William Morris’ Medieval Manuscript Collection and the Trade in Illuminated Manuscripts

c. 1891-1914

The research for this article has been undertaken as part of the CULTIVATE MSS project, which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 817988). I am grateful to the staff at Bernard Quaritch Ltd., the British Library, the Bodleian Library and the Huntington Library for their help in accessing archival materials and to Federico Botana, Natalia Fantetti, Danielle Magnusson, Hannah Morcos, Pierre-Louis Pinault, Angéline Rais, and William P. Stoneman for discussion of the ideas presented here.

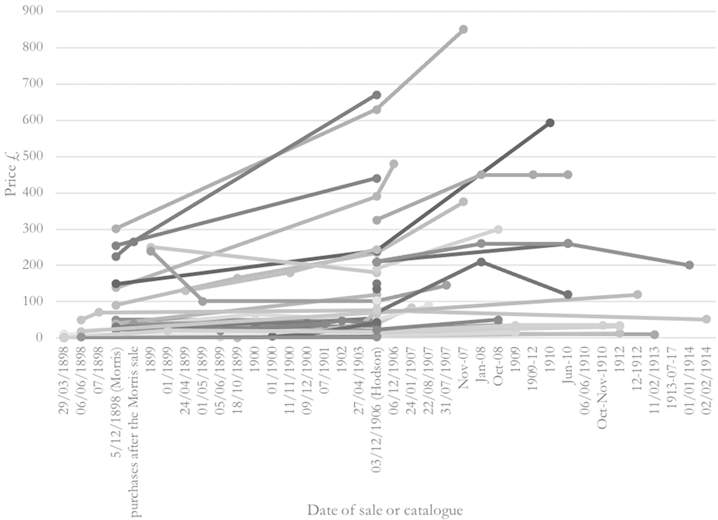

« It is not an every-day occurrence that a library dispersed at Sotheby’s represents the tastes of a collector who was at once a distinguished poet, an artist, a socialist, a leading light in decorative production, and a reviver of ancient typography, illumination, and varied branches of book-lore »1. Thus observed the London Daily News reporting on the sale of part of William Morris’ library in December 1898. Morris’ collection included medieval manuscripts and early printed books and has attracted attention as part of studies of Morris’ artistic endeavours and his work with the Kelmscott Press2. In addition, Morris’ acquisition of manuscripts and the immediate fate of his library after his death on the 3rd of October 1896 have been well studied, notably by Paul Needham and Michaela Braesel3. That work provides a foundation for an analysis of the place of the manuscripts acquired by Morris within the trade in manuscripts between c. 1891, when Morris began collecting in earnest, and the outbreak of the First World War, which disrupted the international book trade, in 1914. The potential for books and manuscripts to increase in value was noted in reports of the 1898 sale, with attention drawn to high prices and individual volumes that had sold for significantly more than Morris had paid for them a few years earlier. Moreover, the recurrence of Morris’ name in later accounts of the manuscripts suggests that his ownership was considered to make them more desirable. The subsequent career of Sydney Cockerell, who worked for Morris from 1892, helped some of Morris’ manuscripts maintain a high profile, as their connection with Morris was reiterated in Cockerell’s work4. Yet an analysis of the prices asked and paid for the manuscripts owned by Morris between c. 1891 and 1914 reveals broader trends in the market and suggests that although manuscripts valued at relatively high prices in the 1890s increased significantly in value over the following two decades, there was much less change at the bottom of the market. It also demonstrates that Morris’ manuscripts were not a lucrative short-term investment for collectors, although as the bookseller James Tregaskis observed in 1901, « with a little good will […] another and more valuable appreciation of their worth will grow as time passes by »5. In all this, the fate of Morris’ collection does not appear to have been as exceptional as Morris himself.

The creation of Morris’ library can be reconstructed from a series of catalogues, together with his correspondence6. A catalogue of c. 1876 included six medieval manuscripts, only two of which reappeared a list of 1890-17. In c. 1876 Morris owned two Bibles (now London, Society of Antiquaries MS 956 and Philadelphia, Free Library MS Lewis E 36), a thirteenth-century life of Saint Denis, an early fourteenth-century copy of Aristotle’s Physics, Xenophon’s De legibus Lacedaemoniorum, and Prolianus’ Astronomia (now Manchester, John Rylands Library MS Ryl. Lat. 53)8. The 1890-1 catalogue, annotated by Cockerell with the information that it was begun by Morris’ daughter Jenny and continued by Morris, also included six medieval manuscripts9. In addition to the two Bibles from the earlier list, these were Poggio Bracciolini’s De varietate fortunae (now Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Buchanan d. 4), Peraldus’ Summa de vitiis et virtutibus, a collection of romances bought from J. & J. Leighton in 1890 (now Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS McClean 179), and « A list of Abbies [sic.] and Churches etc. ». In both 1876 and 1890, these manuscripts were exceptions in a library dominated by early printed books.

Morris’ interest in manuscripts in the 1890s developed in conjunction with his work on the Kelmscott Press, and The Times later claimed that « he accumulated the majority of his books with a definite purpose – viz., to assist him in his highly-laudable object of improving the art of typography »10. Morris’ purchases were facilitated by Bernard Quaritch, who was advertising and distributing the Kelmscott books, and the firm J. & J. Leighton who were also binding books for Morris11. Between 1891 and 1896 Morris bought at least twenty-nine manuscripts through Quaritch and twelve through Leighton. Some of these purchases were from the booksellers’ stock, but Morris also placed commissions for items at auction. His bids were not always successful. After the auction of the seventh portion of the Phillipps collection in March 1895, for which Morris had left three commission bids with Quaritch, Morris wrote to his friend the retired bookseller Frederick Ellis explaining that the manuscripts he wanted had sold for much higher prices than he had bid12. He declared « Rejoice with me that I have got 82 MSS., as clearly I shall never get another », a fear that was unfounded as he obtained about thirty more before this death seventeen months later, including one at the next Phillipps sale in 189613.

There are hints in Morris’ letters that he thought of library as an investment that could be realised by his family through the sale of the collection after his death14. In 1896, following the purchase of a bestiary from Jacques Rosenthal for £900 (the highest price Morris had paid for a manuscript to date), he wrote: « it will certainly fetch something when my sale comes off »15. The idea of his temporary ownership may also have helped Morris resolve the paradox of a prominent socialist amassing a private collection of expensive books. In 1891 he had justified his collection of early printed books on the grounds that :

if we were all Socialists things would be different. We should have a public library at each street corner, where everybody might see and read all the best books, printed in the best and most beautiful type. I should not then have to buy all these old books, but they would be common property, and I could go and look at them whenever I wanted them, as would everybody else. Now I have to go to the British Museum, which is an excellent institution, but it is not enough. I want these books close at hand, and frequently, and therefore I must buy them16.

By the time Morris died in October 1896 there had been little chance for the market to rise and provide an improvement on the prices that he had paid. Nevertheless, preparations were immediately made for the sale of the library by Morris’ executors; Jane Morris, Ellis and Cockerell, and Ellis quickly produced a valuation of the books and manuscripts17. This document is now in the Huntington Library, and includes 113 unique entries in the section for manuscripts, of which 110 appear to be medieval European books18. A note added to the list by Sydney Cockerell claims that « The prices fixed were as near as possible those paid by Morris »19. The manuscripts’ total value was estimated at about £12,50020.

The posthumous list did not, of course, feature manuscripts that Morris had parted with in his lifetime. In addition to four of those from the 1876 catalogue, these included a Psalter (now New York, Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Western MS 38) inscribed to his daughter Jenny in a note dated January 17 1892 (her birthday) and an Antiphoner given to Robert Steele, for whom Morris also wrote a preface for Steele’s work on Bartholomew de Glanville21. Another manuscript missing from the list was the Pabenham-Clifford (or Clifford-Grey, or Grey-Fitzpayn) Hours (now Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS 242), as Morris had made arrangements for this to go to the Fitzwilliam Museum as part of an agreement through which leaves from the manuscript held by the Museum had been reinserted into the book22. Cockerell delivered the manuscript to Cambridge (his first visit to the city) on the 22nd October 189623.

The executors attempted to sell the rest of the library as a collection (although Morris’ will allowed his wife to keep items she wanted)24. Morris’ friend, the artist and dealer in art and books, Charles Fairfax Murray made arrangements to purchase the collection for £20,000, but by 21 January 1897 this had fallen through25. Over the next three months the library was shown to collectors and dealers26. In March 1897 Quaritch produced a list entitled The Best Books in the Library of William Morris, including 75 manuscripts, already hinting at the possibility that the collection might be broken up27. Yet in April, Pickering & Chatto arranged to buy the library on behalf of Richard Bennett for £18,00028. The firm charged Bennett a further £2,000 in commission. In 1898 Henry Wheatley rejoiced « It is fortunate that a collection made by one who knew so well what to buy is not to be dispersed or taken out of the kingdom. As long as it remains intact it will be a worthy monument of an enthusiastic lover of art who, while teaching the present age, was not forgetful of the history of the earlier workers in the same spirit »29. He had, however, spoken too soon.

