Neither Naxian nor Parian

On some Eretrian vases of the 8th and 7th-cent. BC found on Delos and Rheneia

Preamble

Dear André,

It is in Eretria on the island of Euboea that we met for the first time – you were preparing a study on Euboean reflections in Mycenaean linear B-texts, which appeared a few years later in the 5th volume of the Eretria. Fouilles et recherches series1, whilst I was trying to establish the chronology of the pre-Classical West Gate on the basis of the very fragmentary pottery finds2, an endeavour that was to be published in the same volume as yours3. Those days marked the start of a long-lasting friendship, and so I thought some vases made in Eretria in the Archaic period and brought to Delos may be an appropriate offering on this festive occasion.

Introduction

Euboean, and often specifically Eretrian, pottery of the 8th century bc, especially of its second half, has been found in numerous sites throughout the Mediterranean, but these exports decrease quite dramatically from the start of the 7th century to cease altogether by its third quarter. Hardly any identifiable Eretrian, or more generally Euboean, pottery datable between c.650 and c.560 bc has been found outside Euboea.

This paper aims at presenting the only major exception4, the Eretrian pottery found on Delos and Rheneia. Apart from a few hitherto unpublished pieces, the vases in question have been presented by Charles Dugas and Constantin Rhomaios in the Exploration archéologique de Délos series, of which the 10th fascicule, published in 1928, includes the pottery from the Heraeum, whilst the 15th and 17th, which came out in 1934 and 1935 respectively, contain the pottery from the so-called Purification Trench on Rheneia. Discovered and excavated in 1898 by D. Stavropoullos, it was filled with the funerary offerings from the tombs that had been removed from Delos by the Athenians in 425 bc, as Thucydides records5. Whilst the finds from Rheneia are kept in the Archaeological Museum of Mykonos, the Delian vases have remained on Delos6.

The Geometric period

The first Eretrian vases may have arrived on Delos as early as the first half of the 8th century, as some of the pendent semi-circle skyphoi from Rheneia are likely to be of Eretrian manufacture7, and during the second half of the century there seems to have been a steady trickle of imports: to the pieces discussed on previous occasions8 the following can be added, in roughly chronological order.

1. Mykonos 1146: amphora (fig. 1).

Ht. 40.8, diam. mouth 15.0, diam foot (reconstr.) 10.0 cm.

Clay reddish-yellow (5-6YR 6 / 5), well-levigated, very hard fired, without mica. Yellow-brownish slip (2.5Y 7 / 3-10YR 7 / 4); black, slightly brilliant paint, brown-reddish (5YR 3 / 4) where diluted; added white (2.5Y 8 / 3).

Bibl.: Délos XV 75 Bb 10 pl. 36.

Dugas and Rhomaios placed this amphora, together with some 50 other vessels of various shapes, in their Bb Group. On the basis of its very narrow distribution – at the time Délos XV was published, all representatives of the group had been found on Naxos or on Delos-Rheneia – they thought its place of manufacture to be either on one of the two, or else on an island nearby. The pottery that has come to light on Naxos in the last few decades has revealed that the group is, on the whole, of Naxian manufacture9. The feature that is common to all its members is the presence of a yellowish slip which covers the vase’s entire surface. Furthermore, most vessels are made of an orange-reddish clay that contains a fair amount of mica. Our vessel is one of the rare exceptions: its clay is practically free of mica, which is usual for Euboean and for Eretrian pottery in particular10. Furthermore, it is the only piece the decoration of which includes motifs painted in added white on top of the blackish paint. Dugas and Rhomaios interpreted this feature as a chronological marker and suggested that our amphora might be of a somewhat later date than its companions of the Bb Group, emphasizing at the same time that its shape prevented it from being separated from the rest of the group.

Today, we know that the addition of motifs, especially but not exclusively, wavy and zig-zag lines, painted in white on top of black bands or zones are among the hallmarks of Eretrian (and Lefkandian) Late Geometric pottery11. They are particularly popular on large vessels, both open and closed12, and several fragments that come from amphorae similar to the one in Mykonos, among them inv. V 3292 (fig. 2), have been found in Eretria in a pit filled with MGII-LG pottery beneath a 4th-cent. bc building south of the West Gate, known as “Edifice III”13.

2. Delos 1931: kantharos (fig. 3)

Ht. 14.5 cm.

The fabric is very close to that of the previous vase, but clay and slip are slightly more brownish (5YR 5.5 / 4 and 10YR 6.5 / 3 respectively). The black paint is matt except for some metallic spots, dark greyishbrown when diluted.

