How to sell a Carolingian illuminated manuscript in the nineteenth century ?

The Basle book-dealer J. H. von Speyr-Passavant and the « Moutier-Grandval Bible »

The research for this article has been undertaken as part of the CULTIVATE MSS project, which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 817988).

In early 1829, several French newspapers announced that Mr. Speyr-Passavant, citizen of Basle, had arrived in Paris with the greatest palaeographical treasure ever produced: the Bible that Alcuin of York wrote and presented to Charlemagne for his coronation. Distinguished librarians, bibliographers, and historians, members of the royal family, political and religious authorities had expressed their admiration on viewing the manuscript and wished that it remained in France. The press also reported that the item was the most complete, exquisite, and authentic book of Charlemagne’s reign. Evidence for this was provided by the presence of Alcuin’s poem celebrating his revision of the biblical text, Tironian notes, symbols of French royalty, and a full-page miniature representing Charlemagne receiving the Bible. It is reasonable to assume that Speyr-Passavant himself drafted these articles to persuade the French government to acquire his manuscript. But, despite this sensational announcement, he failed to find a purchaser in Paris, – he eventually sold it to the British Museum in 1836.

This manuscript, known as the « Moutier-Grandval Bible », named after the Benedictine Abbey, now in the canton of Berne which once owned it, is one of the three surviving monumental illustrated Bibles produced at Tours in the first half of the ninth century, – it is today Add. MS 10546 in the British Library. As such, it has been the object of numerous studies, focusing on its date of production, contents, scripts, decoration, and provenance history1. The aim of the present contribution is to explore in greater detail Speyr-Passavant’s methods of selling this outstanding book across Europe. As he established the Bible’s date of production partly through the analysis of its initials and miniatures, this case study examines how a manuscript’s decoration could be exploited by a book-dealer to determine its financial value.

Numerous sources are available to conduct this investigation. It includes eleven letters, now in the Staatsarchiv of the canton of Basle-Stadt, that Speyr-Passavant wrote from 1822 to 1824 to his cousin Jakob Burckhardt, a historian and Protestant minister at Basle2. In addition, the Album, a large notebook in the British Library, contains Speyr-Passavant’s research notes and correspondence, as well as newspaper articles on the Bible3. In October 1829, he used part of this material to compile the essay Description de la Bible écrite par Alchuin, providing valuable insights into his approaches of studying and marketing the book4. To these can be added a file of copies of letters and notes that Speyr-Passavant produced between 1830 and 1836, now in the Basle Universitätsbibliothek5. Together with information from the Bible, the analysis of this rich material makes it possible to follow Speyr-Passavant’s remarkable and lengthy endeavours to sell his manuscript and how he exploited its decoration to do so.

Before exploring this story, it is worth briefly introducing the dealer, the manuscript, and its decoration. The fate of the Bible is intimately linked to that of Johann Heinrich von Speyr-Passavant (1782-1852), who citizens of Basle nicknamed « Bibel-Spyr ». Having been trained as a merchant in Basle and London, Speyr-Passavant took over in 1816 his father’s shop Zum Halben Mond, located in the centre of the city of Basle, and ran, at least since 1826, a second store Zum Grünen Helm, where he also later exhibited his art collection. Besides his dealing activities, Speyr-Passavant was a keen art- and book-collector and gathered about 30,000 books, medieval altarpieces, including some deriving from the church at Baden in the canton of Aargau, from the Franciscan monastery at Lucerne, and other paintings attributed to Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein, Jan Van Eyck, and Michael Wolgemut, along with stained glass, tapestries, and reliquaries6.

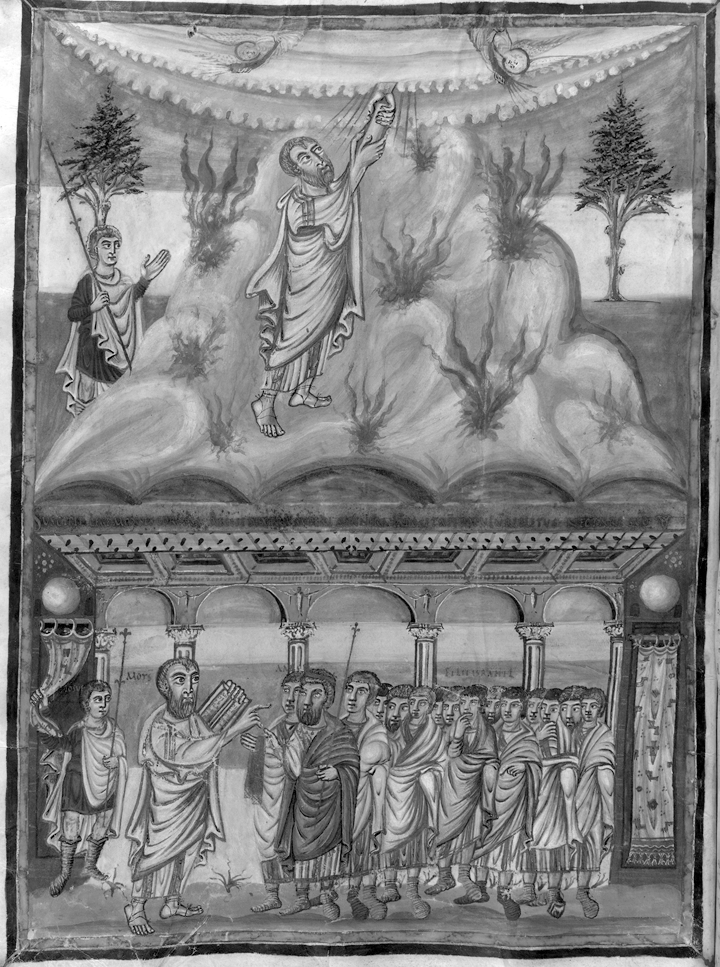

As for the manuscript, it was produced in the scriptorium of the Benedictine Abbey of St Martin at Tours, probably in the 830s-840s7. Measuring 510 × 375 mm and made of 449 parchment folios, it contains the entire text of Alcuin’s revised version of the Bible. One of its distinctive features is its rich decoration, making it a magnificent specimen of Carolingian art. In addition to large decorated and historiated initials at the beginning of every section of the text, the manuscript also contains four canon tables to the Gospels and two tables to the Pauline epistles set in architectural and ornamental composition8. What contributes even more to its singularity are the four full-page miniatures and the ornamented incipit page introducing Jerome’s letter to Paulinus with the title written in gold on purple straps9. Painted before the book of Genesis, the first miniature shows the account of the Creation and the Fall of Adam and Eve. The second, at the beginning of Exodus, contains two scenes: one represents Moses, with Joshua, receiving the Tablets of the Law; the other illustrates Moses giving the Tablets to the Israelites guided by Aaron. In the third miniature, preceding the Gospel of Matthew, Christ in Majesty holds a book and is surrounded by the symbols of the Evangelists and the four main prophets. The last image, located after the Apocalypse of John, is made of two registers. In the upper part, the Lamb and the Lion of Judah open the book of Revelation, while the symbols of the four evangelists are painted in each corner. In the lower part, an old man holds a cloth over his head and is surrounded by the symbols of the evangelists, who deliver him the message of the Gospels10.