Cockerell’s diary for 1899 includes Bennett’s name, with the address « Summer Hill, Pendleton »30. This enables Bennett (1849-1930) to be identified in census records as a bleacher of calico and chemical manufacturer. In 1900 a catalogue of Bennett’s early printed books and manuscripts was published, which listed 106 manuscripts and two miniatures31. On the basis of this, Bennett’s interest seems to have focused on heavily illuminated devotional books. The list includes 51 Books of Hours (mostly identified as having been made in France in the fifteenth century) together with seventeen Psalters, seven Missals, three Breviaries and three « Officium B.M.V. » Exceptions to this interest in devotional works included three copies of the Roman de la Rose. In 1902 Bennett sold his collection to the American banker J. P. Morgan, and it was recatalogued as part of Morgan’s growing collection by M. R. James, in another, much more detailed, catalogue published in 190632. That catalogue proclaimed the manuscripts’ association with Morris and Bennett as part of its title, and books owned by Morris were identified in the « List of Manuscripts » at the start of the volume.

The Morgan catalogue identified thirty manuscripts as having some from Morris via Bennett33. A further 79 manuscripts were sold at auction in December 1898 as « a portion of the valuable collection of Manuscripts, Early Printed Books, &c. of the late William Morris », with no reference to Bennett34. The Times observed « However much one may regret the dispersal of a library so thoroughly characteristic of the founder as that of the late William Morris, it is better that such a large number of exceedingly beautiful books should be scattered than that it should be absolutely inaccessible to students and collectors generally »35. The sale included 1215 lots and recouped £10,992 11s of Bennett’s £18,000 (before the deduction of Sotheby’s charges). The brief descriptions in the 1896 valuation list make it difficult to identify some of the Bibles and Books of Hours with certainty, although later annotations by Cockerell, including the numbers used in James’ 1906 catalogue, provide a guide to what he thought became of them. With this caveat, it appears that the manuscripts retained by Bennett in 1898 had, in general, been assigned high financial values in 1896, probably representing £7,889 of the £12,500 valuation in the 30 manuscripts later sold to Morgan36. Notable exceptions to this pattern were Bennett’s decision to keep a « Manuale » attributed to Augustine, dated 1462, with a richly decorated first page, which had been valued at just £3, and a fifteenth-century manuscript containing an adaptation of the Psalms attributed to Bonaventure, valued at £3637. Equally, he sent some religious manuscripts that had been highly valued in 1896 to auction, including the Sherbrooke Missal (valued at £200) and five thirteenth-century Bibles each valued at £100 or more38.

The 1896 valuation had been based on the prices Morris paid for books, with some attempts to adjust « bargains » to what were believed to be current market prices39. The sale of the manuscripts two years later demonstrated the challenge of predicting the results of an auction. The sale included 79 manuscripts dated to between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries. Nine of these sold for £100 or more and a further twelve raised over £50. At the other extreme, ten manuscripts raised less than £10. Although the press coverage of the sale focused on high prices paid for individual manuscripts and described the sale as a success, the Western Daily Press claiming that « On all hands one hears the remark that it constitutes as record sale », altogether the manuscripts raised £4,303, slightly less than the £4,611 that would have been the remaining portion of the 1896 valuation40. Cockerell’s observation of the first day of the sale : « prices fairly good but not extraordinary by any means », therefore seems an accurate assessment41. Yet, that the manuscripts had largely held their value was noteworthy. In April 1898 newspapers reported on the very low prices paid for Harold Baillie Weaver’s books, another collection formed in the 1890s. Several papers ran an article that declared « Speculators in rare books may learn a lesson from the history of the books and manuscripts, the property of Harold Baillie Weaver, Esq., which were sold at Christie’s the other day. The collection of 528 lots was purchased in 1895 for upwards of £25,000 at the Philli[p]ps, Gennadius and Stuart sales ; but it now realised only £5,527! »42. The Times concluded that the books had been « for the most part bought at sums much beyond a reasonable market value », but that « they have now been sold at the other extreme »43.

Of the 79 manuscripts auctioned by Bennett in 1898, 73 can be confidently identified in the 1896 valuation list. Among those that raised considerably more than their 1896 valuations was lot 732, a copy of Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews valued at £210, which Quaritch bought for Robert Hoe for £30544. The price was particularly remarkable because the sale catalogue included the fact that the manuscript had been sold in 1895 for £200, but Hoe had been prepared to spend up to £400 to secure the volume45. A twelfth-century manuscript in its original binding (lot 580), valued at £100 (which had been bought by Morris at the Phillipps auction of 1896 for just £13), was bought by Henry Yates Thompson for £18046. Another high price noted in the reporting was Yates Thompson’s purchase of the Sherbrooke Missal (lot 903), valued at £200, for £35047. Yates Thompson was a well-known collector, who aimed to build a small collection of what he deemed the best manuscripts48. He had purchased the « Appendix » collection from the Earl of Ashburnham in 1897, but sent most of the manuscripts to auction in 1899, echoing Bennett’s treatment of the Morris library. The prominence of collectors like Yates Thompson at the Morris sale in achieving high prices, either through commissions or in person, is probably also due to the operation in this period of « the Ring »; the dealers’ practice of keeping prices low in the auction room and splitting their profits through a second auction immediately after the sale49. Since these prices were not generally recorded it is difficult to assess the impact of this activity, though it may be reflected in the prices at which dealers subsequently advertised manuscripts.

One reporter attributed the high prices overall at the Morris sale to « the spirited bidding of the gentleman who is said to be buying for America »50. An American resident in London, Henry Wellcome, was bidding under the pseudonym Hal Wilton, but did not export the manuscripts he obtained or pay high prices51. Benjamin Franklin Stevens, who did buy for American collectors, bought only one manuscript (lot 365), a Cicero, for £32, which was subsequently in the collection of the American Robert Hoe. Quaritch had two commission bids for Hoe, both of which he secured: lot 732 (the Josephus) and lot 694 (Onasander) for which Hoe had been prepared to spend £250, but which was obtained for just £2352. Another of Quaritch’s purchases, a glossed volume of the biblical books of Kings, also found its way to an American shortly after the sale. Carl Edelheim, originally from Germany, but a naturalised USA citizen based in Philadelphia, owned the manuscript before his death on 28 September 1899. His library was sold in New York the following year, where the manuscript, with its Morris provenance noted, raised only $47.5053. The exchange rate in this period was a little under $5 to the £1, so a generous conversion would make the book worth £10 at this sale54. This compares with the £31 paid by Quaritch in 1898 and £25 recorded in the 1896 valuation. The manuscript therefore proved a very poor short-term financial investment.

While it is possible that the gentleman invoked by the press wanted printed books, at this sale very few manuscripts appear to have been bought « for America »55. Yet the concern about the export of manuscripts resurfaced in the press in 1902, when the sale of Bennett’s collection to Morgan was made public (albeit with Morgan’s identity omitted). The Times lamented « Can nothing be done to stem the continuous and wholesale exportation of rare early printed and other books and illuminated MSS. to the United States of America? The “drain” has been going on for over half-a-century; within recent years it has reached huge proportions »56. The correspondent suggested that Morgan’s purchase might be the « most important single transaction which has occurred – or, perhaps, is likely to occur », an idea that was to prove overly optimistic as more libraries were sold in the following decades. However, the article concluded that « if English collectors will not avail themselves of such unique opportunities, it is, at all events, comforting to reflect that, as in the present instance, the collection is in the custody of an English-speaking nation ». This is a striking statement of an idea about a shared culture based on language, particularly given that manuscripts in Europe were, in general, easier for those based in Britain to access. However, it is a reminder that manuscripts were also traded with European dealers in this era, just as Morris had purchased his Bestiary from Rosenthal, sending Cockerell to collect it from Munich57.

Although in 1898 some manuscripts sold for more than Morris had paid for them, many sold for less than their 1896 valuation. The abundance of thirteenth and fourteenth-century Bibles probably helped keep prices for those items modest, potentially aided by the activities of « the Ring ». Bennett had retained two Bibles (valued at £650 and £100). The other twelve originally complete Bibles included in the auction had been valued at between £5 and £200 each, with a combined total of £1054 10s, but they achieved only £819, even with one lot (170), bought for £190 in 1894, that sold for £30258. Similarly, while one, thirteenth-century, copy of Gratian’s Decretum with thirty-seven historiated initials (lot 558) sold for more than its 1896 valuation of £180, bought by Quaritch for Laurence Hodson for £255, four other copies all sold for less than their earlier valuations. In three cases the decrease was between £1 and £3, and by the time a dealer’s commission was added the prices for buyers would be very close to the 1896 estimates. However a glossed copy of the Gospels of Luke and John that had been bought by Morris in 1896, having been advertised by Quaritch for £30, was valued after his death at £25, and sold for just £10 10s in 1898. This example is particularly striking because Leighton sold the manuscript on to Alfred Higgins immediately after the sale for £25, suggesting that in this case the 1898 sale price was usually low.

