The Singing Contest of Kithairon and Helikon

Korinna, fr. 654 PMG col. i and ii.1-11 : Content and Context1

This is an attempt to find a context for Korinna’s poem. For whom was it written? for what occasion? why did Korinna choose this subject? is there a time and place for the composition and performance of the poem which would have been more suitable than any other?

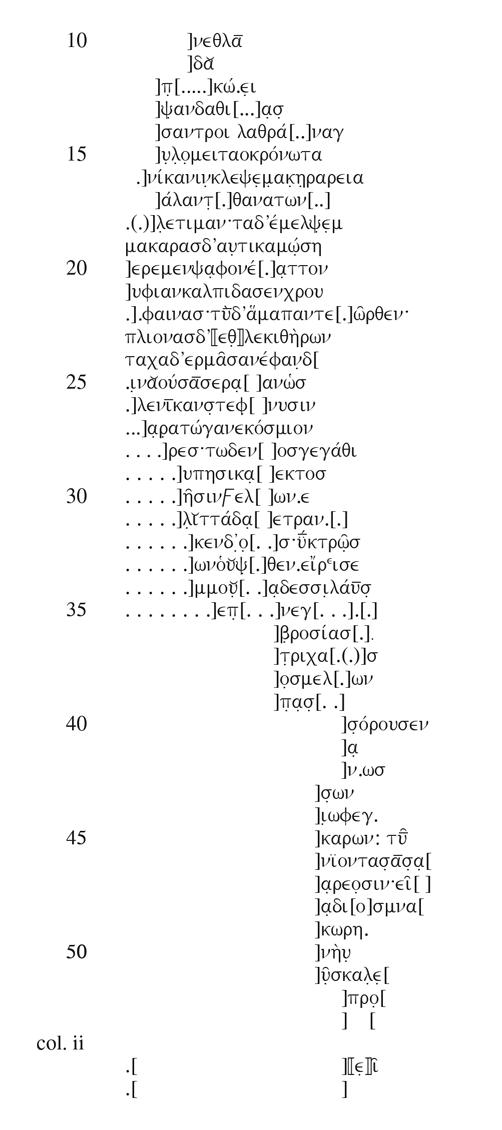

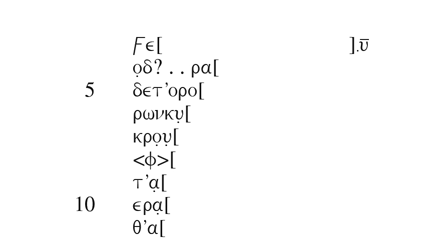

The Poem2

The text begins with the final 64 lines of a poem. Enough survives from lines 12-34 to give some idea of the content: it is about a singing contest between Kithairon and Helikon, with the gods as judges and the Muses presiding. Lines 12-18 contain the end of a song about the concealment of the infant Zeus from Kronos by the Kouretes and Rhea3. The gods vote, Kithairon wins and is overjoyed. Helikon takes the defeat badly and either kills himself or hurls rocks down from the mountain.

Most commentators have focussed on lines i.12-34, which are susceptible to more or less satisfactory restoration4. But the fragments which precede and follow these lines, and the marginal notes as well, offer important information.

i.1-11 (exempli gratia): “I (deserve) the crown (στέϕανον, ἔγωγε), because (ἐπιδὴ)… (when I was) at the very top (of the mountain) hunting (ἐπ’ ἄκρυ, marg.: θήραν… (I struck the) chords (of my lyre) (χορδὰς) (and sang of)… and sacred mountains (ἱ]αρῶν τ’ ὀρίων)… (and drew beasts and) birds (ϕοῦλον ὀρνί[θων) (by my singing)5… (and I sang of the birth) (γενέθλα) (of Zeus, how in) the snow (marg.: χιόνα), …

i.12-34: the Kouretes hid (the infant) in the hallowed cave of the goddess, concealed from devious Kronos, when blessed Rheia stole him away and gained great honour from the immortals”. This was his song, and straightway the Muses bade the blessed ones bear their voting pebbles in secret to the golden urns; they all rose in a group. Kithairon won the greater number, and straightway Hermes proclaimed with a shout that he had won the victory he longed for. The blessed ones adorned his head with wreaths, and his heart rejoiced. But Helikon, in the grip of dire wretchedness, (rushed to) a bare cliff, and piteously bewailing his lot he hurled (it or himself) down from on high in a shower of tens of thousands of rocks6. i.35-ii.11 (exempli gratia): … ambrosian (ἀμ]βροσίας)… hair (τρίχα)… limbs or songs (μελ[.]ων)… (possibly Kithairon) rushed (at him) (ἐ]σόρουσέν]… (or he joined Helikon in death, but at any rate they were both killed)… light? (ϕέγ[γ)… (something involving) the gods (μα]κάρων, and perhaps μακ]άρέσσιν)… the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (Δι[ὸ]ς Μναμοσούνας… κῶρη)… (the gods proclaimed that the mountains) were to be named after (them) (marg.: ἐπικληΘήσέσθαι), Helikon (Ғє[λικὼν)… (and) Kithairon (Κιθη]ρών), (where Zeus had been) concealed (]κρου[)…