Bibl.: Délos XV 65 Ae 84 pl. 32A; Coldstream 1968, 50, 179 pl. 38e.

The kantharos, part of Dugas’ Ae Group, has more recently been considered to be of Cycladic (‘Parian’) manufacture14, but the absence of mica in the clay and the rather sloppy style speak in favour of an Eretrian origin.

This hypothesis is confirmed by a rim fragment from a kotyle found in the precinct of the Temple of Apollo at Eretria (B 1024: fig. 4). The meander motif in the central metope of its handle zone is very similar to that we see on the Delian kantharos. In both cases the painter, clearly inspired by Attic models15, has not quite understood how to imbricate the meander hooks and has reduced one of them to a horizontal hatched band.

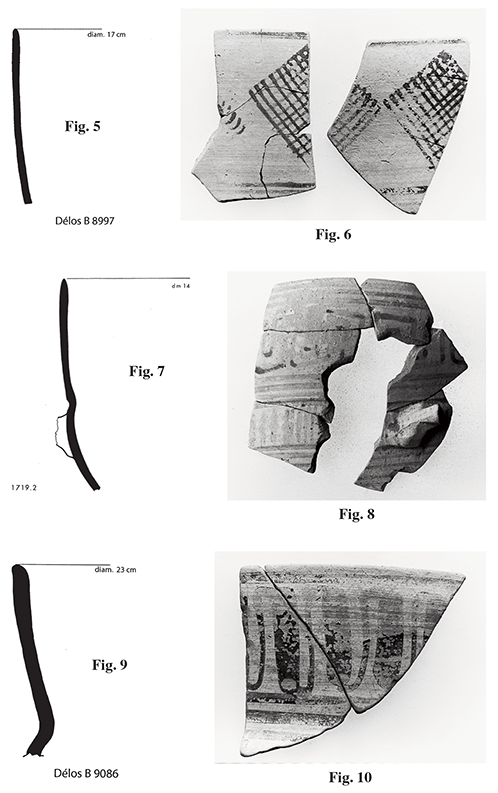

3. Delos 8997: chalice skyphos, 2 rim frgts. (figs. 5-6)

Ht. max. 6.6; l. (1) 5.5; l. (2) 4,8; diam mouth (reconstr.) 17 cm.

Very pale brown clay (10YR 7 / 3-4), well levigated and without mica. Matt black paint, brown where diluted (7.5YR 4 / 6 on the outside, 10YR 5 / 3 on the inside).

The two fragments stem from a chalice skyphos, a type of drinking vessel characterized by its size (the diameter of the mouth usually exceeds 16 cm) and above all by its very high rim (measuring more than a quarter of the mouth diameter). It appears to be a Euboean invention of the late 8th century16 and remains part of the repertoire throughout the Archaic period17.

The Delian vessel is very close to Eretria FK 1719.2 (figs. 7-8) by both shape and size. In addition, both pieces imitate Corinthian pottery by the colour and texture of their fabric as well as by their very thin walls and the linear style of their decoration. This is particularly obvious on the Eretrian skyphos, the motifs of which are clearly inspired by Early Protocorinthian models: a meander on the high rim, a metopal frieze with soldier birds in the handle zone, both framed by encircling fillets. Similarly, the lozenge chain on the Delian skyphos is an exceptionally fine example of a motif that is among the most popular on Euboean Late- and Sub-geometric vessels, where it appears in a wide range of varieties, single or multiple, cross-hatched or dotted18. Comparable to the Delian lozenges are those on three bowl-pyxides of the late 8th century, possibly of Lefkandian rather than Eretrian manufacture, only one of which stayed at home19, while the other two were found in Veii20 and Al Mina respectively21.

The 7th century

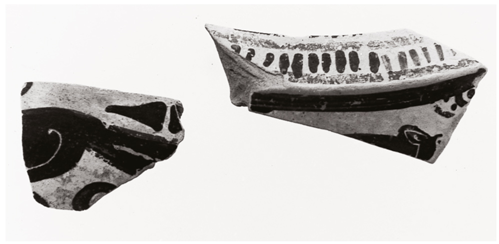

4. Delos 9086: chalice skyphos, rim frgt. (figs. 9-10)

Ht. 6.8, l. 8.3, diam mouth (reconstr.) 23 cm.

Well levigated, light red clay (2.5YR 6 / 6), not very hard fired. Fine, very pale brown slip (10YR 7.5 / 4), matt reddish-brown paint (2.5YR 4 / 4).