The 1898 sale attracted dealers and collectors, and newspapers reported « a large attendance of buyers »59. Quaritch’s name appears as the most frequent buyer of manuscripts and largest spender (purchasing twenty-one lots for £1,892), but eleven of these purchases were commissions. Quaritch’s appraisal of the collection in 1897, together with commission bids, probably added to his confidence that particular manuscripts would find buyers, and some volumes were bought for stock, with six of the manuscripts appearing in a catalogue dated February 189960. Leighton bought eleven manuscripts for £519 (including three commissions), and Pickering & Chatto, who had organised the sale of the manuscripts to Bennett, seven Bibles for £382. There seems to have been no special effort by either Quaritch or Leighton to buy back manuscripts they had sold to Morris. This occurred in at least seven cases for Quaritch, but six of these were commissions.

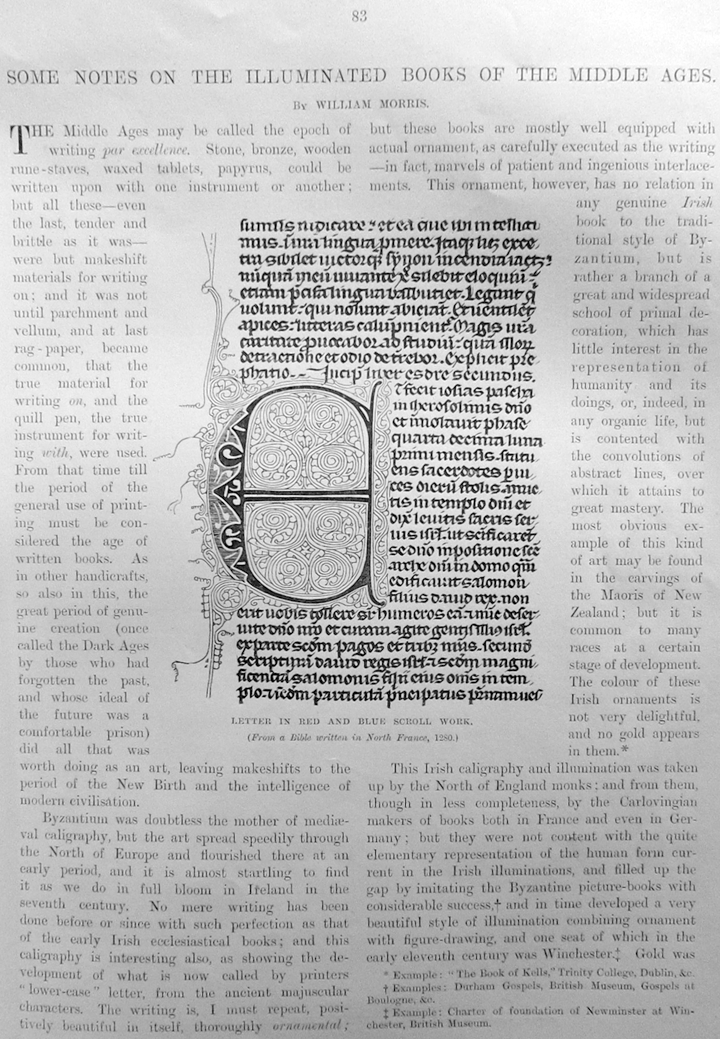

Two of the Bibles bought by Pickering & Chatto appeared in a catalogue they issued in 190061. That catalogue also included six manuscripts sold in 1898 where the buyer was not recorded as Pickering, suggesting either that manuscripts changed hands between dealers at or shortly after the sale, or that Pickering continued to buy manuscripts associated with Morris62. In Pickering’s 1900 catalogue, these eight manuscripts were all identified as being from « the library of William Morris ». Moreover some of the entries contained information suggesting what Morris had thought about a book. For example, the entry for one Bible declared that « A number of pages have been torn but have been sewn together with coloured silks in a most satisfactory manner. This piece of handy-work was a source of great satisfaction to the late William Morris: in fact the careful mending may have had something to do with his purchase of this book »63. In the entry for another Bible the author speculated « We should imagine that this book appealed to William Morris more for its pen letters than for its illuminations »64. The former is now in London, Society of Antiquaries MS 956. The latter was sold to the Boston Public Library by Cockerell in December 1900, where it is now MS f. Med. 165. That it had indeed been valued for its penwork is suggested by the use of an image of one of the pen-flourished letters in an article by Morris entitled « Some Notes on the Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages », published in 1893 [ill. 1]66.

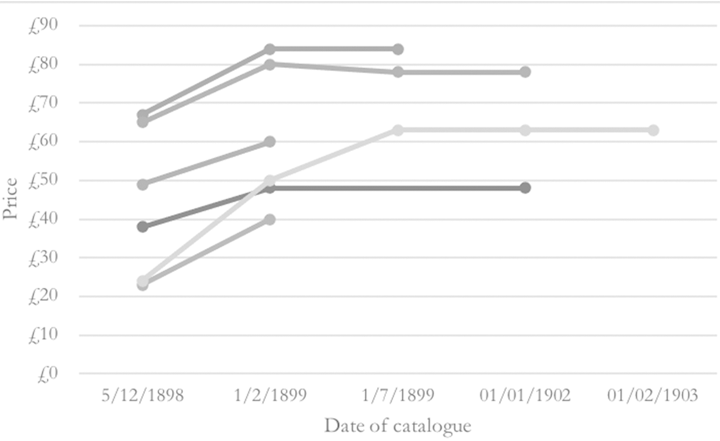

Quaritch was quick to include purchases at auction in catalogues, and his February 1899 catalogue (No. 186) was entitled Catalogue of Rare & Valuable Books from the libraries of William Morris, Lord Ashburnham, and the Revd. Makellar. Unlike Pickering, however, in Quaritch’s catalogue the individual entries were not explicitly identified with Morris (with the exception of catalogue no. 7, four leaves from a Missal). Nevertheless, six of the manuscripts bought by Quaritch at the 1898 sale can be identified in the February catalogue. Two of the manuscripts presumably sold quickly as they do not reappear in Quaritch’s catalogues. These were a Book of Hours offered by Quaritch for £60 (having been purchased in 1898 for £49 (lot 487)) and a copy of Gregory IX’s Decretales (purchased for £23 in 1898 (lot 513)), offered for £40. The latter was probably bought by Hodson as it was included in his sale in 1906. Three of the manuscripts purchased by Quaritch at the Morris sale, all copies of Gregory IX’s Decretales, reappeared in a second catalogue in July 1899, but from this point their connection to Morris was no longer noted67. Instead they were incorporated into a list of seventeen manuscripts advertised as « illuminated and decorated mediaeval manuscripts on vellum. From the famous Ashburnham Library, and the Collection of M. Henriques de Castro of Amsterdam ». Quaritch’s method seems thus to have been to trade on the idea of recent purchases as fresh stock, without considering Morris’ ownership particularly important. One of the copies of the Decretales (lot 561, £67 in 1898) was offered for £84 in July 1899. It was presumably sold soon after, as it does not reappear in Quaritch’s catalogues and in 1908 it was lent by Bruce Ingram to the Burlington Fine Arts Club exhibition68. The remaining three manuscripts, two copies of the Decretales and a commentary on the same, remained in stock [ill. 2].

Quaritch died on 17 December 1899, and his son Bernard Alfred Quaritch continued the business. In addition to listing recent purchases, from 1900 the company produced a series of thematic catalogues, with the result that the unsold Morris manuscripts were not relisted until 1902, when the firm published A Catalogue of Ancient, Illuminated & Liturgical Manuscripts Ranging from the viith to the xviiith Century, Facsimiles of MSS. and of Books Illustrating the Science of Palaeography, including three of the purchases from the Morris sale. As in the July 1899 catalogue, in 1902 the Morris provenance was not mentioned. A copy of the Decretales (lot 563, £65 at the 1898 sale), was offered for £80 in February 1899, before being reduced to £78 in July 1899 and 1902. It was sold by Sotheby’s in 1909, who noted Morris’ Kelmscott Book label, when the volume fetched just £50. Giovanni d’Andrea’s Novella sive commentarius in decretales epistolas Gregorii IX, bought by Quaritch for £38 in 1898 and offered for £48 in February 1899 did not reappear in the catalogue of July that year. However, it stayed in Quaritch’s stock and was relisted in 1902, again for £48. It reappeared in a Quaritch catalogue of February 1911 (no. 874), where its Morris provenance was noted, and it was then offered for £60. It is unclear whether the manuscript had remained in Quartich’s stock during this time or been sold and reacquired. It was offered at Sotheby’s in 1912, where it was listed as being bought by Quaritch for £50, which could have been an attempt by Quaritch to dispose of a manuscript that had been in stock for fourteen years69. Another copy of the Decretales (lot 560, £24 in 1898) was offered by Quaritch for £50 in February 1899, and then for £63 in July of that year. It reappeared in Quaritch’s catalogues in 1902 and 1903, again offered for £63, and by 1909 was in the hands of Tammaro De Marinis, who listed it as sold. In De Marinis’ catalogue the manuscript’s Morris provenance was noted through the quotation of the ex-libris « From the Library of William Morris Kelmscott House Hammersmith »70.