On this reading what began as rivalry ends on a note of reconciliation.

Korinna’s Date

Scholarship is divided into two camps, one of which accepts the tradition of late antiquity which makes Korinna an older contemporary of Pindar, the other putting her into the Hellenistic period7. Partisans of the later date accept A. Kalkmann’s dismissal of the testimony of Tatian, Oratio ad Graecos 33, who refers to a statue of Korinna by Silanion (fl. 360-320)8. This was one of a group of statues in Rome of Greek poetesses by various sculptors, some of whom are not known from any other source.

The discovery in Rome of a statue base inscribed ΜΥΣΤΙΣ | AΡΙΣΤΟΔ̣ΟΤ̣[ου] has nullified Kalkmann’s argument, for among the statues in Tatian’s list is one of Mystis by Aristodotos9. If we accept Tatian’s account, as we must, then it follows that Korinna flourished before or during the lifetime of Silanion. This gives a terminus ante quem in the last quarter of the fourth century BC.

It does not, however, follow that Korinna was, as the tradition relates, contemporary with Pindar. Indeed, it is unlikely, for even in the poem under discussion here there are clues that she lived and wrote at the earliest during the third quarter of the fifth century. To be sure, there are echoes in the poem of Hesiod and Aischylos10, but two other passages seem to have later antecedents: ϕοῦλον ὀ̣ρ̣νί[θων] (i.6) is a direct quotation, both in words and context (that of hunting) from Sophokles, Antigone 342, which seems to have been performed for the first time at the end of the 440s11. And, as M. L. West has pointed out, the motif of Zeus being concealed by the Kouretes can be traced back only as far as a theogony attributed to “Epimenides” and dated ca. 430 BC12.

We now have a reasonable terminus post quem of the third quarter of the fifth century, and a terminus ante quem of the third or fourth quarter of the fourth. We can therefore look within that period for a possible occasion for the composition and performance of the poem, which might in turn help confirm the dating.

The Context of the Poem

It has been argued that the poem was written for the Plataians13. However, I think it is unlikely that the Plataians, who seized any and every opportunity to distance themselves from the rest of the Boiotians, would have commissioned a Boiotian poetess to write a poem for them in the Boiotian dialect14. Moreover, if I am right in my dating of Korinna, the Plataians would hardly have been in a position to do so. After the Theban attack on Plataia in 431, many of them fled to Athens. The rest surrendered to the Thebans in 427, and Plataia together with its satellite settlements was absorbed by Thebes15, remaining that way until, presumably, the King’s Peace of 386. Little more than a dozen years after that, in 373, the Thebans took Plataia and razed it again; it was not restored until after the battle of Chaironeia16. During this period the territory of Plataia was divided up among the Thebans17. Effectively, therefore, during the periods 427 to 386 and 373 to 338 the polis of Plataia did not exist and the territory of Plataia belonged to Thebes. It follows, on the one hand, that anything that happened at Plataia during these periods was done under Theban auspices, and on the other, that if Korinna wrote this poem as a commission for a public occasion, the commission was more likely to have come from the Thebans than from anyone else18.

The Thebans for their part had close connections with both Kithairon and the story of the birth of Zeus. It was on Kithairon that Amphion and Zethos were born. It was there that Oidipous was exposed, and it was on Kithairon that the women of Thebes traditionally celebrated their Dionysiac rituals. The Thebans regarded Kithairon as their own, and in their minds, Kithairon formed the southern edge of their χώρα.

As far as Zeus was concerned, Thebes was one of the places which claimed to be his birthplace19. In fact, Boiotian mythology is permeated by the tradition of the birth of a divine child. It goes back to the Bronze Age at least20, and is reflected not only in the stories of Ino-Leukothea and her child, but in the traditions of the birth of gods: Athena at Alalkomenai, Dionysos at Haliartos, Dionysos and Herakles at Thebes, Hermes at Tanagra, while the birth of Zeus was celebrated at Chaironeia and possibly Plataia in addition to Thebes.