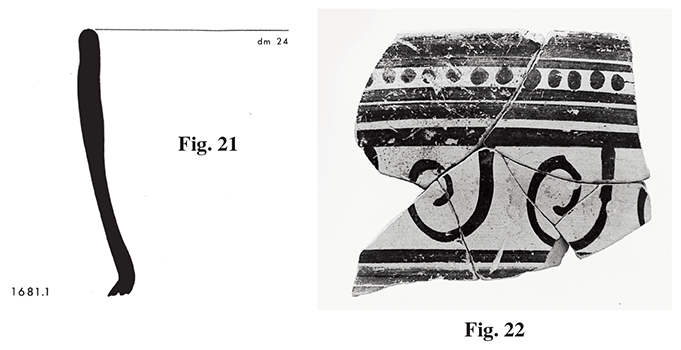

Linked elongated blobs or tongues as they feature on the rim of this chalice skyphos constitute a very popular motif on Late- and Sub-geometric Eretrian vases22 and therefore provide no clue as to the date of the vessel. Its shape, however, reveals it to be considerably later than might have been expected at first sight. It is practically identical with that of the fragment FK 1681.1 from a chalice skyphos found in the Herôon at Eretria (fig. 21) which, as we shall see below, can be dated to the last third of the 7th century.

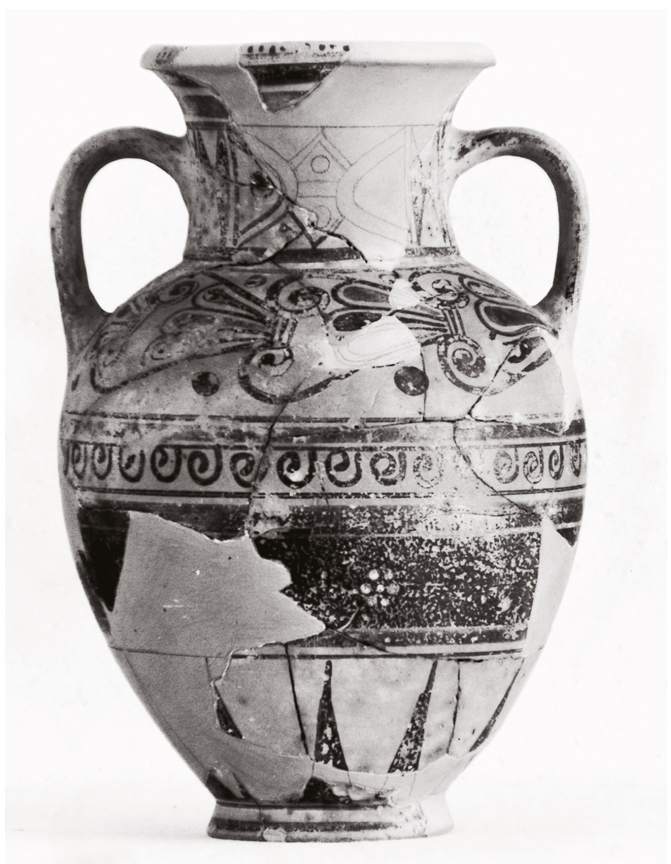

5. Mykonos 662: neck amphora (figs. 11-13)

Ht. 26.9, diam mouth 12.2, diam foot 8.4 cm.

Clay well levigated, hard fired, without mica. On the surface, which has been carefully polished, brownish-yellow (9YR 7 / 5) to brown (6YR 5 / 6). Black paint (7.5YR 3 / 1-2), brilliant in some areas, rarely diluted to a reddish-brown colour (5YR 4 / 5). Added red (1.5YR 3 / 6) and white (10YR 8 / 3).

Recomposed from numerous fragments, several lacunae replaced with plaster, as can be seen from the photographs. Surface pitted in places, paint in parts worn.

Inside reserved except for the mouth which has a large circular band above and several fillets below. The resting surface of the foot and the underside of the vessel are also reserved, while a band encircles both the outside and the inside of the foot.

On the lower part of the belly, rays between circular fillets; above, black zone with a band added in red along both its lower and upper edges. In the central part of the zone, framed by two white fillets, frieze of dot rosettes, also in added white. Around the widest diameter of the vase, frieze of hanging spirals between fillets, red band above.

On either shoulder, three horizontal palmettes, linked to each other by their lateral volutes. Each palmette is composed of three leaves which are drawn in black outline, with their core alternately black and red, applied directly on the clay surface. Large dots inbetween.

On the neck, the central panel, between large double axes, features a curious motif which Dugas describes as “deux yeux dressés verticalement, adossés et réunis par des traits horizontaux et par des angles”. On the upper part of the neck, above the handle attachments, one red followed by one black band, applied directly on clay ground. On the rim, dot frieze between fillets: black below, red above. Vertical black band on the outside of the handles, between two lines along the edges.