As other Carolingian Bibles written at Tours, the manuscript was produced as a gift; it is, however, hard to identify its first owner. Although it is possible that the monks of Moutier-Grandval directly obtained it or that a member of the family of the Duchy of Upper Alsace received it and later offered it to the Abbey, one of its properties founded around 640, no material evidence in the book confirms this early provenance11. The presence of the Bible in the community of Moutier-Grandval, turned into a collegiate church in the early twelfth century, is definitely attested in the early seventeenth century by a list of canons written at the end of the volume and dated between 1595 and 1606, according to the names recorded12. At the Reformation, the Moutier-Grandval collegiate church was destroyed and the community fled in 1534 to Delémont, a nearby city located in the Prince-Bishopric of Basle, bringing their possessions, including their Bible. The canons remained there until 1792, when the French army invaded the city, during the War of the First Coalition; they moved back to Moutier in 1793, before settling definitively in Solothurn in 179713. Although they arranged the transfer of most of their belongings to their new residence, the Bible remained at Delémont hidden in the house of Claude-Joseph Verdat, a civil servant, who had helped them leave the city.

The Bible’s subsequent history is difficult to reconstruct precisely and local scholars have somewhat embellished it. Some mentioned that Verdat’s daughters found the book in the attic of their father’s home and sold it to Joseph-Alexis Bennot, former mayor of Delémont, in 182214. Recent research has, however, revealed that the sale to Bennot occurred between 1812, when Verdat died, and 1818, when his last daughter left the family’s house15. The exact sale price remains unknown and historians have suggested the sum of 3 French francs 75 centimes (25 Swiss batz) or of 3 French francs 60 centimes (24 Swiss batz), both options being ridiculously low.

Although the circumstances in which Bennot purchased the Bible remain unclear, archival evidence indicates that he approached various potential buyers, including Daniel Huber, director of the Basle Öffentliche Bibliothek der Universität. Their contacts are known from a letter written on 15 July 1836 by the historian Jacob Burckhardt, the son of Speyr-Passavant’s correspondent, to Heinrich Schreiber, Professor of Theology at the University of Freiburg im Breisgau. In this, Burckhardt complained that Huber had declined Bennot’s offer of 10 louis d’or for the manuscript, without giving the date of this unsuccessful attempt16.

Despite this refusal, Bennot continued to look for purchasers and, for this purpose, compiled a brief description of the Bible, – this reveals that he utilized the manuscript’s decoration to attract clients17. In addition to information about its contents, material, size, text layout, and binding, Bennot stressed that the volume contained « beaucoup de peintures qui attestent son antiquité de dix siècles et plus ». It is difficult to know how and when Bennot circulated this description, but in anticipation of the sale he forwarded it to Speyr-Passavant. Along with this document, Speyr-Passavant’s correspondence with Burckhardt provides further insights into how the transaction took place. On 17 March 1822, Speyr-Passavant enthusiastically recounted his cousin that he examined a very old Bible written on parchment and illuminated with « merkwürdige Mahlereyen ». Having immediately noticed the rarity of the manuscript, he bought it on 19 March 1822, as shows a copy of the sale agreement in the Album18. In this, Speyr-Passavant deliberately omitted the sum he paid, but subsequent historians reported prices in various currencies, varying from 288 Swiss francs, 24 louis d’or (480 Swiss francs) and 25 louis d’or.

After the sale, Speyr-Passavant quickly started studying the Bible, but, as he somewhat struggled to read some parts of the text, solicited Burckhardt’s help to transcribe and translate into German Alcuin’s poem and epigrams19. Having coped with this initial challenge, he then explored the book’s early history and that of the abbey of Moutier-Grandval; his readings included, in particular, Christian Wurstisen’s Bassler Chronick and an unidentified chronicle entitled Histoire manuscrite en latin des actes memorables du ci devant chapitre de Motier Grandval20.

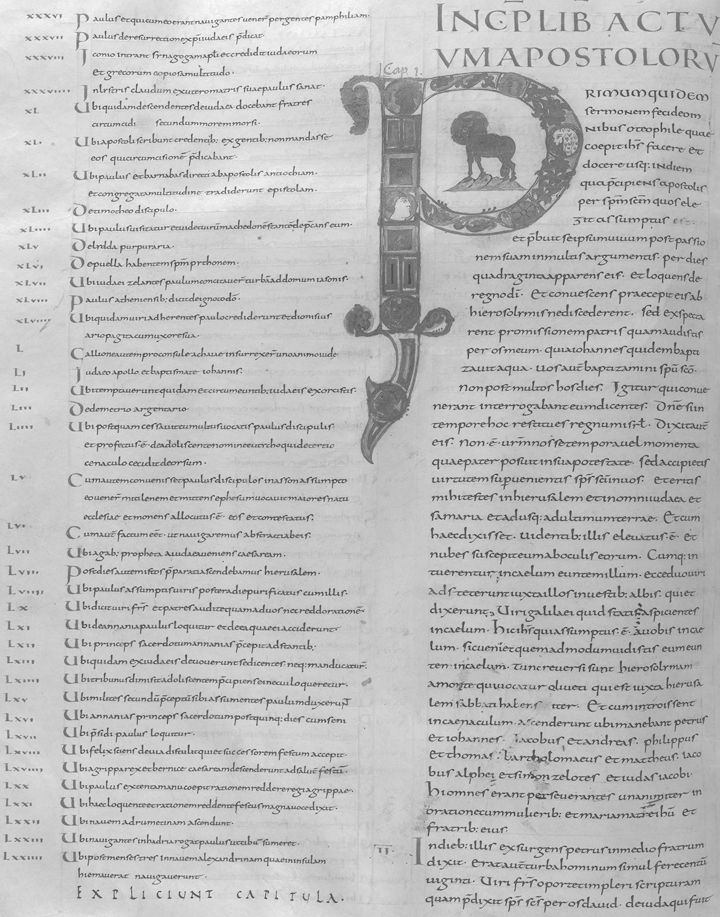

In early September 1822, Speyr-Passavant informed Burckhardt that his research led him to the conclusion that Charlemagne presumably ordered the monks of the Benedictine Abbey of Prüm, closely linked to Carolingian rulers and today in the diocese of Trier, to produce this manuscript21. According to him, when this monastery was suppressed in 1576, the Bible was then sent to the Abbey of Moutier-Grandval, as revealed by the inscription listing the canons written around 1600. As well as collecting evidence from scholarly accounts, Speyr-Passavant also claimed that the decoration clearly demonstrated that the book was produced at Prüm. He explained to Burckhardt that the historiated initial « P », painted at the beginning of Acts of the Apostles, represented the Abbey of Prüm, since it contained its coat of arms, that is a lamb with a halo standing on a hill [ill. 1]22. He added that « Primum », the word introduced by this initial, also stands for the Abbey, whose original name « Primum » had evolved into « Prim » and « Prum ».