Ill. 1. Illustration from one of the Bibles owned by William Morris. « Some Notes on the Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages », The Magazine of Art, 17, 1893, p. 83.

Ill. 2. Prices of manuscripts bought by Quaritch for stock in 1898 and their valuations in the firm’s catalogues.

The eleven manuscripts bought by Leighton at the 1898 sale demonstrate the different amounts of profit achieved through commissions and sales, as well as from different clients and on different manuscripts. At the sale Leighton held bids for manuscripts from Charles Butler (director of the Royal Insurance Company, a collector of rare books and paintings, and a regular client of Leighton’s) and Nathaniel Evelyn William Stainton71. Stainton obtained two manuscripts (lots 34 and 78) for a total of £50 and a commission of 10 %. Leighton bought lot 71, an Aristotle, for Butler who paid the sale price plus commission. Butler bought a second manuscript, lot 972 (a Psalter), on the day after its auction. Leighton made a good profit on this manuscript, which he bought for £85 and sold to Butler for £105. Leighton achieved several other quick profits. Frank McClean, an astronomer and collector, purchased the collection of romances from Leighton during the sale, paying £100 for a manuscript Leighton had bought for just £69 (lot 988) and which had been valued at £52 in 189672. Alfred Higgins bought two manuscripts from Leighton on the day after the conclusion of the sale73. A volume of statutes that had been valued at £42 in 1896, sold at auction for £40, and was bought by Higgins for £45. The Glossed Gospels valued in 1896 at £25, was bought by Leighton for just £10 10s, and was then sold to Higgins for £25. On the 20th December Allan Francis Vigers, an architect and designer whose work was strongly influenced by Morris, bought a metrical Latin Grammar that Leighton had obtained for £5 10s for £10. Having placed his commission bids with Quaritch, Hodson also obtained two manuscripts from Leighton apparently soon after the sale. Leighton’s stock book suggests that Hodson bought lot 470 (which sold for £27 10s at the auction) for £38 and lot 1155 (which sold for £225 at auction) for £265. Leighton, therefore, did very well out of the Morris auction, and their records also indicate the close relationship between dealers, as in May 1900 they sold a Missal that had been advertised for £25 in Pickering’s 1900 catalogue (having sold for £19 in Morris’ sale) to the Royal Library of Belgium for £2874.

Of the collectors who bought in person at the sale, Yates Thompson spent the largest sum (£549), but bought only three manuscripts (lots 580, 745, 903). For all these manuscripts he paid considerably more than their 1896 valuations, with lot 580 valued at £100 and sold for £180, lot 745 valued at £6 10s fetching £19, and lot 903 valued at £200 sold for £350. In contrast, Wellcome bought ten manuscripts for £176 9s as well as buying printed books75. Where the 1896 valuations for these manuscripts can be identified they are very close to the sums Wellcome paid for them at the sale. Wellcome, who made his fortune through his pharmaceutical business, is now known as a collector of material about medicine, but at the Morris sale he bought a Book of Hours (lot 439), two Psalters (lots 815 and 867), a New Testament (lot 1023), Peraldus’ Summa de vitiis et virtutibus (lot 932), a chronicle (lot 930)76, an « Alphabetical Catalogue of European Monasteries and their Possessions » (lot 904 and the list of abbeys referred to in Morris’ 1890/91 list), Peter Riga’s Aurora (lot 862), Justinian’s Code (lot 736), and a book of decretals and statutes of the Cistercian order from the monastery of St Salvatoris, Antwerp (lot 662). Thomas Buchanan, Member of Parliament for Edinburgh, bought three fifteenth-century Italian manuscripts for £50 12s. These were Leonardus Aretinus, Historiarum Florentini populi libri XII (lot 131, £25), De Romanorum magistratibus attributed in the 1898 sale to Fenestella (lot 297, £13), and Poggio Bracciolini’s De varietate fortunae (lot 863, £12 12s). In the cases of lots 131 and 863 he paid considerably more than the 1896 valuations of £19 10s and £5, but for lot 297 (valued at £15) slightly less.

Following Buchanan’s death in 1911, his manuscripts passed to his widow, who presented them to the Bodleian Library in 1939 and 194177. Wellcome also retained his manuscripts until his death in 1936, although some were sold in the 1940s. Two of Yates Thompson’s purchases (lots 580 and 903) remained in his collection until 1920. All these manuscripts therefore left the market for at least a generation, as did the manuscript sold by Leighton to McClean, which was included in his bequest to the Fitzwilliam Museum following his death in 1904. McClean bought another manuscript (lot 1118, a copy of the life and miracles of St Martin, £27) at Morris’ auction under the pseudonym « Money ». The pseudonym is suggestive, as the manuscript had been valued at just £10 in 1896. McClean acquired a third Morris manuscript (a Bible) in 1901 via Leighton, and these manuscripts were also bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam78. In 1912 M. R. James, by then the former director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, published a catalogue of the McClean manuscripts, noting the Morris provenance of the three books79.

As part of the continual changes to his collection, Yates Thompson sold the least expensive of his purchases (a copy of Lactantius, bought for £19) to the Boston Public Library for £20 in 190180. Sydney Cockerell arranged the sale, and also that of one of Morris’ manuscripts bought by Pickering & Chatto. The company made a better profit, as Boston paid £72 for the manuscript bought for £47 in 189881. Cockerell claimed this was « a considerable reduction on the price first asked », though the manuscript had been advertised for £60 in Pickering’s catalogue of the previous year82. This was the manuscript of which Pickering’s catalogue had suggested that the pen letters had appealed to Morris, and Cockerell went further, claiming that Morris had regarded it « with special affection on account of the extraordinary beauty of the penwork initials »83.

Some of the other buyers used pseudonyms at the 1898 sale and so are hard to identify. « Maine » was listed as the buyer for lot 124, an Antiphoner inscribed by its new owner George Dunn with the date January 189984. Among the other buyers of individual manuscripts were Morris’ executors. Cockerell purchased one volume, lot 792 « Le Testament Maistre Jehan de Mehun », for £29. Cockerell seems to have bought this volume for Yates Thompson, from whom he repurchased it in 1905 as part of a sustained effort to maintain contact with Morris’ books. The manuscript then remained in Cockerell’s collection until he began to disperse his library in the 1950s85. In 1898 Ellis was also listed as the buyer for one manuscript (lot 1061), although whether this was Frederick Ellis or his nephew Gilbert who was continuing the family bookselling business is unclear.

Although he had failed to buy Morris’ whole library, Fairfax Murray also obtained some manuscripts at and after the 1898 sale. He placed bids with Quaritch for three items, two printed books and a fifteenth-century manuscript Book of Sydrach (lot 1076), which he secured for £3086. Murray also acquired an Aristotle, and an Ambrosianum bought by Quaritch (lots 134, 120), and he gave all three manuscripts to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1904. In addition, Murray acquired the Steinfeld Missal, bought by Quaritch in 1898 (lot 1070), which was part of a selection of at least forty manuscripts that he sold to Charles Dyson Perrins in 1905 and 190687.

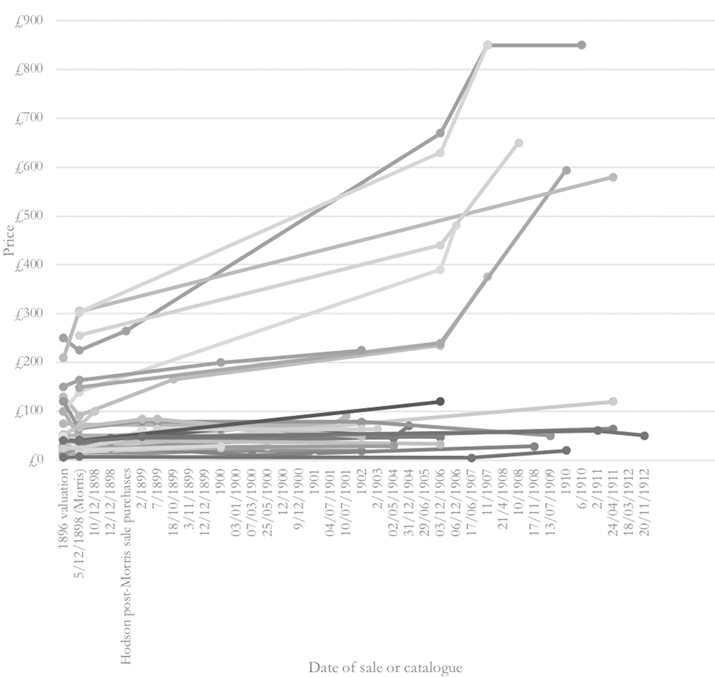

About half the manuscripts in the 1896 valuation did not appear on the market between the 1898 sale and 1914. At or shortly after the 1898 sale, eighteen manuscripts went into the collections of Wellcome, Yates Thompson, Buchanan, and Stainton where they remained until at least 1914. An additional two manuscripts went to the Boston Public Library in 1901. Three manuscripts were acquired by McClean and went to the Fitzwilliam Museum following his death, and a further three were given to the Fitzwilliam by Fairfax Murray in 1904. In addition, Bennett sold thirty manuscripts to Morgan by private sale. However, there is evidence for thirty-eight of the remaining manuscripts from the 1896 inventory on the market again before 1914, sometimes changing hands multiple times [ill. 3]. The fate of these manuscripts demonstrates the tight-knit nature of the community interested in illuminated manuscripts in this period, as some of these manuscripts were traded by Quaritch and Leighton and were bought by those who had purchased manuscripts in 1898.

