rapes that have not been reported. Hence, the actual number of sexual offenders in any age is perhaps closer to the « unknowable » than simply being « unknown ». If this argument is accepted, then the implication seems to be that one really knows as much about sex offenders in the past as one does about sex offenders in the present.

This is a bold claim that encourages the greater use of history to examine patterns and processes. The advantage of history is that patterns over long trajectories can be explored, while the present only reveals the potential to be explored in the future. So what can one usefully learn from this study about sexual recidivists in the 120 years of Lancaster history ?

Conclusions

It is tempting to be extravagant in one’s claims but this is only a modest study with limitations that have already been outlined. However, it is a novel approach that draws together the interests of criminologists and historians. Hence, as a demonstration project, it has been successful ; it shows how one can probe the extent to which contemporary problems have arisen in the past. Furthermore, there are some lessons to be learned, or at least confronted.

This study has focused on those persons who appear in court on two or more occasions charged with a sexual offence and reported in the local newspaper, Lancaster Guardian. Of the 138 persons so identified, it is argued that 19 (or 14 %) appear for serious sexual offences on two or more occasions, while a further 30 (or 22 %) appear for a serious sexual offence on just one occasion. Of the remaining two/thirds (or 64 %), they will be engaged in less serious, albeit often annoying and distressing, activity. Much of this latter behaviour will reflect either the moral values or behaviour of a particular era – concern about overt prostitution and obscene language in the late Victorian period, increasing persecution and prosecution of homosexuals up to the liberalising Act of the late 1960s.

This finding usefully reminds of the dangers of what elsewhere we have described as « criminal apartheid »14. Generally sexual offending has tended to be set apart from other types of offending. The tendency to separate off sexual offending is perhaps becoming more marked. Indeed, as all sexual offending increasingly becomes regarded as abhorrent, there will be a greater tendency of those committing such offences to be segregated from offenders committing other types of offences, who will wish to distance themselves both symbolically and territorially from those so identified. This study should help to remind that not all sex offenders are really dangerous ; in fact, it will be a minority. This study suggests that there were around 19 persons who demonstrated that they continued to exhibit dangerous behaviour. However, there were many more who committed unpleasant and possibly dangerous acts on just one occasion.

This study is of no assistance in helping to identify the dangerous minority who commit serious sexual offences on one or more occasions. It simply indicates the scale of the problem of those who come to official notice on more than one occasion. Even with the benefit of hindsight, the numbers of serious sexual recidivists remain small in a local area. However, there is some suggestion that these small numbers have been increasing since the Second World War. While some of this increase may be accounted for by population increases and increased mobility (predators moving in and out of certain localities), the fundamental issue is whether there has been any change in offending behaviour (that is, whether more males become engaged in serious sexual offending) or whether there has been any change in surveillance (that is, members of the public being more willing to report incidents and the police taking such reports more seriously).

The present study cannot resolve this conundrum. Certainly further work may produce some clues. For example, if newspaper reports suggest that offenders have fewer offences to be « taken into consideration » (that is, other offences they are willing to admit to), then this may inidicate they are being caught more quickly – or, alternatively, that offenders are becoming more sophisticated in terms of what they might admit to ! Similarly, if offenders are caught at a younger age, this may mean that they are being caught earlier – or that they are starting their offending earlier. The permutations are endless. The importance of « triangulation » – that is, getting evidence from various sources – cannot be overestimated. However, what this demonstration study has, hopefully, demonstrated is that the pathways of historians and criminologists can usefully overlap.

Figure 1 Lengths of “official” criminal careers of 138 sexual recidivists

Figure 2 The criminal careers of those with two or more court appearances for serious non-consensual offences

____________

1 I wish to thank the Nuffield Foundation for the grant for part of the work on this project and to Emma Robinson and Hannah Yates for their assistance.

2 K. Soothill, M. Peelo, C. Taylor, Making Sense of Criminology, Cambridge, chapter 8, « Criminology in a Changing World », 2002.

3 K. Soothill, « The serial killer industry », The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, vol. 4, N° 2, September, 1993, pp. 341-354.

4 E. Butler-Sloss, The Cleveland Report, London, HMSO, 1988.

5 K. Soothill, S. Walby, Sex Crime in the News, London, 1991 ; K. Soothill, C. Grover, « The public portrayal of rape sentencing : What the public learns of rape sentencing from newspapers », Criminal Law Review, July, 1998, pp. 455-464.

6 K. Soothill, B. Francis, B. Sanderson, E. Ackerley, « Sex Offenders : Specialists, Generalists – or Both », British Journal of Criminology, vol. 40, 2000, pp. 56-67.

7 K. Soothill, B. Francis, « Sexual reconvictions and the Sex Offenders Act 1997 », New Law Journal, vol. 147, N° 6806, (5 September), pp. 1285-1286 and vol. 147, N° 6807 (12 September), 1997, pp. 1324-1325.

8 Ibid., p. 1325.

9 A. White (ed.), A History of Lancaster, 1193-1993, Keele, 1993.

10 While the Criminal Statistics : England And Wales separate into « indictable » and « non-indictable » offences, the distinction is largely obsolete. Furthermore, the dividing line changes from time to time. There are certain crimes which may only be tried upon indictment, but there is a large number of indictable offences which may, in certain circumstances, be tried summarily. Conversely, there are certain summary offences which may, if the accused so wishes, be tried upon indictment.

11 Incest was also included as « non-consensual » but sibling incest may be « consensual ». However, newspaper reports on incest – which are quite rare – may fail to clarify this.

12 See in this volume B. Godfrey, S. Farrall, John Locker, « Persistence in crime and the impact of significant life-changes : a pilot Study of Crewe, 1881 ».

13 Ibid.

14 K. Soothill, B. Francis, « Sexual reconvictions and the Sex Offenders Act 1997 », op. cit.