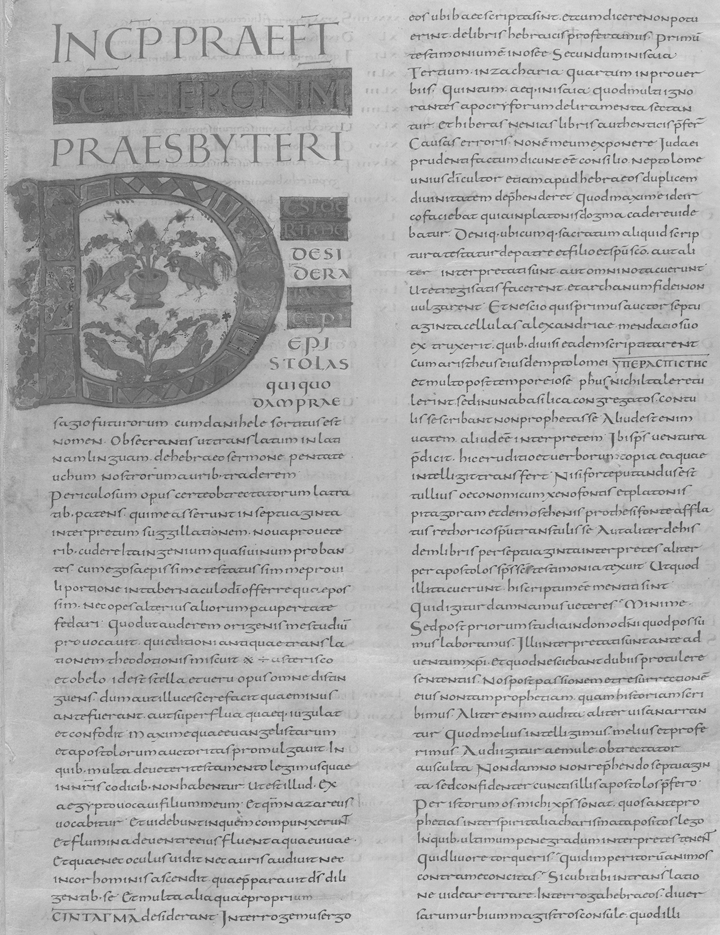

Subsequent letters show that Speyr-Passavant continued to refer to the decoration to support his hypothesis, associating the Bible with Charlemagne. In an undated report sent to Burckhardt, he analysed the initial « D » at the beginning of the word « Desiderii », introducing Jerome’s preface to Genesis [ill. 2]23. This time, he focused on the two cocks in it, explaining that they symbolized the kings who ruled over Gaul and could either be Charlemagne and his father Pepin the Short or Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious – his interpretation came from the fact that the Latin word « gallus » could mean « cock » and « Gaul ». In addition, Speyr-Passavant reported that the word « Desiderii » referred to the Lombard king Desiderius, Charlemagne’s father-in-law, therefore providing clear evidence of the Bible’s first owner.

Ill. 1. London, BL, Add. MS 10546, f. 390v.

Ill. 2. London, BL, Add. MS 10546, f. 6r.

The architectural composition of the tables to the Gospels and the Epistles also played an important role in Speyr-Passavant’s investigation. While re-working on the Bible’s early provenance history, he gave an alternative account to its arrival in the diocese of Basle. In a later letter to Burckhardt, he suggested that the manuscript presumably belonged to the Basle Minster from the reign of Charlemagne onwards or that of his grandson Charles the Bald, who, as he claimed, were both its benefactors24. To confirm his idea, he said that « Gaul »-style arches painted in the book must have been similar to those in the first cathedral, destroyed in 917 but of which traces were still visible in the new building, especially in the window above the main entrance. Since his correspondence with Burckhardt is incomplete, it is hard to know precisely what aspect of the book he explored next and when he eventually determined that Alcuin wrote it at Tours for Charlemagne, who mentioned it in his will and bequeathed it to his heirs, until his grandson Lothair I gave it to the Abbey of Prüm, where he died in 855.

Better known are, however, Speyr-Passavant’s endeavours to preserve the manuscript as he later described them in his essay Description de la Bible écrite par Alchuin25. In this, he related how he succeeded in saving it from destruction and in restoring its original royal ownership, in spite of its « état pitoyable de détérioration ». He explained that he covered the late medieval binding, whose boards were wormed, in black velvet and cleaned the parchment leaves by leaving the book in a heating stove for a year. He also put the Bible in a metal box lined with crimson velvet embroidered with gold fleurs-de-lys, a silver cross, and the Crown of France. As Speyr-Passavant observed, the manuscript’s new appearance then illustrated the royal status of its first owner, Charlemagne.

Once he completed the restoration, it seems that Speyr-Passavant travelled to Germany to make the Bible known to the public26. Among those who consulted the manuscript was Johann Leonhard Hug, Professor of Old and New Testament at the University of Freiburg im Breisgau. After their meeting, Speyr-Passavant sent him his conclusions about the Bible’s date of production27. Although it is difficult to know whether they corresponded afterwards, Hug kept on studying the item and included a short chapter on it in the third edition of his work Einleitung in die Schriften des Neuen Testaments, published in 182628. There, he noted that one of the most distinctive variants of Alcuin’s revised version of the Bible, an extract from the First Epistle to John, was missing in Speyr-Passavant’s manuscript, thus casting doubt on its genuineness. Hug also recounted that he would explore in more detail the book’s palaeographical peculiarities in a subsequent contribution.

Following this publication, Speyr-Passavant resumed collecting material supporting his statements on the manuscript’s date of production. To confirm his theory, he carried out a great deal of research not only on the volume, its text and decoration, but also on Alcuin and his work for Charlemagne at Tours, as well as on the Abbey of Moutier-Grandval. Furthermore, he studied the contents and the production of two other Carolingian Bibles: that of Vivien, also known as Première Bible de Charles le Chauve, written around 845, and in the Bibliothèque royale in Paris, and that of the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome, produced in the 870s29. The Album contains his numerous research notes and extracts he copied from accounts on theological history and palaeography, including Caesar Baronius’s Annales ecclesiastici, Jean Mabillon’s De re diplomatica, and Johann Jakob Wettstein’s Prolegomena ad Novi Testamenti30.