Ill. 3. Prices asked or paid for William Morris’ manuscripts on the market 1898-1914.

Although the acquisition of many of Morris’ manuscripts by private collectors by 1900 took them off the open market for a generation or more, the death of Alfred Higgins in 1903 brought his collection, including two items from Morris’ sale, back to Sotheby’s on 2 May 1904. Higgins’ sale was much smaller than Morris’ had been, containing about 250 lots, of which eighteen were medieval western manuscripts. Morris’ ownership was noted in the catalogue entries for the Glossed Gospels (Higgins lot 62) and the Statutes (Higgins lot 225). Both manuscripts had been acquired from Leighton in 1898, for £25 and £45 respectively. At Higgins’ sale Leighton reacquired the Statutes for £45 and made quick and substantial profit by selling the manuscript on to Perrins two weeks later for £7088. The manuscript then remained in Perrins’ collection until his death in 1958. The Gospels were bought by Cockerell for £29, as he built his collection of items once owned by Morris. Both manuscripts therefore left the market for half a century.

Cockerell bought another of Morris’ manuscripts, a copy of Peter Comestor’s Historia Scholastica, when it appeared at auction in June 1905, although this appears to have been on behalf of Cambridge University Library89. The manuscript was sold anonymously and without reference to its provenance. It had been valued at £18 10s in 1896, sold for £16 in 1898 (lot 371), but in 1905 fetched just £10.

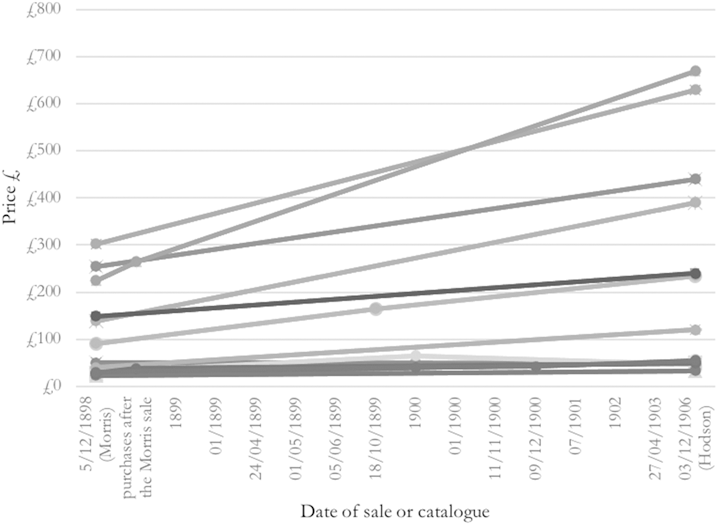

In December 1906, a decade after the valuation of Morris’ library, a second group of Morris’ manuscripts returned to Sotheby’s. Laurence Hodson was a devotee of William Morris. He had employed Morris & Co. to design the interiors of his house, Compton Hall, near Wolverhampton, and Morris named a wallpaper design Compton. Hodson had placed bids for nine manuscripts through Quaritch at the sale of Morris’ library in 1898, obtaining seven for a total of £1,019 plus commission. He obtained two more Morris manuscripts, probably around the time of the sale, from Leighton for a further £303, and subsequently acquired another two (both originally bought by Pickering & Chatto) through them; a Pontificale (lot 696) in 1900 for £42 and a Bible (lot 86) in October 1899 for £165. He also purchased one of the Bibles (lot 35) offered for sale by Pickering & Chatto in 1900. Hodson continued to acquire not only Morris’ medieval manuscripts, but also volumes from the Kelmscott press and Morris’ autographs. He inserted into the manuscripts a bookplate closely modelled on Morris’ own. In December 1906, in financial difficulty, Hodson sold his library at Sotheby’s. The importance of Morris for the collection was suggested by the title given to the sale : Catalogue of the Valuable Library of Ancient Manuscripts and Valuable and Rare Printed Books, including Several Original Holograph Manuscripts of the Publications of William Morris; the Kelmscott Press Books on Vellum; the Essex & Other Art Presses, &c. In Hodson’s sale thirteen medieval manuscripts were identified as having come from Morris’ library and the prices of five from the 1898 sale were included. These (Hodson’s lots 45, 46, 50, 275, 617) were, unsurprisingly, five of the six most expensive manuscripts that featured in both sales. As in 1898, the press coverage focused on high prices and increasing value. Yet not all the manuscripts from Morris’ collection in Hodson’s sale had increased in value [ill. 4]. A volume of Augustine’s sermons (Hodson’s lot 28) sold for £48, having fetched £50 in 1898. Other manuscripts brought relatively modest increases in prices. While four of the five Bibles achieved 2-3 times their 1898 prices, Hodson’s lot 49 (sold in 1898 for £30) saw a smaller increase to £47. Similarly a Cicero sold for £27 in 1898 (having been valued at £20 in 1896) was now bought for £50, and a glossed volume of the Pauline Epistles sold for £23 in 1898 now fetched £33. Both manuscripts were bought by Cockerell, who acquired another of Morris’ manuscripts, known as the Golden Psalter, from Hodson in a private sale in 190990. Cockerell also bought a thirteenth-century Old Testament that had been owned by Morris and Hodson from Quaritch immediately after the Hodson sale. At Hodson’s sale it had sold for £390, but Cockerell paid £480, noting in his diary that it was « all the money I have in the world »91.

Ill. 4. Prices paid (or asked) for manuscripts that appeared in both William Morris’ 1898 sale and Laurence Hodson’s sale 1898-1906.

The prices raised for the Morris manuscripts sold at the Hodson sale show a notable divergence between the high and low values of 1898. The six manuscripts that sold for £90 or more in 1898 in 1906 all sold for considerably higher prices (on average 230 % of their 1898 value). With one notable exception (a Bible that sold for £40 and £120), manuscripts that had sold for £50 or less saw their prices increase less dramatically, and in one case not at all, with the seven manuscripts that sold for £50 or less in 1898 achieving an average of 178 % of their 1898 value. This trend is also observable in the larger set of Morris’ manuscripts as they were sold in this period [ill. 3]. However, in this the Morris manuscripts do not seem to have been exceptional. There is no benchmark for the other thirty-six manuscripts sold by Hodson in 1906 and the four highest prices paid for manuscripts were all for Morris’ books. Yet where previous sale prices and valuations can be identified the trends seem to be broadly similar to those for items from Morris’ collection, and these continue up to 1914, albeit with the suggestion of a decline in some prices after 1910 [ill. 5].

Ill. 5. Price data for manuscripts owned by Hodson 1898-1914.

In 1908 Perrins acquired one of the Morris Bibles from the Hodson sale via Quaritch92. Together with the volume of Statutes purchased from Leighton after the Higgins sale and the Steinfeld Missal bought from Fairfax Murray this brought Perrins’ holdings of manuscripts owned by Morris to three. However, in June 1907 Perrins had sold a volume of the works of Ambrose (and possibly also a Bible) that had been in Morris’ collection93. The sale was anonymous and was probably an attempt to reduce the size of his library as part of an effort towards organization that included recruiting Cockerell in April 1907 to catalogue his manuscripts94. At the outset of his collecting Perrins had paid high prices for manuscripts, and many of the items sold in 1907 fetched less than he had paid for them. The prices may not have been helped by the idea of the sale as containing books being rejected from a collection, carrying a stigma of « second class » items. The volume of Ambrose’s works had been valued in 1896 at £5 10s and was bought by Tregaskis in 1898 for £6 15s. However when Perrins sold it in 1907 it was purchased by the dealer Bertram Dobell for just £4 10s. The manuscript is next sighted in Munich, offered for sale by Ludwig Rosenthal for 400 Marks in 1910, with Morris’ provenance noted. Perrins continued collecting and acquired the manuscript in a twelfth-century binding that had been one of the stars of the 1898 sale at the Yates Thompson sale of 1920. He paid £740 for the manuscript that Yates Thompson had bought for £180 in 1898, which had cost Morris just £13 in 1896.

The relationship between Cockerell and Perrins provided the foundation for a major exhibition of manuscripts at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in London in 1908. The items for exhibition were largely selected by Cockerell, and 50 of Perrins’ books, including the Steinfeld Missal and the Bible from Hodson’s collection, formed its core. Cockerell’s continuing debt to his time with Morris was reflected in his reference to Morris in the introduction to the exhibition’s catalogue, where he wrote of Morris and John Ruskin: « These two great writers and collectors have done more than any other Englishmen to increase the love of Mediaeval Art, and a glance at the books that they loved so well will show how fine was their judgement »95. Nineteen manuscripts from Morris’ collection featured in the exhibition (although three of these were volumes of the same Bible). In addition to the two provided by Perrins, twelve were lent by J. P. Morgan, echoing the importance of Morris’ provenance indicated in James’ catalogue of 1906, but skewing the representation of Morgan’s collection as only six other items were included96. The other lenders of manuscripts once owned by Morris were Bruce Ingram and Cockerell himself.