Bibl.: Délos XVII 24-25, 31 no. C 23 pl. 25; Buschor 1929, 146 Beil. 52: 2; Boardman 1952, 28; Kübler 1970, 368 n. 151; Descœudres 1976, 40 n. 87 pl. 6.

As Dugas already saw, the following four pieces are in every respect so similar to the one just described that their attribution to the same workshop, if not to the same potter and painter, allows of no doubt.

6. Mykonos 663: neck amphora, upper part (fig. 14)

Ht. (as pres.) 13.3, diam mouth (reconstr.) 12.8 cm.

Fabric as last, but paint very dark grey (5Y 3 / 1), rarely diluted to a reddish-yellow colour (5YR 6 / 6).

Recomposed, several lacunae replaced in plaster.

As last, but: on the shoulder, hanging rays with solid little waterbirds between the tips: on the neck, the upright fields on either side of the central panel subdivided by two pairs of horizontal lines into three, each with a dotted St Andrew’s cross.

Bibl.: Délos XVII 24-25, 31 no. C 24 pl. 25.

7. Mykonos 663a: amphora, wall fragment

Max. l. 10.0 cm.

Fabric as last.

Recomposed from five sherds.

Possibly from the same vase as last. Rays above the foot (only tip of one is preserved), then band in added red applied on a black one between black fillets. Dotted wavy line above, followed by fillets and a second red band on black paint.

Bibl.: Délos XVII 24-25, 31 no. C 27 pl. 19C.

8. Mykonos 664: neck amphora, upper part (fig. 15)

Ht. (as pres.) 13.1, diam mouth (reconstr.) 14.3 cm.

Fabric as Mykonos 662 (5). Paint, where well preserved, brilliant.

Recomposed, several lacunae replaced in plaster. Paint in places much worn.

As Mykonos 662 (5), but: on the inside of the mouth, two encircling bands; on the shoulder, four hanging spirals on either side, between encircling bands. On the neck, the central panel, as it features on Mykonos 662 and 663, is widened so as to cover the entire surface.

On the rim, broad vertical bands, widely interspaced.

Bibl.: Délos XVII 24-25, 31 no. C 25 pl. 25.

9. Mykonos 675: neck amphora, lower part (fig. 16)

Ht. (as pres.) 18.7, diam foot 8.9 cm.

Fabric as Mykonos 662 (5). Paint, where well preserved, slightly brilliant. Added red slightly darker (10R 4 / 2.5), white much faded.

Recomposed, numerous lacunae replaced in plaster.

Inside, underside, resting surface, and interior face of foot reserved.

On the exterior face of the foot, black fillet and broad band in added red, painted directly on the clay ground. Rays on the lowest part of the body, followed by a black zone. Its centre framed by a pair of white circular fillets, its lower and upper borders each with a band in added red. Above, between dot friezes framed by circular lines, frieze of hanging spirals similar to, but slightly larger than, those on Mykonos 662 (5). Below the shoulder red band painted directly on clay ground. Of the shoulder decoration itself, only a dot and a small segment of a curved band have survived, possibly belonging to a palmette frieze as on Mykonos 662 (5).

Bibl.: Délos XVII 24-25, 31 no. C 26 pl. 19C.

To these 5 pieces already assembled by Dugas, one more can be added that appears to have escaped his attention:

10. Mykonos KA 814: neck amphora, neck and mouth fragment with part of the handles (fig. 17)

Ht. (as pres.) 11.2, diam mouth (reconstr. 13.0 cm.

Fabric as Mykonos 662 (5).

Recomposed, with several gaps closed with plaster. About half the neck and the mouth preserved.

Shape and decoration as Mykonos 663 (6), but only two, instead of three, St Andrew’s crosses on top of each other in both side fields.