Besides gathering information from academic literature, Speyr-Passavant invited experts in book history and theology together with religious and political authorities to examine the book and collected their signatures and their thoughts on the Bible. Among the visitors he received in his shop at Basle was Gustav Hänel, Professor of Roman Law at the University of Leipzig, who had been travelling across Europe since 1821 to consult manuscripts31. In autumn 1828, Speyr-Passavant took his book on a tour to Switzerland and met some of the country’s most renowned personalities. In Geneva and Lausanne, where he stayed in late October 1828, he showed the volume to Jacob-Élisée Cellérier, Professor of Hebrew at Geneva, Jean-Jacques-Caton Chenevière, Professor of Dogmatic theology and Rector of the Academy of Geneva, Louis Gilliéron, Professor of Physics and librarian of the Academy of Lausanne, and André Gindroz, Professor of Philosophy at Lausanne. On 2 November 1828, he arrived in the Jesuit College in Fribourg and presented the Bible to Mgr Pierre Tobie Yenni, Bishop of the diocese of Lausanne, Johann Baptist Drach, Provincial of the Swiss Province of the Jesuits, and further representatives of Fribourg religious houses, including Charles-Aloyse Fontaine, Canon of St Nicolas and book-collector, Johannes Janssen, Rector of the Jesuit College, and Louis Guillet, Warden of the Franciscan monastery. Then, he headed for Berne and put the manuscript on display in the Stadtbibliothek, where Marie Joseph d’Horrer, chargé d’affaires de France en Suisse, Samuel Studer, first dean of the Berne Church, and Franz Sigmund Wagner, Berne’s book-censor and member of the Bibliothekskommission, consulted it. After a visit in Thun, where he showed the Bible to Niklaus Friedrich von Mülinen, former President of the Helvetian Confederation, an historian and book-collector, Speyr-Passavant stayed in the city of Langenthal, where members of the nearby Cistercian monastery of St Urban, including Abbot Friedrich Pfluger and librarian Urban Winistoerfer, came to see it. On 11 November 1828, in Solothurn, he met Josef Hermenegild Arregger von Wildensteg, genealogist and avoyer of the canton, Canon Konrad Josef Glutz von Blotzheim, and Peter Ignaz Scherer, city librarian32. These personalities’ comments suggest that Speyr-Passavant travelled through Switzerland to gather opinions supporting the authenticity of the Bible. Whereas some only wrote down their names, the contents of others’ observations demonstrate that he made it sure that visitors reported that they were examining an important book. Many recounted their enthusiasm in viewing an extremely rare manuscript and some of them, such as Drach and Yenni, unquestionably associated it with Charlemagne and Alcuin.

Once he returned to Basle, on 14 November 1828, Speyr-Passavant collected the comments of three scholars, whom he knew well: his cousin Burckhardt, Daniel Huber, director of the Öffentliche Bibliothek der Universität, and Hieronymus Falkeisen, head of the Basle Reformed Church33. In their statements, they all deplored the fact that he decided to leave the city, because local authorities and institutions were unwilling to buy his precious Bible, – these consist of the first clear evidence indicating that Speyr-Passavant’s objective was to sell the manuscript.

Speyr-Passavant therefore looked for a buyer elsewhere and decided to travel to Paris. There is a variety of reasons for his choice of destination. First, as the city had been the European centre of the antiquarian book-trade in the late eighteenth century and still attracted many book-collectors, Speyr-Passavant hoped to find clients easily there. Furthermore, he considered the Bibliothèque royale the Bible’s rightful home, since it owned the libraries of other French monarchs. It is worth mentioning that France’s delegate in Switzerland, Horrer encouraged him to travel to Paris to offer the manuscript to the King; later Speyr-Passavant also received support from Maximilien Gérard de Rayneval, French ambassador in Switzerland34. Moreover, Paris was the ideal place to study the Bible further, by consulting additional Carolingian manuscripts and scholarly documentation. For this purpose, librarian Daniel Huber wrote, on 25 November 1828, a reference letter, asking his Parisian colleagues to assist Speyr-Passavant in his investigation35. In addition to these, Hug published in late November 1828 his second article on the Bible, in which he demonstrated that this book could not have been produced for Charlemagne, but more likely for his grandson Charles the Bald, who reigned between 845 and 87536. This result also certainly encouraged Speyr-Passavant to conduct more research on his manuscript.

On his arrival in Paris, in early December 1828, Speyr-Passavant lost no time in showing his Bible to scholars, who again signed his Album. These include librarians working at the Bibliothèque royale, such as Jacques-Joseph Champollion-Figeac, keeper of manuscripts and Professor of palaeography at the École des Chartes, Théophile Marion Dumersan, keeper of médailles et antiques, Benjamin Guérard, specialist of Carolingian books, and Joseph van Praet, keeper of printed books, and their colleagues Joseph Flocon, director of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, and Charles Nodier, librarian at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal. These were joined by the dealers Jean-Jacques Debure and his brother Marie-Jacques, Ambroise Firmin-Didot, and Antoine-Augustin Renouard, as well as by the book-collectors Hippolyte de Châteaugiron, Agricol-Joseph Fortia d’Urban, and Scipion Du Roure, all members of the Société des bibliophiles françois. Along with researchers, Speyr-Passavant met religious officials, including Paul-Henri Marron, president of the Consistoire de l’église réformée of Paris and Mgr Hyacinthe-Louis de Quélen, Archbishop of Paris37. Like during his journey in Switzerland, Speyr-Passavant took great care in securing enthusiastic comments, as most visitors confirmed that the Bible dated from the time of Charlemagne.

On 24 December 1828, King Charles X granted Speyr-Passavant an audience at the Palais des Tuileries so that he could view the Bible. For this occasion, Speyr-Passavant prepared a long report, in which he explained that the manuscript was produced for a French monarch38. Here again, he used the decoration to support his theory, mentioning that various symbols in the initials, the cocks in the initial « D », fleurs-de-lys visible in miniatures, and the style of architecture in canon tables proved Charlemagne’s ownership.Confident that further specialists would confirm his investigation, he asked the King to appoint experts to examine his manuscript, so that he could present it to him. His demonstration and request, however, did not convince Charles X, who declined formally to acquire the Bible in late January 182939.

Despite this negative outcome, numerous letters indicate that Speyr-Passavant spent a lot of time trying to sell the Bible to the French government. On 3 February 1829, Joseph-Balthazard Siméon, Director des Belles Lettres, Sciences et Beaux-Arts, advised him to discuss this with the Bibliothèque royale’s administrateurs. He therefore wrote to the library’s Président Bon-Joseph Dacier, who inquired about the price of the book. In his replies collected in the Album, Speyr-Passavant carefully crossed out the sum that he envisaged, but annotations, likely added later by Sir Frederic Madden, librarian at the British Museum, reveal that the first offer amounted to 60,000 French francs. Since Dacier considered this too expensive, Speyr-Passavant revised his proposal, proposing a sale for 48,000 and finally 42,000 French francs. Although he lowered his price, Dacier could not buy the Bible due to lack of funding40. In addition to French officials, Speyr-Passavant offered his book to representatives of other countries during his stay at Paris; letters in the Album demonstrate that he was in touch with Sir Charles Stuart, Baron Stuart de Rothesay, British ambassador to France, and Pietro Antonio Garibaldi on behalf of Luigi Lambruschini, Apostolic nuncio in Paris; neither of them agreed to acquire the manuscript41.

As well as looking for purchasers, Speyr-Passavant continued to show his manuscript to Parisian scholars. According to several newspaper articles issued from 19 January to 14 February 1829 in Le Constitutionnel, Le Courrier, Gazette de France, Journal des débats politiques et litéraires, Journal des dames et des modes, Messager des chambres, Le Moniteur universel, La Quotidienne, L’Universel, members of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres invited him to one of their meetings. He also put the Bible on display in the library of the Chambre des députés42.