There is a political dimension to these myths, since Zeus (Karaios or Akraios) was, with Athena, one of the two principal gods of the Boiotian ethnos. For the Thebans to claim that their polis was the birthplace of Zeus was, in the context of internal Boiotian politics, equivalent to claiming leadership of the country21. Zeus Karaios was originally a god of the Orchomenians and seems to have been co-opted by the Boiotoi in the second half of the sixth century BC. The Thebans completed their absorption of this Zeus into their own pantheon with the institution of the Basileia in his honour after the battle of Leuktra.

It would therefore have been appropriate for the Thebans to have commissioned a poem which celebrated both the birth of Zeus, the common god of the Boiotian ethnos, and Mount Kithairon.

There is another aspect of this poem. It not only glorifies Kithairon and Zeus, and thereby the Thebans, it also degrades Helikon and its gods, and through them the Thespians, whose mountain it was. If we search for a time when the Thebans might have wished to humiliate the Thespians, several come to mind, but only one can be connected with Helikon and its gods. In 479 the Thebans successfully urged the Persians to raze the city; in 423 they tore down the walls themselves, and in 414 they put down a democratic uprising. But in all these cases it was a matter of supporting or opposing whatever faction happened to be in the ascendant. It was different in the period 382-373, however, when the Thespians were actively allied with the Spartans, who had a harmost and garrison stationed there. It also seems likely that it was during this period of Spartan occupation and protection that the sanctuary of the Muses on Mount Helikon was formally instituted as an official cult of the polis22.

I suggest therefore that the most probable time for the performance of Korinna’s poem was after the suppression of Thespiai and Plataia, probably during the Theban hegemony. It may have been connected with the dedication at Plataia of the statues by Praxiteles of Hera Teleia and of Rhea and the stone23. Hera Teleia was the goddess of the Daidala, an ancient ritual celebrating national unity which goes back at least to the Bronze Age24, and it would have been most apt for the Thebans to have commissioned these statues at what was in fact a pan-Boiotian sanctuary (moreover one placed right under the eyes of the Athenians), and also to have commissioned a celebratory poem from the leading Boiotian poet of the day.

Several scholars have written disparagingly of Korinna’s poetry, her background and her intellectual powers. Admittedly in recent years there has been a reaction to this, particularly from those who write with a feminist agenda, but the point deserves to be made that on the evidence of this poem alone, Korinna was very well and widely read. The quotations of and allusions to earlier authors should be proof enough of this. If she chose to write in the Boiotian dialect (I do not say that the text as we have it necessarily reproduces the text she composed), she did so for a reason. And if she wrote, as I think she did, in the first half of the fourth century, which saw the highest point of Boiotian power and influence, her choice might have been made for nationalistic reasons. In the end, this did her reputation a disservice, for she has been branded provincial and parochial as a result.

*

The Text (fr. 654 PMG, incorporating West 1996):

]υστεϕανον

]γῶγ᾽ επὶδῆ

]επ᾽ άκρῡ

]χ̣ορδα̈́σ̣

5 ]α̣ρῶν τ᾽ ορειων

].ι̣ϕõυλο̣νο̣ρ̣νι

]

]

]. .

Notes:

i.13: δαθι: above δα, not an acute accent, but ζα; above ι, ε; 19: μω̣ση: above ω̣σ, ο̣υσ̣; 21-22: υ̣ above χρο̣υ;.].ϕαίνᾱσ ει above ί; 23: πλιον: ει above ι; εθλε: εῖ above εθ; 27:… ]α̣ρ̣ατώ or… ]δ̣ι̣ατώ; 30: final ε: ἑ, ɛ̌, or ἐ; 39: ]π̣α̣ο̣[or]π̣ι̣σ̣τ̣[.; 47: ο̣: ors σ̣; 51: ]υ̣σκαλ̣ε̣[: or δ̣ε̣; ii.4: ρα: or αρ/αιρ/αϕ In Margine:

at i.5: θηραν; 11: χ̣ι̣ο̣να or τ̣ι̣να; 21: ες; 37: εκ; 41: εις; 45: αερ̣[; 50: αποτου[

Bibliography

Bernard, P. (1985) -“Les rhytons de Nisa. I. Poétesses grecques”, Journal des Savants, 25-118.

Blanchegorge, E. (2003) – “Portrait de Corinne”, dans Jeammet, V., Tanagra. Mythe et archéologie, Paris, 189.