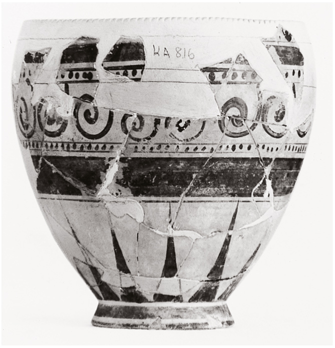

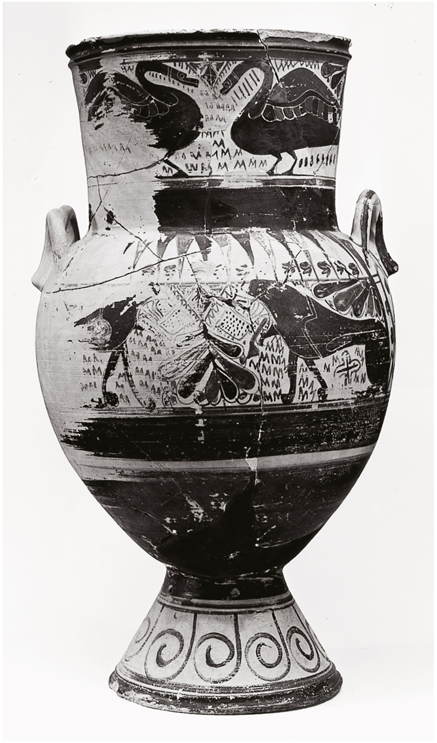

The main vase of our group, Mykonos 662 (5), was mentioned and illustrated for the first time in 1929 by E. Buschor, who held it for Parian23. At the same time, he was struck by its affinity with some of the large funerary amphorae that the excavations in Eretria’s western cemetery had brought to light between 1885 and 190024. This he explained by assuming that the vases produced on Paros had inspired the Eretrian makers of the grave amphorae – “von parischen Gefässen dieser Stufe möchte man sich die eretrischen Gefässe beeinflusst denken”. In Délos XVII, Dugas incorporated Mykonos 662 and the few pieces that go with it into his ‘Group C’. The group which he calls “Orientalisant des Cyclades”, represents for him “à côté des vases méliens ce que les ateliers des Cyclades ont créé de plus achevé”25, but he does not attempt to identify the precise location of the workshop that produced it. This was left to J. K. Brock, whose arguments in favour of a Naxian origin26 have proven more convincing than Buschor’s original proposal27. According to F. Villard, scientific clay analysis also confirms Naxos as the place of manufacture of Group C28, though he fails to state from which vase(s) samples were tested. However, it can be safely assumed that Mykonos 662 was not amongst them, nor any of the other amphorae that go with it, since they form, as Dugas notes, a distinctive sub-group. They stand out by their different fabric, “la teinte brune de la surface, la nuance marron du vernis”, but also by “un certain laisser-aller dans l’exécution” and by their decoration, which is less variegated29.

In his important paper on the “Pottery from Eretria” J. Boardman harks back to Buschor’s observation of a possible link with some of the Eretrian grave amphorae, in particular with those of his Group D that he dates to the early 6th century30. The frieze of hanging spirals that appears on the high foot of most, if not all, of them, including the particularly representative and well-preserved amphora Athens NM 12436b (fig. 18), constitutes the most obvious link with the Mykonos group, but no less noteworthy are the solid little waterbirds between the tips of the hanging rays on the shoulder. Yet, despite the similarities “in technique and motifs” which the Mykonos amphorae exhibit with the Eretrian funerary vessels, Boardman judges them to be stylistically too different to be of Eretrian manufacture. They are, he observes,“more carefully painted than any vases of this period found in Eretria”31.

In the light of the pottery found in the so-called Herôon south of the West Gate during the excavations carried out by the Swiss Archaeological School between 1965 and 1976 this judgment can no longer be upheld.

Several fragments are now known in Eretria that are in terms of both motifs and style so close to the Mykonos vases that an attribution to the same workshop seems indisputable. A small dinos fragment (FK 368.1), stemming from this “Mykonos 662 workshop”, had already been found in one of the first excavation campaigns32.

Since then, the remains of a second dinos came to light, FK 1662.2 (fig. 19), evidently from the same workshop again33. Its shoulder frieze on one side looks almost like a “cut and paste” from Mykonos 662 (5), while on the main side (fig. 20) the vessel was decorated with an animal frieze of which only parts of a dog running to the right have survived.

Its brother was luckier, as the pyxis on which it runs has survived intact: it is alleged to have been found in Corinth, no doubt in a grave, and is now in the National Museum in Athens (inv. 276)34. A large star decorates its lid, and between the tips of its rays appear again the solid little waterbirds which we have met on the shoulder of Mykonos 663 (6)35.

The frieze of hanging spirals, which represents another characteristic element of the Mykonos 662 group, is also well attested among the Heroon pottery, and several fragments exhibit the same fabric and style. The frieze on the calice-skyphos fragment FK 1681.1 (figs. 21, 22), which we have already mentioned, is particularly close to the one on Mykonos 675 (9)36.