Although Speyr-Passavant attracted a great deal of attention, some started to question the authenticity of his volume, among them was the eminent bibliographer and Inspecteur de l’Académie royale at Dijon, Gabriel Peignot. Reacting to articles published in a local newspaper in February 1829 and reporting Speyr-Passavant’s sensational findings, Peignot, who had not examined the manuscript, explained that the Bible was certainly not the only notable Carolingian book in France, – the Bibliothèque royale indeed owned Charlemagne’s book of Hours, the Godescalc Gospels43. Moreover, he mentioned that Alcuin could not have possibly produced such an enormous book for Charlemagne’s coronation, because he was too old and involved in other projects at that time44. Having learned about this publication, Speyr-Passavant wrote to Peignot in late May 1829, praying him to re-consider his claims in light of additional information that he collected during his research in Paris and that he forwarded him. Since he had not seen it, Peignot agreed to study in more detail the Bible and promised to compile soon a new account containing a revised description of it45.

But new suspicions about the manuscript’s date of production continued to appear in the scholarly literature. In early September 1829, a review of Catalogi librorum manuscriptorum, Gustave Hänel’s work recording the books consulted on his visit to European libraries, was issued in L’Universel and La Quotidienne. It stated that, according to Hänel, palaeographical evidence suggested that the Bible dated to the tenth century46. Although he saw the manuscript at Basle and listed Speyr-Passavant’s medieval books among other Swiss collections, Hänel included the entry for the Bible in the part dedicated to Parisian libraries47. The long record he produced of the item contained its description as issued in Le Constitutionel on 5 February 1829, account of Hug’s analysis, suggesting a later date of production, and a report by the English book-collector Sir Thomas Phillipps, who believed too that it was written in the tenth century.

In response to these accusations, Speyr-Passavant wrote a first article in Gazette des cultes on 11 September 1829 and a second more substantial account in La Quotidienne on 16 September 1829, explaining why he disagreed with Hänel48. Furthermore, he decided to make his complete investigation known to a wider readership through his essay Description de la Bible écrite par Alchuin, which he published in October 1829. After a dedication to Peignot, who by then supported his conclusion, Speyr-Passavant recounted the history of the Bible from its production by Alcuin, presentation to Charlemagne, entry in the monastery of Prüm, transfer to that of Moutier-Grandval, and to its sale by Bennot in 1822. After detailing how he restored the manuscript, emphasizing that it recovered its original royal status, Speyr-Passavant offered an account of its contents and scripts.

These were followed by a part entitled « Description du contenu », which included a long analysis of the full-page miniatures. This section clearly indicates again that Speyr-Passavant deliberately used the decoration for marketing purposes by establishing links between biblical accounts and Carolingian figures. Although he identified evidence for Alcuin or Charlemagne in the four paintings, his interpretation of the second miniature illustrates particularly well his objective [ill. 3]. He explained that the scene in the upper part of this image showed Alcuin with Louis the Pious, painted as Moses and Joshua, receiving the Tablets of the Law from God. Then he claimed that the lower part represented Alcuin offering the book to Charlemagne. In addition, Speyr-Passavant reported that the sceptres held by the characters portraying Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, their red clothes, as well as the fleur-de-lys painted in and around the image, were evident elements of the French royalty. Besides the miniatures, Speyr-Passavant observed that, according to scholars, the architecture of the canon tables was unique. As this could not be found in other Carolingian Bibles in Rome and Paris, it unquestionably confirmed the genuineness of his book. Afterwards, Speyr-Passavant turned to the Vallicelliana Bible to demonstrate that it was not the book produced by Alcuin, as Étienne Baluze and Baronius had suggested49. His analysis of this manuscript’s decoration played a key role in proving that his book was Charlemagne’s Bible. In particular, he noted that the Vallicelliana Bible contained no evidence of the royal ownership, whereas the miniatures of his volume illustrated Alcuin’s gratitude to Charlemagne, since they represented him and his son.

Ill. 3. London, BL, Add. MS 10546, f. 25v.

The subsequent parts of the essay dealt with proving the manuscript’s early date of production in reply to Hug’s and Hänel’s allegations. For this purpose, Speyr-Passavant presented their analyses and then reproduced newspapers articles supporting his theory. These were followed by Peignot’s letters initially challenging the Bible’s authenticity and Speyr-Passavant’s answers to these. The next section headed « Opinions des journaux » contained press articles on the manuscript published in France from January 1829 onwards. Afterwards, to confirm his findings, Speyr-Passavant inserted a section entitled « Certificats des savans de la capitale », containing thirty-eight statements, which validated the Bible’s early date of production. In addition to the comments by experts who had viewed the book soon after his arrival in Paris, Speyr-Passavant included those of individuals, whom he met later, such as the bibliographer Jacques-Charles Brunet, abbé Henri Grégoire, the historian and politician François Guizot, Matthew Luscombe, Anglican bishop in Paris, and Louis-Aimé Martin, curator at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. One should emphasize that, while the first declarations mainly reported the visitors’ satisfaction in consulting the Bible, the great majority of subsequent opinions, presumably influenced by Speyr-Passavant, stated that the manuscript should remain in a French library50. Concluding his work, Speyr-Passavant summed up his claims, called for further research on the Bible, and urged the French government to acquire it:

« Fassent Leurs Excellences les ministres de Sa Majesté Charles X, que la France n’ait pas la douleur de voir échapper à ses vœux un trésor d’un si grand prix pour elle !

Puissent les lettres, puisse la France surtout, être assez heureuse pour compter bientôt au nombre de ses richesses scientifiques un monument dont la possession semble devoir être de préférence son partage ! »51

Promoting his observations on the Bible, Speyr-Passavant offered copies of his publication to members of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres and asked them to examine the manuscript closely so that they would corroborate his theory. The support of Europe’s most renowned literary society would, as he wrote, certainly help him secure a buyer in France. Unfortunately, Dacier, who acted as the Académie’s Secrétaire perpétuel besides his appointment at the Bibliothèque royale, rejected his request with no explanation. In addition to scholars, Speyr-Passavant presented copies of his work to French ministers, hoping that they would revise their opinion and purchase the book; but again, their replies did not meet his expectations52.

Along with economic factors, reasons for these refusals were perhaps linked to new suspicions issued in Le Moniteur universel, on 11 December 1829, questioning the manuscript’s early date of production and the fact that Alcuin himself produced it53. Seeking favourable opinions from researchers to end these accusations, Speyr-Passavant asked, on 28 January 1830, Georges Bernard Depping, president of Société royale des antiquaires de France, to form a committee of experts, whose mission was to authenticate the Bible54. The commission included Jean La Bouderie, orientalist, the painter Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Jorand, Pierre-Nicolas Rolle, curator of the Bibliothèque de la Ville de Paris, and Jean-Baptiste-Bonaventure de Roquefort-Flaméricourt, historian and philologist. However, although they were not definitive and still confidential, their results, stating that Alcuin did not write himself the Bible, were released in Le Constitutionnel on 1 March 1830. Despite a statement published a few days later in the newspaper admitting that the article should not have been published before the final assessment, Speyr-Passavant, acknowledging his failure to sell the manuscript, returned to Basle in May 1830 after an eighteen-month stay in Paris55.