Burzacchini, G. (1990) – “Corinna e i Plateesi: In margine al certame di Elicone e Citerone”, Eikasmos 1, 31-35.

Burzacchini, G. (1991) – “Corinniana”, Eikasmos 2, 39-90.

Coarelli, F. (1969) – “La Mystis di Aristodotos”, Bollettino dei Musei comunali di Roma 16, 34-39.

Coarelli, F., (1971-1972) – “Il complesso pompeiano del Campo Marzio e la sua decorazione scultorea”, Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia di Archeologia 44, 99-122.

Ebert, J. (1978=1997) – “Zu Korinnas Gedicht vom Wettstreit zwischen Helikon und Kithairon”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 30, 5-12 = Agonismata. Kleine Schriften Stuttgart/Leipzig 1997, 53-62 (cited according to the latter).

Gentili, B./Lomiento, L. (2003) – “Corinna Le Asopidi (PMG Col. 3.12-51)”, dans Basson, A. F./Dominik, W. J., Literature, Art, History: Studies in Classical Antiquity and Tradition in Honour of W. J. Henderson, Frankfurt am Main, 211-223.

Gerber, D. E. (1970) – Euterpe, Amsterdam.

Gerber, D. E. (1994) – “Greek Lyric Poetry Since 1920. Part II. From Alcman To Fragmenta Adespota”, Lustrum 36, 7-188, esp. 152-162. 11. Corinna, Boeotica (157-159, nos. 1826-1836).

Hansen, M. H. (1996) – “An Inventory of Boiotian Poleis in the Archaic and Classical Periods”, dans Hansen, M. H., Intoduction to an Inventory of Poleis = Acts of the Copenhagen Polis Centre, vol. 3, Copenhagen, 73-116.

Kalkmann, A. (1887) – “Tatians Nachrichten über Kunstwerke”, Rheinisches Museum 42, 489-524.

Lewis, D. M. (1992) – dans CAH 5, Cambridge.

MacLachlan. B. C. (1997) – “Corinna”, dans Gerber, D. E., A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets, Leiden/New York/Köln, 213-220.

Page, D. L. (1953) – Corinna, London.

Prandi, L. (1988) – Platea: momenti e problemi della storia di una polis, Padua.

Rocchi, M. (1989) – “Kithairon et les fêtes des Daidala”, Dialogues d’Histoire Ancienne 15, 309-324.

Schachter, A. (1986) – Cults of Boiotia 2, London.

Schachter, A. (1994) – Cults of Boiotia 3, London.

Schachter, A. (2000) – “Greek Deities: Local and Panhellenic Identities”, dans Flensted-Jensen, P., Further studies in the ancient greek “polis”, Stuttgart, 9-17.

Segal, C. P. (1975) – “Pebbles in Golden Urns. The Date and Style of Corinna”, Eranos 73, 1-8.

Stewart, A. (1998) – “Nuggets: Mining the Texts Again”, American Journal of Archaeology 102, 271-282.

Stracca, B. M. Palumbo (1993) – “Corinna e il suo pubblico”, dans R. Pretagostini, Tradizione e innovazione nella cultura greca da Omero all’età ellenistica. Scritti in onore di Bruno Gentili 2, Rome, 403-412.

Teffeteller, A. (1995) – “Helikon’s Song. Korinna fr. 654 PMG ”, Eπετετηρίς της Eταιρείας Bοιωτικών Mελετών B’β’, Athens, 1073-1080.

Veneri, A. (1996) – “L’Elicona nella cultura tespiese intorno al III sec. a. C.: la stele di Euthy[kl]es», dans Hurst., A./Schachter, A., La Montagne des Muses, Genève, 73-86.

Vivante, P. (1979) – “Korinna’s Singing Mountains”, Teiresias Supplement 2, Montreal, 83-86.

Weiler, I. (1974) – Der Agon im Mythos: zur Einstellung der Griechen zum Wettkampf, Darmstadt.

West, M. L. (1990) – “Dating Corinna”, Classical Quarterly, 40, 553-557.

West, M.L. (1996) – “The Berlin Corinna”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 113, 22-23.

Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, U. von (1907) – dans Schubart, W./von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, U., Berliner Klassikertexte 5. Griechische Dichterfragmente 2. Lyrische und Dramatische Fragmente, Berlin.

____________

1 André Hurst and I are old friends, and I am grateful to the editors for inviting me to contribute to this volume in his honour.

2 The text printed at the end of this article takes into account the most recent revision of the Berlin papyrus by West 1996.