While 1908 saw the display of some of the Morris manuscripts in Morgan’s collection in London, two more manuscripts from Morris’ collection appeared at auction in New York. The first was a copy of Aristotle’s Ethicorum. This had been sold to Leighton in 1898 for Butler (lot 71) for £7 5s, having been valued at £15 in 1896. In 1908 it was sold as part of the library of Perry A. Preston and raised $85 (approximately £17)97. In November, the glossed copy of the Books of Kings that had featured in Edelheim’s sale in 1900 reappeared on the market, now as part of the library of Henry W. Poor, whose business was failing. Poor made a good profit on this manuscript, which having sold for $47.50 in 1900 now fetched $14198. At this sale Morris’ name was once again mentioned in connection with the volume.

Three more manuscripts from Morris’ collection appeared at auction in New York in 1911, following the death of Robert Hoe. These manuscripts had also been included in the catalogue of his collection finished and published after Hoe’s death in 1909, which listed 152 manuscripts made before 160099. In all three cases the manuscripts sold for much larger sums than they had fetched in 1898. The copy of Josephus that had attracted comment when it sold for £305 in 1898 now raised $2,900 (approximately £580)100. A work attributed to Onasander (lot 694) that was sold for £23 in 1898 raised $600 (£120) and went to the Morgan Library (where it is now M. 449), and the volume of Cicero that had sold for £32 in 1898 (lot 365) fetched $320 (£64). The latter is now in the Huntington Library, HM 1031. In this instance, the most expensive item in 1898 had the smallest price increase in percentage terms, but all three items benefitted from their inclusion in a major sale that attracted buyers from Europe.

The end of the first decade of the twentieth century also provides more evidence of Morris’ manuscripts in continental Europe. In 1898 two manuscripts (lots 912, 1190) had been bought by the Berlin-based dealer Martin Breslauer for £4 and £8 15s. One of these manuscripts, Alexander de Villa Dei’s Doctrinale, was listed in Breslauer’s catalogue in 1901. Another manuscript (lot 306), a Boethius, was bought in 1898 by Quaritch for Otto Harrassowitz of Leipzig and was quickly transferred to the Berlin Royal Library. In addition to the volumes acquired by the Royal Library of Belgium in 1900, de Marinis (based in Florence) by 1909, and Ludwig Rosenthal (brother of Jacques and also based in Munich), in 1910 Leo Olschki (based in Florence) included one of Morris’ manuscripts in his catalogue. This was a life of St Catherine of Siena, bought by Quaritch at the Hodson sale, which Olschki subsequently sold to Henry Walters (now Baltimore, Walters Art Museum W.350). By the time of the start of the First World War, therefore, at least forty-four of Morris’ manuscripts had left Britain. Thirty-seven or more had travelled to America, and at least seven to continental Europe, although one of these (that listed as sold in de Marinis’ 1909 catalogue) returned to Britain. Without Morgan’s purchase of the Bennett collection, therefore, the numbers of manuscripts departing for Europe and America would have been roughly equal.

Although the London Daily News identified Morris’ remarkable qualities when part of his library came up for sale in 1898, the fate of his manuscripts was not so exceptional. Indeed, the purchase of the library by Bennett and the subsequent sale of those books he did not want found a parallel in Yates Thompson’s treatment of the Ashburnham Appendix. The first generation of buyers at the Morris library sale included people who had known or known of Morris, notably Cockerell, Vigers and Hodson, but also dealers and established collectors. The dispersal of the collections into which Morris’ manuscripts were incorporated was then determined by the buyers’ fortunes and longevity. With the exception of Cockerell, who continued to add Morris’ manuscripts to his collection, the books became increasingly scattered. In part thanks to the efforts of Cockerell, but also due to the institutional knowledge of firms like Quaritch and Leighton and the presence of his bookplates, Morris’ name continued to be attached to many, though not all, of the manuscripts as they entered other collections, were exhibited, and returned to the market. The London Daily News, echoed by Henry Wheatley, had therefore captured something profound, that the celebrity of the owner might be associated with the items he had chosen to collect, adding to their value in way that was never precisely defined. The role that Morris’ name played in increasing the economic value of the books remains unclear. In part, this is because many of the most expensive books were transferred from Bennett to Morgan en bloc, but those manuscripts auctioned in 1898 did not on the whole raise more than Morris had paid for them. As books passed through multiple collections identifying the impact of their association with any one collector becomes more difficult. Morris’ name continues to attract more recognition than Higgins’ or Hodson’s, but to those interested in manuscripts Yates Thompson and Perrins may be equally familiar. Strikingly the Morris provenance does not seem to have helped the manuscripts that sold for less than about £90 in 1898, almost all of which continued to be sold for prices around those realised at Morris’ sale until 1914. However, books that sold for higher prices, roughly the top 10 %, significantly increased in value, marking the beginning of a trend that would see record prices in the 1920s. Those prices were, in part, fuelled by the international nature of the manuscript trade. Despite concerns about the rise of an American market in 1898, very few manuscripts left Britain immediately after Morris’ sale. By 1914, however, at least a third of his collection had been sent abroad, including the thirty volumes bought by Morgan. Although Morris formed his collection in order to better understand the design of books, therefore, its fate demonstrates the importance of a small group of collectors and dealers in the early twentieth century in determining the subsequent destinations of many of these volumes as well as their perceived economic value.

Appendix : Manuscripts sold at the sale of William Morris’ library, 5 December 1898101.

| Lot number | Price | Buyer | Current location (year of acquisition) |

| 33 | £73 | Bruce | Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS McClean 12 (1904) |

| 34 | £24 10s | Leighton | Philadelphia, Free Library, Lewis E 036 |

| 35 | £30 | Pickering | Cambridge University Library, Add. MS 6159 (1918) |

| 36 | £16 10s | Heppinstal | |

| 37 | £40 | Pickering | |

| 38 | £18 | Heppinstal | London, Society of Antiquaries MS 956 (1994) |

| 52 | £36 | Ridges | |

| 71 | £7 5s | Leighton | Harvard, Houghton Library MS Lat. 266 (1908) |

| 78 | £25 10s | Leighton | Harvard, Houghton Library MS Typ. 289 (1967/1984) |

| 86 | £91 | Pickering | |

| 87 | £36 | Pickering | Ohio University, BS75 1200x |

| 88 | £61 | Pickering | |

| 118 | £6 15s | Tregaskis | |

| 120 | £36 | Quartich | Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS CFM 9 (1904) |

| 124 | £18 5s | Maine | British Library Egerton MS 2977 (1917) |

| 125 | £9 5s | Littlewood | |

| 126 | £40 | Bain | |

| 131 | £25 | Buchanan | Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Buchanan c. 1 (1941) |

| 134 | £26 | Quaritch | Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS CFM 14 (1904) |

| 148 | £50 | Quaritch (for Hodson) | Harvard, Houghton Library MS Typ 703 (1984) |

| 167 | £31 | Quaritch | New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M.968 (1975) |

| 168 | £139 | Quaritch (for Hodson) | Los Angeles, J. P. Getty Museum, MS Ludwig I.8 (1983) |

| 169 | £47 | Pickering | Boston Public Library MS f. Med 1 (1901) |

| 170 | £302 | Quaritch (for Hodson) | Wormsley Library |

| 171 | £77 | Pickering | |

| 172 | £20 | Slinder | |

| 297 | £13 | Buchanan | Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Buchanan e. 15 (1941) |

| 306 | £61 | Quaritch (for Harrossowitz) | Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, MS Lat. Fol. 601 (1898) |

| 345 | £149 | Quaritch (for Hodson) | Baltimore, Walters Art Museum W. 350 |

| 357 | £27 | Quaritch (for Hodson) | New Haven, Yale University, Beinecke Library MS 93 (1945) |

| 358 | £81 | Waring | |

| 365 | £32 | Stevens | San Marino, Huntington Library HM 1031 |

| 371 | £16 | Heppinstal | Cambridge University Library MS Add. 6760 |

| 387 | £38 | Quaritch | British Library, Add. MS 38644 (1912) |

| 418 | £5 10s | Leighton | |

| 437 | £40 | Edwards | Oxford, Keble College MS 77 |

| 438 | £6 15s | Heppinstal | Bloomington, Lilly Library, Poole 264 |

| 439 | £10 10s | Wilton (Wellcome) | Koninklijke Bibliotheek Netherlands (KW79K30) (2012) |

| 470 | £27 10s | Leighton | Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, MS. Lat. Qu. 761-5 (1916/17) |

| 480 | £11 | Waring | |

| 487 | £49 | Quaritch | Poitiers, Bibliothèque municipale MS 1106 |

| 513 | £23 | Quaritch | |

| 520 | £10 10s | Leighton | |

| 522 | £20 | Ridge | Worcester Cathedral MS Q. 107 |

| 558 | £255 | Quaritch (for Hodson) | Baltimore, Walters Art Museum W.133 |

| 560 | £24 | Quaritch | Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Lat. Th. B. 4 (1942) |