In the following years, Speyr-Passavant continued to collect comments from visitors, who examined the Bible, probably in his home Zum grünen Helm, where his collection was at least since 183456. Among them were the German poet Karl Baldamus, Anna Pavlovna at that time Princess of Orange, Johann Georg Schwarz, American consul in office in Vienna, and Willem Hendrik Jacob, Baron van Westreenen van Tiellandt, Dutch art- and book-collector57. In addition, Speyr-Passavant contacted potential buyers throughout Europe to offer them the Bible. His correspondents included Hippolyte de Châteaugiron, Marie-Nicolas-Silvestre Guillon, Dean of the Faculty of Theology at the Sorbonne and librarian of the Archbishopric of Paris, Guizot, who then served as Ministre de l’Instruction publique, Edward Harcourt, Archbishop of York, William Howley, Archbishop of Canterbury, Frédéric de Reiffenberg, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Louvain, as well as the book-collectors George John, second Earl Spencer, and Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex58.

Having perhaps received some positive responses, Speyr-Passavant travelled to England in January 1836, bringing the Bible with him. As he had spent some time in London, he knew that the long collecting tradition and wealthy book-collectors’ financial resources had made the city the new international centre of the antiquarian book-trade. Moreover, the fact that Alcuin was born in York also constituted a pertinent reason to market the manuscript in England. To help Speyr-Passavant during his stay, Franz Dorotheus Gerlach, curator of the Basle Öffentliche Bibliothek der Universität, and the Basle painter Hieronymus Hess produced recommendation letters, introducing him to librarians working at Cambridge, London, and Oxford, as well as to the London booksellers Koller & Comp.59.

Although the documentation on the stay in London did not entirely survive, comments in the Album reveal that Speyr-Passavant showed the Bible to specialists from early February 1836 onwards. Among them were curators of the British Museum, such as Sir Henry Ellis, principal librarian, Josiah Forshall, keeper of manuscripts, Madden, and William Young Ottley, keeper of prints and drawings, along with Bulkeley Bandinel, Bodley’s librarian. Other visitors included the book-collectors Philip Bliss and Alexander Douglas, tenth Duke of Hamilton, the dealer Robert Harding Evans, the antiquary Henry Petrie, and Joseph Romilly, Cambridge University administrator60.

According to Madden, who later published an article on the Bible in the Gentleman’s Magazine, Speyr-Passavant, apparently with the support of the Duke of Hamilton, first tried unsuccessfully to sell the volume to the Trustees of the British Museum; his offers started at £12,000, then decreased to £8,000 and finally £6,50061. After this vain attempt, he decided to auction the Bible on 27 April 1836. Robert Harding Evans, responsible for the sale, which took place in his shop in Pall Mall, prepared the catalogue containing 37 lots, including sixteen manuscripts and printed books, as well as additional works of art from Speyr-Passavant’s collection62. In it, the lot entry headed « The Emperor Charlemagne’s Bible » – probably compiled by Speyr-Passavant – spread over six pages. It opened with an account of Alcuin’s life in York and then in France and of his work on the manuscript. After that, the description focused on the book’s decoration, emphasizing the presence of Alcuin and Charlemagne in the second full-page miniature. Having provided information about Alcuin’s poem and the book’s provenance history, the entry then contained French and British scholars’ statements, confirming the manuscript’s authenticity, and concludes with an invitation exhorting an English book-collector or institution to acquire this « Inestimable Treasure ». This record, with the lengthy description of the miniatures, indicates once again that Speyr-Passavant exploited the decoration as a key selling point. It is also important to note that he adapted this catalogue record to the British clientele, mentioning that Alcuin was born in York, a pupil of the great English historian Bede the Venerable, and a preeminent representative of Anglo-Saxon literature.

Despite this detailed entry, Speyr-Passavant failed again to sell his Bible, as the press revealed the day after the sale63. Newspaper articles related that Evans, who conducted the auction, first stressed that this valuable manuscript should remain in the country. He then provided evidence for its early date of production and recounted Alcuin’s work for Charlemagne. Afterwards, he invited the assembly to bid for it, starting at £700; offers increased slowly until a certain Mr Siordet, merchant established at St Helen’s Place in London, eventually bought the lot for £1,500. This was a very disappointing result for Speyr-Passavant. Not only did he expect that the Bible would reach £2,500, he also had to secure a new buyer, for Siordet acted as his own agent64. The articles also stated that, to the attendees’ dismay, no representative of the British Museum bid for « that great national monument ». The fact that Josiah Forshall attended the auction and might have bought lot 16, a ninth-century manuscript, for the Museum, indicates that the Trustees undoubtedly considered the Bible too expensive a purchase65. In the following week, however, Forshall and Madden gathered additional information about the book to determine a new price66. At the same time, Speyr-Passavant planned to exhibit the Bible in the Cosmorama Rooms in Regent Street67. What happened next is hard to reconstruct precisely, but Speyr-Passavant eventually resolved to sell his manuscript for £750 to the Trustees in May 183668.

This outcome was not the high price that Speyr-Passavant had hoped for his Bible. It seems that the fourteen years, during which he spent an immense amount of time and energy to sell the manuscript, had exhausted him. In addition, he had invested considerable sums of money in his travels across Europe, his research, as well as publication on the book, and in the organisation of the auction by Evans. Furthermore, his explanations for proving the authenticity of the Bible had not convinced any purchasers. These reasons may well help understand why he eventually agreed to the British Museum’s offer.

It should, however, be noted that £750 equated to about 18,750 Swiss francs, therefore being an important sum comparing to the 288 or 480 Swiss francs that he paid for the manuscript in 182269. This increase in price shows that Speyr-Passavant proved to be a skilled dealer. The story of the « Moutier-Grandval Bible » has demonstrated that he developed a variety of sophisticated strategies to market his manuscript. As well as restoring its binding and leaves, Speyr-Passavant did a great deal of research on the Bible, by corresponding with renowned scholars and experts in medieval books and consulting the relevant literature and other Carolingian manuscripts, and published his findings in an essay. He also used the press to make the Bible known to the public and exhibited it in several cities. Finally, he presented it to numerous book-collectors throughout Europe and organised an auction for it.

This account has also revealed that Speyr-Passavant assigned new values to the Bible in order to sell it and, for this purpose, greatly exploited the decoration. Through its richly illuminated initials and miniatures, he managed to turn the manuscript into a luxury merchandise, requesting huge amounts of money for it. In addition, Speyr-Passavant’s numerous notes and letters, as well as his publication clearly demonstrate that his analysis, including that of the decoration, brought the volume into an international scholarly debate. His statements not only encouraged scholars to examine the manuscript, but also led some of the most distinguished historians and bibliographers of the nineteenth century, such as Hänel, Hug, Peignot, and Madden, to study it to determine its authenticity. Finally, Speyr-Passavant made the Bible a legendary book, written by an illustrious scholar for one of the most famous rulers of the Middle Ages and he succeeded to do so mainly through his interpretation of the second miniature, in which he recognised Alcuin and Charlemagne. Even though his analysis of the decoration was somewhat absurd, Speyr-Passavant managed to use it to assign the Bible aesthetical, financial, mythical, and scholarly values.