3 The first editor, Wilamowitz (1907, 47), attributed this song to Kithairon, but without giving reasons. They are cogently set out by Teffeteller 1995, 1074.

4 In chronological order: Wilamowitz 1907, 26-29; Page 1953, 19-22; Gerber 1970, 391 and 395-397; Weiler 1974, 80-89 and 98-99; Segal 1975; Vivante 1979; Ebert 1978=1997; Rocchi 1989, 309-313; Burzacchini 1990 and 1991, 64-80; Teffeteller 1995; Veneri 1996, 74-77; MacLachlan 1997, 218-219.

For Vivante, the protagonists are the mountains themselves, but most others take them to be mortals after whom the mountains were named. The most detailed study to date is Burzacchini 1991, 64-80.

5 The image here is perhaps of Orpheus: cf. Simon. fr. 567 PMG.

6 This is a remarkably accurate description of the slopes of Mount Helikon, which are covered with scree (“a mass of detritus, forming a precipitous, stony slope upon a mountain side”: Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, sv.).

For most scholars Helikon wrenches a rock from the mountains, hurls it down, and it shatters into tens of thousands of fragments. Ebert, 1978 = 1997, however, has Helikon hurl himself down in a shower of stones.

7 See most recently Gentili/Lomiento 2003, 221-223, with references, to which add: Bernard 1985, 97-115; West 1990; Gerber 1994, 152-155; West 1996; Stewart 1998, 278-281.

8 Kalkmann 1887, cited with approval by Page (1953, 73 note 6) and West 1990, 557.

9 IGUR 212. The significance of this inscription was noticed by Coarelli 1971-1972, cf. Coarelli 1969. Coarelli’s work is cited by Bernard (1985, 70-74), who suggests that the statues which Tatian saw in Rome came originally from an exedra in Boiotia, possibly at Helikon. Coarelli’s and Bernard’s articles are cited by Stracca 1993, 411412. The first English-speaking scholar to take note of it was Gerber 1994, 159; the first to take it seriously was Stewart (1998, 278-281), who also cites a marble statuette of Roman date in the Musée Vivenel, Compiègne (his figure 4) inscribed Κόριννα on the base, regarding it (as others had done before him) as a copy of the original by Silanion (“persuasively late fourth century in dress and coiffure”). See Blanchegorge 2003 for a description, illustration, and bibliography of the statuette. The name of Mystis (Μυστίδος), which appears in all three manuscripts of Tatian, was emended by H. Brunn to Νοσσίδος. This reading is printed by all subsequent editors. It is to be rejected.

10 For example, i.12-15, with which compare Hes.Th.482-483; and with i.31, λιττάδα [π]έτραν compare A.Supp.792-797, and closer in time, E.HF1148.

11 S.Ant.342-347. In the margin of the papyrus, to the right of i.5, is the word θηραν.

12 1990, 555. On the same page, West cites δάθιο[ (i. 13, qualifying [βρέϕο]ς) as an example of a usage which is Hellenistic at the earliest. On revising the papyrus, however, he observed that what had appeared as an acute accent over the a was in fact no such thing, and was to be discarded as evidence for the late date: West 1996, 22.

13 Burzacchini 1990.

14 In fact, Herakleides Kretikos called both the Plataians (1.11) and Oropians (1.7) Ἀθηναῖοί Bοιωτοί, “Athenian Boiotians”.

On the vicissitudes of Plataia’s political allegiance during the fifth and fourth centuries, see Hansen 1996, 100-101.

15 431: Lewis 1992, 393-394. 427: Lewis 1992, 406-407. Absorption by Thebes: Hell. Oxy. 385-390 Chambers.

16 Prandi 1988, 121-132. The exact date of the restoration is uncertain.

17 Isoc. Plataiikos (14) 7.

18 It is possible, of course, that the poem was written for performance during the brief interval between 386 and 373 when Plataia was independent. However, the instability of the region and the uncertain allegiance of the Plataians at the time make it unlikely that they could – let alone would – have commissioned this or any other poem, especially one composed in the Boiotian dialect.

19 There was a place at Thebes called Διὸς γοναί: Aristodem. of Thebes, FGrH 383F7 (Schol. AB, Il. 13.1).

20 See, for example, Schachter 1994, 17.

21 See Schachter 1994, 145-146.

22 Schachter 1986, 156-157.

23 Paus.9.2.7.

24 When it was called the Teleia (in a Theban Linear B tablet): Schachter 2000, 12, 13-14.