| 561 | £67 | Quaritch | Liverpool University Library MS F. 4. 20 |

| 563 | £65 | Quaritch | Huis Bergh Castle 0217 (1935) |

| 580 | £180 | Yates Thompson | Winchester Cathedral MS 20 (1948) |

| 587 | £5 5s | Leighton | Williamstown, Williams College MS XIII |

| 662 | £9 15s | Wilton (Wellcome) | |

| 694 | £23 | Quaritch (for Hoe) | New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M.449 (1911) |

| 696 | £30 | Deacon | New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M.976 (1977) |

| 732 | £305 | Quaritch | New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M.533 and 534 |

| 736 | £14 14s | Wilton (Wellcome) | Yale University, Lilliam Goldman Law Library Rare Flat 11-0030 |

| 745 | £19 | Yates Thompson | Boston Public Library MS f. Med. 14 (1901) |

| 792 | £29 | Cockerell | Harvard, Houghton Library MS Typ 749 (1984) |

| 798 | £19 | Heppinstal | Brussels, Royal Library MS II 2663 (1900) |

| 815 | £15 | Wilton (Wellcome) | British Library, Egerton MS 3271 (1943) |

| 862 | £22 | Wilton (Wellcome) | Indiana, Unversity of Notre Dame, MS Lat. c. 6 (before 1962) |

| 863 | £12 12s | Buchanan | Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Buchanan d. 4 (1941) |

| 866 | £97 | Quaritch (for Hodson) | British Library, Add. MS 81084 (2005) |

| 867 | £45 | Wilton (Wellcome) | |

| 903 | £350 | Yates Thompson | Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales MS 15536E (1951) |

| 904 | £30 | Wilton (Wellcome) | |

| 912 | £4 | Breslauer | Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, MS Lat. Fol. 600 |

| 930 | £7 | Wilton (Wellcome) | London, Wellcome Collection MS 591 |

| 932 | £11 | Wilton (Wellcome) | |

| 972 | £85 | Leighton | Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame MS Lat. e. 4 (1977/8) |

| 988 | £69 | Leighton | Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS McClean 179 (1904) |

| 1023 | £11 10s | Wilton (Wellcome) | Harvard, Houghton Library MS Lat 426 |

| 1061 | £1 14s | Ellis | |

| 1070 | £95 | Quaritch | Los Angeles, J. P. Getty Museum, MS Ludwig V 4 (1983) |

| 1076 | £30 | Quaritch (for Fairfax Murray) | Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS CFM 16 (1904) |

| 1118 | £27 | Money (McClean) | Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS McClean 118 (1904) |

| 1137 | £40 | Leighton | |

| 1155 | £225 | Leighton | Los Angeles, J. P. Getty Museum, MS Ludwig I 4 (1983) |

| 1190 | £8 15s | Breslauer | Yale University, Beinecke Library Marston MS 64 |

| 1194 | £164 | Heppinstal | San Marino, Huntington Library HM 1036 (1918) |

____________

1 « The William Morris Library », London Daily News, 6.12.1898.

2 See Graily HEWITT, The Illuminated Manuscripts of William Morris, 1934 ; Paul NEEDHAM (ed.), William Morris and the Art of the Book, Oxford, University Press, 1976 ; Julian TRUEHERZ, « The Pre-Raphaelites and Mediaeval Illuminated Manuscripts », in Pre-Raphaelite Papers, ed. L. Parris, London, Tate Gallery, 1984, p. 153-169 ; William S. PETERSON, The Kelmscott Press: A History of William Morris’s Typographical Adventure, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1991.

3 Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector » in Paul Needham (ed.), William Morris and the Art of the Book, op. cit. [note 2], p. 21-47 ; Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris’s “Ancient Books” at Sale », in Under the Hammer: Book Auctions Since the Seventeenth Century, ed. R. Myers, M. Harris, G. Mandelbrote, New Castle DE & London, Oak Knoll, 2001, p. 173-208 ; Michaela BRAESEL, William Morris und die Buchmalerei, Cologne, Böhlau, 2019. Braesel’s study includes an appendix with details of manuscripts associated with Morris. A similar endeavour is documented at https://williammorrislibrary.wordpress.com/ [consulted 27 August 2020].

4 Notably in Burlington Fine Arts Club: Exhibition of Illuminated Manuscripts, London, 1908 ; see also Wilfrid BLUNT, Sydney Carlyle Cockerell, friend of Ruskin and William Morris and Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, London, Hamilton, 1964, p. 58-75 ; Richard A. LINENTHAL, « Sydney Cockerell: Bookseller in all but name », Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 13, 2007, p. 363-386 ; Stella PANAYOTOVA, “I turned it into a palace”: Sydney Cockerell and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, 2008.

5 James TREGASKIS, « Forewords », The Caxton Head Catalogue No. 500, 18.11.1901.

6 Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector », art. cit. [note 3], p. 23-31 ; Norman KELVIN (ed.), The Collected Letters of William Morris, Princeton, University Press, 1996, 4 vols.

7 Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector », art. cit. [note 3], p. 25 ; Michaela BRAESEL, William Morris…, op. cit. [note 3], p. 472-3 ; the catalogue of c. 1876 is now Paul Mellon Collection, Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven ; British Library, RP 1221.

8 Michaela BRAESEL, William Morris…, op. cit. [note 3], p. 473.

9 Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector », art. cit. [note 3], p. 29-33 ; Michaela BRAESEL, William Morris, op. cit. [note 3], p. 474-475. The catalogue is now Dallas, Southern Methodist University, Bridwell library ; British Library, Microfilm RP 1355i.

10 « The William Morris Library », The Times, 3.11.1898.

11 Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector », art. cit. [note 3], p. 34 ; Norman KELVIN, « Bernard Quaritch and William Morris », The Book Collector, 1997, p. 118-120 ; Richard A. LINENTHAL, « Sydney Cockerell… », art. cit. [note 4], p. 366.

12 Bernard Quartich Ltd. Archive, « Commission Book Mar. 1895-Apr. 1899 », Morris bid for lots 358, 28, and 555.

13 Norman KELVIN, Collected Letters…, op. cit. [note 6], IV, p. 261.

14 Ibidem, IV, p. xxx ; Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris’s “Ancient Books”… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 176.

15 Norman KELVIN, Collected Letters…, op. cit. [note 6], IV, p. 371.

16 « The Poet as Printer: An Interview with Mr. William Morris », The Pall Mall Gazette, 12.11.1891 ; see also « The Paradoxical William Morris », Dundee Evening Telegraph, 24.7.1899.

17 Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector », art. cit. [note 3], p. 44 ; Paul NEEDHAM, « Ancient Books… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 176.

18 San Marino, Huntington Library, Sanford & Helen Berger Collection, Box 1, MOR 9. A page is reproduced as plate V in Paul NEEDHAM (ed.), William Morris and the Art of the Book, op. cit. [note 2]; see also Paul NEEDHAM, « Ancient Books… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 176-177. The document lists 117 numbered items, but some of these are identified as duplicates.

19 Norman KELVIN, Collected Letters…, op. cit. [note 6], IV, p. 401 ; see also Paul NEEDHAM (ed.), William Morris and the Art of the Book, op. cit. [note 2], p. 99.

20 Norman KELVIN, Collected Letters…, op. cit. [note 6], IV, p. 401-404 ; Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector », art. cit. [note 3], p. 44 ; see also Sydney. C. COCKERELL, « Diary for 1896 », British Library Add. MS 52633, fol. 71v.

21 Robert STEELE (ed.), Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-Lore and Myth of the Middle Age, London, Stock, 1893.

22 Norman KELVIN, Collected Letters…, op. cit. [note 6], IV, p. 223-4.

23 Sydney C. COCKERELL, « Diary for 1896 », op. cit. [note 20], fol. 64.

24 « Mr. William Morris’s Will », London Evening Standard, 17.12.1896 ; Paul NEEDHAM, « Ancient Books… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 177.

25 Sydney C. COCKERELL, « Diary for 1896 », op. cit. [note 20], fol. 72 ; Sydney C. COCKERELL, « Diary for 1897 », British Library Add. MS 52634, fol. 12 ; Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector », art. cit. [note 3], p. 44 ; Paul NEEDHAM, « Ancient Books… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 178-181. Due to the global pandemic in 2020 I have been unable to consult relevant documentation in the Morgan Library.

26 See Sydney C. COCKERELL, « Diary for 1897 », op. cit. [note 25].

27 Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris: Book Collector », art. cit. [note 3], p. 45.

28 Norman KELVIN, Collected Letters…, op. cit. [note 6], IV, p. 401 ; Paul NEEDHAM, « William Morris’s “Ancient Books”… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 183-184.

29 Henry B. WHEATLEY, Prices of Books: An Inquiry into the Changes in the Price of Books which have Occurred in England at Different Periods, London, Allen, 1898, p. 73.

30 Sydney COCKERELL, « Diary for 1899 », British Library Add. MS 52636, fol. 65v.

31 A Catalogue of the Early Printed Books and Illuminated Manuscripts Collected by Richard Bennett, n. p., 1900 ; see also Richard W. PFAFF, Montague Rhodes James, London, Scolar Press, 1980, p. 194.