____________

1 See especially contributions in Johannes DUFT et al., Die Bibel von Moutier-Grandval: British Museum Add. Ms. 10546, Berne, Verein Schweizerischer Lithographiebesitzer, 1971; Joseph HANHART et al., La Grande Bible de Moutier Grandval, Basle, Heuwinkel, [1981]. See also David GANZ, « Mass Production of Early Medieval Manuscripts: the Carolingian Bibles from Tours », in The Early Medieval Bible: Its Production, Decoration and Use, ed. Richard Gameson, Cambridge, CUP, 1994, p. 53-62 (Cambridge studies in palaeography and codicology; 2).

2 Basle, Staatsarchiv des Kantons Basel-Stadt [hereafter Basle, SA], PA 207 9, non-foliated. I refer to these letters by providing their date of production. On these, see Johannes DUFT, « Die Geschichte », in J. DUFT et al., Die Bibel…, op. cit., [note 1], p. 45-48; Werner KAEGI, Jacob Burckhardt. Eine Biographie, Basle, Schwabe, 1947-1982, vol. 1, p. 246-250.

3 London, British Library [hereafter BL], Add. MS 10547. This document is paginated and foliated; to locate extracts from it, I indicate the number written on the leaves and specify whether it refers to a page (p.) or a folio (f.) number. On this, see Eva IRBLICH, « Das Album ADD. MS. 10547 », in J. DUFT et al., Die Bibel…, op. cit. [note 1], p. 187-193.

4 Johann Heinrich de SPEYR-PASSAVANT, Description de la Bible écrite par Alchuin de l’an 778 à 800, et offerte par lui à Charlemagne le jour de son couronnement à Rome, l’an 801, Paris, J. Fontaine, 1829.

5 Basle, Universitätsbibliothek [hereafter, Basle, UB], H IV 81a.

6 On him, see J. DUFT, « Die Geschichte », art. cit. [note 2], p. 42-43; W. KAEGI, Jacob Burckhardt…, op. cit. [note 2], p. 246-251. On his collection, see Johann Heinrich von SPEYR-PASSAVANT, Catalogue de la collection de manuscrits, tableaux, sculptures antiques, estampes et différents objets de curiosité dans les sciences et les arts qui composent le cabinet de J. H. de Speyr, l’ainé, Basle, J. G. Neukirch, 1835; Basle, UB, H IV 81 c, p. 11-18, 81-89 (two handwritten lists); Basle, SA, Gerichtarchiv PP 1.129, no. 176 (post-mortem inventory); Otto FISCHER, « Schweizer Altarwerke und Tafelbilder der Sammlung Johann Heinrich von Speyr in Basel », Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Jahresberichte 1928-1930, Neue Folge XXV-XXVII, 1931, p. 123-155; Otto FISCHER, « Nachträge zur Sammlung von Speyr », Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Jahresberichte 1931-1932, Neue Folge XXVIII-XXIX, 1933, p. 37-42.

7 Bonifatius FISCHER, « Die Alkuin-Bibeln », in J. DUFT et al., Die Bibel…, op. cit. [note 1], p. 63; Rosamond MCKITTERICK, « Carolingian Bible Production: The Tours Anomaly », in The Early Medieval Bible…, op. cit. [note 1], p. 71.

8 For these, see BL, Add. MS 10546, f. 349v-351r, 408v-409r.

9 For these, see BL, Add. MS 10546, f. 1v, 5v, 25v, 352v, 449r.

10 For analyses of the decoration, see Ellen J. BEER and Alfred A. SCHMID, « Die Buchkunst », in Die Bibel…, op. cit. [note 1], p. 121-185; Herbert L. KESSLER, The Illustrated Bibles from Tours, Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1977; Jean-Louis WALTHER, « Angelome de Luxeuil et la Bible de Moutier-Grandval (ixe siècle) », in Autour du Scriptorium de Luxeuil, ed. Philippe Kahn, Luxeuil-les-Bains, Association les Amis de saint Colomban, 2012, p. 76-151 (Les cahiers colombaniens; 2011).

11 J. DUFT, « Die Geschichte », art. cit. [note 2], p. 40; R. MCKITTERICK, « Carolingian Bible Production », art. cit. [note 7], p. 71-72.

12 For this inscription, see BL, Add. MS 10546, f. 449v. According to Albert Bruckner, the book’s binding was made in the sixteenth century probably in Basle, but no evidence in the archives of the Moutier-Grandval community helps establish whether it ordered it. On this, see Albert BRUCKNER, « Der Codex und die Schrift », J. DUFT et al., Die Bibel…, op. cit. [note 1], p. 99-100.

13 Ansgar WILDERMANN, « St. Germanus in Moutier-Grandval », in Die weltlichen Kollegiatstifte der deutsch- und französischsprachigen Schweiz, dir. Guy P. Marchal, Berne, Francke, 1977, p. 362-391 (Helvetia Sacra; II/2).

14 Auguste QUIQUEREZ, « Notice sur le chapitre de Moutier-Grandval établi à Delémont depuis 1534 », Actes de la Société jurassienne d’émulation, 14, 1864, p. 155-157; Auguste QUIQUEREZ, « La Bible d’Alchuin », Revue suisse des beaux-arts, 7, 1877, p. 17; Arthur DAUCOURT, « La Crosse de Saint-Germain », Actes de la Société jurassienne d’émulation, 15, 1908, p. 130-132; André RAIS, « La Bible de Moutier-Grandval », Actes de la Société jurassienne d’émulation, 38, 1933, p. 169.

15 Jean-Louis RAIS, « La Bible de Moutier-Grandval retrouvée et vendue il y a 200 ans: par qui ? Où ? Quand ? Pourquoi ? », Actes de la Société jurassienne d’émulation, 117, 2014, p. 175-184.

16 Jacob BURCKHARDT, Briefe. Vollständige und kritisch bearbeitete Ausgabe, ed. Max Bruckhardt, Basle, Schwabe, 1949, vol. 1, p. 49-52; J. DUFT, « Die Geschichte », art. cit. [note 2], p. 48.

17 This is known from a copy of the description that Speyr-Passavant transcribed in the Album. For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 13v.

18 For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 13v.

19 For this, see Basle, SA, PA 207 9, 18 April 1822. This archival file also contains undated transcripts and translations of the poem and epigrams, very likely written by Burckhard.

20 Speyr-Passavant probably had access to the handwritten chronicle through Bennot, according to the sale agreement.

21 For this, see Basle, SA, PA 207 9, 7 September 1822.

22 On the Abbey’s coat of arms, see Betram RESMINI, « Prüm », in Die Männer- und Frauenklöster der Benediktiner in Rheinland-Pfalz und Saarland, ed. Friedhelm Jürgensmeier with the collab. of Regina Elisabeth Schwerdtfeger, St. Ottilien, Eos, 1999, p. 649 (Germania Benedictina ; 9).

23 For this, see Basle, SA, PA 207 9, undated.

24 For this, see Basle, SA, PA 207 9, 23 January 1823.

25 J. H. de SPEYR-PASSAVANT, Description…, op. cit. [note 4], p. 4-7.

26 Evidence for this is provided by subsequent documents. For these, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 48r, 65r.