The abundant use of added colours, especially red, on the vases of our group, but also the white dot rosettes on Mykonos 662 (fig. 11) suggest that the Eretrian potter and painter who produced them knew of Late Protocorinthian and Late Protoattic vases37. The animal friezes on the other hand, as seen on the dinos Eretria FK 1668.2 and the pyxis Athens NM 276, with the huge dog and the variegated, widely spaced filling ornaments, reflect an awareness of Early Corinthian, resp. Early Blackfigure trends. In terms of absolute chronology, a date in the last third of the 7th century bc appears therefore most likely, and this is confirmed by both Corinthian imports found in association with members of our group in the Herôon38.

Conclusion

In the wake of H. Dragendorff’s and E. Pfuhl’s attribution of a large group of vases found on Thera to Euboea39, many Late Geometric and Archaic vases from Delos and Rheneia were once thought to be of Euboean manufacture40. Practically without exception, they subsequently turned out to be either Parian or Naxian41. As far as ceramic offerings were concerned, it looked for a long time as if the Euboeans had not been among the visitors to the main Ionian sanctuary. Far from challenging the predominant role Naxos and, to a lesser extent, other islands and Paros in particular played on the sacred island, the Eretrian vases presented here witness to the existence of continuous links from the Geometric period to the end of the 7th century between Apollo’s city in Euboea and his birthplace on Delos – as one might have expected42.

Bibliographie

Andreiomenou, A. (1977) – “Γεωμετρική και υπογεωομετρική κεραμεική εξ Ερετρίας, II”, Αρχαιολογική Εϕημερίς, 127-163.

Andreiomenou, A. (1981) – “Γεωμετρική και υπογεωομετρική κεραμεική εξ Ερετρίας, III”, Αρχαιολογική Εϕημερίς, 84-113.

Andreiomenou, A. (1982) – “Γεωμετρική και υπογεωομετρική κεραμεική εξ Ερετρίας, I”, Αρχαιολογική Εϕημερίς, 161-186.

Andreiomenou, A. (1996) – “Pottery from the Workshop of Chalcis (9th to 8th Centuries BC): Large Closed Vases”, in Evely, D. et al., Minotaur and Centaur. Studies presented to Mervyn Popham, BAR Int. Ser. 638, Oxford, 111-121.

Auberson, P. and Schefold, K. (1972) – Führer durch Eretria, Bern.

Boardman, J. (1952) – “Pottery from Eretria’, Annual of the British School at Athens 47, 1-48.

Boardman, J. (1957) – “Early Euboean Pottery and History”, Annual of the British School at Athens 52, 1-29.

Brock, J. K. (1949) – “Excavations at Siphnos”, Annual of the British School at Athens 44, 1-80.

Buschor, E. (1929) – “Kykladisches”, Athenische Mitteilungen 54, 142-163.

Coldstream, N. (1968) – Greek Geometric Pottery, London.

Cook, R. M. (19973) – Greek Painted Pottery, London.

Délos X – Dugas, Ch. (1928) – Exploration archéologique de Délos, X: Les vases de l’Héraion, Paris.

Délos XV – Dugas, Ch. and Rhomaios, C. (1934) – Exploration archéologique de Délos, XV: Les vases préhelléniques et géométriques, Paris.

Délos XVII – Dugas, Ch. (1928) – Exploration archéologique de Délos, XVII: Les vases orientalisants de style non mélien, Paris.

Descœudres, J.-P. (1972) – “Un aryballe érétrien au Musée de Délos”, Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 96, 269-282.

Descœudres, J.-P. (1976) – “Die vorklassische Keramik aus dem Gebiet des Westtors”, in Eretria. Fouilles et recherches V, Bern, 13-58.

Descœudres, J.-P. (1983) – “Greek Pottery at Veii: Another Look”, Annual of the British School at Athens 78, 9-41.

Erétrie. Guide (2004) – av., Erétrie. Guide de la cité ancienne, Gollion.

Dragendorff, H. (1903) – Thera II: Theräische Gräber, Berlin.

Hurst, A. (1976) – “Ombres de l’Eubée ? (Quelques mots mycéniens)”, in Eretria. Fouilles et recherches V, Bern, 7-11.

Kahil, L. (1981) – “Erétrie à l’époque géométrique”, Annuario della Scuola archeologica di Atene 59, 165-172.

Kearsley, R. A. (1995) – “The Greek Geometric Wares from Al Mina Levels 108 and Associated Pottery”, Mediterranean Archaeology 8, 7-81.

Kearsley, R. A. (1989) – The Pendent Semi-circle Skyphos. BICS Suppl. 44, London.

Knauss, F. S. (1997) – Der lineare Inselstil, Saarbrücken.