32 Catalogue of Manuscripts and Early Printed Books from the Libraries of William Morris, Richard Bennett, Bertram Fourth Earl of Ashburnham, and other sources now forming portion of the library of J. Pierpont Morgan, London, Chiswick Press, 1906.

33 A Catalogue […] Collected by Richard Bennett, op. cit. n. 31, catalogue numbers 561, 562, 566, 567, 569, 570, 571, 580, 584, 585, 622, 633, 635, 642, 646, 647, 648, 649, 650, 651, 653, 655, 659, 660, 661, 664, can be identified as manuscripts from Morris.

34 Catalogue of a portion of the valuable collection of Manuscripts, Early Printed Books, &c. of the late William Morris, Of Kelmscott House, Hammersmith, Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, 5.12.1898.

35 « The William Morris Library », The Times, 3.11.1898.

36 See also Paul NEEDHAM, « Ancient Books… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 185-186.

37 These are now New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M.154 and M.186.

38 The Sherbrooke Missal is now Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales, MS 15536E.

39 Paul NEEDHAM, « Ancient Books… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 177.

40 « London Letter », Western Daily Press, 12.12.1898.

41 Sydney C. COCKERELL, « Diary for 1898 », British Library Add. MS 52635, fol. 60v.

42 The article appeared in Truth, 21.4.1898 ; and was later reprinted in other papers.

43 « Sale of Books and Manuscripts », The Times, 1.4.1898, p. 11.

44 This is now New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M. 533 & 534.

45 Catalogue of a portion of the valuable collection of Manuscripts, lot 732 ; Bernard Quaritch Ltd. Archive, « Commission Book Mar. 1895 – Apr. 1899 ».

46 Now Winchester Cathedral MS 20.

47 Now Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales MS 15536E.

48 On Yates Thompson see Christopher DE HAMEL, « Was Henry Yates Thompson a Gentleman? », in Property of a Gentleman: The Formation, Organisation and Dispersal of the Private Library 1620-1920, ed. R. Myers and M. Harris, Winchester, St. Paul’s Bibliographies, 1991, p. 77-89.

49 Frank HERRMANN, « The Role of the Auction Houses », in Out of Print and Into Profit : a history of the rare and secondhand book trade in Britain in the twentieth century, ed. Giles Madelbrote, London, British Library, 2006, p. 13-21.

50 « Book and Curio Sales », Glasgow Herald, 10.12.1898.

51 For Wellcome see: Helen TURNER, Henry Wellcome: The Man, His Collection and His Legacy, London, The Wellcome Trust, and Heinemann, 1980 ; Robert R. JAMES, Henry Wellcome, London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1994.

52 Bernard Quaritch Ltd. Archive, « Commission Book Mar. 1895 – Apr. 1899 ».

53 Luther S. LIVINGSTON, American Book-Prices Current, New York, Dodd, Mead & Co., 1900, p. 513.

54 See Angus O’NEILL, « Prices and Exchange Rates », in Out of Print and Into Profit…, op. cit. [note 49], p. 333-5.

55 See also Paul NEEDHAM, « Ancient Books… », art. cit. [note 3], p. 197.

56 « The Exportation of Rare Books to America: A Famous Library Sold », The Times, 7.7.1902.

57 Norman KELVIN, Collected Letters…, op. cit. [note 6], IV, p. 364, 366, 370-371.

58 In the 1896 inventory these are items 12, 14-16, 18-25, which were sold as lots 33-8, 86-8, 168-70. It is impossible to reconcile all the individual entries in the list and sale catalogue with certainty. Lot 170 is now in the Wormsley Library.

59 « Sale of the Morris Library », London Evening Standard, 7.12.1898.

60 Lots 387, 487, 560, 561 and 563 in the 1898 sale.

61 Catalogue of Old and Rare Books ; and a Collection of Valuable Old Bindings, with Coloured and Other Facsimiles, for sale, with prices affixed, by Pickering & Chatto, 1900, cat. nos. 1033, 1034.

62 Ibid., cat. nos. 1031, 1066, 1097a, 1101, 1121, 3377.

63 Ibid., cat. no. 1031, p. 111.

64 Ibid., cat. no. 1034, p. 111.

65 William P. STONEMAN, « “Various Employed”: The Pre-Fitzwilliam Career of Sydney Carlyle Cockerell », Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 13, 2007, p. 355.

66 William MORRIS, « Some Notes on the Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages », The Magazine of Art, 17, 1893, p. 83-88.

67 No. 190 A Catalogue of Superbly Illuminated and Decorated Mediaeval Manuscripts, Rare and Valuable Books Relating to the Fine Arts, Sports and General Literature offered at the net prices affixed, by Bernard Quaritch, 1899, nos. 3, 12, and 13.

68 The manuscript is now in the Library of Liverpool University, MS F. 4. 20 ; see N. R. Ker, Medieval Manuscripts in British Libraries, 5 vols, Oxford, University Press, 1969-2002, III, p. 315.

69 This manuscript is now British Library, Add. MS 38644.

70 Manuscrits – Autographes, riche collection d’ouvrages de musique, incunables et livres rares mis en vent a la librairie ancienne T. de Marinis & C., Florence, 1909, no. 231, p. 74 ; now Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Lat. Th. B 4.

71 British Library, Add. MS 45170.

72 Now Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS McClean 179.

73 British Library, Add. MS 45161.

74 British Library, Add. MS 45162.

75 See also Wellcome Collection, Accessions book 1, WAHMM/LI/Acc/1, entry for Morris sale with total £1,950 15s 6d.

76 Wellcome Collection, MS 591.

77 The manuscripts are now Oxford, Bodleian Library, MSS Buchanan c. 1, d. 4 and e. 15 ; see P. Kidd, Medieval Manuscripts from the collection of T.R. Buchanan in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (Oxford, 2001).

78 British Library, Add. MS 45163.

79 Montague R. JAMES, A Descriptive Catalogue of the McClean Collection of Manuscripts in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, University Press, 1912. The Morris manuscripts are nos. 12, 118, 179.

80 William P. STONEMAN, « Various Employed… », art. cit. [note 65], p. 355 ; these manuscripts are now Boston Public Library MSS f. Med. 1 and f. Med. 14.

81 William P. STONEMAN, « Various Employed… », art. cit. [note 65], p. 355.

82 Ibidem ; see also Catalogue of Old and Rare Books […], op. cit. n. 61.

83 William P. STONEMAN, « Various Employed… », art. cit. [note 65], p. 355.

84 Now British Library MS Egerton 2977.

85 The manuscript is now Harvard University, Houghton Library MS Typ 749 ; see William P. STONEMAN, « Various Employed… », art. cit. [note 65], p. 356.

86 Bernard Quaritch Ltd. Archive, « Commission Book Mar. 1895 – Apr. 1899 ».

87 For the manuscripts in the Fitzwilliam Museum see Francis WORMALD and Phyllis M. GILES, « A Handlist of the Additional Manuscripts in the Fitzwilliam Museum », Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 1.3, 1951, p. 197-207 ; for the Perrins purchases see Laura CLEAVER, « Charles William Dyson Perrins as a Collector of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts c. 1900-1920 », Perspectives Médiévales (2020) https://journals.openedition.org/peme/19776 [accessed 7.9.2020]. The Missal is now Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, MS Ludwig V 4.

88 British Library, Add. MSS 45164 ; 45172.

89 Catalogue of Valuable Books and Manuscripts […], Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, 29.6.1905, lot 583.

90 The Psalter was lot 866 in 1898 ; Norman KELVIN, Collected Letters…, op. cit. [note 6], p. 381.

91 Sydney C. COCKERELL, « Diary for 1906 », British Library, Add. MS 52643, fol. 64.

92 George WARNER, Descriptive Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts in the Library of C. W. Dyson Perrins 2 vols., Oxford, University Press, 1920, cat. 29.

93 Catalogue of a Selected Portion of the Choice and Valuable Library of Ancient Manuscripts and Early Printed Books, the Property of a Gentleman, Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, 17.6.1907.

94 See Laura CLEAVER, « Dyson Perrins… », art. cit. [note 87].

95 Burlington Fine Arts Club, op. cit. n. 4, p. xxviii.

96 Burlington Fine Arts Club, op. cit. n. 4, cat. nos. 36, 47, 52, 63, 75, 80, 123, 124, 125, 129, 131, 137.

97 Luther S. LIVINGSTON, Amerivan Book-Prices Current, New York, Dodd, Mead and Company, 1908, p. 615 ; now Harvard University, Houghton Library MS Lat. 266.

98 Luther S. LIVINGSTON, Amerivan Book-Prices Current, New York, Dodd, Mead and Company, 1909, p. 877 ; now New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M.968.

99 Carolyn SHIPMAN, A Catalogue of Manuscripts Comprising a Portion of the Library of Robert Hoe, New York, 1909.

100 Now New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M.533 & 534.

101 See also Michaela BRAESEL, William Morris…, op. cit. [note 3], p. 607-615.