27 This is known from a letter sent to Burckhardt. For this, see Basle, SA, PA 207 9, 23 November 1822.

28 Johann Leonhard HUG, Einleitung in die Schriften des Neue Testaments, Tübingen and Stuttgart, Cotta, 1826, p. 476-480.

29 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France [hereafter BnF], ms. Lat. 1; Rome, Abbazia di San Paolo fuori le mura, no catalogue number.

30 For these, including Hug’s essay annotated by Speyr-Passavant, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 2r-38v, 41r-42r.

31 For his signature, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 39r.

32 For their signatures and comments and those of other visitors, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 39r-40v.

33 For their comments, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 40v.

34 Evidence for this is provided by the copy of a letter he wrote to Rayneval in March 1829. For this, BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 64v-65r.

35 For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 43v.

36 Johann Leonhard HUG, « Kritisch-diplomatischer Bericht über eine Handschrift der lateinischen Übersetzung des alten und neuen Testamentes nach Alkuins Ausgabe », Zeitschrift für die Geistlichkeit des Erzbisthums Freiburg, 2, 1828, p. 1-67. This article was published after 14 November 1828, since new book-censors in the archiepiscopacy of Freiburg im Breisgau were appointed that day as detailed in the section « Beförderungen » of the journal (p. 295).

37 For their comments, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 44r-46v, 48v.

38 For a copy of this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 46v-48r.

39 For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, p. 49, f. 51r.

40 For the letters Speyr-Passavant exchanged with government representatives and Dacier, see BL, Add. MS 10547, p. 50, f. 52r, p. 54, f. 55r-56r, 62r, 63r, 64v-67r, p. 75-78.

41 For their correspondence with Speyr-Passavant, see BL, Add. MS 10547, p. 79-81, 95-96, f. 173r, p. 189.

42 For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, p. 57-61.

43 BnF, ms. n.a.l. 1203.

44 Peignot’s contributions, « Lettres à M. C.-N. Amanton sur deux manuscrits précieux du temps de Charlemagne », were issued in J. H. de SPEYR-PASSAVANT, Description…, op. cit. [note 4], p. 79-104.

45 For their letters, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 111r-113v, 115r-118r.

46 For copies of the review, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 139v-140r.

47 Gustav Friedrich HÄNEL, Catalogi librorum manuscriptorum, qui in bibliothecis Galliae, Helvetiae, Belgii, Britanniae M., Hispaniae, Lusitaniae asservantur, Leipzig, J. C. Hinrichs, 1829-1830, cols 281-282 (for the description of the Bible), 660 (for Speyr-Passavant’s collection in Basle).

48 For copies of these, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 151r, 154r.

49 Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana, ms. B 6.

50 In a supplement to Description de la Bible écrite par Alcuin, published after 14 April 1830, Speyr-Passavant added twenty supplementary statements, including those of François-René de Chateaubriand, author and politician, Alexandre Lenoir, administrateur des monuments de l’église royale de Saint-Denis, and Mathieu-Guillaume-Thérèse Villenave, former Professor of history at l’Athénée royal. For these and further comments, see J. H. de SPEYR-PASSAVANT, Description…, op. cit. [note 4], p. 105-118; BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 156r-v, 164v, p. 167, f. 168r, 173v, 210r, 219v-220v, 223r, 230v-231r, 232r, 234r-235v. The date of publication of the supplement is provided by the copy of a letter sent by Father Stanislas-Barnabé Trébuquet to Speyr-Passavant on 14 April 1830 (p. 118).

51 For this quotation, see J. H. de SPEYR-PASSAVANT, Description…, op. cit. [note 4], p. 78.

52 For these letters and copies of these exchanged with Dacier and members of the government from late October 1829 to late April 1830, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 168v-169v, 170v-173r, 175r-176r, p. 181-185, 187-188, 190-192, f. 194r-196r, 198r, 203r, p. 204, 206-207, f. 211r-212r, f. 222r, f. 229v, p. 236.

53 For this and subsequent articles, including Speyr-Passavant’s replies issued in December 1829 in Le Moniteur universel, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 196r, 197v, 198v, 199v, 202v.

54 For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 219r.

55 For this article and the statement, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 225r, 229r.

56 J. DUFT, « Die Geschichte », art. cit. [note 2], p. 42.

57 For their statements and those of further visitors, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 240v, 243r, 245r, 254r-255v, 257v, 259v. The visits of Anna Pavlovna and Van Westreenen are known from the copy of a letter that Speyr-Passavant sent to the Princess’ Secretary. For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 251v, 255r-v, 257r.

58 For copies of his letters, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 245v-251v; Basle, UB, H IV 81a, f. 8v, 12v-13r. Reiffenberg saw the Bible at Paris as shown by his comment in the Album. For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 134v-135r. Having heard of his collection of biblical works, Speyr-Passavant had already unsuccessfully offered his manuscript to Prince Augustus Frederick in December 1829. For this, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 201v.

59 For these and further copies of recommendation letters, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 260r; Basle, UB, H IV 81a, f. 21r-23v.

60 For their comments, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 261r-263v.

61 Frederic MADDEN, « Alchuine’s Bible in the British Museum », Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. VI, New Series, 1836, p. 358-363 (Oct.), p. 468-477 (Nov.), p. 580-587 (Dec.). In this article, Madden reported that « much correspondence [concerning the sale] took place », but Speyr-Passavant kept no record of these letters as he did at Paris. On Madden’s work on the Bible, see J. DUFT, « Die Geschichte », art. cit. [note 2], p. 34-36; Alan Noel Latimer MUNBY, Connoisseurs and Medieval Miniatures, 1750-1850, Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 1972, p. 154-155. The Duke of Hamilton’s participation is known from the draft of a letter that Speyr-Passavant addressed to his sons. For this, see Basle, UB, H IV 81a, f. 25r-27r.

62 Robert Harding EVANS, Catalogue of Manuscripts, Books and Prints, Paintings and Carvings, the Property of M. de Speyr Passavant, London, 27 Apr. 1836. For a copy of this annotated by Madden, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 267r-272v.

63 See for example The Globe and Traveller, 28 April 1836, p. [3]; The Times, 28 April 1836, p. [3]. For an article from Bell’s Life in London, 1 May 1836 in the Album, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 272v. European newspapers also reported the auction. See for example, Das Ausland, 16 May 1836, p. 547; Der Schweizer-Bote, 11 May 1836, p. 151; Le Constitutionnel, 2 May 1836, p. [3].

64 For Speyr-Passavant’s previous contacts with Siordet, see Basle, UB, H IV 81a, f. 26r.

65 The other item, containing Jonas of Orléans’s De institutions laicali and his Epistola Concilii quisgranensis ad Pippinum Regem Directa, is now BL, Add. MS 10459.

66 A. N. L. MUNBY, Connoisseurs…, op. cit. [note 61], p. 154.

67 For the exhibition leaflet and booklet, see BL, Add. MS 10547, f. 273r-277v.

68 F. MADDEN, « Alchuine’s Bible… », art. cit. [note 61], p. 363.

69 This rough calculation is based on the article in Der Schweizer-Bote, mentioning that Siordet bought the manuscript for 37,500 Swiss francs.