Kourou, N. (1998) – “Euboea and Naxos: the Cesnola Style”, in Bats, M. and d’Agostino, B., Euboica. L’Eubea e la presenza euboica in Calcidica e in Occidente, Napoli, 167-177.

Kourouniotis, K. (1897) – “Ερέτρια”, Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 21-23.

Kourouniotis, K. (1898) – “Ανασκαϕαί Ερετρίας”, Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 95-99.

Kourouniotis, K. (1900) – “Ανασκαϕαί Ερετρίας”, Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 55-56.

Kourouniotis, K. (1903) – “Αγγεία Ερετρίας”, Αρχαιολογική Εϕημερίς, 1-38.

Krause, C. (1972). – Das Westtor. Eretria. Fouilles et recherches IV, Bern.

Kübler, K. (1970) – Die Nekropole des späten 8. bis frühen 6. Jahrhunderts. Kerameikos VI 2, Berlin.

Lentini, M. C. (1998) – “Nuovi rinvenimenti di ceramica euboica a Naxos di Sicilia”, in Bats, M. and d’Agostino, B., Euboica. L’Eubea e la presenza euboica in Calcidica e in Occidente, Napoli, 381-382.

Pfuhl, E. (1903) – “Der archaische Friedhof am Stadtberge von Thera”, Athenische Mitteilungen 28, 1-290.

Popham, R. H. and Sackett, L. H. (1979) – Lefkandi I: The Iron Age, Plates, London.

Poulsen, P. and Dugas, Ch. (1911) – “Vases archaïques de Délos”, Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 35, 350-422.

Rhomaios, K. A. (1929) – “H κάθαρσις της Δήλου και το εύρημα του Σταυροπούλλου”, Aρχαιολογικόν Δελτίον 12, 181-223.

Stavropoullos, D. (1898) – “Aνασκαϕαί εν Ρηνεία”, Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 100-105.

Tsuntas, Chr. (1886) – “Ανασκαϕαί τάϕων εν Ερετρία” Αρχαιολογική Εϕημερίς, 31-42.

Tsuntas, Chr. (1891) – “Ερέτρια”, Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 35-36.

Villard, F. (1993) – “La localisation des ateliers cycladiques de céramique géométrique et orientalisante”, in Dalongeville, R. and Rougemont, G., Recher ches dans les Cyclades. Coll. Maison de l’Orient méditerranéen 23, Lyon. 143-165.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

Fig. 20

____________

1 Hurst 1976.

2 Krause 1975.

3 Descœudres 1976.

4 A significant amount of 7th-century Eretrian pottery has come to light in Oropos, as reported by Xenia Charalambidou at the International Congress “Ancient Euboea in Antiquity”, held at Chalcis in October 2004. Bearing in mind the proximity of Oropos to Eretria and the very close ties that link the two sites to each other, one may hesitate to use the term “exports” for these vases.

5 Th.1.8; 3.104. For a brief account of the discovery and excavation of this deposit, see Stavropoullos 1898; for a first inventory of the finds, Rhomaios 1929.

6 I was given the opportunity to study and photograph both lots in 1971 and should like to express my gratitude for their generosity and assistance to Charalampros Sigalas, Photini Zapheiropoulou, and Pierre Amandry. My thanks to Nikolaus Kontoleon, though belated, are no less sincere.

7 See Kearsley 1989, 21-25.

8 Mid-8th cent.: kotyle Mykonos 893 (Descœudres 1976, 46 n. 173 pl. 1); 3rd quarter: high-rimmed skyphos Mykonos 1142 (Coldstream 1968, 191-192 pl. 41a; Descœudres 1976, 44 n. 135); Mykonos 907, of same type and fabric as Mykonos 1142 (Délos XV 82 Bb 53 pl. 40D); last quarter 8th cent.: skyphos Delos B 1944 (Descœudres 1976, 45 n. 158 pl. 4); kotyle Mykonos 902 (Descœudres 1976, 47 n. 190 Beil. 1 pl. 4); around 700 BC: mug Mykonos 904 (Descœudres 1976, 49 n. 222); skyphos Mykonos 774 (Descœudres 1976, 45 n. 163 pl. 4); aryballos Delos 7884 (Descœudres 1972).

9 Kourou 1998, 171 with refs.; see also Cook 19973, 340-341.

10 See Descœudres 1976, 16-17.

11 In Chalcis at the same time, the use of added white appears to be much less frequent, at least as far as one can tell from the available material: there is not a single example among the fragments published by Andreiomenou 1996.

12 Descœudres 1976, 39; Popham and Sackett 1979, pls. 52-57; Andreiomenou 1982, 173 nos. 97-98 pl. 26; p. 185 nos. 252-273 pls. 36-37; p. 185 n. 10 for further refs.

13 See Auberson and Schefold 1972, 97; Kahil 1981, 167; now also Erétrie. Guide 2004, 166. – My warm thanks to Jean-Robert Gisler for allowing me to study this material and to include here a number of pieces from this deposit, as well as for providing me with photographs.

14 Coldstream 1968, 179 pl. 38e.

15 See, e.g., Coldstream 1968, 50 pl. 9a.

16 Descœudres 1976, 42.

17 A few examples found in Sicilian Naxos, said to be of local manufacture, are very close in terms of both shape and decorative motifs to their Eretrian models: Lentini 1998, 381-382. This confirms the observation recently made by Kourou 1998, 168 that the pottery from Naxos in Sicily exhibits more than other Euboean colonies a distinctively Euboean appearance.

18 See Descœudres 1976, 37 with n. 45; Andreiomenou 1977, pl. 35.

19 Popham and Sacket 1979 pl. 38: 25; 60: 33.

20 Descœudres 1983, 36-38 no. 14 fig. 29.

21 Kearsley 1995, 10 no. 1 (but note that the fragments listed on p. 23 n. 36 as belonging to this group are in fact from a chalice-skyphos, not from a bowl-pyxis).

22 See, e.g., Andreiomenou 1981, 100-101 pl. 30.

23 Buschor 1929, 146 Beil. 52: 2.

24 For short preliminary reports on these first official excavations carried out in Eretria, see Tsuntas 1886; Tsuntas 1891; Kourouniotis 1897; Kourouniotis 1898; Kourouniotis 1900. For a first account of the grave-amphorae and other pottery found, Kourouniotis 1903.

25 Délos XVII, 21.

26 Brock 1949, 76-77.

27 See most recently Knauss 1997, 162-165.

28 Villard 1993, 148.

29 Délos XVII, 21.

30 Boardman 1952, 29.

31 Loc. cit.

32 Descœudres 1976, 40 pl. 6.

33 Ht. as pres. 4.5, l.(1) 25.6, l.(2) 8.2, l.(3) 4.5, diam mouth (reconstr.) 25 cm.

Clay well levigated, hard fired; very pale brown on the carefully polished surface (9YR 7 / 4), core slightly darker (7.5YR 6 / 5); occasional mica particles. Black paint micaceous, slightly brilliant, reddish-brown (2.5YR 4 / 5) where diluted. Added red (10R 4 / 4).

Main rim / shoulder fragment recomposed from 8 sherds; 12 non-joining fragments, 1 rim, 1 shoulder. Paint slightly worn in places.

Interior and handle painted. On the rim, frieze of small transversal bands, painted with a 7-headed brush, between red lines, applied directly on the clay ground. On the shoulder, A: animal frieze (part of a dog running to the right, filling ornaments); B: frieze of horizontal, voluted palmettes (leaves alternately black and red, the red applied directly on the clay ground).

34 Boardman 1957, 17 pl. 4.

35 For an early Archaic forerunner of the motif, see, e.g., Andreiomenou 1977, pl. 44.

36 Ht. 7.2, l. 8.5, diam mouth (reconstr.) 24 cm. Fabric as Delos 8997 (10).

Main fragment recomposed from 4 sherds, 4 smaller non-joining fragments not photographed.

Int. painted. On the lip, small transversal bands. Rim: frieze of hanging spirals between encircling bands, below a fillet in added red. On the upper part, dot frieze between bands, black and red. All added red applied directly on the carefully polished surface.

37 Kübler 1970, 368 n. 151 rightly notes the connection between Mykonos 662 and the Cynosarges workshop.

38 With the dinos fragment FK 368.1 was found a fragment of a Corinthian kotyle, FK 368.2, which must have looked not unlike the kotyle Oxford 121 that can be assigned a date around 630 / 10 BC (Transitional-Early Corinthian): CVA 2 IIIC pl. 1: 56 = Necrocorinthia no. 198 fig. 120A.

The same deposit in which the wall fragment FK 1377.1 was found produced also several Corinthian fragments. Despite their poor state of preservation there is no doubt that they stem from an olpe of Transitional style.

39 Dragendorff 1903, 210; Pfuhl 1903, 190-193.

40 Poulsen and Dugas 1911, 371-381.

41 See Knauss 1997, 4-5.

42 That these links continue throughout the 6th century is demonstrated by the important number of black-figure vases of Eretrian manufacture found on Delos and Rheneia, such as the amphora Mykonos 1028 (see Descreudres 1976, 38 n. 53).